In the winter sleet, or the summer heat that melts asphalt, museum spaces with stable temperatures create the illusion of art unaffected by time (or climate change). This illusion is reinforced by paintings done in the manner of the Old Masters, making it seem at first glance that the works of Žygimantas Augustinas are made for museums. His exhibition ‘Guarantee’, on show at the Vilnius Picture Gallery of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art, can be described as a retrospective, showcasing most of his work from the earliest graphic pieces to current projects. The retrospective format also references the sum of completed works that can be reviewed, discussed and recognised for their merits and timeless values.

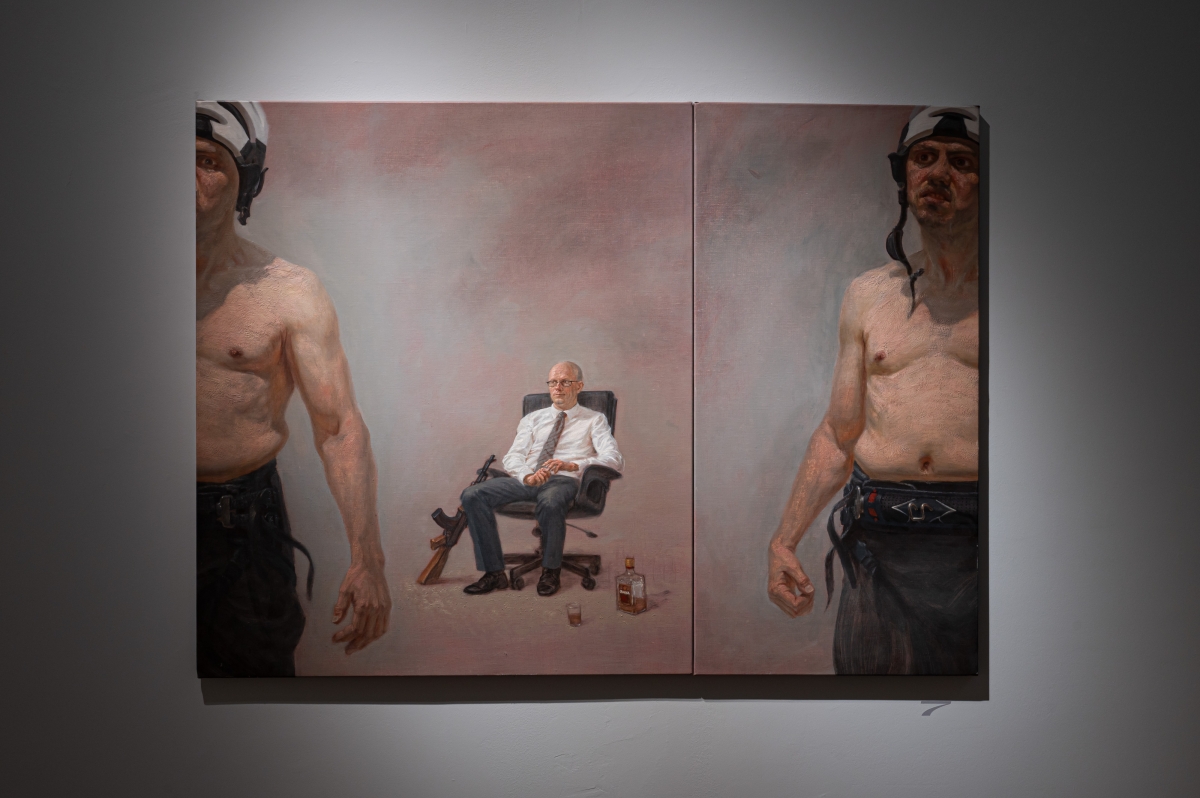

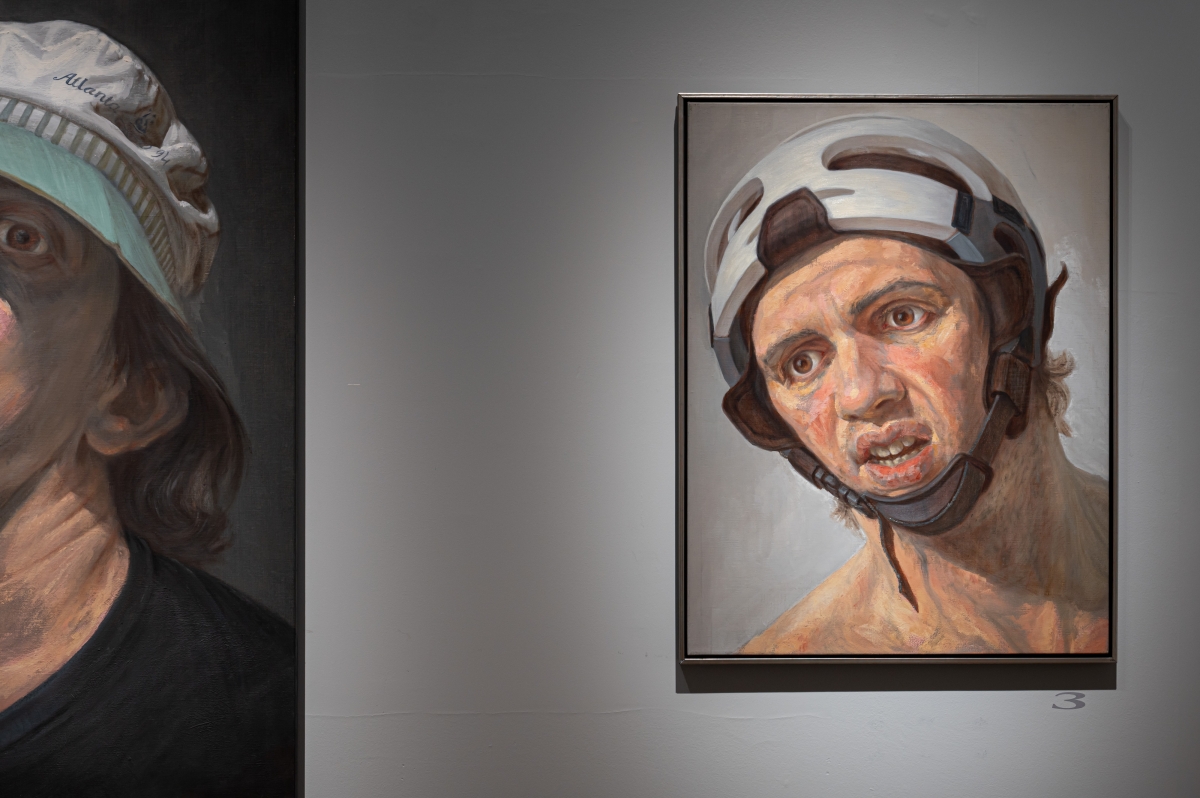

However, Žygimantas Augustinas is a contemporary artist, and his ‘museumness’ is simply material for crafting narratives, much like his own figure, which is used in place of the protagonist. In Birutė Pankūnaitė’s article ‘Prostheses, Good Intentions, Hybrids, and a Lullaby’ (7 Meno Dienos, No 24 [1516], 14 June 2024), she highlights the hysterical masculinity that Augustinas perceives as a prosthesis and reflects in many of his own or other men’s images. ‘Exaggerated facial expressions, typical self-loving poses, repulsive pride in one’s superiority, stereotypical costumed appearances, or unappealing yet emphasised nudity: many paintings pulsate with the unhealthy narcissism of the character.’ This interpretation aligns with the message the artist seems to be sending.

In the introduction to the guide to his exhibition ‘Guarantee’, Žygimantas Augustinas outlines a completely different narrative created by the exhibition curator Akvilė Anglickaitė. He presents concepts and terms that serve as keys to individual rooms and the artworks in them. The main concept of the narrative is reality and its instability. ‘A vanishing reality,’ says Augustinas, one in which nothing is clear or tangible, crumbling and increasingly fracturing with each subsequent work. It is normal for a good artist’s work to offer multiple viewpoints. This temptation arose for me while writing this article: choosing a particular basic concept on which the article’s architecture is built can differ entirely from one based on another concept also suitable for this exhibition. During the pandemic, the stark contrast between reality and actuality became so pronounced and unacceptable that I started reading Kristupas Sabolius’ edited book ‘On Reality’ (Lapas, 2021) every day. Its blurb states that reality is not self-evident. The war in Ukraine also contributed to its fracturing, which Žygimantas notes by devoting a separate room to this theme, with the central piece One Month Since the Start of the War (2022).

