I will make no secret of the fact that, despite my distaste for virtual reality, electronic gadgets and touchscreens, reading the news on my phone has become part of my daily life since the war started on 24 February, and with this the humour of the Ukrainian media, and Oleksii Arestovych in particular, which has allowed me to retain a smidgen of optimism, even as Russia carries out a fresh rocket or drone attack on Ukrainian civilians. This daily experience of mine had something in common with the ‘gray wave’ swelling in the customer hall of a former bank, the abandoned Neo-Renaissance building in Rīga’s Dome Square that the 13th Survival Kit exhibition inhabited this year. Rhythmically repeating itself, Krišs Salmanis’ kinetic image seemed to wash away and wipe all the alarming reports from the war. The work, entitled Wake Me Up When It’s Over, refers to the desire that consciousness has of surmounting the insurmountable (the war is still going on) in order to place it firmly in the past. It made me recall Salmanis’ solution to the hardly practicable objective of learning all of Haydn’s 104 symphonies: after recordings of the symphony were layered on top of one another and pressed on to a single vinyl record, every aficionado of Viennese Classical music could listen to them in the form of a uniform background noise (it seems that Haydn’s longest symphony does not last more than an hour).[1]

Installation view of WAKE ME UP WHEN IT’S OVER by Krišs Salmanis at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Nevertheless, the entire expressive spectrum of the language of art is located between conceptual ‘all-or-nothing’ solutions. What parts of this spectrum were highlighted in the Survival Kit exhibition, curated by iLiana Fokiananki and entitled ‘The Little Bird Must Be Caught’ (henceforth ‘The Little Bird’)? The notion of quality is urgent concerning politically oriented art. It should be either cast aside, as in Thomas Hirschhorn’s famous thesis ‘Energy yes, quality no!’, or else preserved. Claire Bishop, incidentally, commenting on Hirschhorn’s idea, writes that ‘Some [art] projects are indisputably more rich, dense and inexhaustible than others’ in the context of a specific time, place and situation.[2] Thus transformed, the notion of quality presupposes a sensitivity receptive both to the ideological element and the particular semantics of the language of art, and this sensitivity is best sharpened by exchanging thoughts. We talked about art that could fit Bishop’s criteria in a discussion that Basia Sliwinska, a guest lecturer at the Art Academy of Latvia, organised at small coffee tables on one side of the customer hall.

Of course, the context of a specific time, place and situation is not determined only by the war that Russia started in Ukraine. It is also a song of freedom, or birdsong, in line with the metaphor of the poem by the Latvian poet Ojārs Vācietis used for the exhibition’s title announcing current events. Numerous exclusively acoustic works have been included in the exhibition, and this is a conscious decision on the part of the curator, made, as she writes, in response to the isolation caused by the global pandemic, and supplemented by voices protesting against injustice.[3] With its interiors partly preserved, the historical fin de siècle building both amplifies and hinders the perception of works of art. Susan Philipsz’s sound installation The Two Sisters (2009), located in a large corner room with a vaulted ceiling, parquet floor and a huge safe on the side, is an impressive scene for a story told through an ancient ballad. It is not, however, as far-reaching and emotionally biting as, for example, Study for Strings (2012), the station platform in Kassel from which Jews were deported to concentration camps in 1941 and 1942.[4] Another audio-visual work could be heard and seen in a small room lined with dark wooden panels and large pillows, the tones of which, like the colour of the walls, were matched with Fred Moten’s fluttering clothes in Wu Tsang’s Girl Talk (2015). The sound and image invite us to sit down and lose ourselves in the uncertainty of corporeal identity. The presence of the voice and/or the body in a public space, even if only in digital form, as in this exhibition, has a performative political power of its own. But works that ‘keep silent’ can prove effective too. In other words, mere images are also capable of being decidedly performative.

