Wagner Hall V.S. Monumento Continuo

Since year 1516 when Thomas More published his book Utopia the topic became a must for a left wing intellectuals. Discussions about perfect society constantly reemerges during the periods of crisis, fast transition and when individualism reaches excess. Utopia is not only a dream which never was and never will be, it is an island of new perfect order where we are living in consensus with our fellow human beings and in the harmony with a land which is inhabited by us. Can one still dream about ideal cities, good places and egalitarian societies in the era of individuality and does it make any sense in this globalized world? Apparently it does even more than ever and in order to dive into the topic of Utopian City you need to pop up in Riga where Survival Kit International Contemporary Art Festival took place.

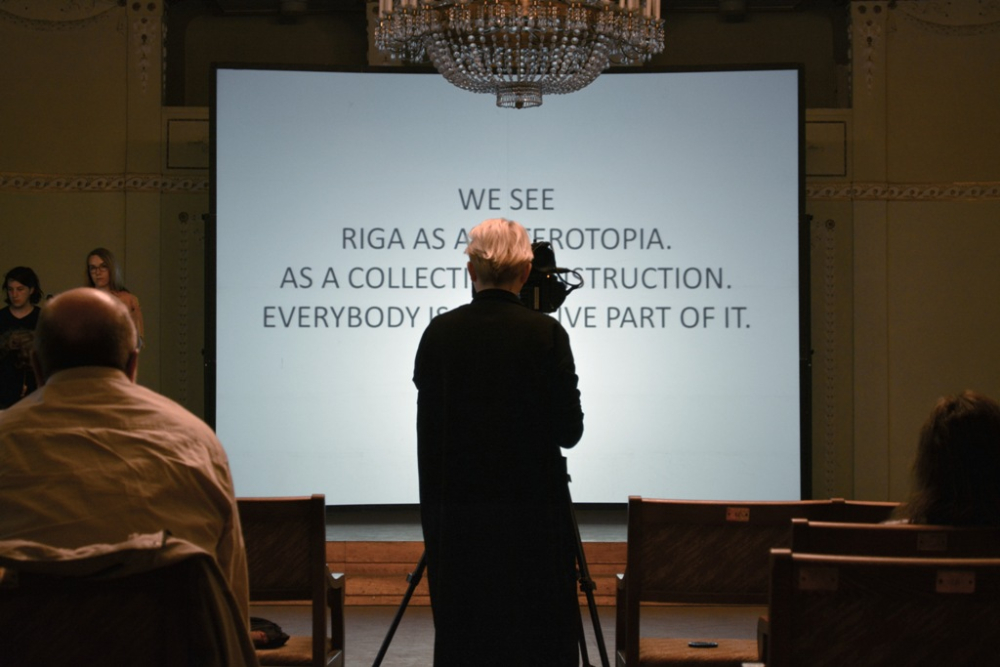

So here I am in the Wagner Hall, minutes away from the bus station siting in a clumsy, squeaking chair and listening for the speakers of “Urban Utopia: Art and Culture as a Tool for Exploring and Researching a City” seminar curated by Solvita Krese (LCCA) and Jonas Büchel (UI). Poorly recreated chandeliers in the spacious interior of an old Classicist style building create perplexing scenography for the first day’s session. Awaiting their turn are the speakers of the event consisting as usual of city activists who are brave enough to be idealists, urban designers and architects who like to stress their involvement in broader discussions, artists – concentrated in agenda of their own and finally a small bunch of people who came here just to show off. It’s easy to feel informal within such a company and a noisy coffee machine standing next to me helps to emphasize the mood.

