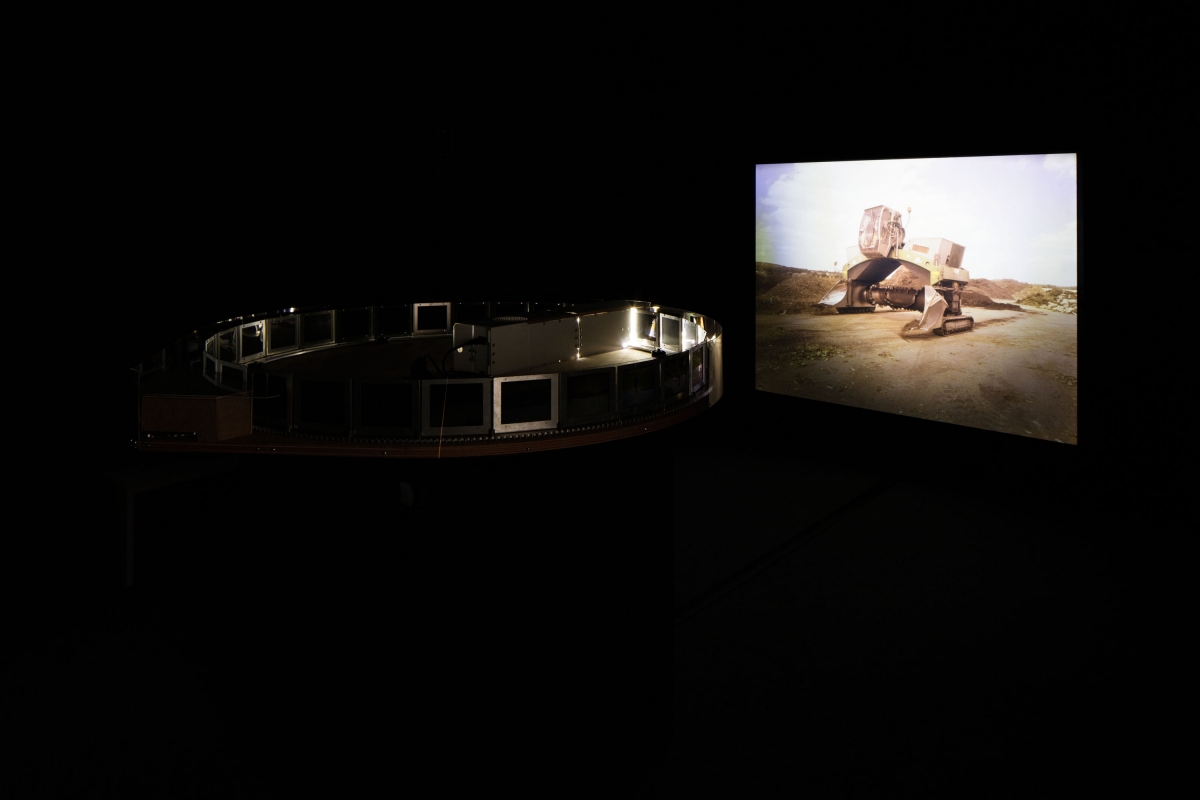

Example of current interest in humans & non humans. 2016. Photo: Christophe Leclercq

“To Hybridity … and Beyond!”[1]

In We have never been Modern[2], Bruno Latour refers to the term “hybrids” to emphasise their proliferation, in contradiction with the domains defined in the Modern Constitution, which distinguishes nature and culture, object and subject, etc. While working on the project An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (2011-2016), we were struck by the proliferation of the recognition of hybrids, humans and non humans in particular, both in the sciences and the arts. Indeed, the attempt to banish anthropocentrism through accounts of non-human entities, and what has been wrongly called “the ontological turn” in philosophical anthropology[3], has spread notably to the contemporary art world[4].

The relation between human and non human entities is highly connected to the mode of existence [NET] for network. In An Inquiry into the Modes of Existence, the term ‘network’, is indeed understood as ‘a movement that records […] the whole series of heterogeneous elements necessary for the completion of a course of action’[5]. As such, it is considered principally as an important step in ignoring the modern division between nature and culture. But for Latour it seems less important to focus on hybridity than on agencies and the issues associated with the political task: the composition of a common world.

The ‘thought exhibition’, Reset Modernity! (ZKM, Karlsruhe[6]), is thus an opportunity not only to remind ourselves of the methodology of relocalising which is at the heart of Actor-Network Theory, but to show also how important it is to renew our concept of nature and responsibility in a period of ecological mutation (or the “New Climatic Regime” in Latour’s parlance). It is also an opportunity to further consider the geo-political orientation of Latour’s recent work[7] and his current interest in Gaia, the ‘Critical Zones’ – his new field work – and the redefinition of the notion of territory. Resetting modernity is therefore not only a matter of becoming sensitive to this new situation, it also consists in renewing our abstractions in order to escape modern dualisms such as global/local, nature/culture, subject/object which have determined a large part of our mental organization, and especially our concept of politics[8].

1. Reset Modernity! From Hybridity to associationism

Contemporary allegory: the Modern Express rescued by Centaurus! 2016.

The exhibition Reset Modernity! can be considered as a kind of prequel to a reading of An Inquiry into the Modes of Existence, rather than a exhibition to conclude this five-year project (2011-2016). To the question “Why should we reset modernity?”, Latour answered: “Because after the reset those who have never been modern may at last register positively ambiguous signals”. Reset modernity is understood as becoming sensitive again to the situation. This Gedankenausstellung – a thought exhibition[9] – and its catalogue are therefore divided into a certain number of procedures that the spectator is invited to follow, with the aim of opening doors to the possibility of renewing our abstractions or concepts[10].

In order to focus on the core concepts of nature and hybrids highlighted in the symposium “Hybridscapes”, we will pay attention here to the four following procedures: “Relocalizing the global”, and its methodology which localises and therefore focusses attention on entities; “Without the World or Within”, which challenges the very modern concept of nature; “Sharing Responsibility: Farewell to the Sublime”, a proposal for reconsidering responsibility; and the redefinition of the concept of territory in “From Lands to Disputed Territories”.