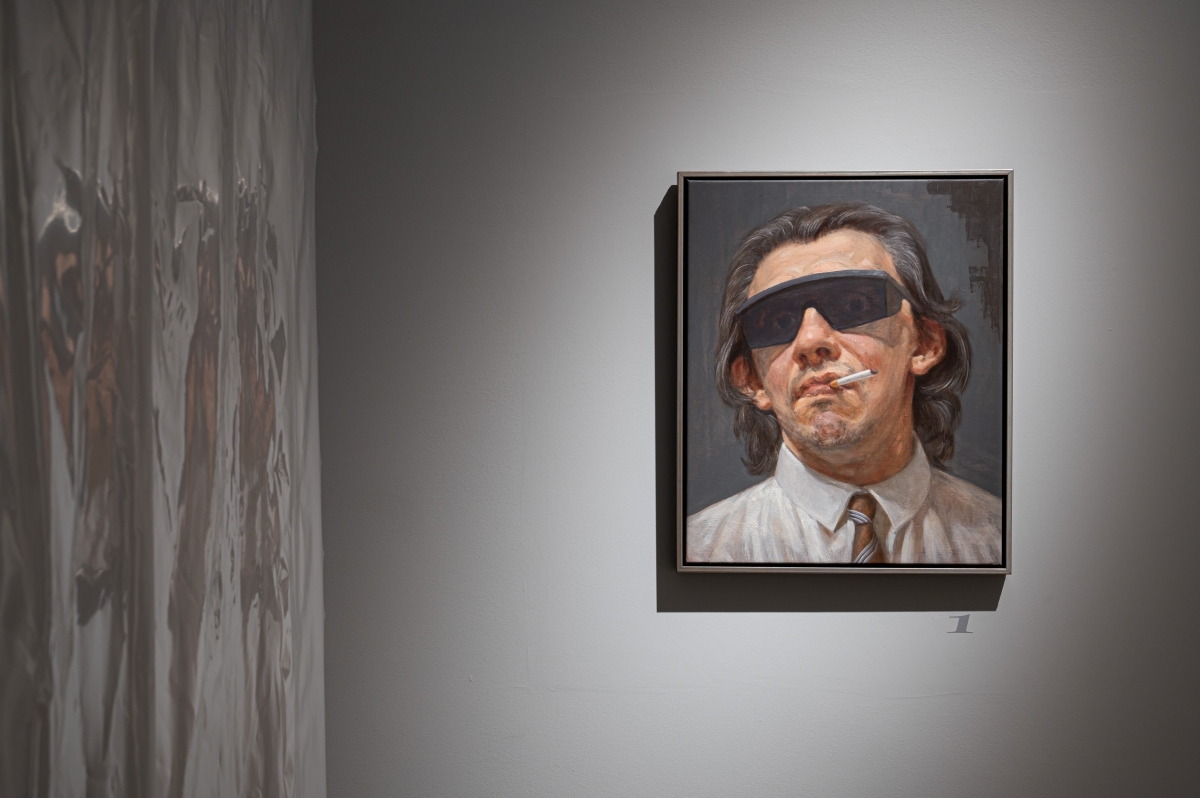

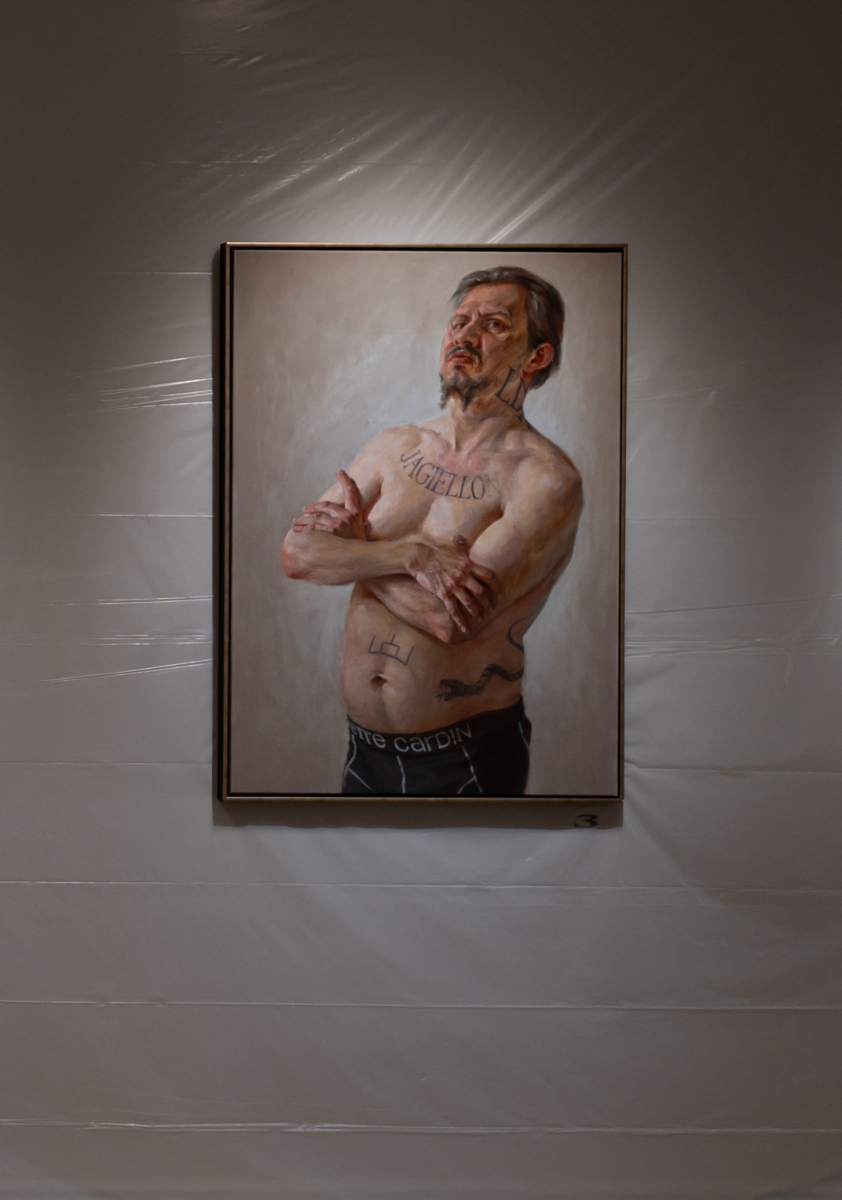

Jagiellon. 2020. Oil on canvas, 114×81 cm. Photo: Gintarė Gritėnaitė

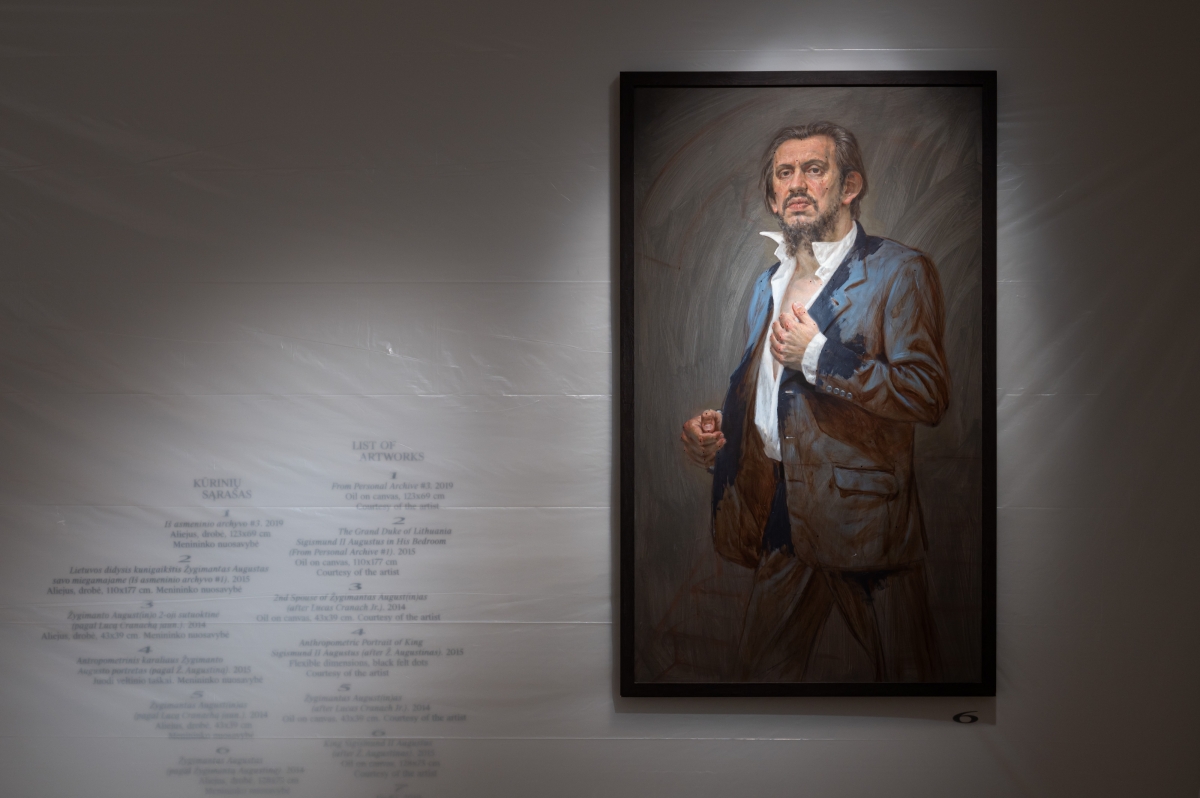

However, I would prefer to build on different material, less discussed by both the curator and the art critic mentioned. The unhealthy narcissism of the characters depicted and the sarcasm towards them raise questions about the artist’s relationship with his characters, or possibly himself, as the depicted figures bear a clear resemblance to the artist. There is also a play on the similarity between the names Sigismund II Augustus (in Lithuanian Žygimantas Augustas) and the artist’s name Žygimantas Augustinas, further highlighting the connections with the characters depicted, in works such as Žygimantas August(in)as (after Lucas Cranach Jr.) (2014). In the works, there is the protagonist’s enjoyment of power, sometimes even the violent egocentrism of the white man, as in the portrait with a gun Respite (2012), or Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund II Augustus in His Bedroom (2015), with a threatening clenched fist. Initially, I thought he was wearing a karate outfit, but it was just a robe. We see a company executive or a businessman, probably after a night out drinking, with his shirt unbuttoned and stains on his jacket, a ‘nouveau Lithuanian’, ‘nouveau Russian’, or nouveau Sigismund II Augustus (King Sigismund Augustus (after to Ž. Augustinas), 2015), feeling the reflections of the cult of genius (The Case of K. Donelaitis, 2014, although this work is not exhibited in the show). All this is mixed with a large dose of caricature, irony, and the yeast of laughter. The proportions are maintained, and the master’s hand turns even the strangest combinations into great recipes, worthy of Queen Bona’s recipe book.

