On Tuesday, 19 September, I boarded a coach to Riga for the first time. Waiting for me was uncertain weather—the kind rendering every clothing choice not quite right, where the real choice is which kind of discomfort you prefer to bear. The following day, in between forceful winds and the heavy-lidded blinking eye of the sun, I found myself at the base of the towering outline of a mountain also known as the National Library of Latvia, for the press conference of the 2023 RIXC Art Science Festival. At the time, I didn’t realise just how much pathetic fallacy and foreshadowing I had witnessed.

A brief google over my continental breakfast earlier that day informed me that RIXC was ‘a centre for new media culture, an art gallery and artist collective, that initiates projects at the intersection of art, science and emerging technologies’. The PDF programme in my e-mail added that the exhibition would open that same evening, followed by two days of keynote lectures from prominent figures in new media art (including some of the exhibited artists), the SensUS Augmented Reality exhibition tour in Esplanade Park, ‘artathon’ workshops and an evening of sound performances. My tourist ambitions were quashed.

Instead, I readied my body to absorb the dense research around ‘Crypto, Art and Climate’—this year’s theme—that promised to elaborate on three questions: How does crypto art relate to climate change? Can artificial intelligence offer solutions to environmental problems that human intelligence has so far failed to do? Will the persistent ignorance of our natural environment compel us to transition to a metaverse?

Hot and trendy topics!

Exhibition of RIXC Art Science Festival at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Over half of the artworks at the exhibition came from the European Media Art Platform (EMAP), with whom RIXC has a longstanding collaboration, and nearly all of the exhibited artworks used Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in their creation. Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits, the curators of the exhibition and founders of RIXC, explained that since their own space isn’t suitable for an exhibition of this scale, RIXC has partnered once again with the National Library of Latvia, occupying an exhibition space at the back of the ground floor comprised of a main space with a few nooks and two separate rooms at the back to the left and right.

With RIXC positioning itself between art and science, the location checks out, not least for the less conspicuous ties such as the use of blockchain technologies in archival practices. This duality is also felt in the exhibition itself, with some works appearing more at home as part of a museum’s interactive science exhibit. Everything feels compact, and as a result, slightly minute. At the opening, it was difficult to navigate around the tight corners and I can’t help feeling the works would’ve benefited from more negative space and breathing room.

Let’s take Anna Ridler’s Myriad (Tulips) as an example—a mosaic (one of three) of over a thousand polaroids of tulips she photographed and categorised herself with handwritten annotations below each photo. From her keynote, she elaborated on her interest in issues around creating data sets, the process of discrimination, ownership and fairness, relating it to the historic echoes of taxonomy and the human tendency to classify the world. Breathtakingly overwhelming, the work pulls the curtain behind the immense and usually invisible undertaking of training AI models to recognise information in images.

The amorphous sucking up of everything…

The mosaic invites viewers to zoom in and out, yet take one step back too many, and you’ll find yourself inside Paula Nishijima’s installation Plug-in Habitat. Nishijima’s work centres around her research on the adaptive quality of plants, resulting in a sprawling wall diagram, making-of documentary film and an illustrative installation comprised of a dome, cushion plants, screens and modules (speculative biological structures made from biodegradable plastic).

Both of these works highlight the process behind an outcome. While Ridler’s mosaic uses the process as inspiration, Nishijima’s overexplains it, destroying the artwork’s intrigue to an extent. However, I think it is exemplary in highlighting the position art can take in relation to science, answering the question of what role artists could fulfil in a continued future of climate disasters where pragmatism rules above all (think about the scene in ‘Interstellar’ when the school headteacher says ‘right now the world doesn’t need more engineers, it needs farmers’).

‘Myriad (Tulips)’ by Anna Ridler at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘Plug-in Habitat’ by Paula Nishijima at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Around the corner to the right, Carolin Liebl and Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler’s installation and film, Fading Substance, suspend a fleshy bit of biodegradable plastic in a carefully insulated caustic bath that will degrade it over the course of the exhibition. On the wall, a series of photos and a video show the process on a microscopic scale, with muscular tendons snapping into nothingness as matter breaks down into CO2 and water. It centres a broader idea of technology in the innovative development of ‘sustainable’ plastic, acting almost as an advert for it.

Next to this, two vertical screens play Jurģis Peters’ film, Memories of The Distant Future, where images from his personal archive are continuously reimagined by AI into abstract, melting, Venetian architectures, reminiscent of something but… not quite. Questioning how our memory and cognition might adapt to the proliferation of AI-generated images, it exploits the uncanny valley for a viewing experience that is mesmerising, unsettling and surreal.

