Does dystopia express the damned? Does pure express distortion? What would be the binary opposition of pure? Damned?! It could be. The concept of pure is a relative and non-material idea that relies on the context of the financial, cultural, and, of course, political condition. It refers to something authentic and whole that is not distorted by anything else. While Damned signifies a curse, sinful activities, twisting and torqueing to normativity and stability, Pure can be considered as the oppositional binary of Damned against the background of binary politics.

This exhibition, The Pure and the Damned, a dual art show by the famous absurdist Estonian rapper Tommy Cash and the iconoclastic American fashion designer Rick Owens (based in Paris), is an eerie manifestation of their visual language by breaking the binary and normativity of seeing. But after visiting the whole exhibition under this title, an obvious question strikes me: are they trapped in binary politics through their own thinking? They put two oppositional binary thoughts, the words ‘pure’ and ‘damned’, and joined them with the conjunction ‘and’. Isn’t the normal way of oppositional seeing twofold? For example, man and woman, good and bad, colour and grey, East and West, ugly and beautiful, white and black skin, and so on in our everyday lives. However, with or without that stirring question, visitors can have an awe-inspiring experience of the two different worlds of Tommy and Rick, where body, mannequin and colour interact, through painting, clothes, video, sculpture and sound. This is Tommy’s first exhibition on the Estonian art scene.

Curated by Kati Ilves, the exhibition showcases a series of Tommy and Rick’s individual works, as well as a few collaborative works, including the music video Mona Lisa. From her point of view, ‘Cash’s visuals feature a great deal of aestheticised uncanniness, whereas Owens’ practice carries a kindred approach to the balance between functional design and the pure manifestation of form’ (‘Tommy Cash and Rick Owens’ kumu.ee). The exhibition opened on 3 May, and will run until 15 September, on the fifth floor of the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn.