Camilla Topuntoli filming the presentation of the Free Riga initiative

City activists such as Charles Bušmanis, Jekaterina Lavrinec, Free Riga initiators and others usually have a clear idea of what kind of cities they need and they know what kind of future to promote. Most of them are supporting cooperation, praising community and looking for a new forms of togetherness. They defend the mixed working-class environment and stand against the dense high-rise developments of contemporary capitalist city. They are fighting even if their beloved neighborhoods may be destroyed by a wave of gentrification. It is too easy to be skeptical towards their idealistic approach, but irony and cynicism might be an end in itself as rightly observed by David Foster Wallace.((“Irony and cynicism were just what the U.S. hypocrisy of the fifties and sixties called for. That’s what made the early postmodernists great artists. The great thing about irony is that it splits things apart, gets up above them so we can see the flaws and hypocrisies and duplicates. … The problem is that once the rules for art are debunked, and once the unpleasant realities the irony diagnoses are revealed and diagnosed, “then” what do we do? Irony’s useful for debunking illusions, but most of the illusion-debunking in the U.S. has now been done and redone. … All we seem to want to do is keep ridiculing the stuff. Postmodern irony and cynicism’s become an end in itself, a measure of hip sophistication and literary savvy. Few artists dare to try to talk about ways of working toward redeeming what’s wrong, because they’ll look sentimental and naive to all the weary ironists. Irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving.” (Quote from The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature edited by Joe Bray, Alison Gibbons, Brian McHale) )) Of course optimistic simplification of human nature might easily delude listeners and drag them to fiction. But do we have other choice? After all, it might turn out more fruitful and lead us towards something more exciting than rational pragmatism. We need to both reflect and to criticize utopias, but at the same time we are doomed to enjoy them, promote them and hope to see better cities in the future.

