Eileen Myles (they/them) is an American poet, writer, novelist, artist, and one of the 1990 candidates for President of the United States. We met soon after their talk at the House of Histories in Vilnius, in the exhibition ‘Goddesses and Warriors: 100 Years for Marija Gimbutas’ in 2022. We sat down in the historic Neringa restaurant at lunch time. Knives and forks were clanging around us, evocative of a historical battlefield. Eileen spoke slowly yet unstoppably, in a magnetic way, with short breaks for sips of Coke Zero. When I stepped back out into the street, I felt as if I had been transported to a different winter’s day.

For more than a year now, war has been raging nearby, and poets like Eileen are of the essence. This interview is dedicated to all those wishing to transport themselves to a different day and source some words and determination in it.

Monika Kalinauskaitė: There are four essential words which I associate with your work: language, time, poverty and cruelty. The audience I know you have here is comprised of people that often feel orphaned by their language, myself included. Your work presented me with a mode of engaging with words in a very direct, non-manipulative way; whereas my native tongue is currently very institutionalised. How do you sense the influence of language in different environments? Do you think there is a different writing process in Vilnius and New York, or any other environment with different linguistics?

Eileen Myles: Oh, yes. And I think it is also tied to the concentration, because the city of New York is very dense. There is a lot of language, there is a lot of human experience. There is the built environment, and a very interesting, special public space of the natural environment. But when I am in Texas, in a more expansive setting, I sometimes wind up feeling like the things I am thinking about come into the poems more often than the things that are affecting me directly. My surroundings have more effect in New York. I have always felt like being with language is taking soundings of the location: the signals bounce off of what’s there in a very palpable way. There is a joke in New York: if you go to California, it ruins your poetry. And I understood it when I first went to live on the West Coast. I was shocked: what do I do in a place where there more plants than people? How do I compress myself, which I think of as a big wavy thing, into a bone, like, say, in the poetry of Rae Armantrout? It’s a brilliant bone, it’s a smart bone. And the media: in California there is always a lot of information coming through. And this is in the aughts and by now everything feels this way. I started to think of it as little cars on a freeway, the constant traffic of tiny bytes of information. And it was that very Californian way which led me to understand, to feel how my work is always very affected by where I am. When I was finishing Chelsea Girls, I spent a summer in a very rural part of Pennsylvania on a large estate. And at first I was in shock, unsure what I was going to do with nature. And then I realised you just copy it and move around it like you do with the city: you let it influence the influence itself. But the softness of it was shocking, and I felt like my work changed.

