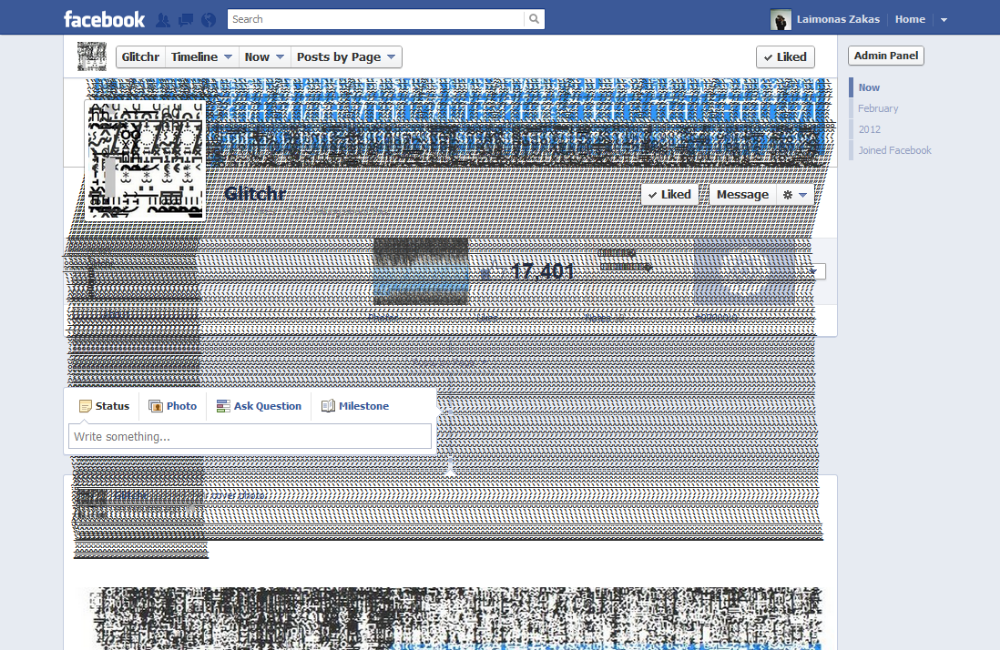

Laimonas Zakas ‘making out’ of Facebook interface, project started in June 2011

This summer I was chatting with Laimonas Zakas, a Lithuanian-born artist-hacker-videographer, who is currently studying at the Hague Royal Academy of Art. Laimonas Zakas mentioned to me that he was invited to participate in The Wrong Biennale by Brasilian curators and that they were going to show his Glitchr project.

Glitchr is a project that was started by Zakas back in 2011, when he was coding stuff online just for fun and started using bugs he had discovered in the Unicode system that allowed adding an unlimited number of diacritical marks to one character. Using these bugs, he ‘could create a kind of a text which extends the ordinary web-page limits (including Facebook, Google, Twitter, etc.).’ He started creating abstract graphic bodies which were adding distortion layers upon the usual interfaces of internet sites and social network platforms. The first acknowledgement of this work was an exhibition at Jonas Mekas Visual Arts centre in Vilnius, curated by Ignas Kazakevičius.

The Wrong Biennale, where Laimonas Zakas is included among other artists, has kicked off on November 1st and is free for everyone to visit. This Biennale is organized by Brazilian curator David Quiles Guillo. Guillo is also the founder of ROJO as well as NOVA Contemporary Culture Festival that featured more than 600 artists and musicians from all over the world. In comparison with his other projects, Guillo’s The Wrong Biennale, with it’s 30 Pavilions and 300 artworks, makes big-scale format Guillo’s special feature.

However, one could argue that 300 artworks exhibited in 30 Pavilions is enough to show how expansive and all-encompassing net-art can be. Due to the nature of internet (free space and infinite access), this type of all-encompassing world-wide biennale could probably host 10 times more artworks.

It seems that The Wrong Biennale has all the features to mimic the ‘real life’ biennale. For example, 30 Pavilions and 300 artworks were exactly the number that the viewer could hope to ‘digest’ in one day, taking a quick look at each of the artworks without the need to return once again. It’s as if you had gone to Limburg last year to see Manifesta in a former coal mine factory. One intense day – and you are done. Just without travelling (in the case of Wrong).

What is different here from the major ‘real life’ biennales is that the curatorial idea for selecting certain artworks is quite unclear as there is no theme for the biennale, not even a text that could give one an idea of the path of thinking the main curator might have taken.