Installation view of THE TWO SISTERS by Susan Philipsz at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Installation view of GIRL TALK by Wu Tsang at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

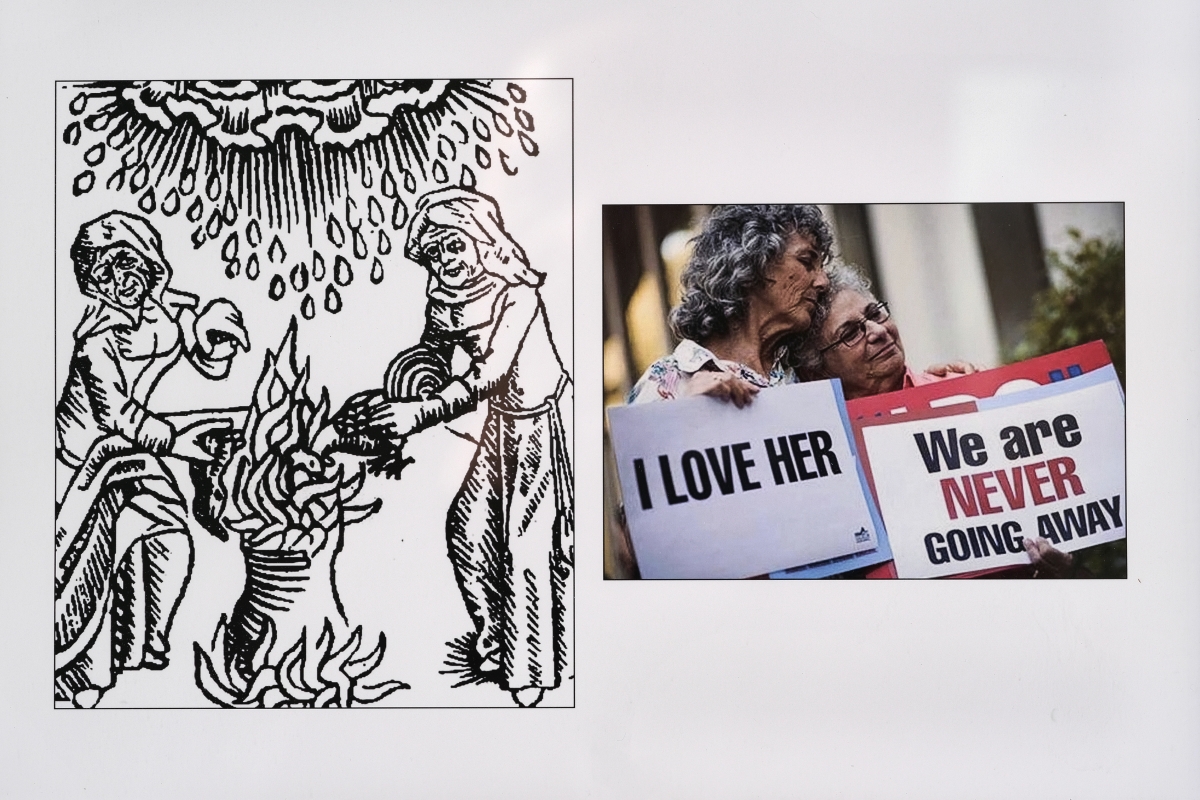

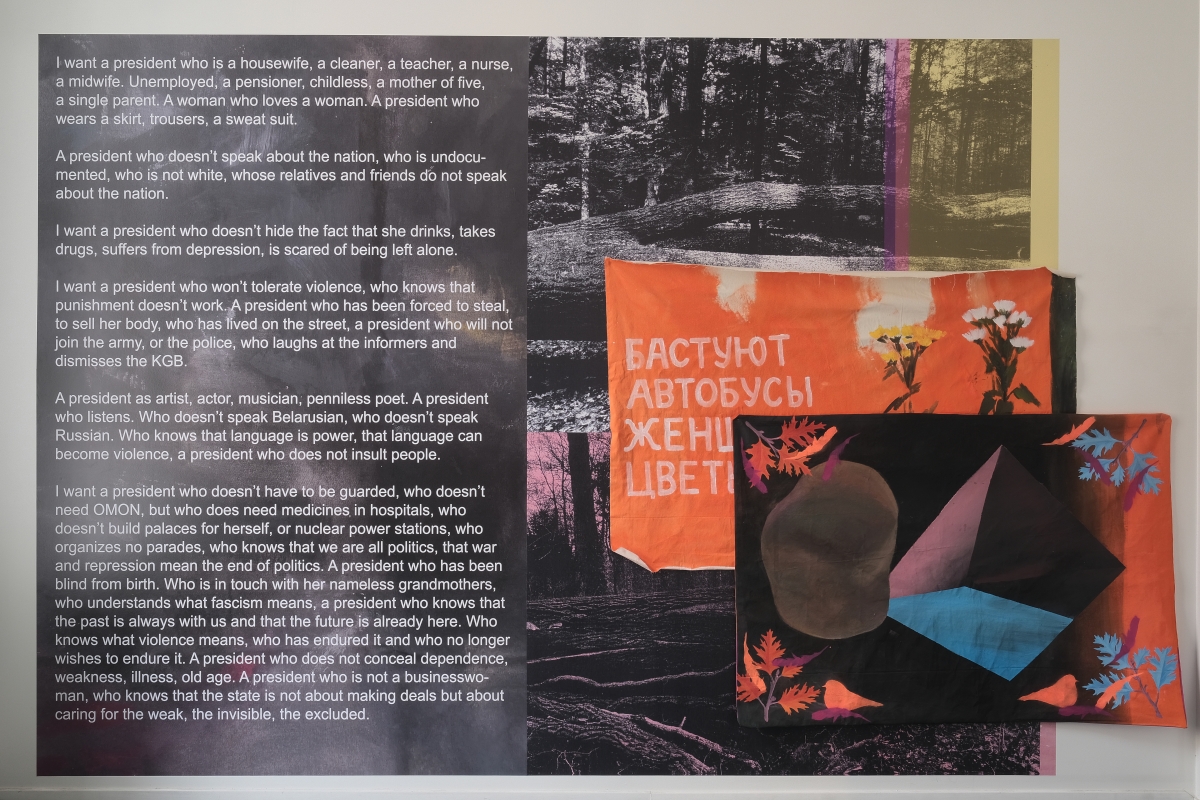

The art by Sanja Iveković has likewise attracted my attention ever since dOCUMENTA (13). A sort of a dainty retrospective of hers was on show in ‘The Little Bird’. It started with a 1976 performance held in authoritarian Yugoslavia. In a photograph from Opening, the artist is standing with her mouth taped shut … Meanwhile, Isn’t She Too Old for This? (2013), the last one of Iveković’s works presented here, brings me back to the question of the quality of an artwork in the non-formalism sense. The small-scale images depicting historical witch hunts, coupled with images from present-day crackdowns on women’s rights activists, the best-known of the latter probably being the members of the Russian group Pussy Riot, are reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s constellations, bestowing a new meaning on a historical image and operating as a test of today’s truth.[5] (It is therefore also a test of our, the audience’s, truth.) In this day and age, when we think, for example, about the self-styled and/or ‘unanimously’ elected Belarusian, Russian, and, by this time probably, Chinese leaders as well, we are inclined to assent and give a big hand to the message of Marina Naprushkina’s seemingly formulaic work I Want a President (2021): ‘I want a president who is a housewife, a cleaner, a teacher, a nurse, a midwife. Unemployed, a pensioner, childless, a mother of five, a single parent. A woman who loves a woman. A president who wears a skirt, trousers, a sweat suit.’ (And this is only the first of a total of six paragraphs …) Of course, the political message expressed by this work is much more far-reaching, urging us to reexamine the role of the head of state in the spirit of radical anarcha-feminism.

