This spring, the Paris-based Lithuanian artist Ieva Kotryna Ski presented the exhibition ‘stonewashing’, her largest solo project to date in Lithuania, which will be on view at the Editorial project space in Vilnius until the end of June. The works on display not only continue the artist’s ongoing exploration of parallels between geological phenomena and queer identity, but also invite viewers to reconsider the relationship between surface and digital imagery, and the tensions that sometimes arise within it.

I meet with Ieva Kotryna just a couple of days before the exhibition opening, and it seems that with each passing minute, the artist, freshly arrived from Paris, is diving deeper into both Vilnius itself and the significance of her work in the Lithuanian context. Our conversation flows from her audience award-winning video piece Sinkhole at the JCDecaux Award 2021 to her experience marching in Kaunas Pride. But we focus on the latest chapter in her artistic practice. Over the course of an hour in a Vilnius courtyard, we trace the last few years of her work, spanning journeys to Northern Ireland in search of natural geological formations, and reflections on what it means to create in between: between Vilnius and Paris, between digital and mechanically captured images, between deep time and the everyday.

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: Although your work has been familiar to the Lithuanian contemporary art audience since the video piece Sinkhole was shown (and won the audience award!) at the ‘JCDecaux Award 2021’ exhibition, the new show ‘stonewashing’ at the Editorial project space is arguably your most ambitious project in your home country to date. What have the last four or five years of your creative life looked like, and how did they lead you to the point where ‘stonewashing’ is now taking shape?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: The period following Sinkhole wasn’t marked by a quick transition into another intense project. The first year after its release was dedicated to completing my Master’s studies, during which Sinkhole itself became a central focus, so the deep dive into its themes continued naturally. During that time, I wasn’t otherwise very creatively active; of course, I was exploring certain topics, some of which are reflected in the exhibition ‘stonewashing’. Later, another important project for me began, the ‘Preila Project’, which I’m currently developing together with Ignė Narbutaitė. After a preliminary presentation in Preila last year, which we titled ‘Thing-Finding’, we’ll be presenting the completed project this June at the Pamario Gallery.

The impulse for this collaboration came from Neringa Municipality’s residency grant call at the Nida Art Colony. Since the Curonian Spit is a place of deep personal significance to my family, and my cousin Ignė and I had long been discussing the idea of working on something together, this opportunity seemed ideal. The creative process lasted nearly three years. Its extended duration was mainly due to the geographical distance (Ignė lives in Vilnius, and I’m based in Paris), as well as the challenges of coordinating our schedules and finding a suitable space to present the work.

In parallel with these major projects, other creative activities and the development of personal ideas also took place. One such project was ‘Dyke Into’, realised in the streets of Vilnius together with Janina Sabaliauskaitė, using JCDecaux billboards. The project’s roots go back to the research I conducted for Sinkhole: while studying geology, I came across a phenomenon known as a ‘dyke’, where one type of rock intrudes vertically into an older formation. In English, the word also has another, more contemporary, meaning, referring to homosexual women. On getting the opportunity to use public billboard space, the idea came up to merge these distinct meanings of the word ‘dyke’.

My interest in geological formations continued to develop over time. During a residency in Northern Ireland (at CCA Derry Londonderry), I learned that the region’s coastline features numerous naturally formed dykes, so I began travelling along the coast to document them. As I went, my focus expanded beyond this specific geological phenomenon, to broader reflections on geological processes in general, and how they shape our perception of the landscape. These contexts became the foundation for the video work featured in the exhibition ‘stonewashing’.

Ieva Kotryna Ski, faults and folds, 2025. 09:12 min., HD video loop (video still)

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: As is noted in the accompanying text for your new exhibition, you’ve been exploring geological processes and their relationship with contemporary environments since your earliest works. I read that your interest in geology comes from your grandfather, a geologist whose research focused on sinkholes. Later, your practice evolved towards reflections on geology and linguistics, which led to the 2023 public billboard project ‘Dyke Into’, inserted into the urban context of Vilnius. What kind of relationship with the landscape, and what new nuances of it, does your new video work faults and folds reveal?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: Geology entered my artistic practice thanks to my grandfather and his research. However, my earliest works were more focused on exploring the aesthetics of phone-recorded imagery. The first fragments, capturing everyday moments in my life and the life of Vilnius, emerged rather accidentally, partly due to a visual ‘glitch’ in the phone camera itself. While studying film in Paris, I wrote my Bachelor’s thesis on the significance of phone-shot footage in documentary cinema. But during my Master’s studies, I changed direction and began grounding my work more deeply in geological themes.

At the same time, it was also a natural extension of my interest in certain technological aspects. While working on Sinkhole I began to explore the relationship between the surface of the digital image and the surface of the Earth, the ‘errors’ in digital imagery, and how different visual technologies shape our perception of reality and the landscape. These investigations are even more clearly articulated in my new work faults and folds.

I’m particularly interested in the aspects of the instability and the ongoing transformation of rocks, as well as a kind of geological ‘deception’. Something that appears solid and immutable can, in fact, be soft, fluid, and capable of completely changing form, visually misleading us. This theme of deception also plays out on a broader level of visual perception: how a visible texture may not correspond to the actual properties of a material. In the video piece, there are also moments when this visual manipulation is intentional, aimed at misleading the viewer and playing with their perception.

I want to emphasise that in faults and folds, the image is no longer purely digital. After many years, I picked up an analogue film camera again. However, the footage captured on film doesn’t serve as the final result; it is further processed using AI-generated animations and editing software effects. I think there’s often a temptation to show film-based footage (whether photographic or moving image) without much selection, simply because it tends to be inherently beautiful. At the same time, it’s true that images captured on film have a very different kind of vitality. Still, I’m drawn to digital imagery, precisely because there is no single digital image. There are countless variations in quality, depending on the devices used to capture them. Low-resolution images often feel to me like they convey reality more accurately, as we actually experience it, whereas ultra-high-definition visuals can sometimes appear like renders, making the recorded environment deceptively perfect. Our perception of image quality constantly shifts with each new technological development: what might have seemed like high definition around 2005 now appears significantly degraded.

Ieva Kotryna Ski, stonewashing, 2025. Exhibition view at Editorial, Vilnius

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: As I understand it, the process of creating this exhibition was marked by an unfortunate incident. While searching for geological dykes along the Irish coastline, your camera fell into the water, forcing you to work with a low-quality video camera and an analogue film camera. Are the digitally modified or AI-animated photographs seen in the exhibition a result of losing that original camera, or was it more of a deliberate attempt to explore new ways of working with the image, ways that, as you put it, strip it of the ‘stability’ we typically associate not only with photography but also with the rocks depicted? Could this be a way of exposing that supposed stability in a new light?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: Artificial intelligence (AI) entered my practice partly as a natural extension, and partly due to practical circumstances. After losing my main camera during the trip, I was forced to collect most of the visual material through photographs and low-resolution video footage, which didn’t fully align with my initial vision. While I had already used computer-generated effects and image modification tools before, AI initially attracted me as a new instrument I simply wanted to try out. I began experimenting without a clear project in mind, and quickly realised that achieving the desired results wasn’t easy; it requires a specific set of skills, not unlike the work of a ‘prompt writer’.

It was only while preparing for the exhibition that I realised AI could actually serve a purpose in this context. Although I’m naturally critical of the rapid adoption of ‘trendy’ technologies, and I myself found it somewhat ironic to give in to this wave, I came to understand that AI could help me solve a specific visual challenge. Since most of the material I had was static photographs, AI offered a way to introduce movement and transformation into them. I began experimenting, playing with images and the capabilities of AI, and the results integrated organically into the project’s overall concept. This interaction with technology allowed me to explore how landscapes are formed, the relationship between image surface and authenticity, and the moment of deception and uncertainty: when it becomes difficult to distinguish what in the image is actual nature and what is technological manipulation.

As with many of my projects, this work emerged largely through experimentation and the editing process. The question of how to visualise the transformation of landscapes or rock formations, changes that are not always visible to the naked eye, was not resolved in advance; it evolved through trial and error. Working with AI was marked by unpredictability: sometimes I would try to describe the desired result in precise terms, and at other times I would simply upload an image and let the algorithm decide what to do with it. This process, spending hours at the computer testing different variations, would eventually lead to visuals that naturally wove themselves into the overall narrative. While sometimes an idea comes first, and then seeks its visual form, in my practice it often happens the other way around: the image generated through experimentation offers the idea or the way forward.

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: You’ve been living in Paris for some time now, where you completed a Bachelor’s in film and a Master’s in artistic research, and where you continue to develop your practice, often collaborating with peers from the art field. Although it doesn’t seem like you’re observing Lithuania’s art and cultural scene from a distance, physical separation inevitably affects the sharpness and sensitivity of one’s perspective, especially on issues that may still be perceived quite differently in Paris and Vilnius. How do you feel personally about creating and living between cities? How do your experiences of Paris and Vilnius intersect and shape your work?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: The theme of the city as a source of creative inspiration is especially important to me, something I reflect on often. I remember how, after moving to Paris, where I’ve now lived for eight years, I felt for a long time that the city didn’t inspire me as deeply as Vilnius did. Vilnius always seemed to spark creativity; my first phone-recorded video works captured precisely the experiences and everyday life of the city. Paris, with its overwhelming cultural and everyday abundance, initially felt stifling: it was difficult to connect with it on a personal level, to find my own spaces and references.

Moreover, in recent years, the works I’ve created haven’t been directly related to the city I live in: my inspiration often came from travelling, frequently in natural settings. Still, recently, perhaps due to the many years I’ve spent in Paris, the deeper familiarity I’ve developed with it, or the more active reflection on my relationship with the city, I feel it is beginning to return to my work.

In the current exhibition, I sense a certain intertwining of different aesthetics and emotional tones that were perhaps more separated in my earlier work: for instance, there was a clear distinction between the pieces made before Sinkhole and those that came after. While I don’t speak directly about cities or depict them overtly, ‘stonewashing’ subtly pays homage to Vilnius. As an object for sitting, we chose an old concrete curb found in a landfill, exactly the type of curb that’s now being replaced en masse throughout the city. And yet, so many memorable hours were spent sitting on those curbs in Vilnius.

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: Do your works carry a greater political or social weight when shown in Vilnius, and does that affect how you perceive the significance of your own artistic practice?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: The project ‘Dyke Into’ stood out with its clear social and political weight. I created it specifically with the Lithuanian context in mind, aiming to increase visibility for queer people, and to introduce the wider public to the meaning of the word ‘dyke’. I thought that in Vilnius, unlike in Paris, where the term is quite popular, and is often associated with culture and fashion, and rarely provokes intolerance, it was still less commonly used outside the queer community, let alone widely understood. Historically a slur, the word ‘dyke’ has been reclaimed by the community, and transformed into a symbol of female strength. Initially, I considered presenting ‘Dyke Into’ in public ad spaces in Kaunas: after experiencing extremely hostile reactions during Kaunas Pride, I felt that speaking on these issues was even more urgent there. However, JCDecaux couldn’t offer any available billboard space in Kaunas, so we ended up showing the project in Vilnius. While I anticipated a stronger public backlash, the actual response revealed something different: a general lack of understanding of the term. The most telling feedback came in the form of a complaint submitted to JCDecaux, stating that an ‘offensive word’ was being used in public, highlighting potential differences in perception even within the LGBTQ+ community, or between different generations. That incident pushed me to further explore the context of the word’s use, and the politics of who has the right to use it.

The multilayered play with language also extends to the title of the newest video work faults and folds, which combines two geological terms: ‘folds’ referring to the bending of layers of rock that leads to mountain formation, and ‘faults’ meaning fractures in the Earth’s crust, often where geological dykes are found. But the English word ‘faults’ also means ‘errors’ or ‘mistakes’. This dual meaning links geological processes to the theme of visual perception, its fragility and potential for distortion. This deliberate, and at times untranslatable, layering of language opens up deeper reflection not only on the transformations of nature and landscape, but also on the nature of the image and the ways it is interpreted.

Ieva Kotryna Ski, stonewashing, 2025. Exhibition view at Editorial, Vilnius

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: It’s worth noting that you have a remarkable ability to speak about queer identity in a highly nuanced and multilayered way, embedding the theme within the contexts of geology and the notion of geological or deep time, something fundamentally inaccessible to our human, earthbound existence. How and when did narratives related to queerness begin to take shape in your practice? And with each major work, do you find yourself exploring different facets of this theme, perhaps ones that feel personally relevant to you at that moment?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: My identity naturally weaves itself into my artistic practice: it’s an inseparable part of my life that, like any other personal experience (such as love), inevitably surfaces in my work, even if the work isn’t solely about that. The project ‘Dyke Into’ was a direct expression of this connection: a conscious effort to increase the visibility of queer people in Lithuania, while also exploring the meaning of the word ‘dyke’, a term reclaimed by the community and transformed from a historical slur into a symbol of strength. It’s important for me to speak about this, because it’s painful to witness how basic aspects of identity can still shock or cause issues. In my most recent work, this thread continues, but alongside it emerges the theme of desire. Here, desire is explored through materiality, whether it’s the texture of fabrics like denim, or the substance of rocks themselves. Within the community, the word ‘dyke’ also carries associations with desire, gaining a broader resonance. This theme connects to ideas I’ve touched on in earlier works (such as Sinkhole), where I explored the relationship between the tangible and the intangible, encounters with matter of unimaginable scale, or with inner feelings that can manifest as overwhelming, even frustrating desires.