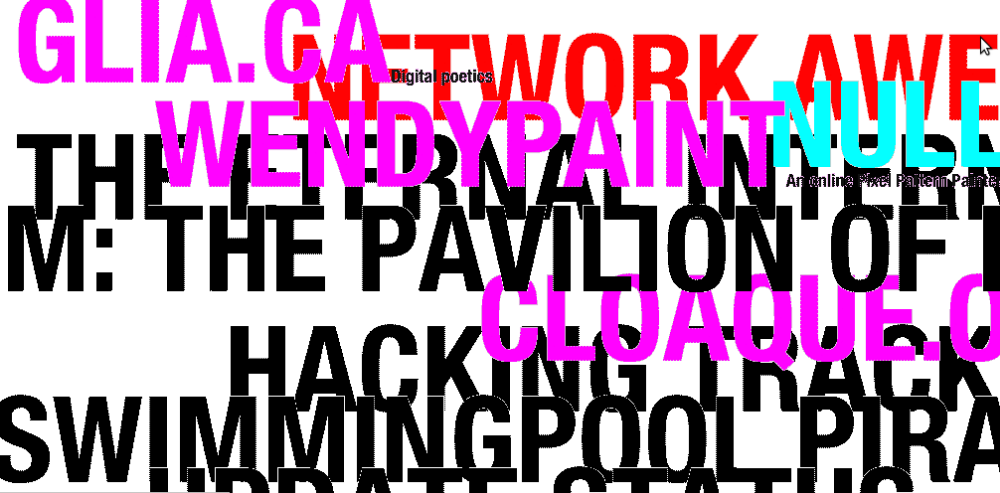

Screenshot of The Wrong’s home page

Each Pavilion, curated by an invited artist, has its separate theme and structure. Maybe it is an ironic online version of the Venice Biennale with competing national Pavilions. It is as if the curators of The Wrong were taking us for a walk through Giardini where buildings function as separate art venues for particular national projects and manifest different discourses, show different curatorial attitudes trapped in this real estate materiality of buildings and emphasize the legacy that Venice brings onto them. Or maybe The Wrong could be likened to the entropic edition of the dOCUMENTA 13 or the 9th Mercosul Biennial with its time and space-curator positions?

One of the highlights of The Wrong is the Pavilion called Soci4lites, curated by Emilie Gervais. Among the artists featured in the Pavillion is Stefani Germanotta, our good old friend Lady Gaga. The work by Lady Gaga is simply a link to her website and, I guess, following any other associated links you can find out that it’s about Lady Gaga’s online presence – once you type her name into a search engine like google, youtube and others. What an easy game of curating, it seems – just put a link to whatever already exists. No criticality, no reflection, just surfing on whatever there is.

Soci4lites pavilion, curated by Emilie Gervais

I guess most Wrong Pavilion curators mainly engaged in the old debate of how some net artists are being disregarded by young net artists and how these young net artists are just tramping on what net art did in the 1990’s and the democratic ideals that net art stood for back then.

Back then it was all about Transmediale, coding and open source software. A hugely idealistic social project to redistribute control evenly. However, what was happening 10 years ago might no longer be relevant today. Social media explosion made us hooked on and glued to gadgets and addicted to wifi. Users do not try to learn to code their own search engines or social media sites (yet, still?). What changes, then, has the new net art brought? And if they did, why these changes are so obscure in the Wrong Biennial?

Network Awesome pavilion

As Claire Bishop has noted in her essay published a year ago in Artforum, there exists a divide between net art and contemporary net art because of the way artworks can be sold. It all boils down to the fact that contemporary net art is shown (and sold) in the form of videos, installations and sculptures (huh?) rather than coded systems of internet architecture. It is still hard to sell videos, not to mention coding or temporary programme that disappears with time.

Besides problems of selling and showing net art, there seems to be another contradiction that I would call the fight between method and aesthetics, the fight that somehow slows down the development of net art’s discourse. One of the curators at The Wrong, Curt Cloninger, describes contemporary net art practices as ‘contemporary retro-glitch campy bad prosumer-FX fetishism that so frequently pats itself on the back as novel in certain tumblr-centric, gif-centric contemporary net art circles.’

In what should allow a myriad ways to experiment and introduce different artistic strategies, The Wrong Biennale chose to display artworks where artists have spent most of the time for the development of techniques of coding or modification of existing content. Swimmingpool Pirahnas Pavilion offered a glimpse of aesthetic examples of the tokens of net art: lo-fi 3D modelling; collages and montages of found audio and video material, distorted screens, somewhat disrupted social media collages and ironic reworks of online advertising. DIY approach here seems more like a safe oasis than an attempt to formulate a critical approach or reflect with a certain distance rather than re-perform the existing aesthetics.

There is a threat that these practises are appropriating internet but do not go deeper to expose the structures that rule its logic. However, not all net art is ignorant of these matters. At the first glance, artists like Laimonas Zakas seem to be interested in retro-glitch aesthetics. He does not articulate a critique of social media. His project does not point to social media as a platform of affect production that is a completely controlled frame of social interactions. He is not interested in the issues of power and control.

At the same time, Glitchr does not simply re-perform internet rationale, it inhabits the sphere of tracking mistakes in corporate coding systems that constitute the control. It also exposes the power of coding tools and the power that it gives to one person over the corporation of Facebook. Bugs in the systems do exist, and we can/should use them for our own purposes – and Glitchr is offering you to take control, to use your own social media page through that distortion.

Controversy lies also in the fact that Glitchr actually helps Facebook. It allows programmers to track their Unicode bugs left in the system and fix them – simply by following Laimonas Zakas coding. So here appears the trap of net art – whatever net art one produces, it simply brings more money to internet providers and new internet start-ups and entrepreneurs and internet system architects. It brings us back to the medium of internet, which is both a business structure, a content hole and an affect generator.

But maybe not everything is so gloomy. Maybe it is the Glitchr approach that can point to the future of internet users. What Zakas says through Glitchr is that either we all learn to code and thus be free from corporations, or the corporations will do the work ‘for us’ and offer their services, for which we pay by participating in their controlled frameworks. Glitchr points to the unexplored niche where not just art, but also a lot of control can be taken over and a lot of money is yet to be made. The question now is who will be the first.