Answering the question, “What is the place of the non-human in the exhibition?”, Latour moves the focus from hybridity between human and non-human to associationism[11] :

“The audience is currently appropriating this really obvious idea about the non-human. This has been the subject of ecology ever since the beginning, but it also implies a rewriting of all philosophy and in particular a rewriting of a large part of the philosophy of science […]. About animals, for example, I have very little to say, since the animal is no subcategory of the non-human. I make no borders around the question about animals, neither around the questions about humans by the way. Otherwise, meat is a question I am very interested in. I concentrate more on the animal sub-categories; not on the animal as an organism, but on parts of animals. A steak is something I better understand. I am an associationist, like my master Gabriel Tarde; I relate to sub-individual entities.”[12]

Latour seems reluctant to take the two terms ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ for granted, as ready-made concepts or frozen categories – in a manner that would still correspond to the dualist modern way of thinking. In other words, the only recognition of humans and non-humans will not help us that much in renewing our abstractions.

2. ’Relocalizing the Global’ or localising and therefore focussing attention

The first procedure of the exhibition, “Relocalizing the Global”, invites visitors to adopt a critical attitude to what seems to be a closed entity:

“Every time someone confronts the observer with the existence of an impenetrable boundary, she will insist on treating the case like a network of the [NET] type, and she will define the list, specific in every instance, of the beings that will be said to have been associated, mobilized, enrolled, translated, in order to participate in the situation. There will be as many lists as there are situations. (AIME)”

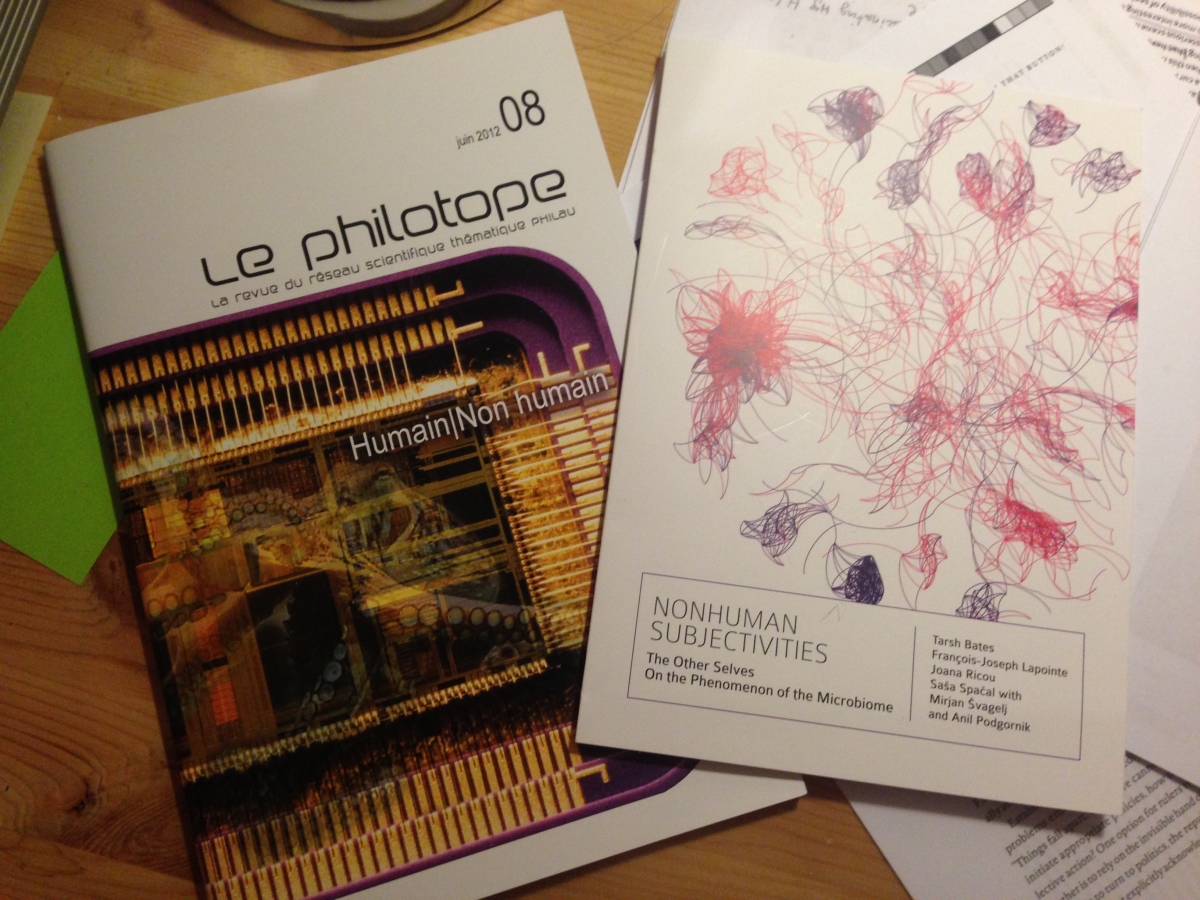

Part of the documentary section of this procedure, Hermant and Latour’s Paris Invisible City, confronts the “panopticon” (the pretension of being all-seeing) with “oligopticon”: “We thus have the choice: either the oligopticons and their traverses, or fixed, blind viewpoints. The total view [the panopticon] is also, literally, the view from nowhere.”[13]. Examples of this pretension of total views are Powers of Ten by the Eames Office or the Leicester Square Panorama. To relocalize what is supposed to be global consists of localising and therefore focussing attention: making visible the different associated actors and their instruments involved in a specific situation (see for instance the making of Powers of Ten).

