One of the most distinctive characteristics of photography is that it isolates single moments in time. The captured moment remains untouched by age, it transcends the era of its origin, and irradiates us with the emission of its timelessness. The more fleeting the moment, the more important it seems to encapsulate it. Photographers energise the isolation and extraction of moments, and not the documentation of the total and entire truth, whatever that may be. Ultimately, the impressive result of the photographic undertaking is to give us the sense that we are able to hold the entire world in our hands, as a compilation of pictures.

Surprisingly, not all art was meant to be seen. Francisco Goya painted Saturn Devouring his Son on a wall inside his house without the intention of the public ever seeing it. This painting may reflect the artist’s state of mind when he was descending into increasing isolation and the consequent trauma. Being under full or partial lockdown these last couple of years due to the Covid-19 pandemic has left millions feeling mentally exhausted and emotionally overwhelmed. But every cloud has a silver lining: the collective experience inspired many riveting projects. Even confined in their apartments and studios, artists unleashed their creativity in advanced ways, so it is no wonder that the ever-growing Riga Photography Biennial has chosen to focus on the theme of isolation this year (alongside special attention to enciphering the contemporary image).

The exhibition ‘Screen Age III: Still Life’ curated by Inga Brūvere and Marie Sjøvold at Riga Art Space continues a series from 2018 that examines how the traditional genres of portraiture, landscape and still-life have changed beyond recognition in the new era of technology. In a sense, the still-life has been reborn through vanity posts on social media and the decadence of advertising culture. We can hardly speak about objects without venturing into speculation about their owners, the subjects. In that sense, the still-life becomes an extension of the portrait. In the video collage Displacement Behaviour by Charles Richardson, human busts are reimagined as inside-out, transparent, yet irreparably hollow, modern nomads wearing everything they own. It recalls the Junk People in the cult classic movie Labyrinth attempting to make the heroine forget her quest by plying her with her own possessions. The artist expresses the idea that if a person’s consumption determines their identity and social position in a consumerist society, then so does their waste. Indeed, in the modern world, wasteful consumption has become almost compulsory.

Human anxiety about resource accumulation often degenerates into pathological hoarding, not only at the level of separate individuals, but also at the level of corporations and governments. It seems somewhat ludicrous that now almost every European country has displays of ancient artefacts in their museums: what is it, if not a once-fashionable collection of exotic mementoes that may now be seen as shameful colonialist behaviour. Marianne Bjørn’s Epitaph explores how managed supremacy, operating on the premise of preservation and appreciation, used to exploit foreign lands like a deposit to be mined in order to extract the tangible objects of civilisations that no longer exist. Now, of course, the original objects themselves are long gone, perhaps lost in the black market of careless greed. What is left is the actual nature morte: some photographed objects have been cast in new forms, creating new myths that break up the colossal world of the abundance of objects previously so formidably sustained by the clear functionality of either everyday life or religious rites. The deconstructed historical reality poses the question ‘Who will be the legitimate inheritors of loss and oblivion when inheriting goods is not possible any more?’

Since the world’s earliest reliably dated daguerreotype still-life was taken in 1837, this form of photography has been a great way for artists to practise their craft and search for their own aesthetic feel. The photography series ‘21st-Century Still-Life’ by Vilma Pinenoff shows compositions made from tablecloths with prints of flowers and fruit which not only imitate 17th-century paintings, but also show how it takes more time and resources to create counterfeit objects, since accepting authentic objects seems too passé for modern man. Rather than the fleeting nature of innate beauty, kitschy oilcloth offers us the aesthetics of fakery, of objects that do not wither, do not require water or sunlight, and do not die. Yet another type of artificial object that stimulates our senses without giving us any real or symbolic nutrition. The artist uses plastic material that requires hundreds of years to deteriorate to emphasise the opposition of immortality to temporality, which may be impractical but is much more beautiful in its delicacy. Progressively overwhelmed by reproductions, we are reduced to playing with them instead of utilising them or connecting with them.

We live in an era of soundbites and snapshots, when objects try not to wake up but rather to obscure the memory. Perhaps the only counterweight to this kind of collective oblivion is an authentic relationship. The internet can already offer AI filters that can take static pictures and seemingly bring their subjects back to life. It is hard to say if adding generic smiles and animated movements of the brow to images of the dead is more comforting or offensive to mourners. At least for now it is impossible to monetise memories (although there are studies investigating whether or not autobiographical advertising can prompt consumers to imagine their childhood experiences so that their memories become more consistent with images evoked in advertising). The installation Sharing Tent by Sara Skorgan Teigen is an attempt to connect with a deceased loved one. By creating a separate place for her grief, the artist awakens the genetic memory, perhaps even pre-Christian traditions of saying goodbye to the dead. The photograph of a crying Marcel Marceau in his full mime attire inside the tent possibly represents humanity with all the faces we can possess as a collective.

