Martynas Kazimierėnas (b. 1982, Lithuania) is an object designer and artistic director at the March Design Studio in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied design at Vilnius Academy of Art, and later continued his studies at Eindhoven’s Design Academy. Functionality, materiality, technology, light, mood and experience are the key words in this conversation with Martynas.

Viltė Visockaitė: Where does the development of a design object begin? What comes first: content or form? How do you choose the right materials for a design object?

Martynas Kazimierėnas: I start with ideas. I prefer the principle of creating an object as a scenario, a strategy, rather than making intuitive decisions that are difficult to explain. I’m interested in technologies that are evolving now and materials that could reflect today. The form is determined by the concept. Why and what that concept is is the most interesting part of the work.

VV: In 2012, you founded the March design studio, which has received a lot of attention in Lithuania and abroad. How does this work differ from your individual design practice? Do you have to compromise and think more about the customer?

MK: There are a lot of clear criteria for things that will be sold in shops, and they have to be met. For example, simple production processes, a low price, low investment, the trendiness of the item. It is important that it looks innovative but isn’t too new to scare away conservative consumers. And above all, it has to be better than the other one. It may sound like a daunting rebus, but it’s easy enough to work with because the requirements are clear.

In my personal practice, there are almost no criteria or rules. There are many scenarios at work. When I was doing my first piece, I was talking to the gallery director, and somehow I tried to ask her what kind of piece they needed, and she got lost, she didn’t really understand the question :).

VV: The aesthetics of everyday life confusion, I thought when I looked at some of your work (whether it’s the tangled wires in Personal Sunset 2.0, the postal information in Shipping Shade, or the crumpled fabric in Table Cloth).

MK: There is a hidden tangle of wires in every light fitting, mail packages that have been damaged on trips, and tablecloths that aren’t ironed. These things aren’t different; they just don’t try to look better than they are. I often want to learn something from them myself.

Personal Sunset 2.0. Photo: petrulaitis.lt

Shipping Shade. Photo: petrulaitis.lt

VV: Tell us more about one of your works that was caught in the fog of illegality. In what context was it created? The commissioner probably cannot be revealed. 😈

MK: I don’t know the commissioner, but I know who might know him. I undertook the project because moonshine has always been bottled in obscure containers, jars or plastic bottles that discredit its high quality and spoil the consumer’s experience. Almost none of the information that usually appears on the packaging could be disclosed in this case. It was an opportunity to make a very laconic and concrete design.

By the way, edition 2023 is bottled in recycled, previously stolen bottles. This is the ultra-circular economy: recycling that starts before the product is sold.

0.7. Photo: petrulaitis.lt

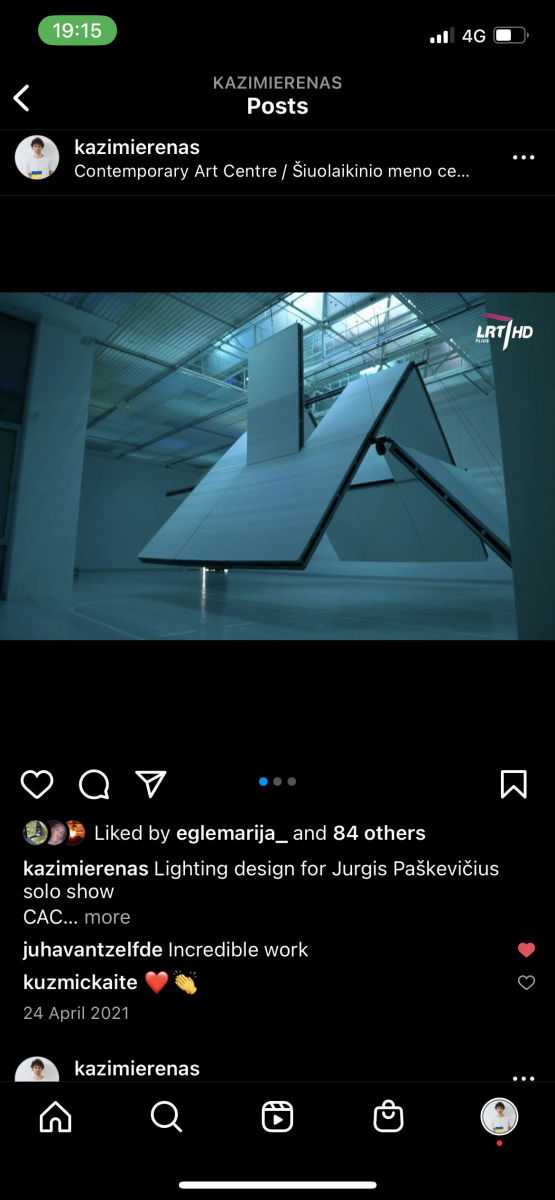

VV: You have recently been contributing to other artistic projects as a light artist. You worked on Jurgis Paškevičius’ exhibition Alternating Current (2021) at the Contemporary Art Centre, Antanas Lučiūnas’ performance Sunrise (2022) at the White Bridge SkatePark in Vilnius, and the Lithuanian Pavilion represented by Robertas Narkus’ project ‘Gut Feeling’ (2022) at the Venice Biennial. What do you rely on when thinking about light in such projects? How does it change/create the experience of the artwork and the space?

MK: If you work with a performer, the light is an important part of the performance. It’s a powerful tool, so the work is sensitive, it’s not only about how to show the performer or reveal the work, but also to bear in mind where it’s being shown and who the viewer is.

If you work with space, then the work is more like a post-production. The space can be revealed, disguised or modified into another, creating a feeling and emphasising its different parts. Or simply to make the exhibited artwork look better. Sometimes the viewer won’t even notice the lighting decisions, but they will have an impact on the overall image.

Either way, it’s important to empathise with the work and understand the artist you are working with.

Jurgis Paškevičius’ exhibition Alternating Current (2021) at the Contemporary Art Centre

Antanas Lučiūnas’ performance Sunrise (2022) at the White Bridge Skate Park in Vilnius

Antanas Lučiūnas’ performance Sunrise (2022) at the White Bridge Skate Park in Vilnius

Lithuanian Pavilion represented by Robertas Narkus’ project ‘Gut Feeling’ (2022) at the Venice Biennial

Performance by Silvana. Lithuanian Pavilion represented by Robertas Narkus’ project ‘Gut Feeling’ (2022) at the Venice Biennial

VV: How does this practice overlap with design development? Light is also important in your design objects, such as Personal Sunset 1.0, Personal Sunset 2.0 and the flashing light on the roof of Radio Vilnius. By the way, how did it end up there?

MK: The appearance of the lamps I make is less important to me than the character of the light they emit and the mood they create. Practising at events allows me to explore the possibilities. Often experiments with spaces lead to solutions for objects, and vice versa.

Radio Vilnius works in a small kiosk and has a big influence on the music culture of Vilnius, so I wanted to highlight it. We built an antenna bigger than the kiosk, and put a slowly flashing light on it. It was the kind of light that the Civil Aviation Regulations say should be used to mark radio antennas over forty-five metres high.

RadioVilnius

VV: What is your relationship with time: past, present and future? For example, in Blow (2021), as a starting point, you chose a ceiling fan that has almost disappeared. Is this a kind of nostalgia?

MK: It certainly is. As technology evolves, we often lose beautiful things. This is my attempt to bring back an almost extinct object. Deconstructing it, leaving only the emotionally impactful parts.

While working on this project, I realised how movement fits into our spaces, which often resemble photographs taken with delayed shutter release.