„Archeology and the Future of Estonian Art Scenes” (19.10.12 – 30.12.12) in KUMU is an exhibition assembled by four Estonian curators—Eha Komissarov, Kati Ilves, Rael Artel, and Hillka Hiiop—with the aim of giving an overview of contemporary Estonian art. To do this the curators have mainly focused on Tallinn, Tartu, and Pärnu—the three main centers of artistic activity for the past 30 or so years in Estonia—along with the institutions and groups which have shaped the contemporary art landscape there. The conceptual linchpin of the exhibition is Hillka Hiiop’s doctoral thesis about the problems of conserving and exhibiting contemporary art. The press release states that the contemporary art landscape is characterized by pluralism and a lack of cohesion. Furthermore, the museum’s function has changed as well. Traditionally the museum was a keeper and presenter of cultural traditions. This, however, has changed with the museum becoming the primary commissioner of contemporary artworks. According to Eha Komissarov, the exhibition presents one of the ways in which the general pluralism of the contemporary art landscape in Estonia could be summarized in a general overview that would include both artists and institutions grouped by different ideologies and technologies.

The keyword, sadly left woefully unanalyzed and unexplained, functioning as a structuring principle in the exhibition is ‘scene’. It is stated in the exhibition text that ‘scene’ is a term with an international spread, which is derived from Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the cultural field, and that a ‘field’ is a relatively autonomous social universe, necessarily connected to and influenced by other fields. The term ‘scene’, according to the curators, has been successfully utilized throughout the world as referring to the field of artistic production, which is governed by its own ideology. And this is where the troubles begin. As far as I am aware and other Estonian critics have stressed that [1] Bourdieu’s theory of the cultural field does not employ the term ‘scene’ in any significant way. The curators have arbitrarily equated the term ‘scene’ with the term ‘field’. Unfortunately this has made the term ‘scene’ meaningless in the context of the exhibition.

To see this consider the “scenes” assembled in the gallery.

The “Tartu painting scene” (the label actually refers to a local school, not a scene) has largely converged around the Department of Painting in the Institute of Cultural Sciences and Art at the University of Tartu. Then there is an “artistic intervention scene,” an “artistic research scene,” (both actually designating methods) the “‘Köler Prize’ scene” (referring to an institution) of The Museum of Contemporary Art of Estonia, and a scene labeled “Glamorous Leftism” (a lifestyle instead of a scene) Next there’s a “scene” called “Explosion in Pärnu,” (another local school) which gives a chronological overview of the artistic activity in Pärnu from 1993 onwards, and covering quite recent developments. This was probably one of my personal favorites. Not because of the artists on display but because of the way that the space for displaying them was utilized: walls covered with artworks from top to the bottom, which were interspersed with clippings from newspapers and magazines about the works and their authors.

Then there is the cryptic “Old News” scene consisting of artworks that deal with Estonia’s contemporary social realities. Topics like the economic crisis, the rights of minorities, unemployment, nationalism, and consumption are covered. “The Tallinn-Amsterdam Axis of Graphic Design” (actually referring to geographic locations instead of a scene) focuses on the works of Estonian designers who have been educated in Holland. “Text Art and Psychogeography in Tartu; EKSP” (designating yet another local school) consists of language and text experiments along with metaphors of place. This is a phenomenon uniquely tied to Tartu since many of the authors have backgrounds in semiotics, philosophy or other disciplines within the humanities. Besides these, there is also a “scene” made up of Estonian artists studying, working, and residing in London, along with probably the most curious “scene” of the whole exhibition – Jevgeni Zolotko, a one-man scene. (This just boggles the mind.)

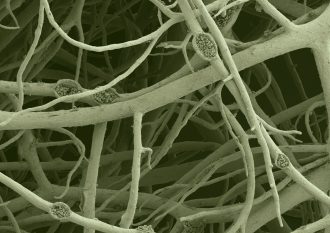

In addition to these, Hillka Hiiop has put together a small exhibition dealing with the topic of her PhD dissertation—the conservation of contemporary art—consisting of works from the museum’s collection. The works have been selected according to the conservational problems they raise for the museum and its employees. For me this was probably the most interesting part of the whole exhibition. Contemporary art is often ephemeral, and this presents some intriguing dilemmas for the archiving and subsequent exhibition of artworks. Hiiop’s exhibition gives a few clear examples of such dilemmas and illustrates them with selected works. But if this small exhibition is supposed to be a “scene” as well, then I’m truly at a loss about what the term means here.