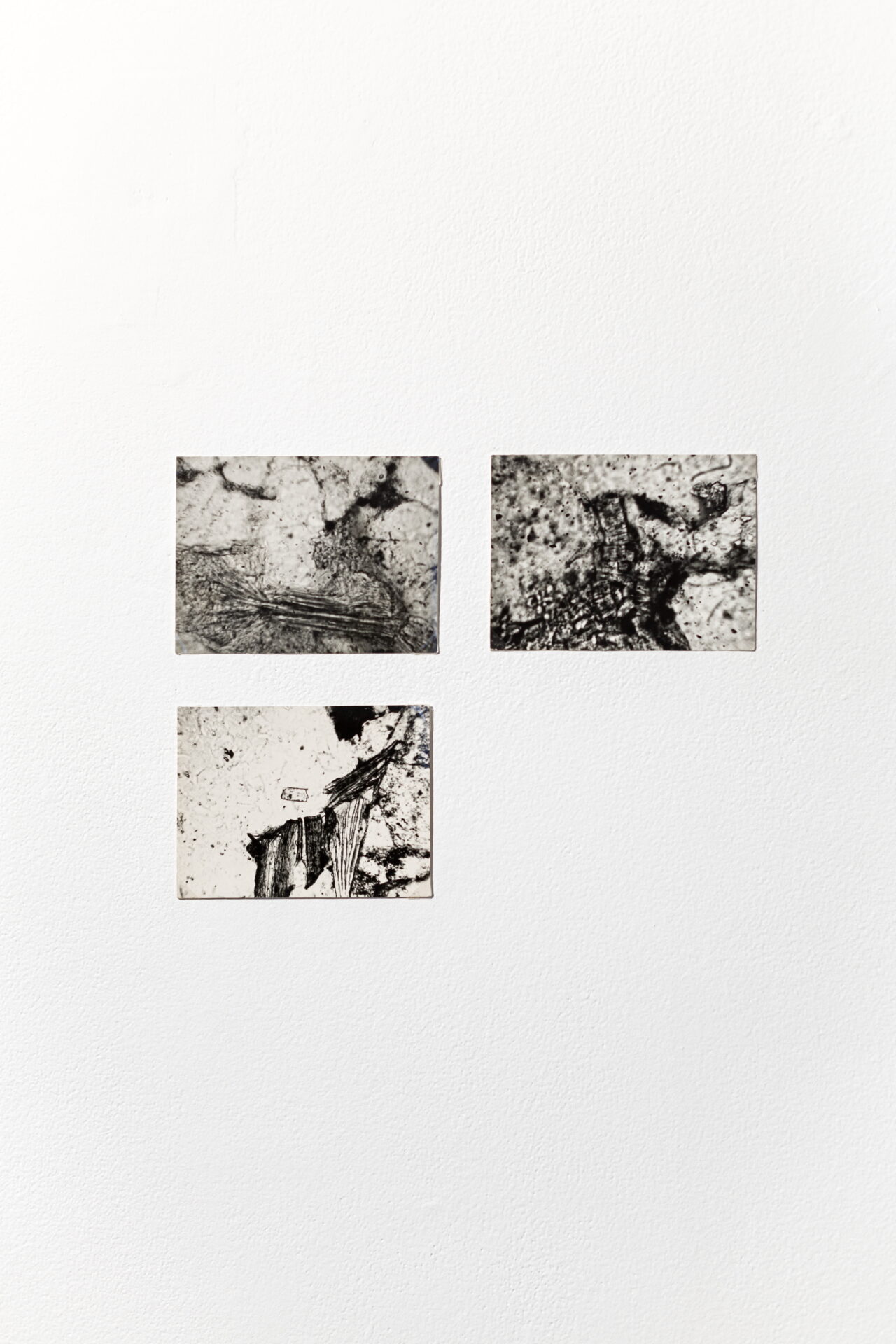

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: Alongside the video work faults and folds, the exhibition also features abstract photographs from your grandfather’s geological archive: microscopic images of the mineral mica. As with much in your practice, mica reveals itself as a paradox of value. On one hand, it causes buildings to deteriorate when present in construction mixtures. On the other hand, it’s a highly heat-resistant insulator; and aesthetically, it’s used in shimmering cosmetics. Why was it important for you to show these photographs alongside the video work, and what kind of relationship do the images establish with it?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: The inclusion of my grandfather’s microscopic photographs of mica in the exhibition has an unexpected backstory. While researching geological formations in Northern Ireland, I found myself constantly thinking about mica, due to the widely publicised defective building block crisis there, an event by which homes began to crumble because of the use of mica-rich materials. Roadside signs even read ‘Mica is a virus.’ This situation turned mica into a kind of antagonist, even though it’s simply a mineral. The problem wasn’t mica itself, but its improper use in construction mixtures, without regard for its properties. Although mica wasn’t the sole cause of the crisis, it became a symbol of the issue and of the inaction of the Donegal region authorities. This story resonates with broader reflections in my work on the illusion of geological solidity, and on fragility and instability. What appears unmovable can, in fact, be incredibly delicate.