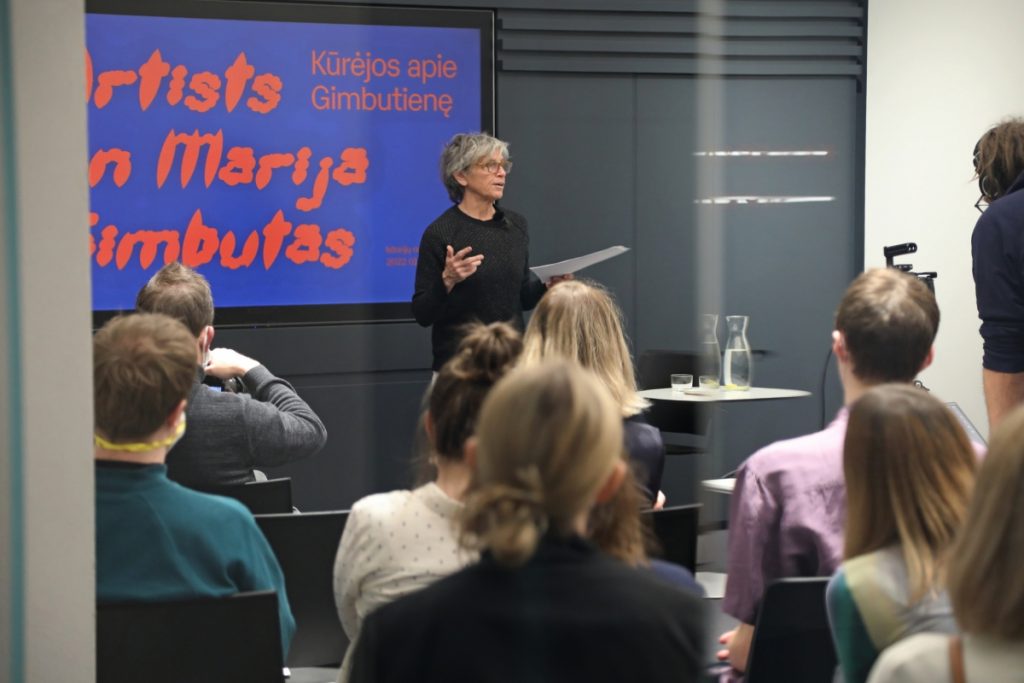

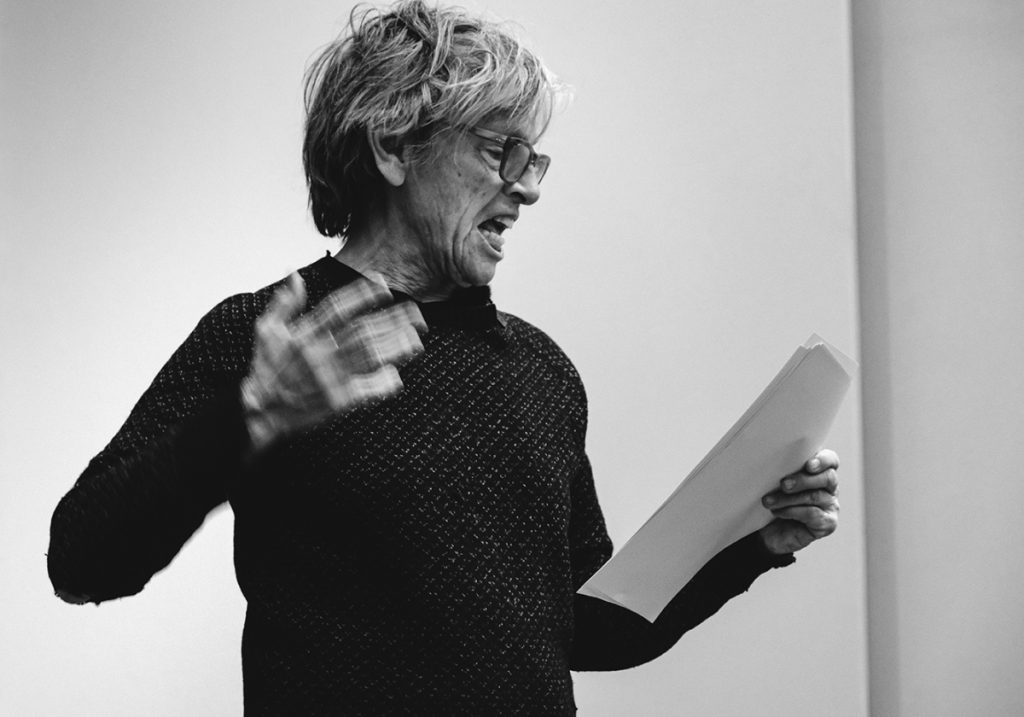

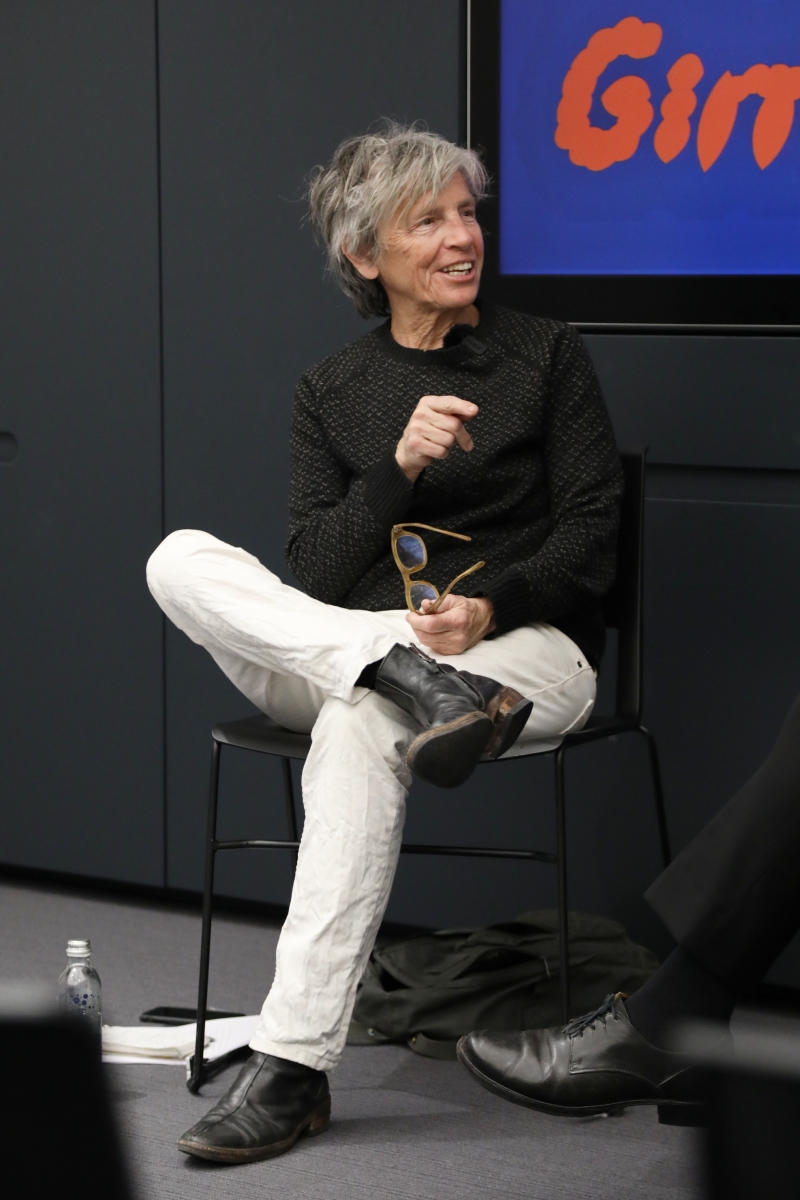

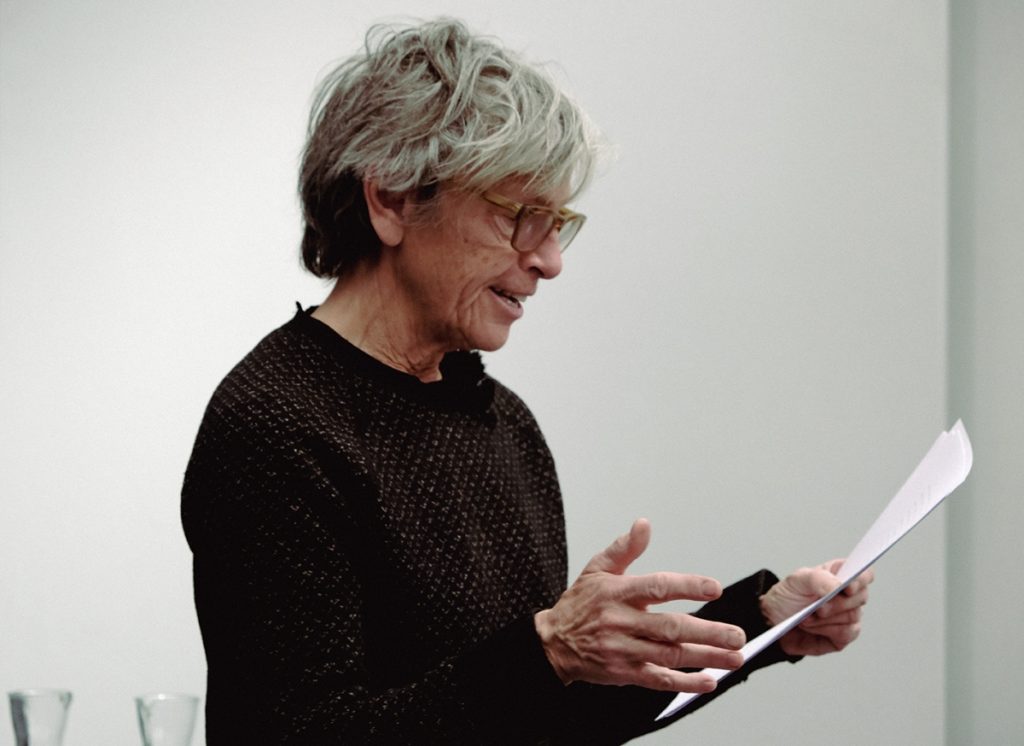