Plavnieki mass housing district in Riga

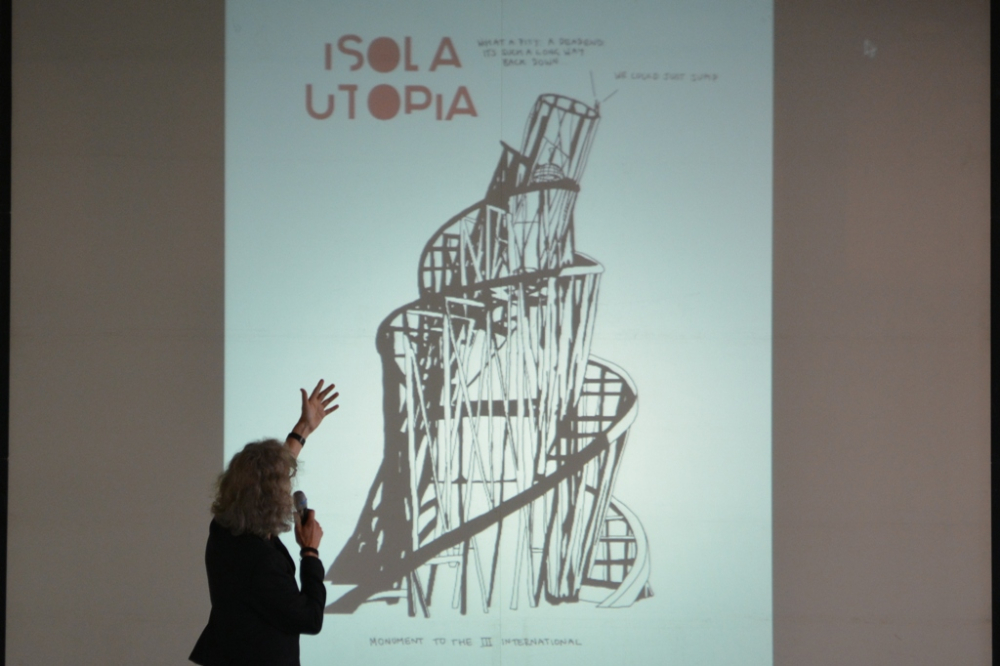

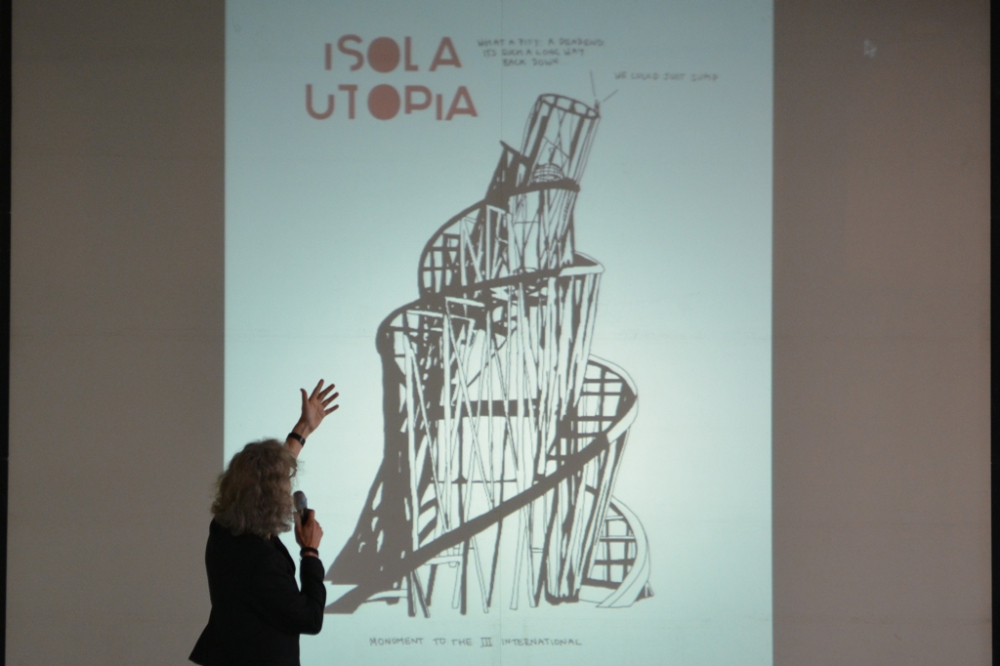

Fiction is inevitable when speaking about utopias, so presentation of Catalina Niculescu makes me wonder why the Bauhaus, according to her, was the first modern utopia. Why Ebenezer Howard didn’t meet the criteria? And what about the urban visions of Tony Garnier Industrial City, Clarence Perry’s Neighborhood Unit and proposals made by Russian constructivists in early 20s? Apparently for Catalina none of them were good enough to be modern or utopian. High point of the presentation was reached when the technocratic science fiction of Jacque Fresco (The Venus Project) was called a Smart City and the Superstudio’s Monumento Continuo was not presented as an Anti-utopia, but as Utopia instead. Apparently it is little or no sense in discussing modern utopia only through the means of aesthetics, technology and spatial structure. Physical form of utopia is just a skin of a beast, while ideology is it’s flesh. Utopia is bold, it is critical and it is definitely political.

In an interview given to the MONU magazine on urbanism Superstudio’s founder Adolfo Natalini named((http://st-ar.nl/deadly-serious-%E2%80%93-interview-with-adolfo-natalini/)) Monumento Continuo as Anti-utopia which was envisioned in order to warn the society about the consequences of technocratic thinking and false adoration of monument as the “most powerful way of expressing yourself and society”. Superstudio provided us with a statement while Jacque Fresco presented old modernist ideas as a new salvation to the present day society. Fresco mixed socialist ideology with the new technology as a real engineer, but not as a humanist. Engineers and city planners think about the large cities as the solution to our environmental, social, and economic problems due to smaller footprints, density of people, effective social control, concentration of culture and resources. Artists think about the contemporary city as a place of poverty, social disadvantage and other societal problems created by the market or political forces((http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/sep/24/manifesto-fairer-grounded-city-sustainable-transport-broadband-housing)). Conflict between these two approaches is inexhaustible.

Improvised flea market

Ania Szremski curator at the Townhouse contemporary art space in Egypt is one of those who have faced the political pressure. Cairo is “quite a place” for an art institution – political conflicts, revolutionary uprisings and social tension. Townhouse might be a great example of devotion and idealism, but is this a form of Utopia? You might name your day to day work as steps towards it. For the other curator, left-wing political activist, Airi Triisberg participating in an informal art workers network in Tallinn and living in a housing collective in the city of Leipzig is her form of practicing utopian lifestyle. Ironically day one of the seminar ended with the film session packed with old soviet propaganda movies depicting airbrushed life in communist country. It seems like setbacks of the regimes from the past created a lush environment for a reactionary utopias discussed today.

Next morning Artis Zvirgzdiņš and Jonas Büchel took us for a small tour around the city. We, a group of twenty or so people, drifted around an urban environment of Riga trying to play a game of psychogeography. I never lived in Riga and for me it is heterotopia by itself. It is always that other place where I land and after short sequence of events fly away. It is alien, but at the same time familiar. You might say that all the post-soviet cities are alike, but it is simply not true. It looks different, it smells different even if some of it is the same. Last stop of our tour is part of this legacy, yet another glimpse of failed utopia. It is a beautiful piece of pre-war industrial architecture built by a leather shoe manufacturer and later used as textile factory by the soviets. Second day of the seminar is going to take place here – in Boļševička.