We have agency in what and how we use technology, or how we embed it in our daily life. But once we use it, it’s a delayed and slow feedback loop that becomes difficult to interfere with as we’re usually unaware of it.

‘Fading Substance’ by Carolin Liebl and Nikolas Schmid-Pfähler at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘Memories of The Distant Future’ by Jurģis Peters at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

In the same area, there are two VR works. Līga Vēliņa’s Shifted Realities is a pseudo museum tour of a dark, three-storey floating island of ruined classical architecture, containing halls on real and speculative human evolution, starting with recounting how we got to where we are now, with the following two floors each offering either a utopic or dystopic vision of a future where humans have fused with AI. Beyond the aesthetic approach privileging a euro-centric idea of human history, the utopic and dystopic scenarios feel recycled, featuring either Cyberpunk-tinged concerns or transhumanist wishful thinking. Dividing these futures into such polarities flattens nuance that would’ve otherwise made these proposals more thought-provoking.

Neither humans nor robots have clear borders. It’s an abstraction to have an argument. Both of them are embedded in wider systems.

Ieva Vīksne’s Unravel is far barer, giving its participant the ability to experience what it’s like to be an algorithm being trained, with the participant having to do tasks like physically sorting textures, colours and objects into different categories. While a novel experience, it’s by design incredibly mundane and due to its minimal aesthetic dimension, doesn’t invite a participant to stay for long.

VR was also one of the main topics of Chris Salter’s keynote lecture, who remarked on the sense of unfulfilled potential that has been attached to this technology since its inception. That sense carries on here, although Vīksne’s interactivity in relation to its subject matter does go further in transporting the viewer into a typically inaccessible digital perspective.

Participants with Līga Vēliņa’s ‘Shifted Realities’ and Ieva Vīksne’s ‘Unravel’ at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Perhaps meant to be the exhibition’s crown jewel, to the left of the main space, Memo Akten’s Distributed Consciousness conjures a mosaic of AI-generated ‘tentacular critters’ that alternate between their cartoonishly colourful octopus forms to geometries of light, speaking unto the viewer a manifesto, co-written between humans and machines, that speculates about the nature and future of consciousness, imploring the viewer to do the same.

Do you have a mind or does your mind control you?

Unlike most other video works in the exhibition that use headphones, the manifesto seeps out of the speakers in viscous drops of eerie synths while a robotic voice stalks the corners of the tight space. While only experiencing the artwork, I found the text simultaneously dense and vague; it was hard to find something concrete to take away with me, even though it was clear Akten had plenty to share.

Akten’s keynote elaborated further on his philosophy concerning AI and human creativity, focusing on common questions of authorship that arise from using this technology and the long-term cognitive impact of externalising imagination in this way.

This is a Faustian bargain. There is evidence of our attention spans getting shorter and our memories becoming more fragmented. Neurological changes are happening within us. I am, in effect, collaborating with every single person in the creation and output of this tool. I’m collaborating with millions of people. The results are the fruits of our collective, distributed consciousness.

Sidestepping the question of remuneration and copyright, I found what he said about people’s inability to accept the death of human exceptionalism fascinating. Are we clinging on to the virtuosity of the individual, of the human intellect? I’m not sure I fully agree. Artists don’t create in a vacuum and through the process of making, engage in a dialogue with all their inspirations. I think it’s more correct to see this as another iteration of collective creativity; one that is driven by the need to quantify, standardise and rationalise the world, to make all that is invisible tangible and demystified.

To the side of Akten’s large screen and its speakers, a beanbag waits in front of a TV for someone to pick up the headphones resting on it. This is where Rosa Menkman’s Refraction in Light and Time plays on a loop; a glitching, digital film about the Angel of History exploring a cave to find a cyclops and learn about its future vision. While carefully combining speculative science, technology and mythology in a focused act of worldbuilding, the work cannot fully establish its own atmosphere, drowning in the sound bleed of its neighbouring artwork.

Past Menkman’s film, in the left back room, we find Zane Zelmene’s Synthetic visions. It features a pillar with a ‘hologram’ on one side, emerging from a circular base of symbols, wires and screens showing AI-generated footage while speakers play a monologue powered by ChatGPT. The text speculates about the potential of AI to unravel the mysteries of existence while advocating for universal access to AI, peaceful coexistence with humans and presenting a roadmap for regulation. The videos feel very reminiscent of those YouTube ads trying to sell questionable books about ancient civilisations and aliens (or maybe that’s just my algorithm… have I just exposed myself?).

‘Distributed Consciousness’ by Memo Akten at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘Refraction in Light and Time’ by Rosa Menkman at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘Synthetic visions’ by Zane Zelmene at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

While making my way through these explanations and elaborations of various technologies and their potential for ‘humanity’ (as a unified whole), I can’t shake this uneasy feeling that I’ve forgotten something… Wasn’t this festival supposed to answer some difficult questions about the relation of these technologies to climate change?

I suppose there’s no more ignoring the elephant in the room of the festival’s programme—the complete lack of direct capitalist critique.

Are we really talking about climate change or are we lost in some kind of darkness?

Can we seriously address the seriousness of the climate crisis without revaluating humans’ relationship to consumption and the seemingly fundamental self-conception of humans as endlessly-unsatiated-progress-seeking explorers? An idea like de-growth feels far more radical, meaningful and actionable for those seeking answers. What role could these technologies take on in a world that shrinks and finds balance, rather than one that expands, bloats and grows diseased? While offering many utopic and dystopic visions of our future with these technologies, the festival never dared to ask whether we should even be heading down that road. It assumed our intertwinement with them was a foregone conclusion so instead, we should focus on the ways we can use them (sounds a bit… fatalistic).

Anybody want to react to this provocation?

Coming back to those three questions the festival set for itself, some answers could be found in the keynote lectures. Frustratingly, much of the discourse was ecomodernist. For example, Eric Nowak’s keynote focused on the value of natural resources and how cryptocurrencies could be used to compensate for deforestation in the Amazon by funding replanting initiatives.

I’m an economist so I believe climate change is an effect of market failure because we don’t prize the use of natural resources. For hundreds of years, we produced using nature without paying for it.

Ecomodernism essentially attempts to maintain the status quo of consumption and progress, just doing it ‘green’, with the goal of ‘decoupling’ growth from impact. Imagine unfathomably large walls of carbon capture machines or new-generation ultra-capacity lithium batteries. Ecomodernist solutions are hi-tech with a bubbling sense of optimism that the climate crisis is just another situation we can innovate our way out of on the path to interplanetary civilisation.

At the end of the day, I don’t care how and why we pay for it. We need to find a way to get money from here to there. Without the use of this mechanism, deforestation will continue to grow at a great pace. Offsetting may not be a perfect solution but at least it is a solution.

Moving away from this perspective means the questions become directly political and economic rather than generally existential. The politics of exploitation under capitalism cannot be disentangled from the planetary catastrophe of climate change as its main causes—industrialisation, over-consumption and lack of regard for the intrinsic value of nature—find their roots both in colonialism and our understanding of ourselves.

Does anyone really believe it’s better not to have this project than to have it?

It may seem that I’m flirting with an obvious contradiction: asking a festival based around new media art to shun its tech. However, there already exists an alternative vision of the future where through rethinking our relationship to nature and technology, humans avert the climate catastrophe and take on the role of caretakers to the environment—Solarpunk. In this future, technology coexists harmoniously with both nature and humanity, helping us to cooperate with the environment, rather than struggle to control it. This shift in thinking allows us to focus on technologies that are conducive to a fair, just and equitable world. Incisively political, Solarpunk is clear in its stance that capitalism and colonialism aren’t compatible with this future.

To be clear, I’m not saying the artists in this exhibition are somehow agents of capitalism. I just wish the framing of the festival and the ideas it chose to highlight hadn’t fallen into familiar ecomodernist tropes that don’t engage meaningfully or realistically with the political, economic and social complexities addressing this crisis calls for.

They are very optimistic about the future. What I imagine is way worse.

That is not to say the exhibition doesn’t make attempts at critiquing corporate interests. A few artists chose to examine the Goliath tech companies they’re fighting for the steering wheel of progress, bringing chunks of their gargantuan bodies into the space, like an ancient hero fulfilling a quest from the gods.