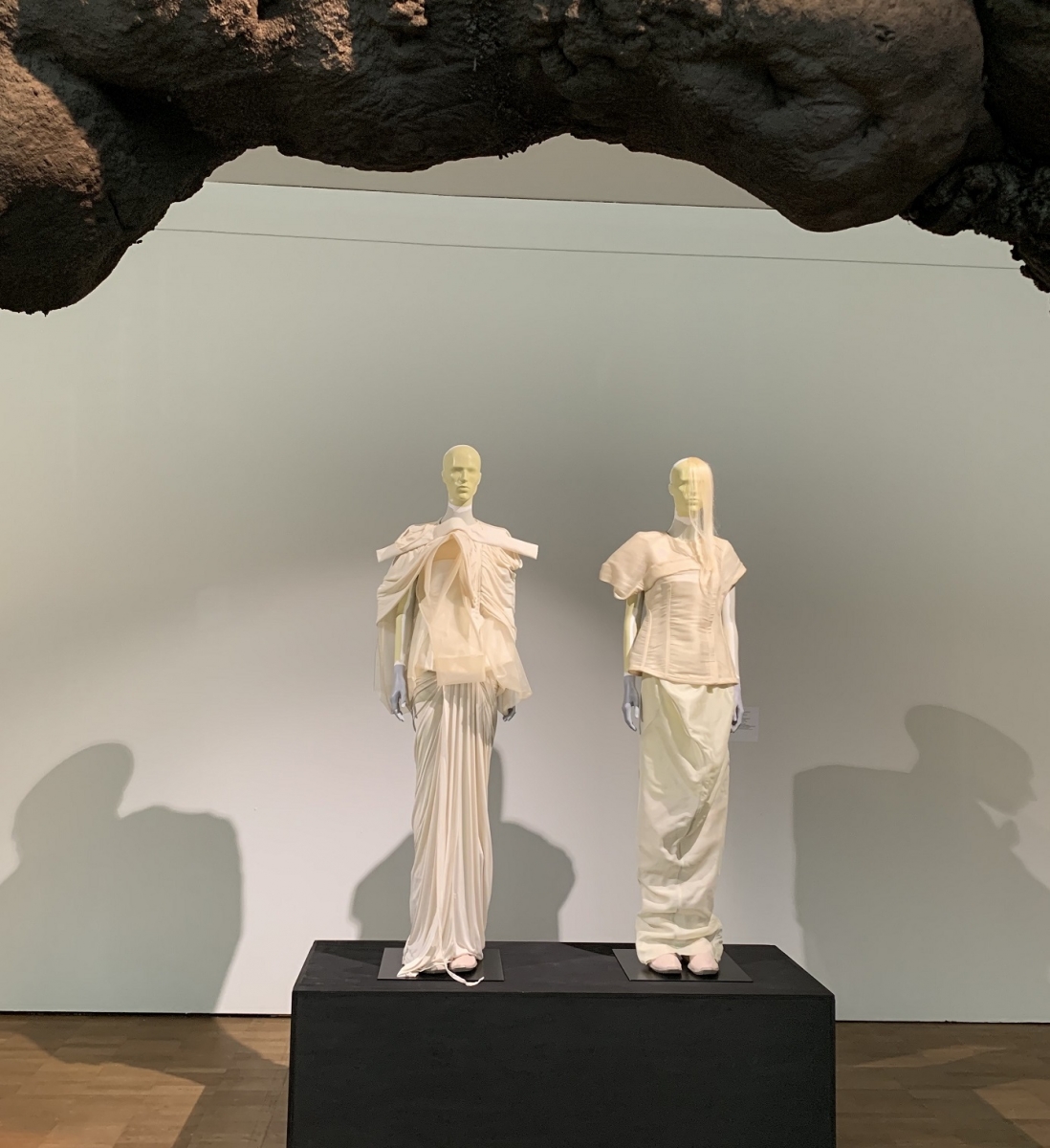

Tommy Cash and Rick Owens. The Pure and the Damned. KUMU, Tallinn, 2019. Photography: Aušra Trakšelytė

After entering the exhibition, the very first sculptures of a rabbit and a wolf are not the first works displayed in the show; instead, the last part of Tommy Cash’s work is in the gallery. Then the gallery’s right side directs visitors to Cash’s world, and the left side is Owens’ world. Between these two, a passage showcases their togetherness, the music video Mona Lisa that they produced in 2018. Most of Tommy’s artworks are recently produced, mainly from this year, and Rick displays his collection from 2006 to the present day. While Tommy’s land is colourful, with different forms and dystopian contents, Rick’s space stands with faces and faceless mannequins and postures in various designs and cuts of clothing that dissolve in a cloud of damned: grey and loud.

Mona Lisa is a collaborative production, in which they contributed both the lyrics and the visuals, encased in Tommy’s latest album ‘¥€$’ (2018). Around five minutes long, the animated colour video improvises on Leonardo da Vinci’s famous portrait of the Mona Lisa, and incorporates their bizarre imaginations in the form of Renaissance painting. They include their own bodies, da Vinci and other characters with 16th-century European gestures, and blend with the contemporary essence, where Tommy is ‘the slave with a golden chain met Mona Lisa on a bus line’, and Rick finds himself ‘stoned all my life like a mannequin’. Some of the visuals produce a satirical and funny feeling towards the traditional, classic reception of art: for example, Tommy’s tongue is turned into a hot dog, Rick’s into a slice of pizza; Tommy flies like a superman while his penis suddenly drops down from on high; an anxious da Vinci has closed the curtain as he saw marijuana leaves outside his window.