Documentary station A. Reset Modernity! ZKM, Karsruhe, Germany, 2016. Research: AIME Team Realization: Claude Marzotto and Maia Sambonet (òbelo). Photo: Jonas Zilius.

Paris Invisible City (Bruno Latour and Emilie Hermant. Paris, ville invisible. Paris: La Découverte, 1998.)

Robert Mitchell. Section of the Rotunda, Leicester Square, in which is exhibited the Panorama. 1801.

Operating in the same way, Armin Linke’s film, Alpi, shows how the landscape of these famous mountains is designed, calling into question the idea of a Nature untouched by humans. Linke contradicts our expectation of having a full overview of the mountains, multiplying oligopticons instead:

“Armin’s solution: to reconstitute the series of originally disconnected locations, from which “the Alps” are made visible. You are not likely to see the Alps from above, from the outside; […]. Rather, you are going to visit the laboratories, the tourist board meetings, the military checkpoints, the national weather stations, and even the museums where paintings of snow-capped summits are on display; in short, all the insides into which the ever elusive outsides are absorbed. With Armin, it is as though actor-network theory had been invented only to provide his work with a guiding thread. “Localizing the global” could serve as a description of both the field of science studies and the archive of this photographer of connection.”[14]

In the same way that Paris is an invisible city, we could say that the Alps are invisible mountains! There is no outside from which we could get a “more” realistic overview.

3. Reinstituting Nature in the age of ecological crisis

The second procedure, “Without the World or Within”, proposes to reset our relations with the world. We focus here on how the modern staging of a subject facing an object (a spectator and a scene) has been enacted both in art and the sciences. Here, resetting modernity not only corresponds to a feeling that there is no outside, but also leads us to reconsider and reinstitute the concept of Nature. Due to the ecological crisis, the Modern “institution of a universal Nature allowing the determination of rational solutions”[15] based on the “bifurcation of Nature”[16] (Whitehead), does not work anymore. Nature is not a static background for human (cultural) activities. As Cyril Neyrat wrote, “In 1895, the first spectators of Le Déjeuner de bébé were not moved by the sketch of daily bourgeois life in the Lumière family so much as the quiet rustle of vegetation in the background: inside the image, living nature”[17].

Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor. Leviathan. 2012. 1-channel video, HD, color, 5.1 surround sound, 87 min. Reset Modernity! ZKM, Karsruhe, Germany, 2016. Photo: Jonas Zilius.

Leviathan, a film by Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor about fishing in dangerous waters off the east coast of the United States, provides a more realistic view of this situation. Latour observes “a shift in the role, focus, and position of the gaze”. “The attempt by those authors who call themselves adept at ‘sensory ethnography’ is to start to really register the world sideways by multiplying the sensors and the positions of the cameras. Not to obtain a more totalising view, not by breaking the traditional face-to-face of object and subject, but by “ignoring it” altogether and literally moving “sideways” within the flow of experience. The film is a completely new and at first puzzling vision of what constitutes a fishing boat and a fisherman’s body, but it is one which, in effect, is more realistic than any obtained by fixing the one-eyed, brainless subject […].”[18]

Pierre Huyghe. Nymphéas Transplant (14–18). 2014. Mixed-media installation, live pond ecosystem, light box, switchable glass, concrete, 189 × 143.5 × 128.7 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, London. Supported by Hauser & Wirth. © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2016.

Another central work in the exhibition, Huyghe’s Nymphea Transplant (14-18), 2015, introduces the complexity of interagentivity and co-existence which can help to renew our concept of nature. An aquarium tank with a light box suspended over it sits on a concrete base. It shows entities coexisting in the first layer of the hydrosphere and in the layers of soil, flora and fauna: this aquarium is based on the water lily pond ecosystems of Claude Monet’s gardens in Giverny, composed of plants, fish, amphibians, crustaceans and insects found in the subsurface of the pond. The “smart” glass panels of the aquarium blink from translucent to transparent in an unintentional way. A lighting system is based on French weather archives from the Giverny region: light over the course of four years encompassing World War I (from 1914 to 1918) has been accelerated to match the duration of a “normal” exhibition day. As a result, this combination provides a unique view for each visitor, questioning the very concept of nature – “natural” light, “natural” entities – as something that can be managed though never totally “controlled”[19].

Although placed in the fourth section dedicated to “disputed territories” (see below), Pierre Huyghe’s proposal, which can be discussed in term of sculpture, painting and environment, works also quite well at the intersection of the procedures of the exhibition. This is due to its explicit reference to modernity in painting (visibility, bidimensionality) through its reference to Monet, and the shift from a face-to-face view of an “immersive” painting (the panoramic “Water Lilies” installation or “environment” which can be seen at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris) to the reality of a three-dimensional living ecosystem[20]. Challenging the very idea of control – even the greenish-yellow colour is the result of the interactions that abound in this ecosystem and is not decided by the artist – Huyghe’s discrete intervention nevertheless consists of carefully setting up an ecosystem:

“You frame a rule, set a condition, but you cannot define how a given entity will interact with another. I can never fully determine what animals will do… What I show is a set of elements and the way they collide, confront and agree with each other. In a certain way, I construct a play. I don’t want to exhibit something to someone anymore. I want to do the reverse: I want to exhibit someone to something.”[21]

This can help us to renew not only our concept of nature but also the connected concept of experience. In his text “L’invention du pluralisme”[22], Didier Debaise adopts Dewey’s open and non-determinist definition of experience – the result of the interaction of the live creature and its environment (Art as Experience) – and proposes “panexperientalism” to describe the transformation of this concept by pragmatist philosophers from its modern meaning: “In place of a material nature in which each part is emptied of its aesthetic, expressive and axiological qualities, and which humans experience by projecting onto it their own values, a conception of nature consisting of myriad vital interactions, each a ‘centre of of experience’ in itself, is substituted.” More precisely:

“[N]ature is no longer, as in the classic conception, a homogenous spatial system that can be divided into a plurality of domains – physical or biological – that ready-made beings come to inhabit. It is the result or the effect of a multiplicity of geneses: new existences continually arise, in addition to old ones, to make up, via the combination of their reciprocal relations, a common nature.”[23]

Debaise finds in James the origin of this conception. For James, the nature is a universe composed “of personal lives (which may be of any grade of complication, and superhuman or infrahuman as well as human), variously cognitive of each other […], genuinely evolving and changing by effort and trial, and by their interaction and cumulative achievements making up the world”[24]. As a result, we have to move from indifference to Nature to “due attention” (Whitehead), which takes into account the specificity of any situation.