The foregoing should clearly show that “scene” is employed haphazardly and inconsistently to designate groupings which have been assembled according to quite diverse criteria. The gratuitous use of the term ‘scene’ to designate all of these different phenomena is bewildering. Because there are no commonalities between the referents of the term ‘scene’ it simply loses its meaning. The curators do not supply the viewer with an explicit explanation of how they use the term, therefore it becomes useless as an organizing principle purporting to render sensible the groupings brought together and presented side-by-side in the gallery.

This has already been noticed by other Estonian critics writing about the exhibition—Maarin Mürk, Hanno Soans and Margus Tamm, for instance, have all pointed out the ambiguities of the term ‘scene’ and how it is misused as a categorizing principle for organizing the works in the gallery. Soans has concluded that perhaps the term is not appropriate to characterize the multifaceted landscape of contemporary art. Tamm has, instead, tried to find a new meaning for the term as a categorizing principle. His conclusion is that the term, in the context of this particular exhibition, only makes sense when interpreted from the museum’s point of view. It is an umbrella term used by the national museum, located in the nation’s capital, for ordering and delimiting the diversity of artistic activity surrounding it. Thus, Tamm concludes, the focus of the exhibition is not so much the landscape of contemporary Estonian art, but this very landscape surveyed from the narrow point of view of a particular museum. While I largely agree with this interpretation, I’d like to go a bit further in my own, and claim that the exhibition is ultimately not at all about the field of contemporary Estonian art. It is, instead, an exhibition about the museum as an institution and a player in the artistic field. In other words, the exhibition consists of the KUMU art museum laying itself bare as an institution.

To argue my point, I’ll disentangle the term ‘scene’ from the term ‘field’ and drop the former for it would only foster further confusion. But before going further, I’ll analyze another term, also present in the exhibition’s title, which might provide the key for understanding the agglomeration of “scenes” on display. That term is ‘archeology’.

In a nutshell, the archeological method, as outlined by Foucault, studies discourses. The goal is to discover hidden historical discontinuities, exclusions, ruptures and breaks in the development of the discourse being studied, and to elucidate the network of connections it has with other discourses. A diffused discursive system is called a discursive formation, the conditions of forming objects of discourse are the formation rules, and theories within a discourse are strategies. Discursive objects emerge from a network of necessary and historical conditions. These are the relations between different institutions, social and economic processes, normative systems, etc. that allow the object to appear and situate itself in relation to other objects in the field. [2]

Let’s, for the sake of argument, suppose that the “scenes” can be equated with discourses, the works with discursive objects and theories behind them with strategies, and the set of scenes on display with a discursive formation. If any archeology in the Foucauldian sense has been employed in compiling the exhibition, one can’t tell if this is the case by looking at it. An archeological approach would have tried to show how one “scene” is related to others, it would have uncovered its position in a tangled web of historical heterogeneous relations. Yet as it stands, for the viewer, the various “scenes” seem almost monadic in their isolation from each other. The discursive formation is not publicly elucidated. Thus the viewer is presented neither with “scenes” nor with an archeology. It seems to me that the notion of ‘archeology’ is of no help either.

