Gut House on the Print Level, exhibition by Evita Vasiļjeva, installation view, kim?, 2016. Photography: Ansis Starks

When thinking about the new series of exhibitions at the ‘kim?’ contemporary art centre,[1] which opened on 26 October, and, more broadly, about the current situation with art, the following words came to mind: “The gods have left.” Actually, it would be more precise to say “The gods have picked up their coats and left…”, because this thought came to mind on recalling the coat hangers resembling human corpses in Jānis Dzirnieks’ exhibition-installation. The statement on its own is quite trivial: something similar was expressed by Hegel in his lectures on aesthetics regarding the permissiveness of the content of art, and this diagnosis suits the 19th and 20th centuries as well as it does the 21st century. (I should add that some artists working today have not noticed the departure of the gods; however, their work does not count as contemporary art, and would most likely not be found in the exhibition space at ‘kim?’.) But the exhibitions of work by Evita Vasiļjeva, Ojārs Pētersons, Krišs Salmanis and Jānis Dzirnieks all confirm ‘the departure of the gods’ in some special way, perhaps because they are all put next to each other.

Texts (explanatory notes?) accompany the guide to the layout of the exhibitions; as I read them, I recognise excerpts from a conversation that took place nearby, a few weeks before the exhibitions opened. It was in an empty space on the other side of the courtyard, a space in which Vasiļjeva had a studio for a time. In the published version of the conversation, however, the speakers include Epicurus and other strange characters, but at least Epicurus fits my theme. Let us remember his conclusion that the blissful gods do not bother to care for humans (see Letter to Menoeceus, 123–124), and so we can say that the gods were and are absent and indifferent (also with regard to aesthetic permissiveness), both for the ancient Epicureans and for us today.

The exhibitions let us think in broader categories of time. For example, Vasiļjeva’s works are a testimony to the battle regarding sculpture as a tradition creating spatial objects in the ‘age of mechanical post-reproduction’. The very instruments of reproduction are turned back into sculptural objects; strange creations hang from the ‘black paintings’ like insides turned outwards, until finally I step inside… and the artist quietly touches my shoulder and says: “You’ve climbed into the work of art.” The red colouring on the floor is not an attempt to make the light-grey concrete areas of the floor less conspicuous; instead, it is her work with consciously dissolved boundaries between it and the surrounding environment. Confused, I mutter something about Carl Andre and his artwork, which I once stepped on and tripped over at an exhibition…

Vasiļjeva’s work is serious, and I do not mean this as criticism.[2] ‘Seriousness’ can also be understood as a lack of reflective distance, or irony that might otherwise allow us to observe the chosen means of expression from afar: there are too many of them in Dzirnieks’ installation (including the tribute to “the aesthetics of the metaphysics of indefinite intimations”[3]). If we’re looking for irony, the origins of which, by the way, are also found in the Ancient world, then we need to look in the direction of Salmanis and Pētersons. I use ‘Salmanis’ metonymically, because I actually mean his artwork, to which I somehow automatically attach an element of the meaning of irony. Pētersons, for his part, is witty whenever and wherever we meet, with no need for metonymy. But his artwork… that’s a slightly more complicated issue.

Waiting for the Next Minute, exhibition by Jānis Dzirnieks, installation view, kim?, 2016. Photography: Ansis Starks

second hand, exhibition by Ojārs Pētersons, installation view, kim?, 2016. Photography: Ansis Starks

I did not plan to write about Pētersons, because I’ve already done that before. However, having heard Ieva Lejasmeijere’s exhibition reviewed on the radio show Pasāžas (aired on Latvijas Radio 3, and likewise ironically refined, including the intonation of the radio host’s voice), which this time examined ‘nothing’ (and also the ‘nothing’ of the text accompanying the exhibition), I decided to make one remark of a linguistic nature. Of course, both the mirrors, which reflect only an empty glass cylinder with a dome-like cover in an empty room, and the water pitcher labelled, as I originally read it, ‘aqua’, create a feeling of emptiness, like what emanates from senseless tautologies. However, the labels on the pitchers in the photographs and those drawn on the walls read ‘AGUA’ instead of the Latin ‘AQUA’. This Latinised spelling could be allowed in some languages (as it is in Spanish and Portuguese), but, remaining as we are in the horizon of Ancient culture[4] (maybe I should write ‘in the horizon of forgetting’?), I perceived it as a small (Kharmsistic) linguistic deformation.

In paraphrasing it as a question about truth, one could say that Pētersons’ exhibition entitled Second Hand is not about ‘nothing’. Instead, it is about how and to what extent a small deviation in an image or a small mistake in a text changes the truth value of the message. This is, of course, just a marker for a potential direction of interpretation; and therefore I can still say that I have held fast to my decision not to write about O.P.

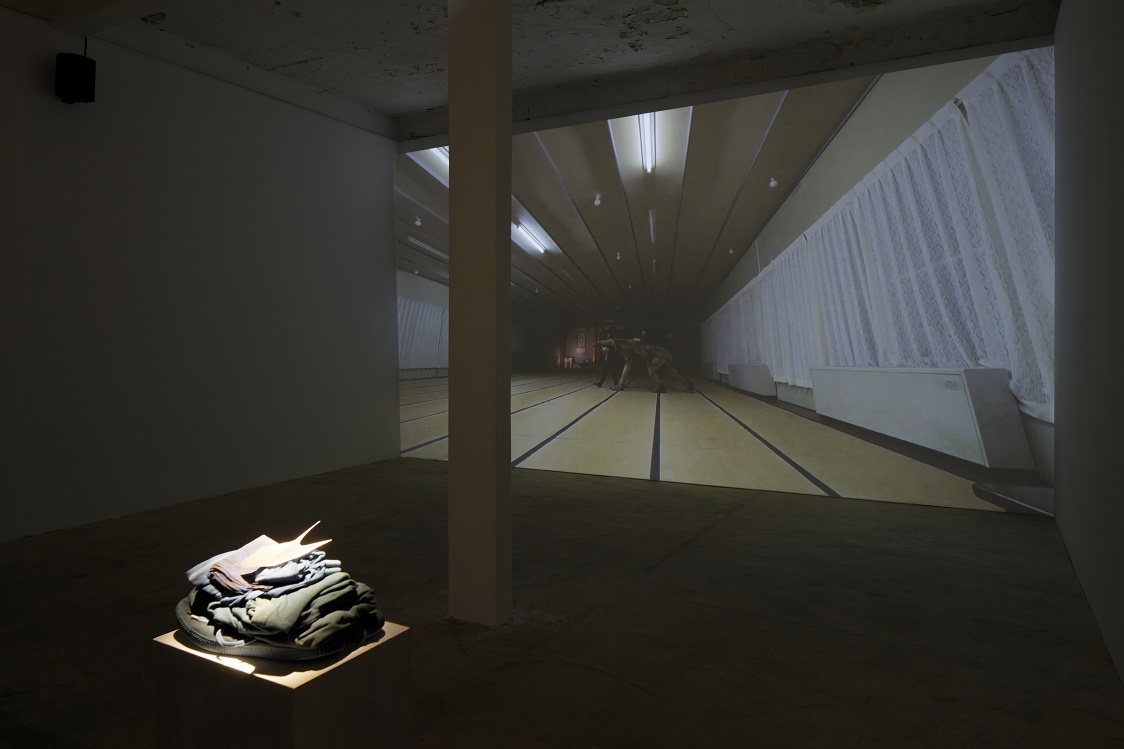

Actually, I wanted to write about Salmanis’ video work Skilando, which, due to the small pile of clothing with a poem written on a slip of paper and pinned to the top, can, purely formally, also be called a video installation. Unlike other works by the same artist, this one seems completely traditional (‘been there, done that,’ ‘something similar has already been seen’).

First, regarding the meanings of ‘been’ and ‘seen’. The camera slowly pans across a half-abandoned Japanese building, as if one of the external walls has been removed, or rather, showing a cross-section and revealing a series of spaces, the mood of which recalls Tarkovsky’s films, at least for a person with Soviet-era, albeit non-standard, visual experience. (The ‘mood reference point’, if I may call it that, can be different, but that is of no relevance in this case.) As Robert Smithson wrote: “Some artists see an infinite number of movies.”[5] But that is more a comment on the meaning of a work of art than the artist’s experience.

The low position of the camera, like viewpoints in some paintings by Mary Cassatt; the unexpected images of random objects in a former skiing resort, as in Katrīna Neiburga’s video-installation Solitude from 2005; the gradual and irregular lighting of daylight bulbs, which brings to mind Salmanis’ own work in the exhibition Time Pit (2011) together with Daiga Krūze, where the lighting of areas of the ceiling followed, I believe, Mendeleev’s Periodic Table, although here it’s the technology of desolation.

Skilando, exhibition by Krišs Salmanis, installation view, kim?, 2016. Photography: Ansis Starks

A furry, three-legged animal wanders through all the regular junk represented in contemporary art that we see in the video, which takes up the entire wall (in this case, it’s a successful solution), and includes, among other things, a Coke machine and a Disney teddy bear in an empty child’s playroom (I find it difficult to call it Winnie the Pooh, because the unforgettable character and voice of the ‘silly old Bear’ from the Russian cartoon dominates in my memory). Just as in Robert Walser’s The Walk, the sequence might be different, but in both cases, Salmanis’ and Walser’s, the chosen sequence seems quite convincing. The strange animal’s ritualised movements, like those of a giant puppet, are dictated by two actors dressed in black. Their faces are also covered, which in some frames allows the puppet (animal) to merge with the dark background and exude a light effect of horror.[6]

This character immediately mesmerises me, because it makes me remember my favourite childhood book On the Track of Unknown Animals, a book that my grandmother rescued from the stove of a neighbour of hers, an old communist woman.[7] In terms of proportions, Salmanis’ ‘animal’ most resembles the ‘maned wolf’, as it is called in the above-mentioned book by Heuvelmans, and which can now also be found in Riga Zoo. But the milodon (almost no resemblance), described by Heuvelmans and drawn by a Russian illustrator, also comes to mind, an animal I so very much wanted to see in the real world, along with other mysterious creatures.

So much for the meanings of ‘been’ and ‘seen’. What’s new here? A rejection of paradoxicality and a surrender to the seduction of desolation, in other words, routine variations of marginality? But that would be something new only in the context of Salmanis’ other work. Is that not fleeing to the possible world that has already been tested in the language of art for some time?

Roald Dahl’s children’s book about little Matilda contains an awful character, Miss Trunchbull, the school headmistress. When a girl from the older grades scares little Matilda and her friend with horror stories about the headmistress, we think she is exaggerating on purpose, joking with the girls. But when Miss Trunchbull then grabs another little girl by the hair and flings her across the yard, as one would in a hammer-throwing contest, we think Dahl himself is exaggerating in his construction of the possible world of the book, in which the older girl’s stories are true. But while reading, we have forgotten that reality is often much more horrible than fiction. If such forgetfulness is allowed in children’s books (in Dahl’s book, however, it is more like a warning), then one must ask whether that is the (true, right) path of art (language-game).

And still, whether speaking in terms of visual variety or horror, or the cruelty of humans, art cannot outdo reality (including in this concept our daily delving into the virtual reality offered by the digital media). What is one to do?[8] At the end of my second visit to the exhibitions at ‘kim?’, I head to the restroom, where the graffiti on the wall, in the form of a series of comments, still dates from the days when this was a canteen:

Don’t Eat Anything You Aren’t Prepared to Kill.

Don’t Kill Anything You Aren’t Prepared to Eat.

Don’t Kill.

Don’t Eat.

And under that, the last word to date, in bold black lettering:

Fuck Vegetarians – ‘All Gods Are Carnivorous’ –…

Photo documentation from the exhibitions at kim? Contemporary Art Centre:

Ojārs Pētersons and Krišs Salmanis

Evita Vasiļjeva and Jānis Dzirnieks

[1] The exhibitions really are parallel to each other, and to a large part independent exhibition-installations, instead of a single exhibition organised by several artists. Their unifying factors would be the more or less monotone sounds and … the absence of the gods.

[2] Seriousness here does not rule out a game, fragmentation and ambiguity, all of which we already see in the name of the exhibition, Gut House on the Print Level, which has been ‘translated’ into Latvian as ‘Halfway Pink’.

[3] A trend in contemporary art based on an (unconscious) merging of British empiricism and Platonism. Specifically, only personally understandable intimations, feelings and so on are granted the seriousness of Platonic ideas; in other words, chance aspires to become necessity. (These lines can be perceived as irony about the author of this article, Plato, individual artists, etc.)

[4] The blue and white of the water pitcher also point in the direction of Greece, and, consequently, the Ancient world.

[5] Entropy and the New Monuments, 1966.

[6] Don Quixote would consider it real, as in the case with Master Pedro’s puppet show (see Chapter XXVI of Part Two).

[7] In 2011, while preparing a lecture in conjunction with the Swedish artist Ida Pettersson’s exhibition at ‘kim?’, which included the theme of the mythical Vegetable Lamb, I found this book, translated from Russian, although originally written in French by Bernard Heuvelmans, known as the father of cryptozoology.

[8] The continuation is fictional, and taken from a novel by Margaret Atwood.