Installation view of *ARTWORK TITLE* by Sanja Ivekovič at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

I have mentioned these artworks in a haphazard fashion here, as each of them, even when the basic idea is transparent enough, would require a thorough analysis, and, similarly, their reception requires time. For example, the room filled with grain makes us think about the cargo stuck in Ukrainian ports. Turning my eyes to Ansis Epners’ video image (I presume it constitutes a single work together with the installation, even though the catalogue only refers to ‘video’), I can initially make out only rather nondescript colourful patterns set against a white background. However, these slowly morph into a woman’s kerchief, and in turn, the altar of the humble Old Believers’ church in Maslova, which survived the Soviet era in Latgale, is slowly revealed behind it, subsequently giving way to the grain-filled entrance and the similarly humble exterior with used agricultural machinery in the foreground. The flow of images seems enough, but I nevertheless put the headphones on, and after a few moments of silent humming, a female voice starts chanting a religious song. A phrase I recall, ‘… the power of your magnificence …’, makes us connect a pair of opposites: what has been announced and seen in the liturgy, and the withdrawal (or looking away?) from the Soviet reality that the religious community undertook. Even though the catalogue refers to ‘the return to the creation of the world, where purity, clarity and simplicity dwell’,[6] the thoughts that the work evokes go against each other. The power of song, the musical impression of which seemed sinful as early as Augustine, can contradict both words and deeds, but it can also serve as a source of weak resistance, as in the term coined by Ewa Majewska and revealed in a number of other works in the exhibition.

Installation view of This is How We Win Wars by Indre Šerpytyte at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

The impact of art does not preclude contradictory reflections or disgust, which we cannot get rid of that easily. The self-portraits of dancing soldiers, which the Lithuanian artist Indrė Šerpytytė found on YouTube and which cover the wall opposite the room’s entrance, stop us from finding a proper viewpoint, and also prove sickening. Even though This is How We Win Wars was made in 2018, it urges us to interpret it in the present-day context. The work’s allure lies in the recognisable music by Steve Reich, and in this setting it makes us think about what Reich said as he disavowed the avant-garde of atonal music that Schoenberg had started: ‘Stockhausen, Berio, and Boulez were portraying in very honest terms what it was like to pick up pieces of a bombed-out continent after World War II. But for some American in 1948 or 1958 or 1968 – in the real context of tail fins, Chuck Berry, and millions of burgers sold – to pretend that instead we’re really going to have the dark-brown Angst of Vienna is a lie, a musical lie …’[7] Reich’s music is thus contrasted with the horrors of war suggested by the soldiers’ masculinely erotic and improvisationally ritualised (the prevailing religion in any state usually supports military aggression) dance gestures. This image/music compound therefore obtains a very pronounced emotional ambiguity, although on closer inspection some of the soldiers’ movements have a gender-neutral and even hybrid character.

The diversity of the spaces and their suitability, or the lack thereof, for specific artworks places additional responsibility on the layout/scenography of the exhibition. It includes not only audio installations but also visual works with an essential sound component. In some locations, as you listen to/look at the work, an alien sound texture can be heard in the background. Comparing our post-visit impressions with the Finnish artist Jaana Kokko, we arrived at the idea that, seeing as voices of silence, poetry, protest and otherness are highlighted here, the audio works could have been housed in larger premises, possibly making use of other floors in the abandoned building.