The press release mentions Bourdieu’s theory of the cultural field. Let’s look at the exhibition through the lens provided by this theory. I’ll give a truncated account of it, touching only upon those aspects that I need to make my case. A “field,” simply put, is a relatively autonomous social universe with its own internal laws. Fields can be encompassed by other fields. There are two structuring principles in the cultural field: (1) the opposition between the field of restricted production and the field of large-scale production; (2) the opposition between those who occupy well-established positions and the newcomers trying to either usurp those spots or to occupy yet unoccupied positions within the field, garnering recognition and social capital to them in the process. The field is composed of all the agents active in it and all the positions that the field can accommodate. The agents are individuals (producers, distributors, critics etc.), groups (other producers, the audience etc.) and various institutions (galleries, museums etc.). The cultural products occupying the large-scale side of the field are usually evaluated in terms of their market success. The products occupying the restricted side are usually evaluated in terms of their failure on the market, and their being consecrated by (vouched for) someone (e.g. a critic, an art dealer, an institution like a museum) who already has a considerable amount of social capital, viz. by someone who already occupies a respectable position within the appropriate part of the field. Yet another option, often employed by many newcomers, is to attack those in the entrenched positions and to undermine their authority, thereby accumulating social capital for their own positions. It is the struggle and competition for positions that characterizes the cultural field. The positions are characterized and defined in opposition to other positions within the cultural field. Competition involves struggles over legitimate characterizations of the field—this helps in situating a position in relation to others—and over the positions that have the consecrating power to vouch for agents and put forth, and establish, authoritative descriptions of the field. [3]

This is an incomplete characterization, but it will do for my present purposes. The “Estonian Art Scenes” exhibition does indeed present the visitor with the results of a multitude of position-takings within the Estonian artistic field. But because so little contextualization is provided, unless the visitor has a sizeable grasp of the history of Estonian art of the past 30 years, all the position-takings tend to become insipid in the context of the exhibition. But let’s say that the viewer does possess the prerequisite knowledge. Then the groupings presented, claiming to present a version of an overview of the field of contemporary Estonian art, seem puzzling and end up seeming somewhat arbitrary. They only begin to make sense if, as Margus Tamm pointed out, we take the characterization of the field underlying the exhibition as the one that the museum, as one of the agents with powers of consecration active in the field, tries to impose on it. But the museum is not just any agent in the field. Along with the educational system, it is part of a network of agents that have the power, despite the recent changes in the museum’s role, to compile and disseminate a culture’s tradition. This is done by selectively consecrating certain agents and products in the field. The “Estonian Art Scenes” exhibition is an example of the application of such a selection function to Estonia’s contemporary art. The result is not an overview of the field of contemporary art in Estonia. For this it is too partial and invested in the struggles taking place in the field. (The curators do not deny this. The press release explicitly states that the exhibition is only one of the many possible ways of organizing the field of contemporary art in Estonia.)

But it seems to me that there is more to the exhibition than that. For the curators could’ve been different, thus at least some of the works might have been different as well. (Probably not most of them because the chosen artists have been consecrated, or legitimated, by other influential players in the field which means that most of them are already well-established.) It seems to me that behind the artworks, underneath the curatorial work, the exhibition exhibits something more. The overview of the field of contemporary art in Estonia is not the core of “Estonian Art Scenes,” it’s not even a partial overview drawn from the museum’s perspective. Instead it is an unreserved exhibition of the museum itself as an institution, and an interested agent active in the struggles of the cultural field. While this could be said of any exhibition in the museum, what makes “Estonia Art Scenes” noteworthy is the unabashed way that the museum as a player in the field, along with its specific mode of operations, is put on display. It seems to me that this is the real object exhibited, whereas the artworks and their arrangement are merely the medium through which the museum, as a specific player in the field, can be shown.

[1] Hanno Soans, “Pärnakas, tartlane ja tallinlane kunstisaalis,” Eesti Ekspress. 20. November 2012. Online:http://www.ekspress.ee/news/areen/uudised/parnakas-tartlane-ja-tallinlane-kunstisaalis.d?id=65275150[Retrieved: 04.12.12]; Maarin Mürk, “Segadus skeenemetsas,” Artishok. Online:http://artishok.blogspot.com/2012/11/segadus-skeenemetsas.html [Retrieved: 04.12.12]; Margus Tamm, “Teeme, teeme uue skeene,” Artishok. Online: http://artishok.blogspot.com/2012/11/teeme-teeme-uue-skeene.html[Retrieved: 04.12.12].

[2] Cf. Michel Foucault, The Archeology of Knowledge, tr. A. M. Sheridan Smith. London & New York: Routledge, Routledge Classics, [1969] 2002, pp. 23-85.

[3] Cf. Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, tr. Randal Johnson. Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1993, pp. 29-141, 215-237, 254-266.

Have a glimpse of the exhibition. Photographs by Stanislav Stepaško: