This was an encounter between inhabitants and summer residents of Užpaliai, and between participants in the exhibition and visitors. A visit to a town is its rite of public exposure. As a matter of course, questions about neighbourliness, the making of a place, and the making of creative acts in the place, arise. Having received an invitation to the exhibition, the movie The Wicker Man (directed by Robin Hardy, 1973) comes to mind for a second. The thought dissolves imperceptibly in another second. On arrival, I hear silence, and cicadas and tractors buzzing. There are almost no allotments or fences, and many old wooden houses. I see many SUVs and hardworking and caring hands preoccupied in various actions.

In what follows, I present the exhibition ‘Akcija (2)’ that the Užpaliai community put together in their town in the northeast of Lithuania late this summer. Followed by an artist residency, it was the second time around. The scale of the first ‘Akcija’ last year was smaller, and in terms of location it was tighter: eight artists exhibited works in Užpaliai High School. This year, the number of artists increased by one, and, as was said in an opening speech, semi-site-specific pieces were scattered around the town. The main aims of the exhibition remained, to show contemporary art outside the main Lithuanian cities, to create communal bonds with the help of art, and to promote regional tourism. Among the works, a few common threads appeared, namely system thinking and the medium of sound. Here, I try to show that these two threads intertwine.

During the residency, participating artists (Greta Eimulytė, Alanas Gurinas, Liudvikas Kesminas, Denisas Kolomyckis, Barbora Matonytė, Eglė Širvytė, Ona Barbora Šlapšinskaitė) attended talks by three locals: the folklorist Gražina Kadžytė, the phonography and acoustic ecology researcher Audrius Šimkūnas (Sala), and the librarian Vida Juškienė. These three areas of exploration (folklore, sound and town) are partially reflected in the works. During a tour around Užpaliai, Vida Juškienė introduced the group to Marytė. Inspired by her story, Liudvikas Kesminas made the sculpture 2023 A.D. The piece is a medium-scale aluminium pyramid placed on the east side of Marytė’s garden. Introducing the work, Kesminas talked about function. During their meeting, Marytė said that there used to be two synagogues where her garden is now. They were burnt to the ground, and because of the very fact of residing in this place, misfortune haunts her life. The town’s priest suggested putting up a cross on the east side of the garden, while a psychic suggested building a pyramid. In addressing Marytė’s problem, Kesminas built an aluminium pyramid for ‘Akcija (2)’, 50% functional, and 50% aesthetic. Starting the thread of system thinking, I see it as thinking about separate parts of a phenomenon, their interrelations, and a view of the bigger picture. Here, the phenomenon is Užpaliai itself. I am convinced that this thinking can be witnessed in almost every piece. Nevertheless, I see the systems as clearly expressed social, political or economic networks of exploration. With 2023 A.D., it is issues of the artist’s role and beliefs, especially when bearing in mind purged belief systems. Is Kesminas performing the role of a commissioned healer here? The healing intention is hidden in the title: A.D., or Anno Dominus, rather than CE or other combinations.

Liudvikas Kesminas, 2023 A.D. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Hard-working and caring hands spend much time exploring flea markets. Inspired by the experience of exploring the Užpaliai flea market since her teenage years, Ona Barbora Šlapšinskaitė presented a work called I Love Skudurynas (or I Love a Flea Market) shown in the marketplace. Every weekend, a Volkswagen-Transporter type of automobile, or a few, comes to the marketplace filled with bags of second-hand clothes. After unloading their vehicles early in the morning, ‘Tribal nomads become tradespeople, berries are handbags, and mushrooms are heels. Gatherers fill their baskets with clothes.’ These words were written on the front of the I Love Skudurynas stall. The back was marked with a flame motif inspired by graffiti in late 2000s fashion. The silver flame motif, like a community symbol, could be a nod to the marking of territory. The marketplace operates under the rules of trading rather than fighting. Perhaps it is not by chance then that the Užpaliai coat of arms incorporates the slogan ‘Towns grow with the help of trade’. This attention to a social reality, the trade in second-hand clothes, and its interrelation with self-expression or the joy of finding a T-shirt with a funny quote, is what I mean by system thinking. Through various ties, Užpaliai relates to other places. Through economic chains and entrepreneurship, some of the clothes possibly reach the town through the culture of donation in France or the United Kingdom. The clothes are re-sorted: some might even go back to those countries, others reach Užpaliai, while others might spread out along the Korle Lagoon in Accra. The re-sorting of clothes re-sorts symbols as well. Something abstract becomes tribal. In a poetic way, a nomad tribe is born. However, when flicking through the clothes, being in the vortex of this mixing, power, like a silvery or even a bright red flame, seems to be within you. I too love skudurynas.