Paulius Petraitis’ Solo Exhibition ‘Surfaces’ at the ISSP Gallery. Photo: Madara Gritāne

Walking through museums of old art, one could exclaim ‘This is in fact photography before photography.’ The invention of photography in the early 19th century served as an inspiration for movements like Naturalism and Impressionism. In the first half of the 20th century, the visual arts had to revive themselves through the ambitious challenges of abstraction, pure form and colour, leaving the duty of making visual documentation to photographers. The exhibition ‘Measured Perspectives’ of work by the Dutch visual artist Katja Mater and the American photographer Erin O’Keefe (curated by Paulius Petraitis) applies the optical ambivalence intrinsic to images to highlight the fact that apparently constant viewpoints are carefully composed and are not just dynamic and intuitive. The surfaces of the imagination hold back a stranger’s gaze. The gaze needs distance, both spatial and temporal. Only when viewed from a distance can the totality of process-based experimentation be seen; the supposedly abstract painting reveals itself to be a photograph. Mater’s video piece Threefold reinforces this narrative. The video is like three-voiced painting polyphony with a 30-second delay. The piece seems to question the meaning of the Sisyphus-like painter’s practice if in the end everything is turned to pitch black. Metaphorical and physical darkness means both the shortness of existence and even the perpetual ignorance of spectators.

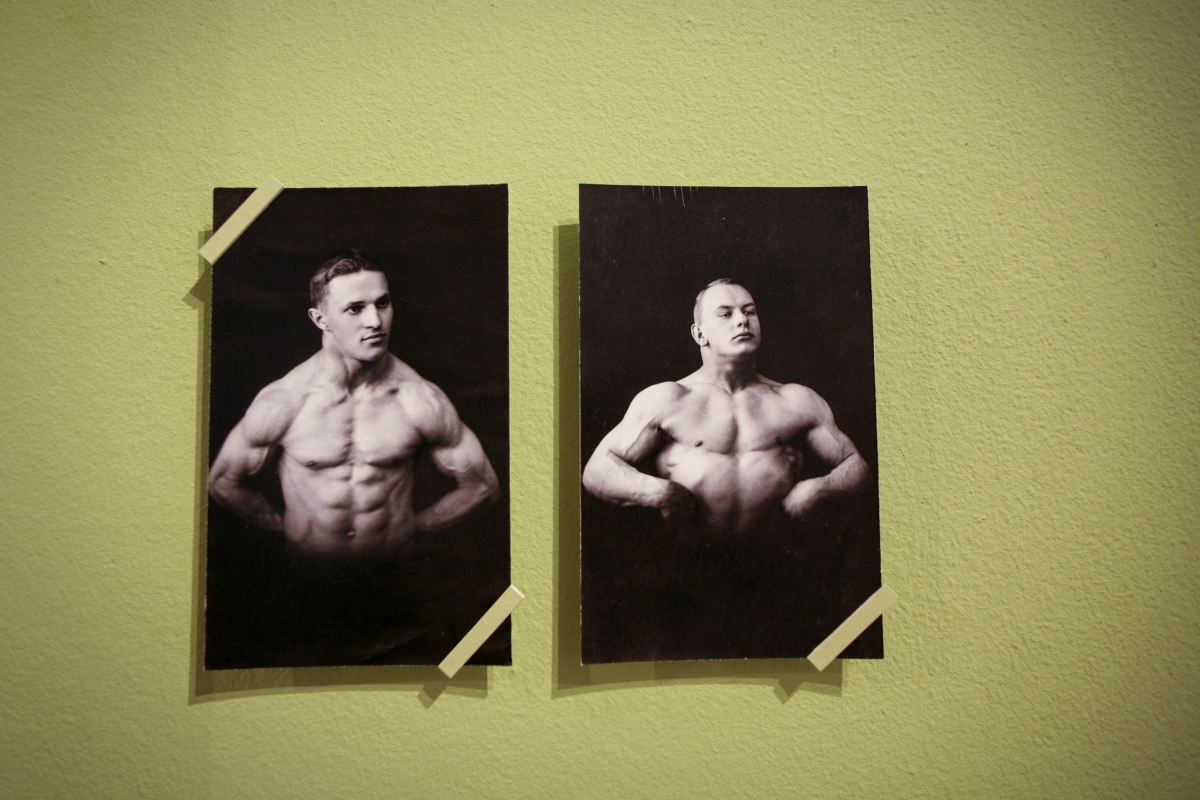

There is a nice synchronisation of the aforementioned film and the video piece displayed in the exhibition ‘The Photo Album – A Subjective Narrative’ at the Latvian Museum of Photography (curator Baiba Tetere, artist Krišs Salmanis). Cinematography that conveys the past through three lines of action still connects the eye into a unanimous relationship between three different photographers, Vilis Rīdzenieks (1884–1962), Alfrēds Polis (1894–1975) and Roberts Johansons (1877–1959). Zooming in on certain details, gently touching the album’s pages, and caressing the photographs’ corners, creates a special intimacy and familiarity with the subject matter. In the reality of contemporary photographic art, saturated with performativity and installations, old photographs from the first half of the 20th century look refreshing and honest. There is nothing sadder than photographs abruptly ripped from an album.