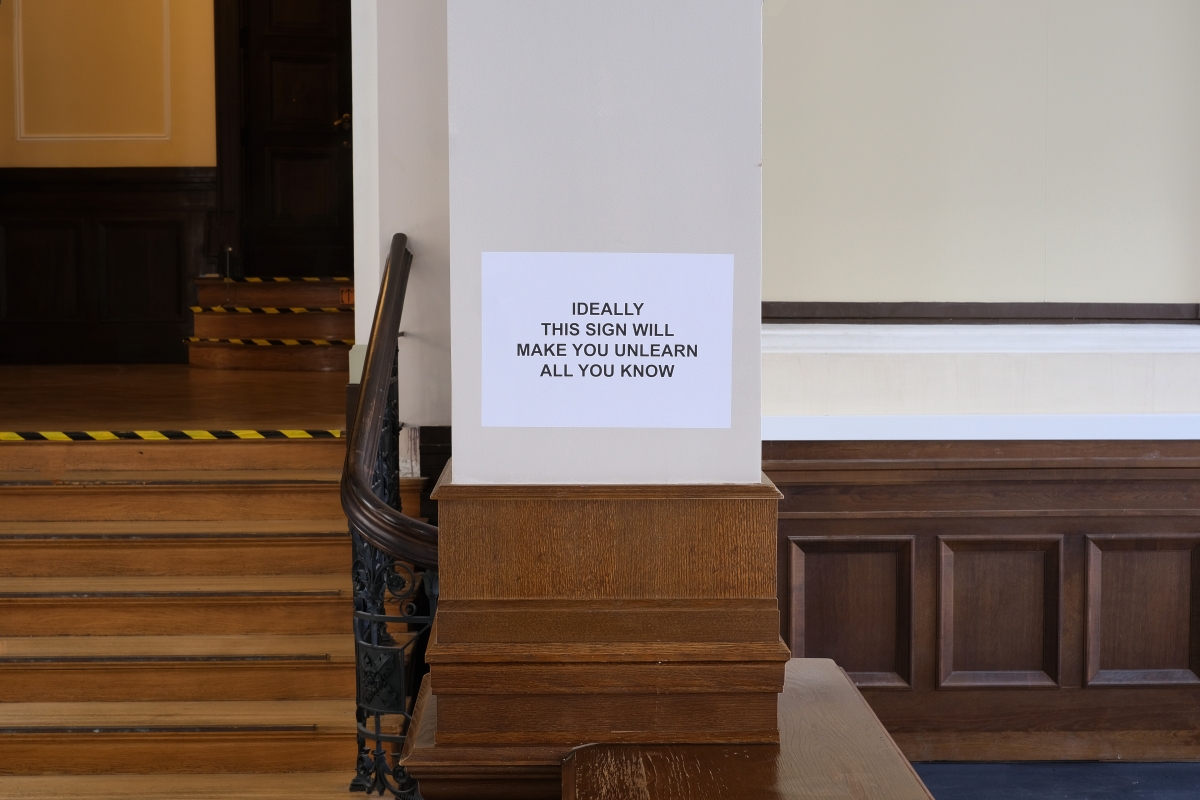

On leaving ‘The Little Bird’, I again saw the notice, in black letters on a white background, saying: ‘This Sign Trespassed Many Frontiers To Be There’. It is part of Laure Prouvost’s Signs (2020), which can be seen or read in a number of locations across the exhibition. We can associate this with the path that Survival Kit has travelled so far, having started back in 2009 when the economic crisis hit. But it can just as well apply to the bodily-emotional and intellectual situation of every single person absorbing art and thinking about the world around us here and now.

Laure Prouvost. Installation view at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022.Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Ansis Epners. Installation view at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Installation view of I Want a President by Marina Naprushkina at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Installation view of *ARTWORK TITLE* by Sanja Ivekovič at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 13 “The Little Bird must be Caught” curated by iLiana Fokianaki, in Riga, September 2022. Photo credit: Ēriks Božis / Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

[1] 104 symphonies (2014).

[2] Bishop C. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London, New York: Verso, 2012, p. 8.

[3] Fokianaki iL. ‘The Little Bird Must be Caught Roaming Free’. In: Bloma E. (ed.). Survival Kit 13: The Little Bird Must be Caught. Contemporary Art Festival (catalogue). Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, 2022, p. 12-15.

[4] Philipsz’s work which was on show in dOCUMENTA 13 made use of Study for Strings (1943), a composition that Pavel Haas, a Czech composer who was born into a Jewish family and died during the Holocaust, wrote in the Terezín concentration camp. The installation was created in order to give an impression of a fragmentary, disarranged piece of music.

[5] See Das Passsagen-Werk (The Arcades Project), K2,3. In Iveković’s installation for dOCUMENTA (13), entitled The Disobedient (The Revolutionaries), Benjamin was represented among these stubborn rebels in the form of a children’s toy donkey.

[6] Vanaga A. ‘Maslova’. In: Bloma E. (ed.). Survival Kit 13: The Little Bird Must be Caught. Contemporary Art Festival (catalogue). Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, 2022, p. 32-33.

[7] Ross A. The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007, p. 475.