Comparison is the thief of joy, they say. I promise I won’t steal your joy by comparing the distinct national pavilions of the three Baltic States (although promises are made to be broken). This year’s International Venice Art Biennale, curated by New York-based Cecilia Alemani, fed the art-hungry crowd with ‘The Milk of Dreams’, an exhibition with its title taken from Leonora Carrington’s children’s book, which sought not only to rewrite the Surrealist canon, but also to take Surrealist visions as a starting point to explore transformations of bodies, nature, gender and politics in a broader sense. Rich in its research and the amount of works, the show offered an unprecedented number of pieces made by women, people of colour, non-binary, colonised and indigenous artists, this way making a gesture of remorse for all the injustice brought by colonialist and capitalist exploitation, and at the same time celebrating the fertile knowledge and imagination brought by these creators into an otherwise white patriarchal world.

The Latvian and Estonian pavilions responded to the topic of this year’s biennale quite closely: both exhibitions featured female artists with feminist and post-colonial installations; the Lithuanian pavilion less so, focusing rather on ecology, globalisation, and the strategies of start-ups.

Unlike in previous years, this time the Estonian pavilion could be found and visited quite effortlessly: it settled quite easily into the Gerrit Rietveld-designed Dutch pavilion, right on the gravel path to the main exhibition building. The Netherlands has broken with over 60 years of tradition by formally handing over to Estonia its precious exhibition space, and presenting the immersive installation by Melanie Bonajo at La Chiesetta della Misericordi, quite a walk from the buzz of the main biennale. Curated by Corina L. Apostol, the exhibition ‘Orchidelirium’ explored the controversial life and work of Emilie Rosalie Saal, a colonial botanical artist and world traveller, through the work of Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi, made in response to Saal’s legacy. The controversy starts right at the entrance: one is stopped at the main entrance, to be directed through the back door like a servant. The unfair game of power structures was also demonstrated in the film trilogy Rip-off, Shelter and Thirst by Kristina Norman, as well as in the kinetic sculpture by Bita Razavi, a reference to ‘kratt’, an enslaved magical creature from Estonian mythology, producing botanical drawings. Both humans and machines were subjected to the Western desire for the ‘exotic’.

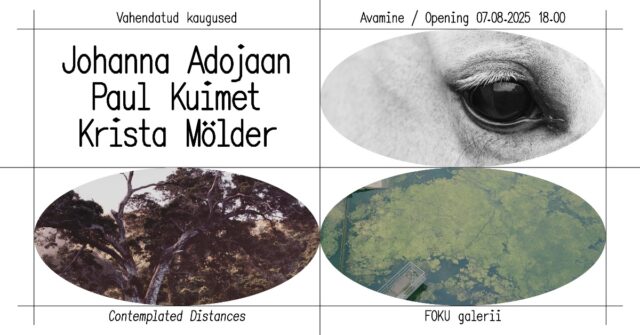

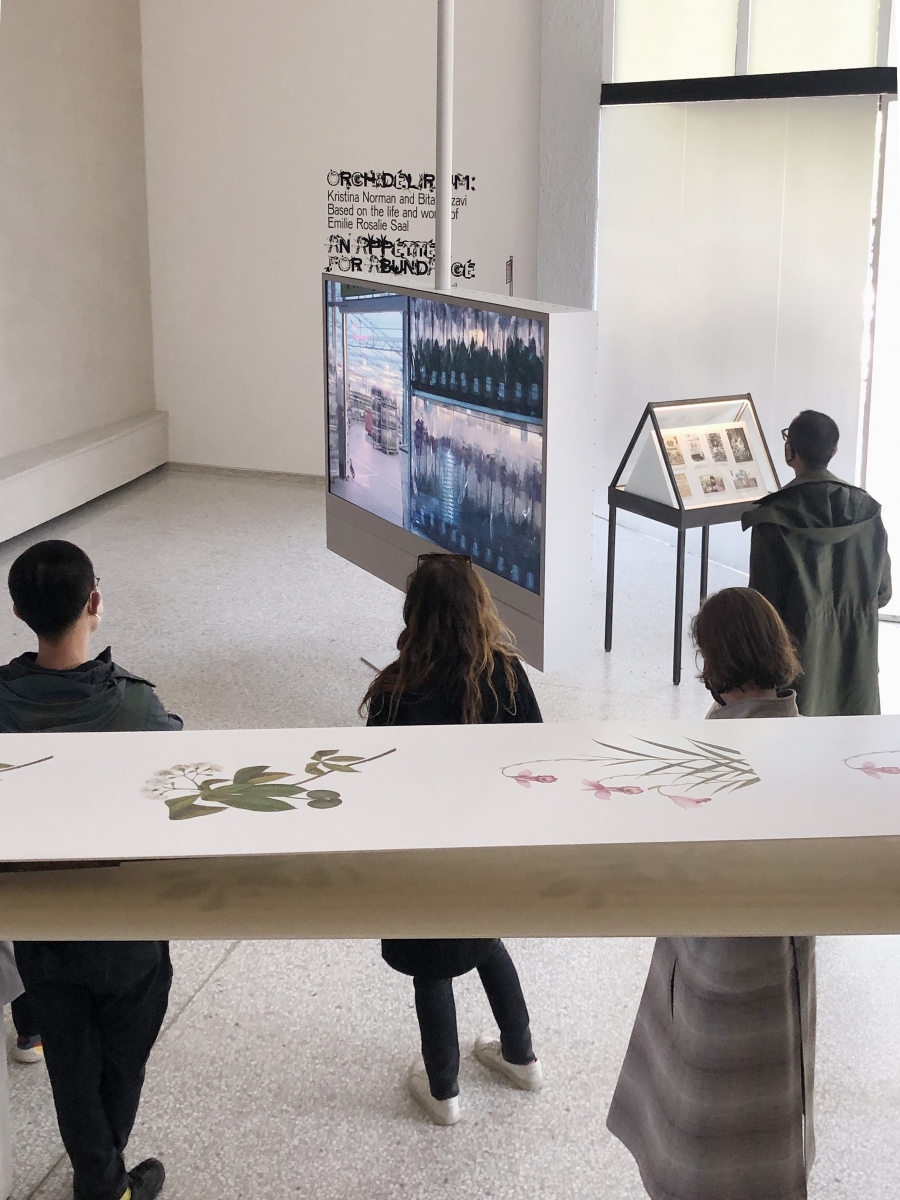

Estonian pavilion. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance by Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi. Curator: Corina L. Apostol. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Emilie Rosalie Saal was a producer and consumer of the orchidelirium of 19th-century Europe and the United States: while living with her husband, the famous Estonian writer, photographer and topographer Andres Saal in Java in Indonesia, which was then a Dutch (!) colony between 1899 and 1920, she made detailed drawings of rare orchids. Widely appreciated in the West, her drawings and photographs depicted rare plants against abstract backgrounds, thus erasing their place of origin, the indigenous knowledge razed by the colonists. As archive images displayed in the pavilion’s glass display cases reveal, Saal was carried in a carriage on the shoulders of indigenous people on her expeditions to draw rare plants. The archives give the context of the botanic-colonial relationship in a wide spectrum across space and time, and yet sometimes the textual information accompanying the images was a little too didactic, as if doing the (self-)moralising work for the viewer itself. The images range from women from Indonesia who were put on display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, to luxurious interiors of Saal’s house in Jakarta, to Indonesia’s first lady Siti Hartinah Soeharto (1923–1996), who created a lush garden of tropical orchids. The enclosure was built by displacing communities in Jakarta, despite local protests. Oppression knows no bounds of space and time.

Emilie Rosalie Saal’s artistic work was also for a long time overshadowed by her husband’s fame, while she was seen as just a housewife. Kristina Normane’s films tap into these complicated and enmeshed layers of the orchidelirium, the colonial gaze, the subjugated housewife, and the plants themselves. Presented on three screens around the room, the videos act as semi-performative events in which hallucinating female sexuality is followed by the amused gaze of strangers watching a caged (white) woman, while the third screen takes you to an orchid greenhouse in which an ecstatic, crazed face painted in white repeatedly appears and disappears. The films are occasionally interrupted by a performance film by Eko Supriyanto.

However, the overall powerful, conceptual, historical and political framework of the pavilion, the topics in the films and the elegant display did not translate into an immersive experience, which one would expect from delirium, explored in the show. It felt a little academic, quite the opposite of the frenzied and sexualised hallucinations presented in the videos.

Estonian pavilion. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance by Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi. Curator: Corina L. Apostol. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

If the Estonian pavilion felt a little austere, the Latvian one was overwhelming. Curated by Andra Silapētere and Solvita Krese, and presented at the Arsenale, the installation Selling Water by the River was conceived by Skuja Braden, an artistic duo born in 1999, with Ingūna Skuja from Latvia and Melissa D. Braden from California in the USA. As the title itself suggests – abundance and fluids dominate the pavilion. Not only it teaches us to see what we already have (as the original meaning of the title, coming from an old Japanese saying, evokes), but also refers to the ideas of Hydrofeminism, in which water is a shared quality among beings and bodies. Water that erases boundaries between the self and the ‘other’.

Partners also in life, the two artists reminded us once again that the personal is political, especially if you live in a region like ours: Latvia and Lithuania still do not recognise same-sex marriage, or any form of same-sex partnership. Skuja Braden generously invites you into their home. A home made of porcelain. An abundance of porcelain, scattered on the floor, placed on tables, hanging on walls and on the ceiling, vases, plates, lamps and altars, all pieces of porcelain in various shapes, colours and painted motifs. In the skilled hands of the artists, seemingly mundane objects such as vases or plates became vessels to be filled with political content. The flood of porcelain was structured around smaller pools, the key elements in a home: the Washroom (for corporeal fluids), the Dining Table (for laughs and fights over politics), the Studio/Kitchen (for creative productivity), the Altar (for otherworldliness), the Bedroom (for you-know-what), and Vanity (for careful self-reflection).

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

If you have ever worked together as well as being partners in life, and tried to unravel those two knots, you know it’s a mess. In Skuja Braden’s installation, this complex muddle acquires even more components from the fields of (regional) politics, religion and sexuality. A large vase with Putin’s face painted on it stands on the floor, a light made of penises over the table, statues of Buddha, vases with Geishas, and a fountain of snakes: the eyes quickly get lost in this lushness. Here the delirium finally hits. What stops us from fully submerging in the warm waters of the fluid dizziness of life is the aesthetics; while the artists consciously play with the decorative, it often slides too far into kitsch, leaving no room for thought. At one point, you get the feeling of being force-fed Pavlova’s cake in an enormous quantities.

There was a bit of mud in the Lithuanian pavilion too, but less than you would expect for an experimental seaweed factory. Located in one of the last remaining ungentrified piazzas in Venice’s Castello district, the pavilion ‘Gut Feeling’, divided into two spaces opposite each other, presented the multifaceted practice of Robertas Narkus, and was curated by Neringa Bumblienė. Astonishingly stylish and well executed, the show was a real feast for the eyes: built by a talented team, consisting of a lighting artist (Martynas Kazimierėnas), graphic designers (Nerijus Rimkus and Vytautas Volbekas), architectural advice from Isora x Lozuraityte Studio for Architecture, as well as fellow artists, the two spaces attracted the attention of passers-by with their beautifully orchestrated coloured lights, textures, architectural planes and neon signs. While one store-front space was transformed into a fictional laboratory/factory for fermented goods to be made from seaweed, the other shop window-like showroom/reception area invited us into a world of abstract values detached from material goods, into a world of meaningless symbols and numbers that dominate today’s financial economy. Both of the spaces breathed with a sense of a post-apocalypse or abandonment: in the factory room, an old computer monitor as well as some of the walls were covered in thick layers of seaweed, while in the ‘commercial’ space wires and lamps were hanging loosely from the ceiling, snaking around the floor in viscous patterns.

Lithuanian pavilion. Gut Feeling by Robertas Narkus. Curator: Neringa Bumblienė. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

The initial promise of the pavilion was quite ambitious: it attempted to convert the entire street into an extended artistic project involving locals and small businesses. To create ‘social sculpture’, in the words of the press release. The aspiration went further by exploring the potential of seaweed to revolutionise the food industry, and this way offer a solution to the growing issue of the global food supply. Elon Muskian goals quickly ran up against a material and social wall: apart from a bar nearby where all the Lithuanian art gang spent their opening nights, the locals seemed less enthusiastic about getting involved (hard cheese, Venetians), while the nutritious and invasive seaweed Undaria pinnatifida growing in the waters around Venice appeared to be poisonous. Hence, grand ambitions for now had to be conserved in empty cans rotating around an automated assembly line in the pavilion.

Failure, however, was already written into the project itself, since at the beginning, on one hand, the artist toyed with idealistic aspirations to save the world, while on the other knowing its pure impossibility by means of artistic practice or start-up economics. This kind of slippery ambiguity is a conscious strategy of Narkus, who flirts with and directly explores various contemporary economic structures. There was plenty of humour and tongue-in-cheek appropriations of digital business presentation tools to build three-dimensional comic sculptures. Even the star–chef and fermentation researcher David Zilber undressed to bath in foam and algae and give a short presentation on globalisation, biology and economics. Nothing at all and yet everything was meant to be taken seriously. Where does it leave us? With a lush Instagram shot of the pavilion, and an empty can of the imaginary product of an experimental seaweed factory in the hand? ‘Gut Feeling’ reminds us that our ‘rational’ decisions might as well be made by the bacteria in our guts, rather than our ‘clear’ minds. We need to treat them well in order not to fail and step down from the pedestal as the only true decision makers. Perhaps the current state of the pavilion are just the first steps in this experiment, and the social sculpture and the physical fermented products will gradually be built during the long months of the biennale. Fermentation, after all, is a lively process.

Until then, we have enough reserves from the ‘Milk of Dreams’ exhibition. So much to digest!

Lithuanian pavilion. Gut Feeling by Robertas Narkus. Curator: Neringa Bumblienė. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Lithuanian pavilion. Gut Feeling by Robertas Narkus. Curator: Neringa Bumblienė. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Lithuanian pavilion. Gut Feeling by Robertas Narkus. Curator: Neringa Bumblienė. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Lithuanian pavilion. Gut Feeling by Robertas Narkus. Curator: Neringa Bumblienė. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Latvian pavilion. Selling Water by the River by Skuja Braden. Curators: Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Estonian pavilion. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance by Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi. Curator: Corina L. Apostol. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong

Estonian pavilion. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance by Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi. Curator: Corina L. Apostol. Venice Biennale, 2022. Photo: Echo Gone Wrong