Former textile factory – Boļševička

Most of the speakers today are either artists (professionals, self-educated activists sociologist etc.) or designers (urban designers, architects, media specialists – you name it) and it is easy to spot the difference. It’s hard for an architect or designer to step back and critically reflect the current condition. They operate within strong constrains and usually their work is interconnected with the means of power and authority. There is no big difference if you are established city architect as Karolina Keyzer is or a young active representative of a Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design. You are limited by the power provided by the citizens, government or by the investors. You are always dependent on political climate, economical bubbles or public opinion and you need to admit that. Instead it was denied to reflect upon in Strelka’s sales pitch presented in prorogating rhetorics borrowed from venture capitalists or PR agents. It is hard to imagine anyone building a “Utopian Education” while flirting with sharp teeth business people.

Jekaterina Lavrinec presenting the “Street Komoda” project

To present yourself as research based, visionary, somehow alternative practice involved in the broader discussion and supporting social change became cliché of today’s creative market. To promote this fiction became necessary not only for architects, but for city activists, scholars, urban designers and artists as well. Couple of buzzwords placed in the right order and bunch of false promises is perfectly enough for most of them, mainly because they are not going to devote themselves to the topic. A perfect example could be Bosco Verticale((http://www.archdaily.com/195866/in-progress-bosco-verticale-boeri-studio/)) project in Milan, Italy. It was presented in a number of architecture websites as a vertical forest which “brings life into areas of the city”. In bulk renderings project looked like continuous monument of Superstudio regained by nature, dystopia concurred by the power of utopia, but the next speaker of the symposium introduced audience with the other side of the coin.

Bert Theis is an artist and co-founder of the Isola Art Center formerly located in the abandoned factory in the Isola neighborhood in Milan((http://www.isolartcenter.org/)). For four years it was used as the place for various artists and local people to gather and to participate in creation of active cultural environment. When the government of the city decided to evict the area in favor to some big business Isola became a battlefield between creative community and the developers. Bosco Verticale was one of those projects designed in the area as a part of the massive redevelopment project. Two towers were built in a park and one more cliché of today’s architectural world was materialized – tower planted with trees. It’s not a peace of stacked landscapes as the MVRDV Netherlands Pavilion at the 2000 World Expo((http://www.archined.nl/en/reviews/expo-2000-nl/)) was, it’s not a statement or a “new nature”. Straightforward marketing – that’s what it is. Struggle of Isola presented by Bert in his energizing speech is an art work in itself. Named as a “fight-specific” art((http://www.isolartcenter.org/index_eng.php?p=1131987010&i=1131987022)) pieces realised in Isola were exhibited in the Boļševička during the Survival Kit Festival. Despite the pressure Isola Art Center is still operating within the neighborhood powered by idealism of Bert Theis which is something worth admiration.

Bert Theis presenting the Isola Utopia

Answering even if rethorical question posed in the seminar whether „ abandoned spaces, deserted urban landscapes and the wastelands of our society stimulate and transcend our behavior and imagination?”, I‘d say that the actual city of Riga was the most thought provoking “speaker”. On a first day of my trip I passed an old folk singer asking for money in the street. It looked absurd to see woman dressed in a folk outfit in a middle of the touristic heart of Riga city begging. Echo of agrarian communities which were transformed by the serfdom and later by the first wave of industrialization. These changes altered not only social relationship between locals, but physical environment of towns and villages. Industrialism was followed by a wave of patriotic nationalism, patriotic nationalism was conquered by socialism and finally switched to global capitalism. Transformation appeared to be the only constant process in the city and the only real designer of our habitat. Yet artists and urban designers are brave enough to think they can affect these processes. Instead, they are molded by forms of power, political and economic ideology. The only thing which is left to us, educated middle class citizens, is to reflect, glorify or criticize.

Urban Diving with Artis Zvirgzdiņš and Jonas Büchel

Photographs by Matas Šiupšinskas