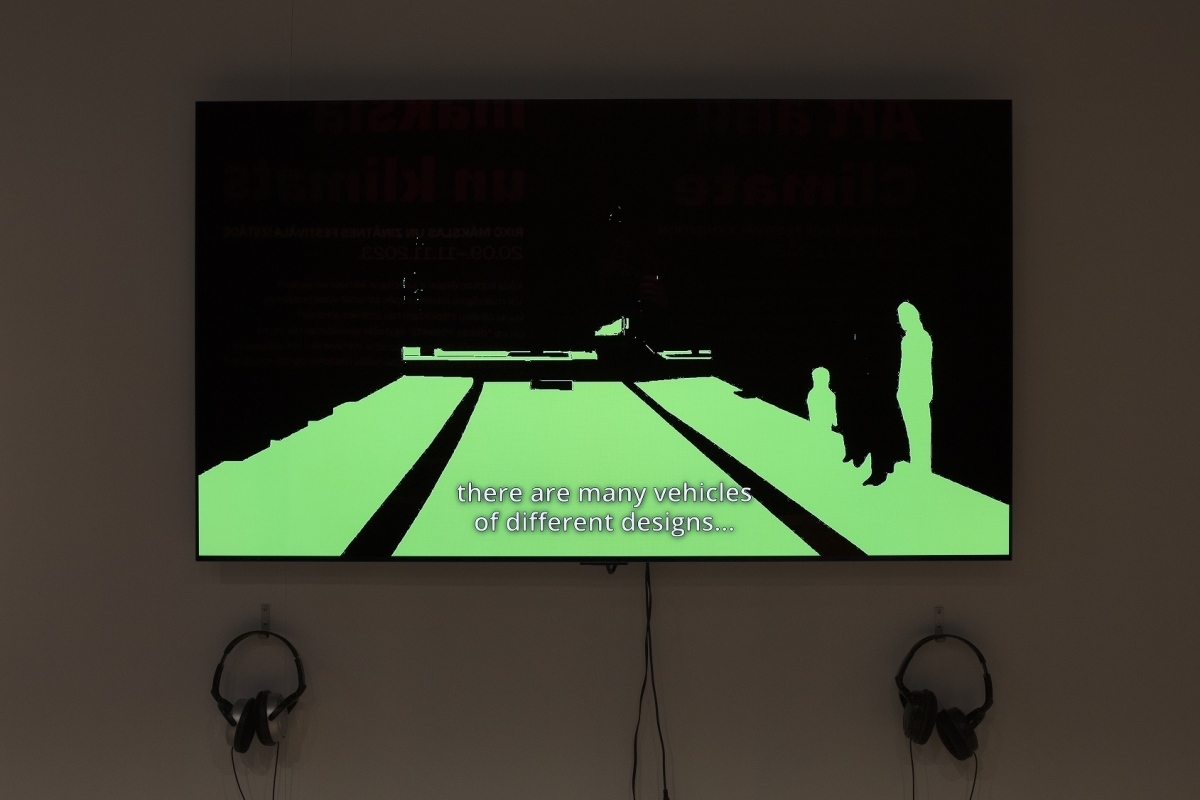

Greeting us at the entrance is Nicolas Gourault’s Unknown Label, a film of screen-recorded footage where faceless micro-workers from the ‘Global South’ recount their experiences of painstakingly marking and labelling objects in street images to train a self-driving car algorithm. Highlighting their exploitation and income inequality, the film forces us to face the neo-colonial tendencies of Fortress Europe, who would much rather pretend to be past doing ‘all that’. Gourault’s editing of the footage into a devolving world of disembodied objects lends an edge to what otherwise would’ve been a more straightforward documentary.