While visiting the exhibition, the question popped up in my mind, how did they get together? Artists have no borders, no country; however, there had to be some bridge that put them together. The Estonian rapper and visual narrator Tommy Cash first racked up widespread attention in 2016 through the bizarre visuals to the song ‘Winaloto’ on his first album, which the British music journalism website NME (New Musical Express) claimed to be ‘the most unsettling music of all time’ (‘Is this the most unsettling Music Video of All Time? Yes. It is’ nme.com). In the video, Tommy puts his visual as well as his musical signature by garnering different bodies, skin colours, and specifically, his own face superimposed on to an actual vagina. Then later ‘Little Molly’ (May 2018), ‘X-Ray’ (March 2018) and ‘Pussy Money Weed’ (January 2018) set the tone of his visual narration by breaking the stereotyping of the body and gendered identity, the value of a different dominant currency, hallucinations into drugs, a distortion towards normativity.

On the other hand, the American fashion ultraist Rick Owens has been active in the design world since 1992, and devised his signature tune through glamorous black-and-white colour, cutting and stitching. Online records show that Tommy was first picked up by Rick in the middle of 2018 for his fashion show in Paris, called SS19 menswear show. In one segment of the show, he wore clothes Rick designed, and went on the catwalk, while his two songs were played to it.

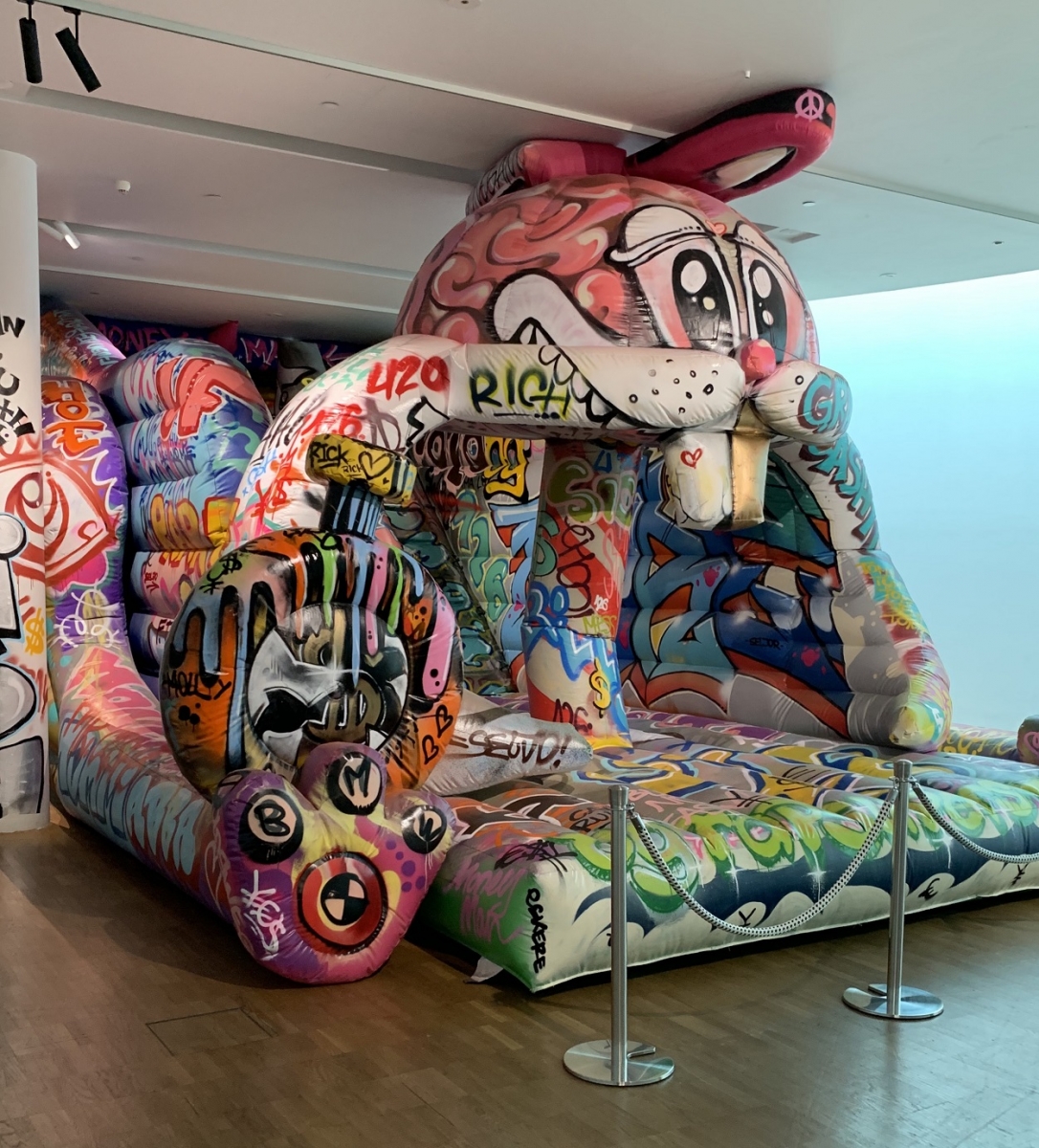

The right side of the gallery shows 13 individual works by Tommy Cash in the form of oil paintings (based on 3-D drawings), sculptures, graffiti and installations. In all the works, he uses his body as the grounds for experiment, where the contents of art are stories of oddity. In the painting Testosterone Tyrone, he plays with the male hormone testosterone that depicts his body hugely muscled, while Pampers shows the effect of the female hormone progesterone, a very pregnant woman’s feature in his male body. Some might say that these two paintings are grotesque; however, it is very clear that he questions the seeing of gender binary. Quality Time flattens his tone of breaking the binary, on which a muscled woman posits on top of his tiny, thin male body; it seems like a reversal of the missionary sex position. The dystopian sex act crawls then to The Horses, a painting that features a threesome of horses.