Riga Photography Biennial 2022. View from the exhibition ‘The Photo Album – A Subjective Narrative’. Photo: Rūta Kalmuka

Riga Photography Biennial 2022. View from the exhibition ‘The Photo Album – A Subjective Narrative’. Photo: Rūta Kalmuka

Confusion accompanies the relationship between sight and vision in relation to experiences of certainty and vulnerability. To simply see is quite different to being a spectator. The unique phenomenon of photography allows us a certain unapologetically voyeuristic, and yet at the same time empathic, experience that triggers feelings connected to both the photographer and his subjects. Paulius Petraitis’ solo exhibition ‘Surfaces’ at the ISSP Gallery prefers to highlight the surface ‘appearance’ of photography, to connect to its hidden structures or the essence of the medium the specific features of the physical photograph itself. Photography is for ever cursed to depict either the factual reality or something that does not exist, while risking nonetheless bringing it to life anyway. Reality becomes unsteady when we try to pursue it too closely, with too much attention to detail. Through media such as photography, new copies of the real can be created. Does that mean the original is no longer necessary? In a way, the disappearance of the object would reinforce its perceived importance. It becomes a reality in itself, the fixation on the lost object creates a new ritual of longing and searching; but accidentally pulling back the curtain and revealing the Wizard to be just a man too early in the play can scare the audience away. The surrealist photographer Claude Cahun famously said about his work: ‘Under this mask, another mask. I will never be finished removing all these faces.’ Photography allows you to peel off layers of reality like an onion. The final layer is photography’s diversion, constantly concealing the objective process by staging the opposite. The inverted world becomes something intimate and warm: who is to say that the way we see the world is superior to the perception of bees or whales?

The outdoor project ‘Echo’ by the Latvian artist Kristīne Krauze-Slucka (curated by Anete Skuja) can be seen at ten public transport stops in different Riga districts. The visual works exhibited at the stops are supplemented with QR codes, which take the viewer to a robotic voice reading short extracts from The Machine Stops (1909) by the English writer E.M. Forster, which are hauntingly accurate representations of today’s or near future world. The visual core of the project contains chlorophyll images created on organic plant leaves obtained from natural sunlight. Technology may soon create a reality that will seemingly look even more real than the natural world. It is speculated that even if we were living in a simulation right now, we would not be able to see the difference anyway.

Project ‘Echo’ by Kristīne Krauze-Slucka. Photo: Madara Gritāne

Although to many the pandemic period meant limited communication with loved ones, and various disruptions to daily life, there were some people who secretly rejoiced in surviving the apocalyptic excitement. It might be that a whole generation who grew up on popular end-of-world books, movies and computer games found this extreme situation tantalising rather than traumatising. It could even be explained as a symptom of the ‘main character syndrome’ (a term popularised on social media to describe self-centred people). Experts say that this syndrome is usually a response to a feeling of not having control of one’s life. Surviving times of exceptional crisis gives one the right to tell future generations about extraordinary experiences. Some dream of utopias that would be dystopian to others.

In search of the abstract moment, i.e. tangible invisibility, artists must sacrifice their own visibility (on the real, imaginary or symbolic plane of existence). The topological composition of the whole Biennial can be imagined as a transition from a two-dimensional plane to a three-dimensional existence and back. In various exhibitions in the Riga Photography Biennial, photography reinvents itself through many materials in various multimedia projects. There are so many media at play, but photography is still rightfully viewed as not only the main predecessor of the lot, but also as a constant source of renewal and inspiration. As a continuation of our gaze, or even the presence of the whole body, photography continues to amaze us with its documentary and artistic qualities, which are especially evident when combined with other media. I think many artists would agree that their main interest is not in catching the perfect picture. All they want is a living record of a fictitious reality or a factual illusion. Both the seductive and voyeuristic features of photography demand constantly recommencing forms of image literacy. Asking ‘What does it mean to look at this photograph?’ emerges as much more important than just analysing the elusive meaning of the image itself. The strong points of the Riga Photography Biennial arise out of an immense set of moving variables: a diverse group of artists, captivating topics, and a focus on the analysis of visual culture. All this makes the event highly anticipated and promises many immersive experiences. Photography as a mirror of life, and photography as a mirror of art, face each other, reflections repeatedly bounce off their surfaces and form new collective representations of both. We humans are both the light source and the reflector.

Riga Photography Biennial 2022 main event, the exhibition ‘Screen Age III: Still Life’

April 22 – June 12 | Riga Art Space, Kungu St 3, Riga

Exhibition ‘Measured Perspectives’

April 22 – June 12 | Riga Art Space, Kungu St 3, Riga

Exhibition ‘The Photo Album – A Subjective Narrative’

May 13 – September 11 | Latvian Museum of Photography, Mārstaļu St 8 (entrance from Alksnāju St), Riga

Paulius Petraitis’ solo exhibition ‘Surfaces’

May 20 – July 3 | ISSP Gallery, Berga Bazārs, Marijas St 13, Riga

Outdoor project ‘Echo’

June 6 – 19 | Riga public transport stops