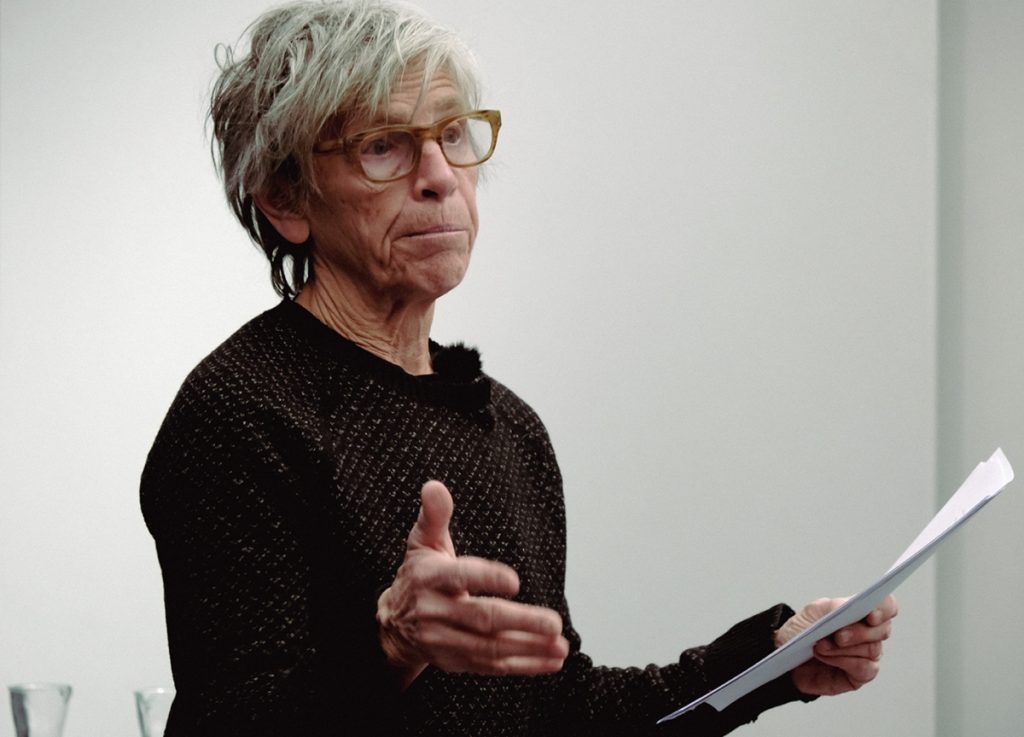

Performative conversation with Eileen Myles, House of Histories, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Tomas Ivanauskas

Performative conversation with Eileen Myles, House of Histories, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Tomas Ivanauskas

MK: And what about time? How does time affect being with words, with poetry?