Ona Barbora Šlapšinskaitė, I Love Skudurynas. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Ona Barbora Šlapšinskaitė, I Love Skudurynas. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Along with system thinking, sound comes to the fore with Denisas Kolomyckis’ installation Bab-ilu, composed of a panel with an abstraction made from a mixture of sand and coal, benches, a cast metal object in the shape of the word ‘virtue’, wires, a satellite dish and antennas brought by locals. The work, referencing the Babel story, was exhibited in the administrative building of the Užpaliai manor. How is the manor’s memory managed? Rebuilt manors in the countryside encourage tourism. They become venues for concerts and theatrical performances, festivals of flowers and gentry cuisine, re-enactment tours, and family celebrations, among other activities. The restored manors make beautiful images of a time gone by as a background for these pursuits. Some host community centres, artist residencies, or places propagating slower living. Historically, Užpaliai used to have a royal manor. The landlords were constantly changing and moving from manor to manor when resources were exhausted. The interior of the manor has been restored as a white cube that directs attention to the objects currently exhibited there. Even if ‘Akcija (2)’ questions this kind of exhibition, choosing this space for a work about multiplicity (the multitude of languages in the story of Babel and people who brought the antennas) and the broadcasting of connection encourages the hope that white walls and wealthy households may become a place for gatherings of different stories and experiences.

Denisas Kolomyckis, Bab-ilu. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Denisas Kolomyckis, Bab-ilu. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