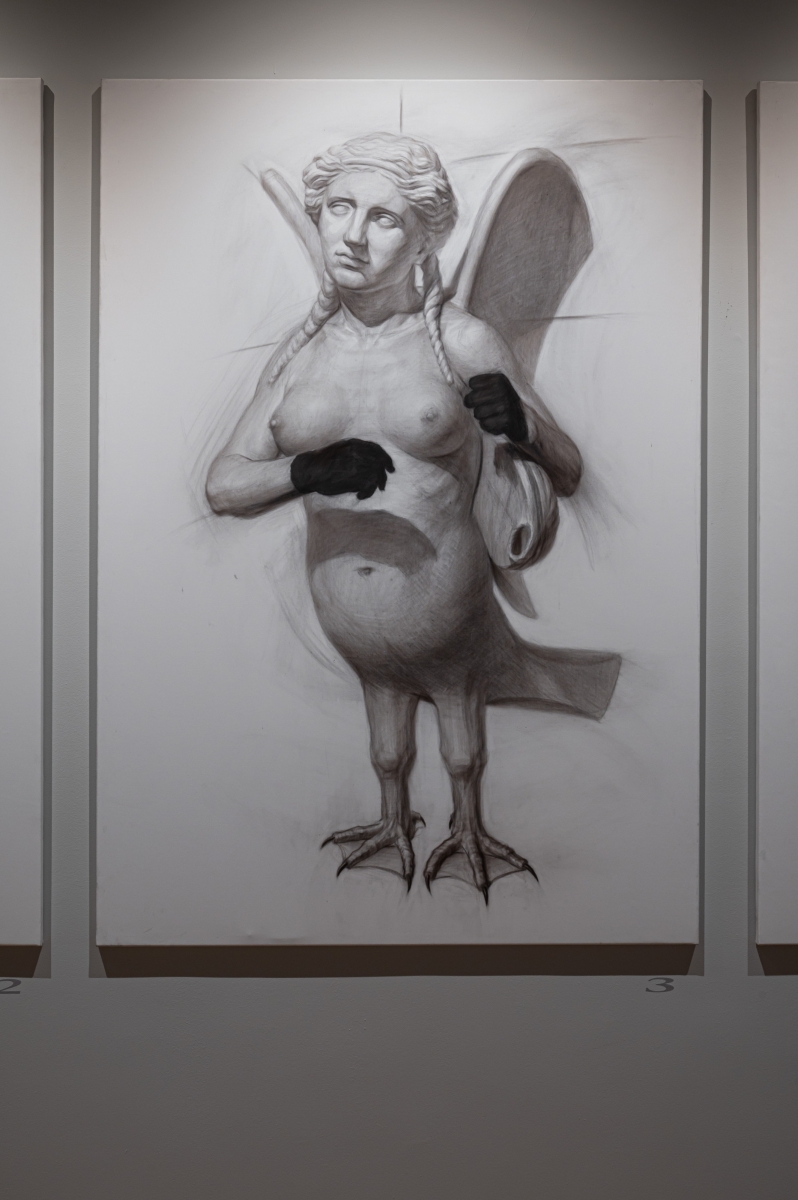

The magic enchants us so deeply that you forget what you were laughing at. First and foremost, it seems that the artist is laughing at himself, i.e. he uses himself as a model, because it would be unethical to mock others so harshly. (Saying that he uses himself instead of a model because it is more convenient is unconvincing; looking at oneself is much more challenging than looking at what is directly in front.) Thus, this laughter, merging the artist’s ‘self’ with his characters, persists even in his recent project, seirenes (male sirens) with animated genitalia (Siren #3, 2023), akin to other Greek gods who did not shy away from sex, not only with other women but also with natural phenomena or objects (for instance, Zeus pursued the goddess Cybele, who changed into a rock to escape, but was raped even in that form). According to Greek mythology, you can never be sure that a bull or a swan isn’t a transformed rapist god. The exhibition’s title points to the danger of relying on the perceived (or imagined) reality for assurance and trust. It is inspired by one of the three maxims inscribed on the façade of the Temple of Delphi: alongside the well-known ‘Know thyself’ and the less famous ‘Nothing in excess’, there was a third, whose meaning has been debated for thousands of years, clearly linking certainty (assurance) with misfortune.

Thus, the artist views reality through the prism of sarcasm and laughter. Many renowned philosophers have pondered not only reality but also laughter. Immanuel Kant’s famous version of incongruity theory states that the essence of humour is ‘the sudden transformation of a strained expectation into nothing’. Therefore, the ironic title of the exhibition ‘Guarantee’ can be linked not only to the Greeks but also to Kant’s incongruity theory, which speaks of the transformation of expectation/guarantee into nothing. Schopenhauer claimed that humour arises from the sudden discrepancy between the representation of an object and the recognition of its true nature. This fits painting, where the intelligent PhD in fine arts Žygimantas Augustinas is portrayed as a failure and a fool (Self-Portrait #2, 2004) or as an ‘uppity’ inadequate ruler in fashionable branded underwear (Jagiellon, 2020).

