The exhibition Parasitic Symbiosis is a continuation of the artistic collaboration between Pille-Riin Jaik and Miriam Esther Meyer. Lately extensively commercialised and overused, the idea of collaboration has migrated to marketing and communication strategies, but its initial momentum was carved out along the way. Jaik and Meyer otherwise critically approach fundamental togetherness and supportiveness within it. They acknowledge and demonstrate co-dependence in artistic practice, and speculate on a potentially warm and inclusive fellowship built on it, to thus confront the historic modernist male White Cube.

Parasitic Symbiosis fills the space of the Hobusepea Gallery with loosely distributed irregular organic shapes. The double installation So, I Weed and So, I Weed & I Weed by Pille-Riin Jaik spreads erratically across the floor, entwines around the regular structures and the stairs, and hangs down from the window. Like natural invasive weeds, these paper plants occupy the corners, sit on edges, fit between and lurk beneath. The long history of weed control reflects man’s desire to suppress and govern nature. In this case, the issue of environmental domination extends to social hierarchies, because Jaik’s vegetation is made up of archive files from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, tracing the history of the exclusion of local women from studying and teaching art.

The very artistic gesture of cutting and folding flowers from bureaucratic documents, instead of studying them and putting them out on display, might appear passive and romantic, but it is far from it. I think the way Jaik deals with this intentionally polarises the context and confronts the logic of the male gaze. She adapts the stories of women who were denied an art education into the new narrative, and respects their voices and struggles like a root that nourishes her own practice. A patch of grass or a dandelion demands fine manual work, which means long and carful contact with the archive, tactile connection, and the somatic experience of these notes and letters. But the unreadable paper plants become agents of female art kinship and co-responsibility, while the reference to weed points to the relationship between patriarchy and the environmental crisis. The protest appears to be soft and poetic, but it is sprouting up unnoticed, burgeoning right under our feet, and invading secluded areas, with the security guards unaware of it. A different tactic.

The very artistic gesture of cutting and folding flowers from bureaucratic documents, instead of studying them and putting them out on display, might appear passive and romantic, but it is far from it. I think the way Jaik deals with this intentionally polarises the context and confronts the logic of the male gaze. She adapts the stories of women who were denied an art education into the new narrative, and respects their voices and struggles like a root that nourishes her own practice. A patch of grass or a dandelion demands fine manual work, which means long and carful contact with the archive, tactile connection, and the somatic experience of these notes and letters. But the unreadable paper plants become agents of female art kinship and co-responsibility, while the reference to weed points to the relationship between patriarchy and the environmental crisis. The protest appears to be soft and poetic, but it is sprouting up unnoticed, burgeoning right under our feet, and invading secluded areas, with the security guards unaware of it. A different tactic.

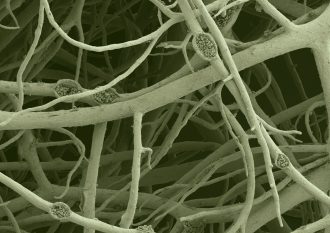

Surrounded by flourishing weeds, Dependency Action Liberation is a series of abstract plant paintings sealed in latex. Miriam Esther Meyer’s pieces are based on performative drawing, which in this context means that the work process correlates with the pace of her collaborator. Meanwhile, as Jaik was sculpting the flowers, Meyer was drawing, and had to keep going until her partner finished the work. Each break, either a short break or an overnight one, left a corresponding gap, a void. By delegating the timeframe, the artist approaches the challenge of an open end, and questions the very notion of the completeness of an artwork. Smooth organic shapes float in a warm orange radiating mass: like complex root systems or phytoplankton in the upper sunlit layer, these biotic organisms record the dynamics of two artists working together.

The totality of the outcome is negated, and the creative partnership is embraced as a potential way for developing new visuals, built on a shared act rather than an individualistic view. Here, drawing becomes the practice of unlearning one’s selfness, and training in an awareness of the Other present, specifically to record a responsive environment, instead of creating a solid piece.

Pille-Riin Jaik’s video Xeroines in the basement fills the space with female voices reading out loud the thoughts of Constance DeJong, Audre Lorde, Simone Weil and Valerie Solanas. The feminist passages ring out over the scenery of a former military base in the city of Paldiski in Estonia. This vast abandoned site in the industrial landscape looks like a dystopian scenario, and the voices walk like spirits along the shore, deep in the forest, over the water. They perform a critique of male supremacy and colonial violence, post-apocalyptic dryads. The theoretical excerpts evolve into a verdict on the devastated land, until it all finally flows into a song that is sung over the whole thing like an oratorio.

Pille-Riin Jaik’s video Xeroines in the basement fills the space with female voices reading out loud the thoughts of Constance DeJong, Audre Lorde, Simone Weil and Valerie Solanas. The feminist passages ring out over the scenery of a former military base in the city of Paldiski in Estonia. This vast abandoned site in the industrial landscape looks like a dystopian scenario, and the voices walk like spirits along the shore, deep in the forest, over the water. They perform a critique of male supremacy and colonial violence, post-apocalyptic dryads. The theoretical excerpts evolve into a verdict on the devastated land, until it all finally flows into a song that is sung over the whole thing like an oratorio.

At first, the film gives a strong impression of post-human imagery. However, it is not a spectacle of disaster. On the contrary, I believe that the artist fills Paldiski with vibrant feminist speech in order to articulate the urgency of radical transformation for Western colonial ecologies. Xeroines draws on the idea that a world based on discrimination and oppression cannot produce a sustainable environment. ‘No entity can escape enslavement under an ontology which can enslave even a single object’ (Suzanne Kite). It advocates the inclusion of a female perspective and a feminist discourse in environmental programmes, in order to understand the concealed political mechanism of the ecological crisis, and to develop relevant methodologies for eco-activism.

Overall, by taking a female, sensual and poetic approach, the exhibition Parasitic Symbiosis envisions creative reciprocity and co-dependence in artistic collaboration as an inspiring pattern to follow for reinventing our relationship with nature and reimaging a potential future away from paralysing catastrophism.

Photo reportage from the exhibition.