4. Sharing agencies and responsibilities

At the end of his article “Experimental Music” (1957), which you can be read in the documentary station for Procedure C, “Sharing Responsibilities: Farewell to the Sublime”, John Cage focusses on our interaction with our environment (i.e experience in Dewey’s term) and coins the expression “response ability”[25]. Thus, he links this notion to sensitivity (ability to answer to any kind of entity) rather than accountability (which relates only to humans):

“Hearing sounds which are just sound immediately sets the theorizing mind to theorizing, and the emotions of human beings are continually aroused by encounters with nature. Does not a mountain unintentionally evoke in us a sense of wonder? Otters along a stream a sense of mirth? Night in the woods a sense of fear? […] Does not the death of someone we love bring sorrow? And is there a greater hero than the least plant that grows? These responses to nature are mine and will not necessarily correspond with another’s. Emotion takes place in the person who has it. And sounds, when allowed to be themselves, do not require that those who hear them do so unfeelingly. The opposite is what is meant by response ability.”[26]

Cage invites us to not be indifferent to or unmoved by our environment but rather to ‘pay attention’ to what surrounds us, given that we are no longer outside the world but within it (Procedure B).

In this section of the exhibition, works by Fabien Giraud, Simon Starling, and also by Thomas Thwaites and Unknown Field division later on in Procedure F, challenge the very notion of distance, and help us to reconsider the concept of responsibility: together they point out that, in the age of the anthropocene, we cannot remain distant and indifferent to what was previously called “nature”.

Giraud’s photograph Tout monument est une quarantaine (Minamisōma – Fukushima District – Japan), 2012–14, depicts a clod of soil in the forest of Fukushima. The paper onto which the picture was printed was itself taken from the background environment shown in the photograph and is therefore radioactive. Not only does this work “illustrate a toxic entanglement caused by a tsunami, a nuclear explosion, and an irreversibly-contaminated area made unstable by both natural disaster and human activity alike” (as we wrote in the field book), it also directly challenges two important characteristics of modernity, questioning both the visibility of the catastrophe and our so-called distance from it (the basis of Kant’s definition of the sublime[27]).

Fabien Giraud. Tout monument est une quarantaine (Minamisōma – Fukushima District – Japan). 2012–14. Photograph printed on photographic background used for the shoot, anti-radiation glass sheet with plumb, 15 × 20 cm.

Simon Starling. One Ton II. 2005. 5 handmade platinum/ palladium prints, 86 × 66 cm. Rennie Collection, Vancouver, Canada.

Simon Starling’s One Ton II (2005) is a series of five black-and-white photographs, which are handmade platinum/palladium prints of the Anglo-American Platinum Corporation mine in Mokopane, South Africa. They are produced using exactly the amount of platinum-group metal salts derived from one ton of ore[28]. In doing so, the artist maintains the traces of the generally hidden material provenance. The artist presents this series as a “closed system,” wherein the surfaces of the prints directly “mimic the surface of the brutally grandiose engineering project that facilitated their production”. Self-referentiality is generally associated with the modern idea of the autonomy of a work of art, but Starling strikingly reverts and re-materializes the “medium specificity” also closely associated with modernism. Here the task seems to be a geo-tracing activity: a search not only for the formal characteristics specific to a given medium but for what a work is composed of, and where this material comes from – relocalizing it. Furthermore, the “system” is not entirely closed because of the triangular relation with the observer, placing her/him in a situation that challenges attitudes of critical distance, transformed here into a critical proximity[29]. Similarly, the design research studio Unknown Field Division’s Rare Earthenware (2015) retraces the trajectory of the rare earth materials necessary to build today’s communication technologies[30]. The speculative designer, Thomas Thwaites, attempted to build a toaster from scratch (The Toaster Project, 2011), using only material found close by, thus asking the underlying question: what is our response ability?

Unknown Fields Division. Rare Earthenware. 2015. Mixed-media installation, ceramic, 1-channel HD video, color, sound, 7 min. 3 vases (black stoneware and radioactive tailings). Film and photography in collaboration with Toby Smith, ceramic work in collaboration with the London Sculpture Workshop, animation assistance by Christina Varvia, coproduced by the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Architectural Association, and ZKM | Karlsruhe.

- Thomas Thwaites. The Toaster Project. 2011. Installation, iron, copper, nickel, mica, plastic, and found objects, dimensions variable.

- 5. Towards a Politics of the soil: Critical Zones, Gaïa & Territories

These works enter into a dialogue with an obvious geo-political inflexion in Latour’s recent work[31]. As he wrote, the “interest in the ground and geoscience comes from the common prefix “geo” that geography, geophysics and many other associated disciplines share with geopolitics.“[32] In this article, Latour articulates the concept of critical zones through the figure of Gaia and his specific definition of politics, “defined here as the ‘progressive composition of the common world’ ”:

“I take “critical zone” to mean a spot on the envelope of the biosphere (Gaia’s skin in Lovelock’s parlance) which extends vertically from the top of the lower atmosphere down to the so-called sterile rocks and horizontally wherever it is possible to obtain reliable data on the various fluxes of ingredients flowing through the chosen site (which in practice generally means water catchments). “Ingredients” here does not mean only chemicals or physical elements since “EU legislation”, “agricultural practices” or “land tenure” might be part of the data to recover from the study just as well as the amount of nitrates. By its leopard skin nature, the very way in which critical zone specialists try to compare and assemble their findings offers a much more realistic picture of a political process (in the sense just defined) than the idea of “planetary politics”. While it is impossible for people to grasp what it is to take up responsibility for the stewardship of the whole planet, it is much easier to see where one stands in relation to a critical zone of variable dimensions.”[33]

Critical zone Observatory South Sierra directed by professor Roger Bales.