His work Graffiti Castle continues signifiers of his music video, such as love, the Euro, Dollar and Yen currencies, and marijuana; and his face with a distinctive pencil-like moustache. A pair of flip-flops made from bread adds his innovative imagination of footwear. Concurrently putting his live sperm in a small tank boosts some curiosities in the visitor’s mind: what’s the point? Is he encouraging visitors to buy his sperm? Who knows? A popular rapper could turn into a marketeer: maybe or maybe not.

The left side of the gallery is Rick’s land, which features raven jackets, coats, ellipse dress, seahorse dresses, stockings, tee shirts, jerseys, and wide trousers. These are crafted from cotton, silk, wool and nylon. Four parts of the gallery comprise a contrast between a dark and an off-white colour, where Roman status-like mannequins have made a strange orchestra, which takes audiences not only on a seeing experience, but feeling too. The most insane feeling strikes us at the beginning of the artworks, where three sets of mannequin pairs stand by holding each other like a backpack from the front, and from the back too. Wearing black tee-shirts and off-white long shorts, boots, shoes and black socks, the first of the sets creates turbulence: is it a backpacking pose, or the 69 position in the sexual act? And this set of mannequins evidently displays Tommy’s and Rick’s face and figure.

In Rick’s land of clothing design with significant face and faceless mannequins, I sometimes felt crowded. It requires more space to see these functional artworks from a distance. The details of each design are also confusing to identify with, as the direction is not clear.

This collaborative exhibition neither produces any pure or traditional perspective, nor provides any kind of oppositional two-fold thoughts. Instead, it is a space to get experience of many folds, many ideas, and many colours; it is a perplexing and delightful show.

References:

Cooper, Leonie. ‘Is this the most unsettling Music Video of All Time? Yes. It is’ nme.com July 21 2016, https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/tommy-cash-disturbing-music-video-estonian-5440

‘Tommy Cash and Rick Owens. The Pure and the Damned’ kumu.ee. https://kumu.ekm.ee/en/syndmus/tommy-cash-rick-owens/

[sr1]Ultraist, I think this word is more suitable than “iconoclast” and another point is I have already used this word (iconoclast) at the beginning).