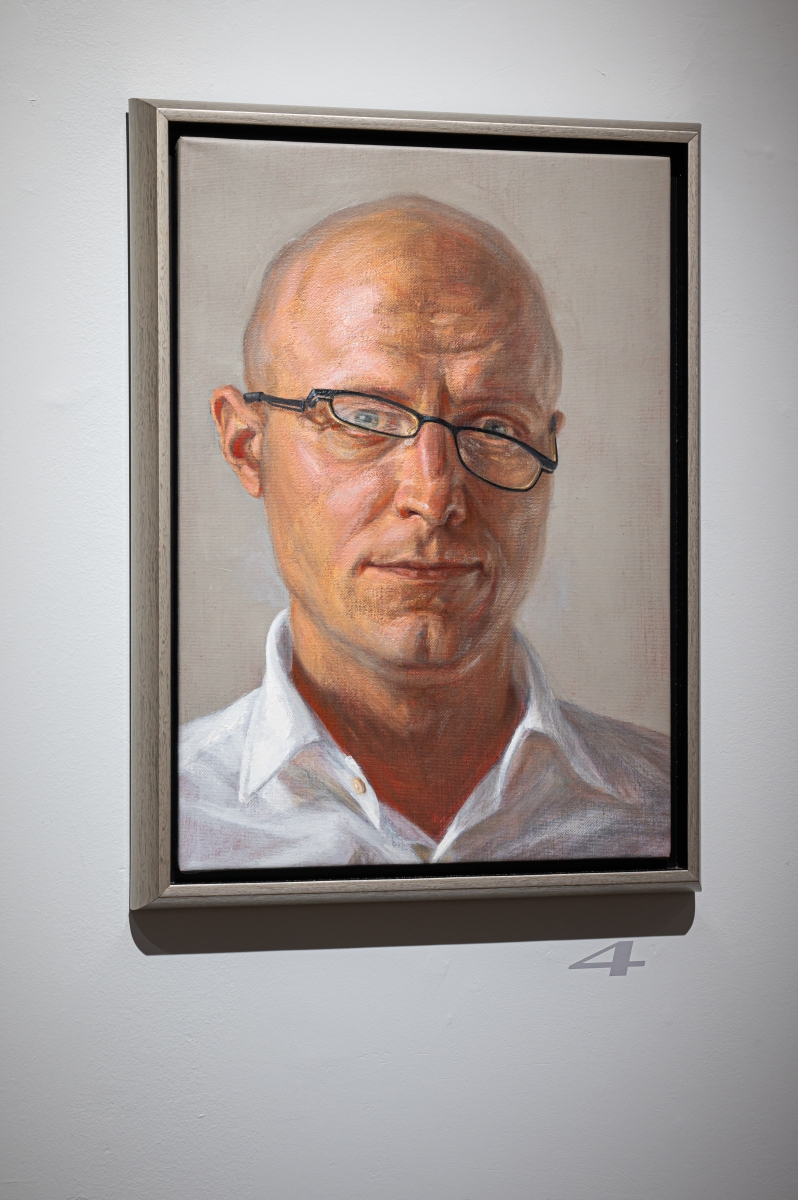

Self-portrait #2. 2004. Oil on canvas, 40.6×40.6 cm. Photo: Gintarė Gritėnaitė

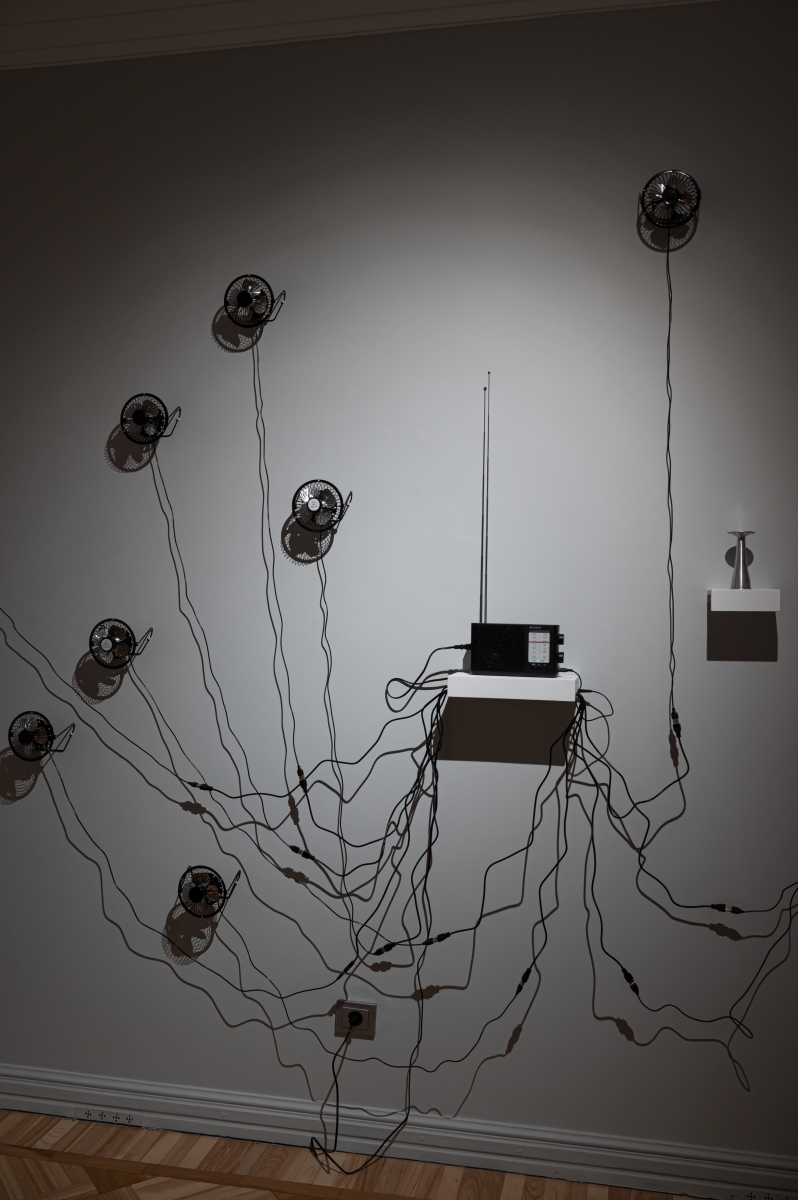

This discrepancy between the portrayal of an object and its true nature (in this case, the artist’s personality) is discussed extensively in Henri Bergson’s book Laughter, which devotes significant attention to the idea of disguise: ‘The person who disguises themselves is comical […] Similarly, any disguise, not only of a person but also of society or even nature, becomes comedic.’ Bergson emphasises the social significance of laughter, describing it as a social gesture. This concept seems to drive the artist’s creative carousel, including his recent sound projects that reflect the threats of war (Image and Sound as Tools for Controlling and Relaxing the Humans Psyche, 2022–2024). Admittedly, these recent works contain much less humour and laughter, whereas earlier pieces, such as Sigismund II Augustus with Barbara Radziwiłł (Žygimantas August(in)as’ Second Wife (after Lucas Cranach Jr.), 2014), or Donelaitis, are probably only relevant to our social circle. Such jokes would hardly be understood by a New Yorker. The social significance here unfolds as broader social criticism, and in Bergson’s words, the artist’s ‘comedy creates characters we have met and will meet on our path’. According to the philosopher, while characters in drama are individualised, those in comedy are typified, representing specific groups of people. Sigismund II Augustus and Barbara Radziwiłł are essentially legendary rulers, Dalia Grybauskaitė is a president, and Bona Sforza is a queen (The Phantom Portrait of the Hybrid of Queen Bona Sforza and Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė, 2017). Although not in the exhibition, the collection includes a civil servant (A Clerk, 2012), possibly a hired assassin (Executor, 2011), a witness (Crime Witness, 2002–2003), and even sirens, which represent a certain group. According to Bergson, many comedies are named in the plural form, or by collective terms. ‘Learned Women, The Ridiculous Précieuses, The World of Boredom, and others depict numerous encounters with different characters who, in reality, belong to the same type.’ The philosopher notes that a comedic character is a type that essentially relies on models that brazenly clash with societal norms. It goes without saying that Žygimantas presents us with a gallery of heroes who break or do not conform to these societal safety standards.

Bergson also emphasises the aspect of the body and corporeality (including the body of society), which is so prevalent in the artist’s work. The philosopher draws attention to the comedy of the ‘dull, monotonous body’ and the characters obstructed by their own physicality. Žygimantas’ characters constantly and proudly display their often unattractive bodies. This creates a contrast between the Classical painting technique, which suggests the importance of the depicted subject, and the triviality of the character’s values.

After the Action. 2009

Oil on canvas, 83.5×64 cm. Photo: Gintarė Gritėnaitė

Žygimantas’ work is clearly infused with social criticism, and his means of expression is laughter, which, as Bergson asserts, shows a slight rebellion on the surface of social life. Sprawling through the museum’s halls, the exhibition generates thoughts about laughter as a museum value, demonstrating its timelessness. However, in the face of war, it is natural for laughter to weaken, overshadowed by the ominous wailing of sirens. We can only hope that the time will come when we can persistently mock our vices, raise a slight rebellion on the surface of social life, and receive a response. For now, as the artist said in the exhibition guide, we must learn to live in this crumbled reality, even though another reality is also possible, at least in new works.

Photography: Gintarė Gritėnaitė