The archival mica photographs taken by my grandfather add yet another layer of representation in the exhibition. These are microscopic, analogue images that capture only fragments, abstracted details that seem to penetrate the inner structure of the rock. As scientific photographs, they offer a perspective I couldn’t achieve with my own camera, a way of looking inside the material. This mode of representation resonates with the visual approach in the video work, which also attempts to peer into the ‘interior’, down to the level of rock micro-organisms. Moreover, the visual character of these mica images, especially considering the ‘virus’ connotation it took on in Northern Ireland, bears a striking resemblance to medical imagery, like cell or virus scans. In this way, the personal (my grandfather’s photographs), the socio-political (the crisis in Ireland), and the visual-philosophical (reflections on interiority and surface) intersect in the exhibition.

Ieva Kotryna Ski, Untitled, 2025. Text on paper

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: I was somewhat surprised by the exhibition title ‘stonewashing’, a term that refers to a denim treatment process designed to accelerate the fabric’s fading and softening, essentially simulating a kind of wear that the wearer themselves never had the chance to create or experience. How did this term enter the vocabulary of this particular exhibition and ultimately become its title?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: The jeans featured in the exhibition serve as a multilayered reference. Initially, my thoughts revolved around materiality in a broad sense, even extending to explorations of dark matter. But jeans entered my creative field from a far more everyday experience: an obsessive search for the perfect pair. What might seem like a banal pursuit evolved into a deeper interest in the fabric itself. As a garment, jeans are highly iconic, embedded with countless cultural references. They also hold a particularly important place in queer history and aesthetics, where workwear became a form of expression of identity and a key element of ‘dyke’ visual culture.

This everyday object also opens up more complex themes. Learning that denim production is one of the most polluting industries, requiring vast amounts of water and chemicals, changed my relationship with the material. This ecological perspective aligns closely with the themes explored in the exhibition: material transformation, erosion, the impact of water and elemental forces. The title ‘stonewashing’ itself comes from the original method used to give jeans a faded, worn look, by washing them with pumice stones. That etymology made the term seem especially fitting, as it ties together the exhibition’s varied references: from the desires embedded in denim to the ongoing transformations of geological (and other) matter.

Deimantė Bulbenkaitė: One of the most compelling leitmotifs in your work for me is the power of the imagination, or, more precisely, the desires that unfold within it in various forms. These desires are often expressed through their near-impossibility, through the slowness of their fulfilment: a beautiful geological metaphor might be continents that drift towards each other at a rate of just a few centimetres a year. Slowly, but they do move closer. What desire do you have for this exhibition?

Ieva Kotryna Ski: Desire, although broad in its definition, often becomes the main driving force both in life and in creative practice. It sparks curiosity, leads to new ideas, and sometimes even evolves into obsession. Desire carries with it a sense of intangibility, a longing for something perhaps not entirely reachable or fully comprehensible. That feeling is closely tied to a continuous search for connection with reality, a search that can grow more complex when living away from one’s home city, under a certain veil of estrangement between oneself and the surrounding world. I’m reminded of the character in John Cassavetes’ film Opening Night who speaks about how, in youth, emotions exist just beneath the surface, so close, and how difficult it becomes to preserve that sensitivity later in life. That resonates with me too: the attempt to find a way to once again fully perceive and feel the world and oneself within it. Regardless of the specific subject matter, even if it’s just rocks, the moment of desire always remains. Because the act of making becomes a way to seek out and rebuild that connection with reality.

The specific desire I have for this exhibition is closely tied to the viewer. As with my other works, my greatest wish is for the exhibition to act as a kind of gateway, one that encourages visitors to travel in thought, to reflect on things they may never have considered before. That’s why I consciously avoid offering overly precise or closed interpretations, because I believe my perspective as an artist is only one among many. What I value far more is hearing and seeing how others interpret the work in their own way. Personally, I find it deeply moving when another artist’s piece stirs emotions in me that I hadn’t yet named, or provokes unexpected thoughts and reflections I couldn’t have predicted. That’s the kind of openness, to new thoughts and sensations, I hope visitors bring with them to the exhibition.

3 microscopic photographs of mica from the archive of geologist Vytautas Narbutas, 12×9 cm, 12×9 cm, 11,5×9 cm

Ieva Kotryna Ski, stonewashing, 2025. Exhibition view at Editorial, Vilnius