The parallel with the necessity to renew the concept of nature is here obvious:

“Such a definition implies that there is no world that is already common to begin with (contrary to the older argument that since Nature is the same for all, agreement would come automatically by sharing Nature’s laws); it also implies that this commonality has to be composed (that is, pieced together, element after element, through many travails and conflicts); it also means that it is “progressive” in the sense that it gives a direction forward, it is open to debate and it is slow because it depends on bringing many incommensurable interests, values and entities together in a common modus vivendi. Defined in that sense the word “politics” is not limited to humans but includes all the elements or entities deemed part of the composition of the common world. This is what allows one to speak, for instance, of the “politics of the soil” because the world to consider is made just as much out of humus as it is made out of EU subsidies for maize, fermentation in the gut of earthworms, pluviometry or the consumer’s appetite for “bio” food.”[34]

A series of photographs of the Calhoun Critical Zone Observatory, shown at the far right of the documentary section, provides an example of soil destruction in South Carolina, a landscape highly altered and degraded by over a century of farming and cotton cultivation[35], which can be compared to David Maisel’s The Lake Project 2. The work is part of a series called Black Maps, which uses photography as a record but also as a metaphor for the alteration of a terrain. This arid and ambiguous photograph documents Owens Lake, which was drained at the beginning of the twentieth century to support the rapid urban expansion of Los Angeles. The draining of the lake exposed vast mineral flatbeds to violent winds, resulting in carcinogenic dust storms (The red colour is caused by a concentration of minerals and bacteria in the thin layer of remaining water). As a result, this area is the largest single source of particulate matter pollution in the United States.

Example of soil destruction in South Carolina. Calhoun Critical Zone Observatory. 2015.

David Maisel. The Lake Project 2. 2001/15. Photograph, printed as archival pigment print, 2015, 122 × 122 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Ivorypress Gallery, Madrid, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York.

We live thus in a “laboratory planet”[36], another name for the “anthropocene”, or the “new climatic regime” in Latour’s vocabulary. Latour links this to Gaia, a term invented by the scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis at the beginning of the 70s. Isabelle Stengers, from whom Latour borrowed the concept, reminds us that this concept was first introduced to describe an “assemblage of relations” – interagentivity[37]– “that scientific disciplines were in the habit of dealing with separately – living things, oceans, the atmosphere, climate, more or less fertile soils”. As a result, it has two consequences, says Stengers: “That on which we depend, and which has so often been defined as the ‘given’, the globally stable context of our histories and our calculations, is the product of a history of co-evolution […]And Gaia, the ‘living planet’ has to be recognized as a ‘being’, and not assimilated into a sum of processes”[38]. Latour also insists that Gaia should not be taken as a totality, as a system nor as an organism[39].

And here again we come back to the question of limits, widely discussed at the moment in geopolitics, and which Latour links to the redefinition of a territory, since we – including the scientists studying the critical zones – realise that we don’t really know that much about it. In a recent talk at the London School of Economics, Latour raised the issue of the representation of overlapping territories that might correspond to a more realist way of understanding to which soil we belong[40]: “If we reconsider the definition of territory as that on which we depend to subsist, what is limited by other territories (not necessarily by contiguous borders), what may be represented, to what we are attached, what we are ready to defend, can we morph traditional base maps to stop denying overlapping territories?”