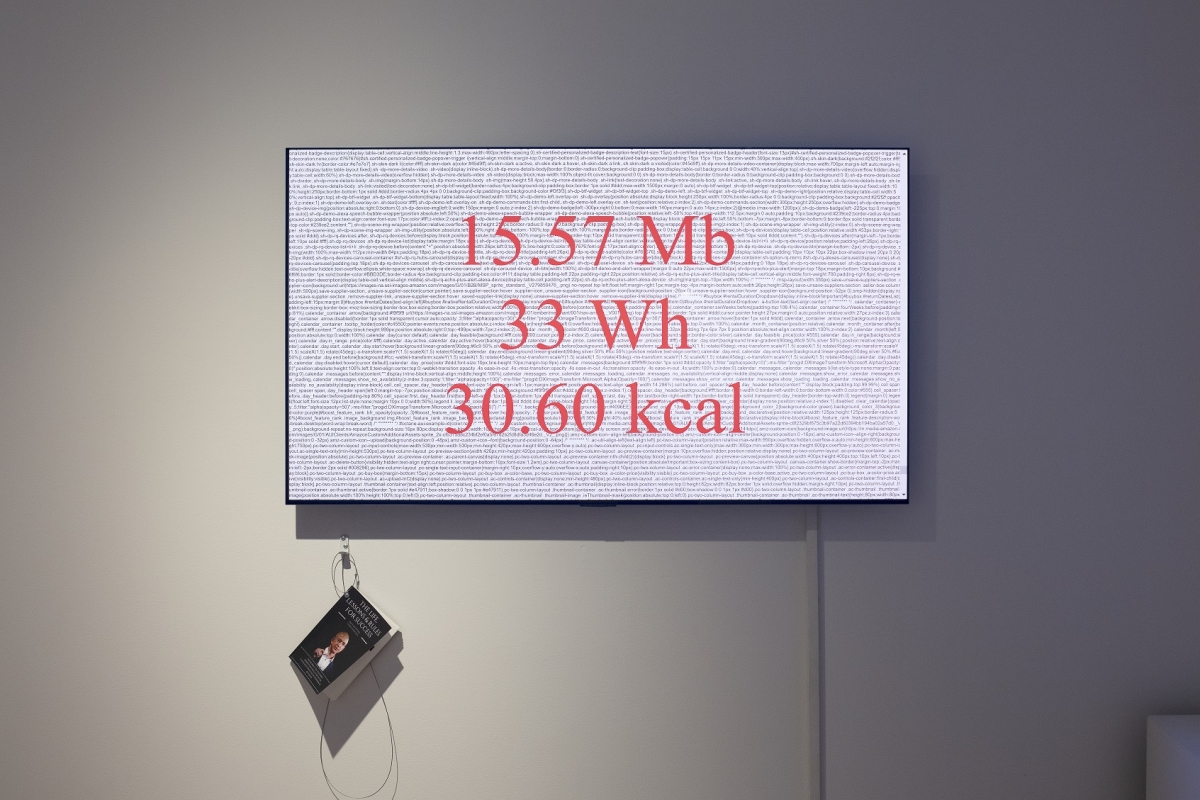

In the room to the left, Amazon Dance—The Picking Algorithm by Nico Angiuli and Katerina El Raheb, is a video performance in which performers physically enact Amazon’s algorithms using their bodies and objects such as rolls of tape and tangerines. Questioning the value relation between human and machine labour, the performance was filmed on a stage with a few cameras and a variety of cuts but minimal digital intervention, making it difficult to ignore the feeling you’re watching a video of a performance rather than a video performance. Honed on the same target, Joana Moll’s The Hidden Life of an Amazon User displays the energetic cost born by users when running searches on Amazon. Red numbers, against a background of an incoherent stream of code, gradually increase in megabytes, watt-hours and calories.

‘Unknown Label’ by Nicolas Gourault at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘Amazon Dance—The Picking Algorithm’ by Nico Angiuli and Katerina El Raheb at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

‘The Hidden Life of an Amazon User’ by Joana Moll at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

In both works addressing Amazon, it’s difficult to understand what the artists want us to do about these various forms of labour beyond acknowledging their existence, choosing to ‘shine a light’ rather than making a pointed political or economic statement. While watching Angiuli and El Raheb’s video, I was waiting the entire time for a worker to need to use the bathroom, yet this moment never came. There were no complications.

How do you know someone didn’t go to see the AR piece and then went home and planted clover in their backyard? We don’t know what the impacts of these works are. I think they play out in the individuals who see them.

Finally, Moll is joined by Emanuel Gollob’s disarming, an installation (or live performance?) of a robotic arm, severed from its factory, writhing on a padded floor of repurposed children’s mattresses, trying to stand up and take its first steps after retirement. Moll’s adjacent artwork takes on new meaning almost as a window into the mind of this creature. Gollob’s work, maybe unintentionally, proposes an answer for what the future life of these technologies, in a world that no longer can afford to use them, might look like. Watching it try and fail is both tragic and heart-warming.

‘disarming’ by Emanuel Gollob at the National Library of Latvia, 2023. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

At the opening, I asked Gollob if it could ever actually stand up or if it was limited by its programming. He explained that all knowledge has a frame but there was a minuscule possibility (so like monkeys, typewriters and Shakespeare?). I wonder if controlling the limits of someone else’s intelligence makes you more aware of how your own intelligence has been constructed and by whom…

Sometimes you hear the sound of resistance between the body and the environment, which made me think about what learning actually means. It’s a question of your surroundings; you try to find less resistance or go against the resistance. I found that interesting as an ongoing process, rather than a static point.

At the end of my time in Riga, on the coach back to Vilnius, I reflected on how informative the festival had been in countering mainstream narratives about AI and blockchain technologies, especially concerning art. Making the distinction between the unethical web scraping approaches of tech giants and artists spending countless hours creating data sets to train their own algorithms, it’s clear there is so much care and communality with the non-human involved. Against the backdrop of the explosion in AI-generated content on the web, I feel sad for artists who have already been exploring this field for a while having their work recontextualised on such a mass scale. It would’ve been interesting for that tension to be tackled head-on in the artworks, rather than ignored with the hope it would go away.

And when I considered if the festival managed to answer those grand questions about climate change it set for itself, I couldn’t help but feel they fell at the first hurdle.

Humans were always transforming, so in which state do you want to freeze?

Do you want to freeze?

I wouldn’t say so. I want to be aware of the change and have agency in it.