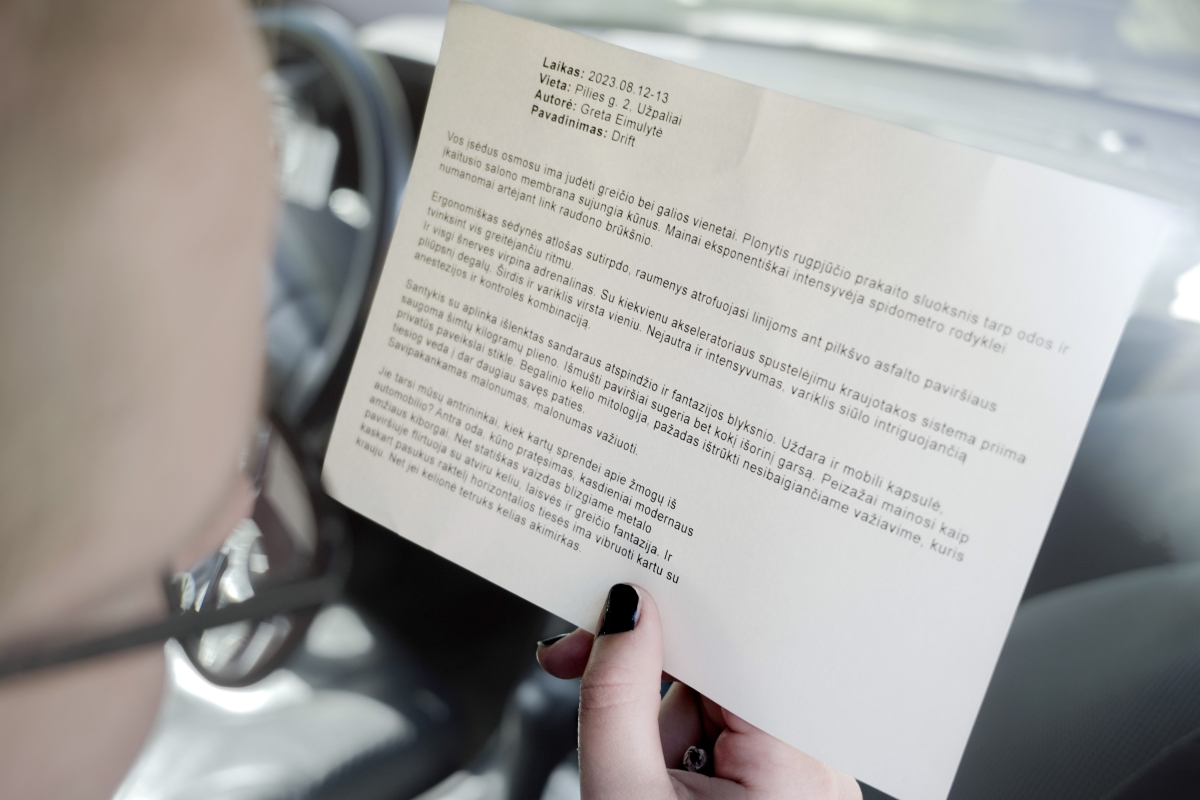

In the piece by Kolomyckis, sound was referenced through the field of imagination. In Greta Eimulytė’s Drift, sound emerges as one of the main parts of the work, while the subject matter points to system thinking. The sound installation, inside a car standing in front of the local grocery store Pauleta, and expanded with an artist’s text, focused on the relationship between the driver and the automobile, and the blurred boundaries of this link. In this case, sound activates internal systems: the pulsating rhythm of the heart accompanies the sound of a car engine. The intertwining of these sounds reminds me of transcorporeality. The framework brings to light the interrelation between the body and the environment, and the latter’s materiality. An example that elaborates on the concept would be the recently discovered microplastics in the human body, which enter the body through food, pores and in other ways. Yet cars are an individualising technology that slowly dissolves the links between the body and the environment. With windows closed and the air conditioning on, it is easy to forget about bodily porosity when speeding on a motorway. The duality of the title, drifting as being slowly carried along and the motorsport, also allows us to see this knot even more closely. The title points to both being in the flow, and, if we were to take the scheme of drifting as a metaphor, oversteering in an upcoming turn with the front and back wheels pointing in opposite directions, losing the grip, and sustaining the momentum. This twisting to maintain inertia, like a paradox, reflects the aspiration of freedom through mobility and its relation to the permeable body and its environment.

Greta Eimulytė, Drift. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Greta Eimulytė, Drift. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

The thread of sound reveals itself best in the last three pieces in the exhibition. In these works, sound either remains the main element or is blended with others. Sound is inevitably bound to a place and its physical characteristics. Some materials reflect sound, others absorb it. In Eglė Širvytė’s piece Invasion, sound took on the shape of recorded folkloric polyphonic songs. Širvytė sang the songs together with the women of Užpaliai, and discussed what to sing and how to pronounce the words. Sound here, shapeshifting into music, song and dialect, explores language that tends to be intertwined with the national identity, which was also the focus of the piece. Meanwhile, Barbora Matonytė’s To the Bone, continuing the theme of trade, was exhibited in the Pauleta shop, and offered a chance to have a chat with skulls. The conversation, however, was one-sided since the skulls repeated like parrots what the visitor had said. One skull was placed beside the cashier and became a daily companion to trading. The sound fusing with other sounds in the well-frequented place reflected like a mirror the social bonds unfolding every day in the shop. In this way, it rubbed smoother the non-place charge of the shop. People became less anonymous, striking up new conversations and indulging in banter, while the shop became less of a transitory space. Through both Invasion and To the Bone, sound incited social connections between the listeners and participants in the installations.

Eglė Širvytė, Invasion. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Eglė Širvytė, Invasion. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Barbora Matonytė, To the Bone. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Barbora Matonytė, To the Bone. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

The sound sculpture by Alanas Gurinas A Slightly Light Tone, exhibited in a former bar, focused on the materiality of sound. The weight of sacks with sand stretched sheets of paper. Just before the moment the sheets of paper start to split, they also start to make a sound. Small engines quivering the sheets increased the pre-splitting sound of the paper. These sounding objects were hung in the main area of an abandoned bar, which is now a building site. The unpolished and not concreted-over or primed details of the building exposed it as a piece of clothing with the seams inside-out. In this room, time slowed down, and the gaze turned to the physical aspects of the place. By getting to know a place through sound, one might empathise with, for example, bats and their sense of echolocation. Sound vibrations travel neurologically through the hearing ear and the whole body, and acquire the shape of a certain cultural meaning. Historic narratives about Užpaliai fray, and the lived experience seems to come closer. What came near this time was an extended strip of sunset in a slightly light tone and rising dust.

Alanas Gurinas, A Slightly Light Tone. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

Alanas Gurinas, A Slightly Light Tone. Photo: Alanas Gurinas.

System thinking and sound are quite different categories, one pointing to content, and the other to form. Both system thinking and sound create circumstances in which one can embrace a larger-scale view. With sound, it is the appeal to more senses than just sight. The dialogue between the artists and Užpaliai touched on many topics. A retold conversation has more structure than the conversation itself. Therefore, the drawers of the categorisation in this piece could be opened simultaneously or taken off the rails and put into a new order. Hopefully, hard-working and caring hands will continue running this project, and the unofficial title of ‘Akcija’ might turn to ‘Užpaliai Sculpture Projects’ (after ‘Skulptur Projekte Münster’), with the hope that the frequency of the project will not then be measured in decades.

The project Betarpiškos erdvės is funded by the Lithuanian Council for Culture.