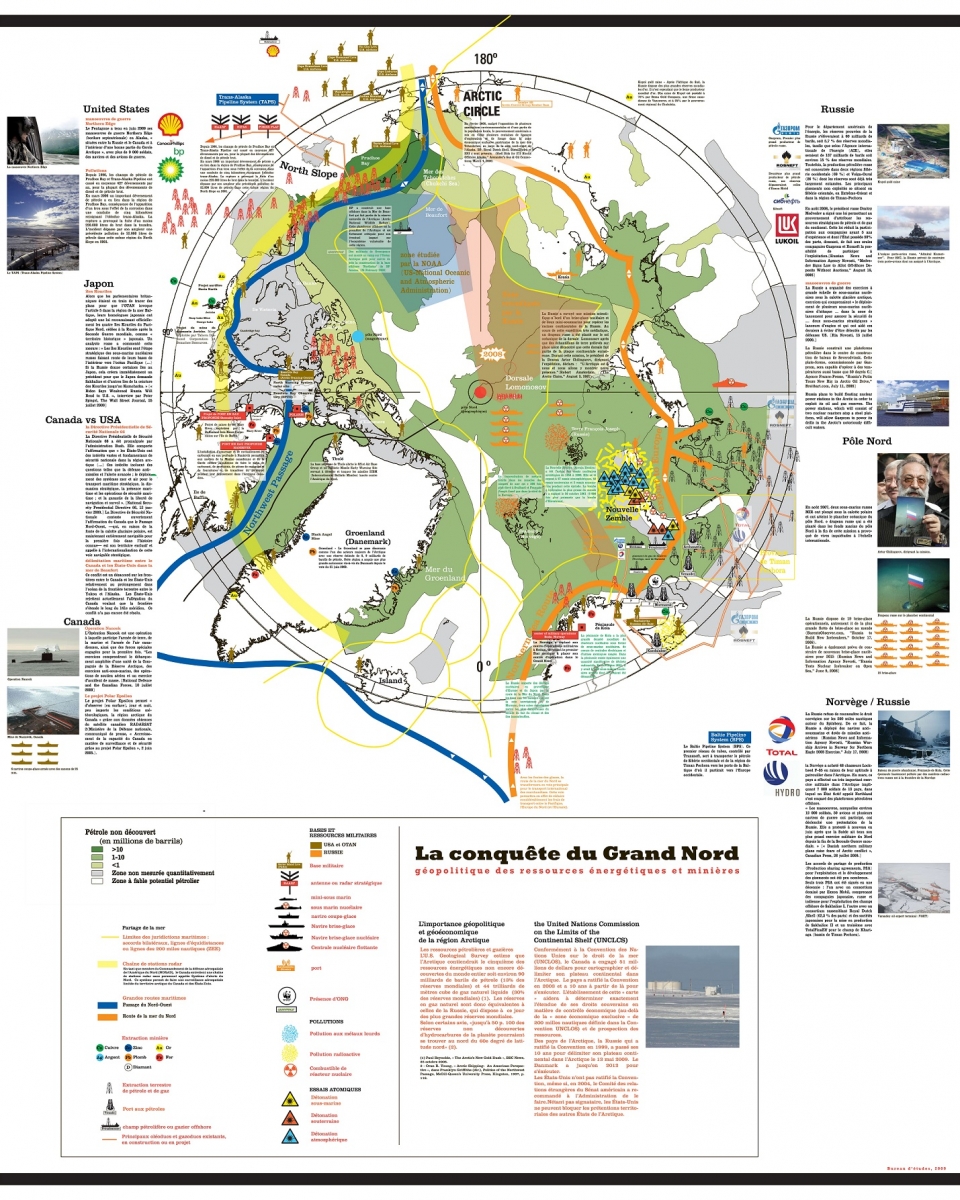

The Bureau d’Études map of the Arctic, which focuses on the three major questions concerning the Arctic (climate change, new waterways and the exploitation of natural resources) and Territorial Agency’s Museum of Oil, showing five territories shaped by oil, at once fragile and dangerous (from the fracking boom in Texas to the militarisation of the supply chain in the Middle East), can be seen as first attempts to draw attention to the current and surreptitious reconfiguration of territories. To counteract this transformation, we would need to transform our economy through political decisions.

Only then can the diplomatic work starts. And this is why we need experiments such as Sylvain Gouraud’s Shaping Sharing Agriculture, which is not only a photography project but also a means of gathering all the actors involved in agriculture to discuss issues relating to the food industry (the basis to a concrete politics of the soil), or Make it Work at Théâtre des Amandiers, Nanterre, 2015, a student simulation of international climate negotiations in May of 2015 aimed at addressing climate change and its related geopolitical issues. The problem is therefore not to only to represent not only non-humans (to give sovereignty and delegation[41]) but also mapping interagentivities that emerge together – all the feedback loops.

Bureau d’Etudes. La conquête du grand Nord. Géopolitique des ressources énergétiques et minières. 2008. Map. 120 × 100 cm.

Territorial Agency (John Palmesino, Ann-Sofi Rönnskog). Museum of Oil. 2016. Mixed-media installation, prints on aluminum panels, aluminum panels on a metallic framework, videos. Reset Modernity! ZKM, Karsruhe, Germany, 2016. Photo: Tanja Meißner.

Sylvain Gouraud. Shaping Sharing Agriculture. 2014–16. Mixed-media installation, large format photographic slides, projection box, tripod, screen, speakers, dimensions variable. Coproduction with La Société pour la diffusion de l’utile ignorance, Le Shadok, and ZKM | Karlsruhe. Reset Modernity! ZKM, Karsruhe, Germany, 2016. Photo: Jonas Zilius.

Make it Work at Théâtre des Amandiers, Nanterre, 2015.

6. How to land without crashing?

Hybridity should be considered as a provisional, and not a definitive concept, for detecting symptoms or anomalies in the modernist way of thinking. Stating and repeating that everything is a hybrid could paradoxically lead to a strengthening of the concepts which are embedded in modernist dichotomies (nature/culture, global/local, object/subject, mind/body, etc., but also human/non-human…); these dichotomies should not be overtaken but simply ignored.

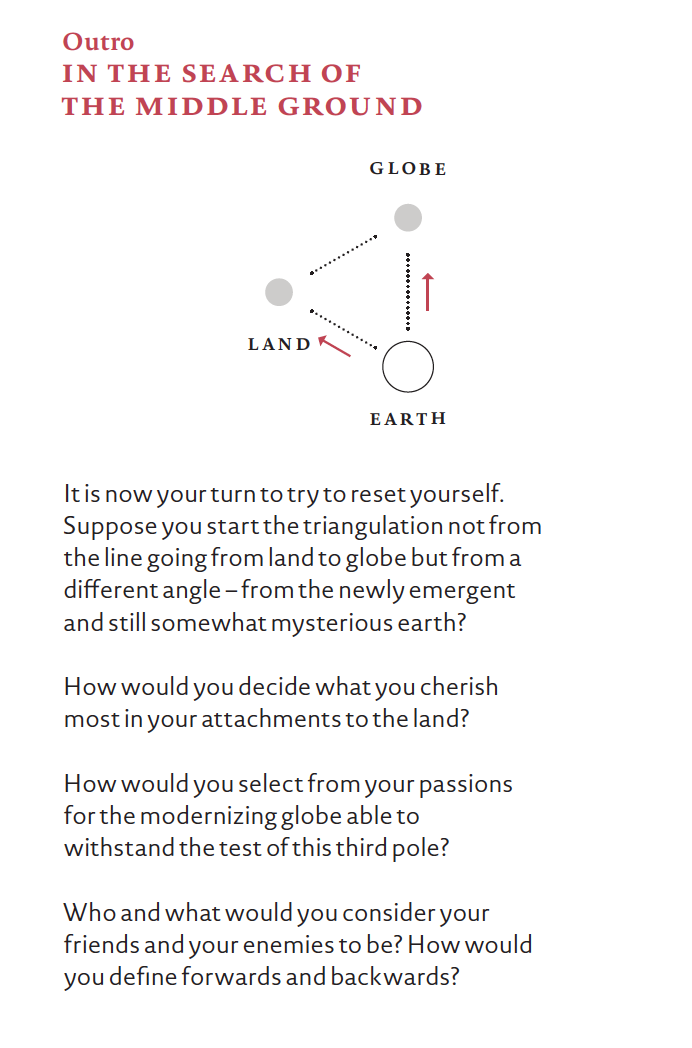

To better know how to land without crashing, we need instead to renew our abstractions and reinstitute nature, politics, economy or religion. Latour’s triangle representing three attractors – Globe/Land/Earth – shows how difficult it is to avoid such dichotomies but can be considered as an interesting and promising attempt to escape from this specific and exclusive modern way of thinking – aimed not only to better understand our current situation but also to act accordingly.