EM: I think in the city I sometimes write out of a sense that there is not enough time. And when I have that thought, I react to it. How could it be that I have created a life where I do not have time to write when that is why I am here? When Robert Grenier wrote down I HATE SPEECH it was directed towards poetry that he believed should be more theoretical, and it shouldn’t be conversational, and it shouldn’t employ this American language that has been used since the Sixties. It is a great essay: it is hyperbole. And hyperbole is like throwing down the gauntlet: you make this outrageous claim or demand, and just by doing that you create space. So, whenever I had a sense in New York that I have a lack of time, I would get angry at that. I feel like I demand time. For a long while it was very hard for me to find time to work on my novel, because the time prose demands is spacious, but time in poetry is very fragmented. You can write between spaces, and prose is not the same way. You really have to create your own bubble for prose, and it is recursive: you have to read and keep reading. The pandemic felt like that, too: suddenly I couldn’t work on the novel, because there was no relief. Normally I would write and then go see people, I would separate myself from the process and go into another zone. And in the early part of the pandemic there was no other zone. I defaulted to poetry, which is amazing, because, somehow, poetry always works. I needed artificial constraints in the same way that I need people and obstructions continually to my own consciousness, which, I realised, just goes dead on its own. I did not realise I was requiring stimulation, and I was not requiring stimulation to write: I was requiring stimulation to not write. And if I had no way to not write, then I could not write either. I think that is a great challenge. I always look at artists who have been doing their work for years, asking, how do you keep going? For me, some of it is economic: I was not an academic, I was not supported by an institution at any point, and didn’t come to New York with family money. I did not know anybody. I was making it up as I went along. And that meant that I was willing to do different things, my sense of becoming a writer was sort of progressive. When I stopped drinking I was in my thirties, and I had many ideas about what I wanted to do as a writer, but my skills at the late end of my drinking felt reduced. I was only writing poems and I could not do anything else. And when I stopped drinking, I started doing performance. I started to write about art, which is important: when I was growing up, I was more focused on making art, drawing and painting. And it was assumed that I would go to art school, and it was seen as a part of my female lack of intelligence, in contrast to my brother being ‘the smart one’. I didn’t take that art path and I had a certain visual art hangover, a little bit of pain for the road not taken. I looked at visual art and I liked it, but I was conflicted. And when I got sober, I would stand in the gallery feeling just so excited. I felt immersed in the work and my only response was to write. I had more energy, I had more and more ways of gaining my own permission to stop and start more. Art writing taught me how to write prose, which I could not do before. I read poetry and it worked for me partially because I had never really figured out sentences. And working with editors who interfered with my process, I realised how malleable text was. That is in fact the big pleasure with prose, which is, in a way, like a giant poem. But it is also a little bit like film editing. And like quilting, and like all these different things that are pastiche. But it demands a different sense of time. I feel like the struggle for me as a writer of prose early on was the question, Who returns? Because I was not the same person who wrote what I wrote yesterday. So, I thought, how can the work be continuous and grow? Various writers, like Robert Walser, talked about writing a novel on the corner of a napkin. It made me understand that the sense of scale was so mobile that I did not have to come back entirely ever. A piece of me could come back, or some other character would come back, and then that character would write a piece, and the piece would accumulate. So, I started to understand time differently. Now it is more of a cumulative process, which is not focused on me, it is about space and shapes.

MK: I think a lot of the creative and the writing process is about breaking up with linear notions, and linear time is one of these very difficult notions. But there is also the idea of a singular method, a writing process that I don’t think really exists: sitting down and just doing it, so that after a month there is a novel which, of course, goes straight to the publishing house. Whereas I discovered most of the poetry I know from YouTube, because this way I can consume poetry while cleaning my house and while doing things in order to be able to also make things. I wonder if it is a wider mythology that really pervades the thinking of writers, of people who work with language? Is it not a little traumatising?