Page of the Field book Reset Modernity!

This article first appeared on Artnews.lt magazine’s issue “Hybrid summers” curated by Vytautas Michelkevičius among the texts by Jussi Parikka, Tautvydas Bajarkevičius and others.

[1] This text is a version of a presentation on Reset Modernity! given at the Inter-Format Symposium, at the Nida Art Colony, 25th July, 2016. All the works mentioned can be found in the field book. http://modesofexistence.org/field-book/

[2] Bruno Latour. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993.

[3] “This is why the link between philosophy and anthropology should not be defined by some ‘ontological turn’: ontology has been there all along and has been essential to the modernist project.” Bruno Latour. “Another Way to Compose the Common World.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4, no. 1 (June 23, 2014): 302. In philosophy, ontology refers to the study of being, existence and reality. This is what we have been trying to do for five years by means of the project, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. “If we have never been modern, then what has happened to us? What are we to inherit? Who have we been? Who are we going to become? With whom must we be connected? Where do we find ourselves situated from now on?” (Our emphasis.)

[4] See for instance, and as examples of exhibitions directly addressing this issue of the recognition of the non-humans, and challenging human ethnocentrism, the exhibition Animism, Mar 16—May 06, 2012, Berlin, or Être Chose (Being Things), 5 July-1 November 2015, Centre International d’art et du paysage, Vassivière en Limousin, France. One of the most striking is probably Pierre Huyghe’s retrospective, 2014, Los Angeles, Köln, Paris.

[5] Bruno Latour, “Network” in An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. http://modesofexistence.org/aime/voc/507. See also the vocabulary entry “[NET]” : “All things grasped as [NET] beings, appear as a network of associations whose ins and outs we can follow and which lead, step by step, to increasingly heterogeneous elements.”

[6] See Bruno Latour and Christophe Leclercq, eds. Reset Modernity! Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

[7] Bruno Latour, Face à Gaïa : huit conférences sur le nouveau régime climatique. Paris, France: Les empêcheurs de penser en rond : La Découverte, 2015. Philip Conway is right when he writes that “every aspect of Latour’s thought has political ramifications”. But his interest in the Earth, soil or ground is recent and seems to be influenced by Peter Sloterdijk’s theory of space, James Lovelock’s concept of Gaia, and Clive Hamilton’s recent philosophical writings on the ecological crisis. See Conway, Philip. “Back down to Earth: Reassembling Latour’s Anthropocenic Geopolitics.” Global Discourse 6, no. 1–2 (January 2, 2016): 43–71. This doesn’t mean that there are “two” Bruno Latours, as some members of the Breaking Institute argued, ony that there is a geo reorientation in his political thought.

[8] Economics was die to be explored also, but we had no time to work the subject thoroughly.

[9] See Bruno Latour interviewed by Hans Ulrich Obrist for the history of Latour’s other thought exhibitions, Iconoclash (2002) and Making Things Public (2005) and their relation to other exhibitions, such as Les Immatériaux by Jean-François Lyotard: http://modesofexistence.org/what-is-a-gedankenausstellung/

[10] Needless to say that concepts are efficient as Latour showed it in We Have Never Been Modern.

[11] In a recent seminar organized by Christophe Bonneuil at EHESS, Paris (2016), it was proposed that the term “other-than-human” (“autre qu’humain”) be used instead of “non-human”. This new term is probably less negative but still dualist in character. We might also refer here to the subtitle, “We have never been human”, in Donna Haraway’s When Species Meet.

[12] Mylène Ferrand Lointier, “Interview: Bruno Latour on the Show Reset Modernity! At the ZKM.” Seismopolite. Journal of Art and Politics, 2016. http://www.seismopolite.com/interview-bruno-latour-on-the-show-reset-modernity-at-the-zkm.

[13] Latour & Hermant state: “We now know, every panopticon is an oligopticon: it sees little but what it does see it sees well.” Bruno Latour and Emilie Hermant. “Paris: Invisible City.” Translated by Liz Carey-Libbrecht, 2006. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/virtual/EN/index.html.

[14] Bruno Latour. “Armin Linke, or Capturing / Recording the Inside.” In Armin Linke – Inside/outside, 42–44. Arnhem: Roma Publications, 2015. Also reproduced in the Reset Modernity! catalogue.

[15] Didier Debaise, Pablo Jensen, Pierre Montebello, Nicolas Prignot, Isabelle Stengers, and Aline Wiame. “Reinstituting Nature: A Latourian Workshop.” Environmental Humanities 6 (May 1, 2015). https://doaj.org.

[16] “On one side an ‘objective’ nature, blind to our values, indifferent to our project; and on the other a nature which is the very stuff of our dreams, values and projects.”

[17] Cyril Neyrat, “Blood of the Fish, Beauty of the Monster.” Cinema Guild, n.d. http://cinemaguild.com/homevideo/ess_leviathan.htm.

[18] Bruno Latour and Christophe Leclercq, eds. Reset Modernity! Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016.