EM: Capitalism loves the myth of linearity. Even though everybody knows it is not true, you are continually invited to honor the myth. And it is so funny. One of my favourite sayings about this is by Chris Kraus: that since capitalism is insincere, it wants its fictions to be sincere. Like when Oprah loves a book, but then she feels betrayed as a reader, asking, Is it true? If it is not true, then she somehow has been betrayed as a reader, because writing has to fulfill a promise and make a contract with the reader and be sincere. When did this contract ever get signed?

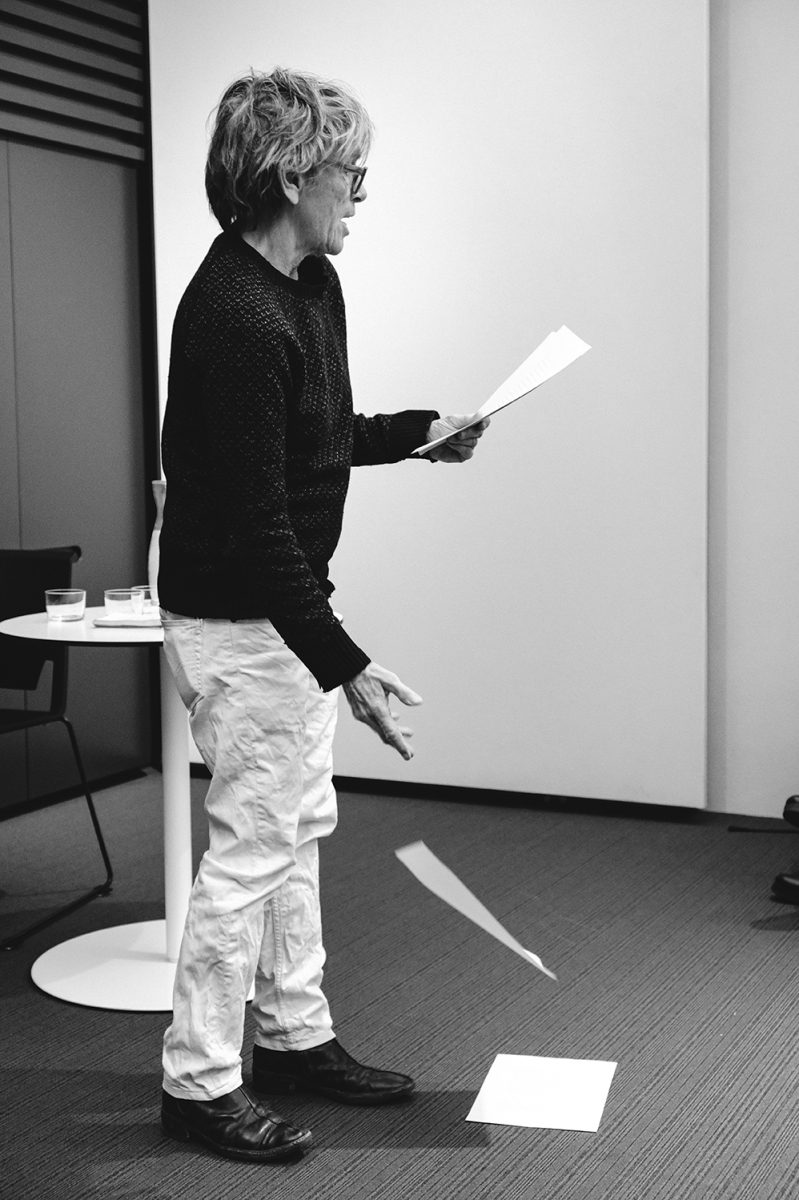

Performative conversation with Eileen Myles, House of Histories, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Arūnas Baltėnas

MK: I have a very fragmented relationship with contemporary novels. I often feel like they are written from a perspective that will never be accessible to me or anyone I know, and wonder if it is a product of this all-encompassing ideology, or something more specific, like being from a small country and having the notion of being a second-rate European. It is interesting that you bring up how capitalism specifically affects fiction. And how that fiction then affects life.

EM: Yes, I love the idea. You are talking about coming from a second-rate European country, and I feel like I have always been ‘second-rate’. I think it is very stimulating. It seems like a joke: people laugh about how women can have opportunities to do things differently because they are not mainstream. But it is true that when so little is expected of you, you can do lavish, wonderful, arcane things, because nobody is watching and nobody is expecting much. The first time I ever wrote something that I considered to be a novel, I had to keep it a secret. I did not want anybody to say I could not write a novel or ask how it was going. It seemed like the novel was a capitalist object, and still I was not entirely without capitalist dreams. When Chelsea Girls got published or when my next novel was going out to publishers, I had expectations that, surely, this was going to make a huge wave, and everything was going to be different afterwards. And everything was different, but not in the way I imagined. When I was first showing Chelsea Girls to editors, they said these stories do not finish. They never come to anything, they seem to disintegrate at the end. They wanted a narrative arc, this redemptive thing that must happen. And with all the weirdness that takes place on this planet, doesn’t the redemptive narrative arc seem like such a mythical thing? But they STILL want it!

MK: Yes, like applying a rationale to the natural, continuous unraveling of things, in which you might sometimes come out OK. I think writing makes you powerful in a way that you do not expect and never predict.

EM: Exactly, because it creates a space that you did not imagine. And now you are in the space, you are imagining what you are still making. And then it goes out into the world which has its own chemistry. And your work becomes something else, and then people come back and bring you pieces of it and say that it is very strange. I made a book of essays, The Importance of Being Iceland, which was mainly writing about art, but in lots of different bits and pieces. When I was putting it together, it felt funny: I thought that this inventory of things would probably not make any sense to anybody but me. And then when it came out so many people responded to it, and it turns out that all these strange keyholes opened into some very familiar hallways, while I thought I was making something very strange. That is something that always confounds me about the nature of this work. We’re making it, but we don’t know what it is or whose it is.

MK: Is there a way that this process can somehow be our capital? In the increasingly bizarre political and economic landscape we inhabit, one of the things I relate to most in your work is asking: How are your teeth? How many of us are confronting the reality of how we actually live? Is there something tangible to be done with all these words, which would also make it all a little easier?

EM: Totally! That’s it. I think we all know, somewhere, that writing is a currency, like our own Bitcoin. Since I was young, I had no money. The fact that I was a poet meant that people would buy me drinks, people would invite me to dinner, people would see me as an agent of hope or their opportunity to regenerate through poetry. People would want to have sex with me. And then it started to be a way of travelling, and it was just so strange. It seems like what you get for the work you make never felt and still does not feel literal. Except just by putting it into the world and the right or wrong people come in, and altogether you are creating a great system. A swarm. It may be just sentimental, but I do feel like if you believe the ridiculous thing, that writing will support you, then it will. The more passion and invention you put into it, the more you are creating something monumental that people will see, and that you are in, and then it will create more. When you put work out you become sticky. And all sorts of odd things, experiences and opportunities come to you because you are changing the shape of reality. It reminds me of what we know about particles, that they can be in more than one place at once. I think we all experience things at that level when we make realities and language. When I was younger, I had a lot of shitty jobs, doing everything from stuffing envelopes to being a messenger to being an assistant for a wonderful poet. I just had so many odd ways of making a living, but slowly it all became writing-related, and then, sometimes, it was only related to my own writing. But all of that was a kind of idealism. I read Kierkegaard when I was quite young, and one concept really stuck with me, that the purity of the heart is the will to desire one thing. And I took it literally. I was repeating a refrain: I just want to be a poet. And if I could just repeat enough, it would take me there. I think there is a way in which you create your own reality. And groups can do that, too. I think that is why poets form schools and gangs, because the collective has an influence and the collective takes space, the collective creates organs of publication and organs for perception.

Performative conversation with Eileen Myles, House of Histories, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Tomas Ivanauskas

Performative conversation with Eileen Myles, House of Histories, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Tomas Ivanauskas

MK: When I have to talk about writing I often articulate it as something that works to confront and to defend yourself against the inherent cruelty of your environment, whatever it is. At a particular moment we might talk about rape, we might talk about murder, we might talk about physical or psychological violence, but I find it very liberating and cathartic to just put it under this broad notion of cruelty and see how much we have to work with. What do you think of this position: a writer, a poet, in a cruel world, amongst many personal and political cruelties that we have to navigate with words if we want them to mean anything?

EM: I am drawn to some version of cruelty because I think when you acknowledge it, it becomes funny. It seems like when you inhabit something and then reanimate it, it becomes really ludicrous. Like reading a piece of my novel to the audience here, in some ways it was much lighter than I expected. It has many graphic descriptions of what sex felt like, or thoughts around it, which I realised were literal but also ludicrous, and that people would laugh at that ludicrousness. It felt like their laughter meant that we were inhabiting their bodies, not my body. I am shy about institutions. My last book For Now was the talk I gave at Yale, and I was wondering then: why am I so intimidated by Yale? I am not someone who went there, who taught there, who would feel … I had not ever been cleansed or approved of by the institution. I think I even felt some of that while reading to the audience in the museum: I was invited here and now I am going to come in and just talk about rape. It is funny that by the time that the act was completed it made more sense than it did to me in the first place, because it was very intuitive. I did not want to be attacking the hosts, I was probably concerned about my friend and their job and the institution and the embassies and other people who essentially brought me here. There was going to be something, the word doesn’t exist, improper or disorderly about it. But I think I learned something from my own work, for sure. When you’re writing a book about anything, you might wonder, how much did any of that really affect me? And the answer is, probably enormously. It is something that I have never talked about and no matter how much I talked about, I was still not talking about it. You live your life in the shadows of certain experiences or things that you know about the world. Once you step out from under you start to understand how that in fact is precisely how you know the world. I have become a person whose job is to do this, and it is strange, because I feel like in many contexts I continue to do this. If I am in a large public room in a culture that is mine and something is unsaid, I always feel like I am the person who has to say it. Partially because I feel silenced by groups, and I felt silenced in my education. I had to learn how to speak, and I think one of the things I learned from alcohol is that it let me take the opportunity to speak. And when I stopped drinking I had to learn to speak again. And one of the things I learned and keep learning all the time is that when you’re in a collective situation, where people are speaking and you want to enter the room, you are always thinking about something while trying to figure out how to become present there. And no matter how disconnected it seems from what’s going on, what you are quietly thinking is often the thing to say. I continually learn how organically my mind is connected to the place I am. I think I am always aware of my aloneness and my separateness, and yet I am not alone, and I am not separate. And I think by the end of my life, if I had become successful in actually saying what I was thinking I would have really satisfied myself in terms of what I was meant to be doing here. The feeling of disconnectedness: that is the pain, that is the violence. The one that I always feel. And it is militarised by actual violence. By the terms of a violent culture. There is a threat, all the time, that if you open your mouth there will be cruelty, there will be violence, there will be assault, there will be … There is danger.

MK: Maybe it ties to what you have said before: if an order of words can get you thrown out of Heaven, maybe there is an order of words which can also grant you protection.

EM: Yes! We want to find those words. And I think that the order of words that will grant you protection is an order that has to continually mutate and change. You have to change the locks almost all the time to be safe. And I think safe just means contemporary, in its most radical sense.