[19] One might challenge the artist’s idea of a “natural” depiction by Monet, given the knowledge that “the aquatic plants inside the aquarium were procured from the gardens of Latour-Marliac from where Claude Monet originally bought his water lilies.” To a certain extent, everything is composed…

[20] The shift from the vertical to the horizontal plane in painting is one of the characteristics that lead the art critic Leo Steinberg to use the term “postmodern” in Robert Rauschenberg’s painting. Huyghe’s work has a lot in common with Rauschenberg’s work. See Rauschenberg’s text “Random Order” published in Location 1 (1962) and his work Oracle (1962-1965), which also challenges the art categories of sculpture/painting/environment and how the visitor relates to them.

[21] Pierre Huyghe in The Art Newspaper, September 23, 2013. In French, “exhibit someone to something” (“exposer quelqu’un à quelque chose”) and also (primarily) to expose one to risks.

[22] Didier Debaise, “L’invention du pluralisme“, 2016, not translated.

[23] “The universe consists of ‘centres of experience’; subjects, both human and non-human, physical, biological, psychological, in constant variation, and which, by means of their interactions, form the various orders of nature.” Translated by Owen Martell.

[24] William James, Collected Essays and Reviews, New York, Longmans, Green and Co., 1920, p. 443-444. Quoted in Debaise, “L’invention du pluralisme”. This definition lead, interestingly, to the question: what is a persona? According to Anne-Christine Taylor, curator of the exhibition Persona. Strangely human, Musée du Quai Branly, a persona is characterized by a subject (intention, etc.) and a shape.

[25] The notion of responsibility is at the heart of Experiments in Art and Technology’s statements. E.A.T. members had already noted the consequences of human action on the environment and tried to elaborate a theory of action (collaboration between artist and engineer) to deal with this new situation. They renewed the concept of environment understood not as a synonym of “green/wild/pure nature” but as a hybrid of what the Moderns think of as nature and culture.

[26] John Cage, “Experimental Music”, p. 10.

[27] In his definition of the sublime, Kant insists on the fact that the feeling for the sublime can only happen if the subject is contemplating the spectacle of Nature from a safe position.

[28] Since the metal is dispersed across huge amounts of ore, one ton of ore was necessary to make the five prints.

[29] Bruno Latour, “Critical Distance or Critical Proximity ? A Dialogue in Honor of Donna Haraway,” 2005. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/P-113-HARAWAY.pdf.

[30] As we wrote in the field book, “They used mud from a barely-liquid, radioactive lake in Inner Mongolia to craft a set of ceramic vessels that resemble traditional Ming vases. Each one of them is made from the same amount of toxic waste created in the production of a smartphone, a featherweight laptop, and the cell of an electric car battery.”

[31] Bruno Latour, Face à Gaïa : huit conférences sur le nouveau régime climatique. Paris, France: Les empêcheurs de penser en rond : La Découverte, 2015 (forthcoming translation, Polity, early 2017).

[32] Bruno Latour, “Some Advantages of the Notion of ‘Critical Zone’ for Geopolitics,” 2014. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/P-169-GAILLARDET-pdf.pdf.

[33] Ibid. p. 2.

[34] Ibid. p. 1-2.

[35] “The Calhoun CZO integrates human and natural forcings of Earth’s Critical Zones and the sciences of water, mineral, and organic matter cycles. Calhoun CZO scientists seek to understand how Earth’s Critical Zones respond to and recover from severe erosion and land degradation. […] Researchers will use historic and contemporary data of vegetation, soil, catchments, and sensor networks to help hindcast and forecast Critical Zone dynamics and evolution across temporal and spatial scales.” http://criticalzone.org/calhoun/about/

[36] See Ewen Chardronnet and Bureau d’Etudes’ project. http://laboratoryplanet.org/en/.

[37] Talking about Lovelock, Latour wrote: “But he has detected that his geologist, climatologist and biochemist colleagues have thwarted for no good reason the description of what they had in full view, namely that at every point where outside causality was supposed to act alone, lots of other agencies were acting just as well.” And, further: “Lovelock frees their science by […] distributing agencies at every point along the causal chains.” p. 21

[38] Isabelle Stengers wrote: “What I am naming Gaia was in effect baptized thus by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis at the start of the 1970s. They drew their lessons from research that contributed to bringing to light the dense set of relations that scientific disciplines were in the habit of dealing with separately – living things, oceans, the atmosphere, climate, more or less fertile soils. To give a name – Gaia – to this assemblage of relations was to insist on two consequences of what could be learned from this new perspective. That on which we depend, and which has so often been defined as the “given,” the globally stable context of our histories and our calculations, is the product of a history of co-evolution, the first artisans and real, continuing authors of which were the innumerable populations of microorganisms. And Gaia, the “living planet” has to be recognized as a “being,” and not assimilated into a sum of processes, in the same sense that we recognize that a rat, for example, is a being: it is not just endowed with a history but with its own regime of activity and sensitivity, resulting from the manner in which the processes that constitute it are coupled with one another in multiple and entangled manners, the variation of one having multiple repercussions that affect the others. To question Gaia then is to question something that holds together in its own particular manner, and the questions that are addressed to any of its constituent processes can bring into play a sometimes unexpected response involving them all.” Isabelle Stengers. In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism. Open Humanities Press, 2015. http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/in-catastrophic-times/ p. 44-45.

[39] Pending translation of Latour’s latest book Face à Gaia (La Découverte, 2015) one can read Bruno Latour, “How to Make Sure Gaia Is Not a God of Totality?” with particular reference to Toby Tyrrell’s book On Gaia,” 2014. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/fr/node/587. It is particularly important here to get rid of the cybernetic metaphor of a closed system, and to avoid any reference to Buckminster Fuller’s own metaphor: “Gaia, for Lovelock, could be called No Machine and that’s why, of all the metaphors he criticizes, none is damned more relentlessly than Space-Ship Earth.” p. 22

[40] http://modesofexistence.org/how-to-visualize-overlapping-territories-3/. Bruno Latour, Millenium LSE London, October 2015.

[41] Bruno Latour, “On Sensitivity Arts, Science and Politics in the New Climatic Regime”. PSi #22, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTzhTlrNBfw