Few weeks ago, the prime ministers of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia agreed to open their borders to each other from 15 May, following the successful management containing the coronavirus.[1] Museums and art spaces have also been reopening in all three countries, adopting the necessary sanitation procedures and visitor numbers speedily, though not without anxiety and stress for museum workers.

The beginning of the pandemic now seems far away in the past, when my head was constantly buzzing with information from the latest articles shared by friends from all over the world, critical essays analysing the reasons for and the possible aftermath of Covid-19, and practical solutions that artists and institutions put in place to survive and overcome the crisis. I was enthusiastic and eager to share and think together about how we could help our local art community and wider society in Latvia, steering the country in the right direction. The rapid adaptation to the new conditions working from home, with art institutions putting their collections and exhibition videos online, and rescheduling planned events through Zoom, is stabilising, and the need for a more sustainable approach is arising.

As the writer and social activist Naomi Klein suggested in a recent video, ‘In times of crisis, seemingly impossible ideas suddenly become possible. But whose ideas? Sensible, fair ones, designed to keep as many people as possible safe, secure, and healthy? Or predatory ideas, designed to further enrich the already unimaginably wealthy while leaving the most vulnerable further exposed?’[2] With these sensible ideas as a guiding principle, I would like to highlight some structural proposals and gestures of solidarity I have observed during the crisis on the art scene in the Baltic region.

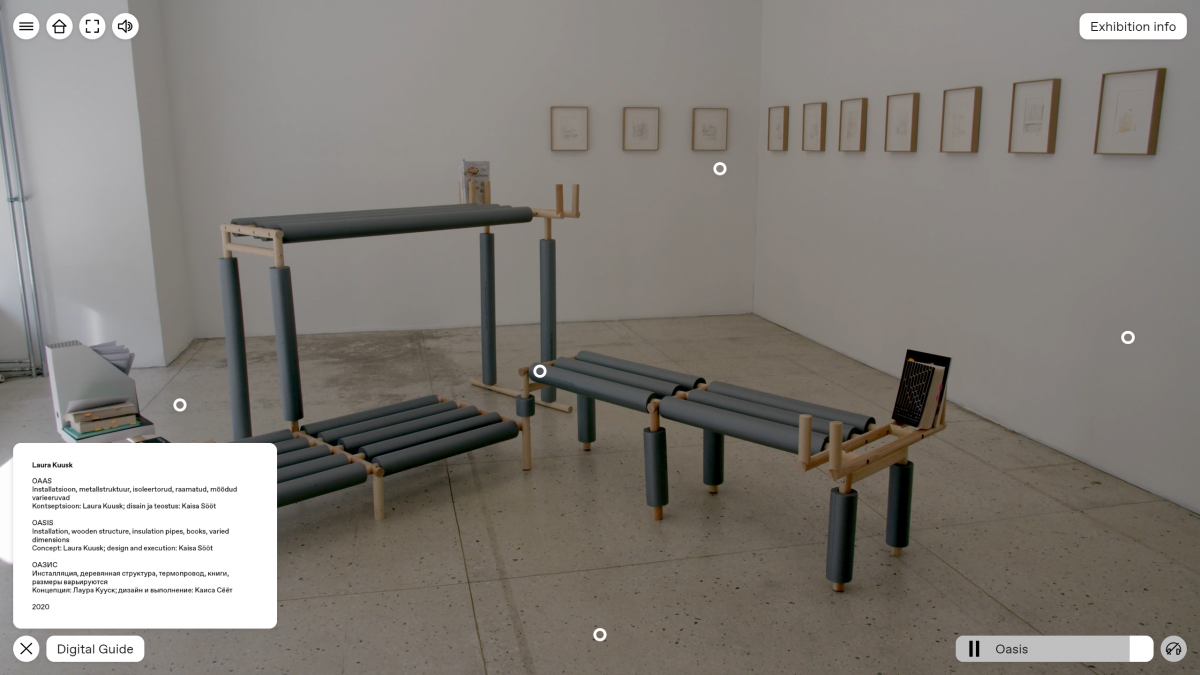

A long-planned initiative, but one coming right at the beginning of the pandemic, was the virtual exhibition space of Tallinn Art Hall. Well programmed and carefully thought out, easy to navigate in three dimensions, and accompanied by explanations in Estonian, English, Russian and sign language, it revealed a sincere engagement with the question of audience accessibility, as opposed to a quick reaction in the heat of the crisis and museum closures. On the platform opening webinar, the director of the art space stressed that the virtual tour broadens accessibility to their physical exhibitions for the differently abled and people who are abroad. Last December, Tallinn Art Hall held the exhibition and programme ‘Disarming Language: Disability, Communication, Rupture’, curated by Christine Sun Kim and Niels Van Tomme, highlighting their commitment to the question of disability. It was built on the ‘Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ (2006), while being critical of its use of the righteous language of rights, and aiming to open up to other, often under-represented or misunderstood, challenging concepts of the language surrounding disability and disabled people. The exhibition not only approached the subject conceptually, but questioned and changed spatial conventions of exhibitions, from the seemingly small and banal questions of the height at which works and captions are hung, to broader questions of how comfortable our bodies feel and move within the space.

Another example of an art institution questioning access, which coincides with the Covid-19 crisis and has moved online, is the Vilnius-based Rupert programme on care and interdependence, based on disability studies and activism. As an antidote to individualism and competition, the programme’s overarching goal is to show how we are all connected socially and environmentally, through personal and institutional ties. This interconnectedness and network of co-dependencies enforced by globalisation in recent decades have been badly shaken by the new Coronavirus, exposing its fragility and weak points. A real gesture of care and responsibility in this situation has been Rupert’s opening its residency to local residents, not only because international travel has ceased in most of the world, but also knowing that a lot of local artists may have a real need to find a place and time to work, lacking the resources to rent a studio during the pandemic.

Another example of an art institution questioning access, which coincides with the Covid-19 crisis and has moved online, is the Vilnius-based Rupert programme on care and interdependence, based on disability studies and activism. As an antidote to individualism and competition, the programme’s overarching goal is to show how we are all connected socially and environmentally, through personal and institutional ties. This interconnectedness and network of co-dependencies enforced by globalisation in recent decades have been badly shaken by the new Coronavirus, exposing its fragility and weak points. A real gesture of care and responsibility in this situation has been Rupert’s opening its residency to local residents, not only because international travel has ceased in most of the world, but also knowing that a lot of local artists may have a real need to find a place and time to work, lacking the resources to rent a studio during the pandemic.

At the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art where I work, we observed how viable solutions were realised through online Hackatons, such as a platform to help with shopping or walking the dog for people who are self-isolating, or simple solutions on how to produce the face shields for emergency ventilators. We wondered whether the method of a Hackaton could be used specifically for the cultural sphere, which is also caught up in a crisis, with most events being cancelled and social distancing rules in place for the foreseeable future, and teamed up with the Northern Dimension Partnership on Culture, which had a similar idea. The idea of a Hackaton comes from the technology industry, and is an event, typically lasting several days, in which many people meet to engage in collaborative computer programming. It responds to a problem, and works on the solution with an interdisciplinary team, aiming to create something innovative and experimental that would not be possible otherwise. Its name, a combination of hack and marathon, connects exploratory programming with long-distance running. With its 48 hours, it is more like a sprint than a marathon, though.

While there are plenty of ideas in the field of art that we should not even think of developing through this method, it can work for certain solutions. Few of the ideas focussed on apps for museums offering online ticketing services and regulating the circulation of visitors, which will be important as we navigate the pandemic. However, an electronic system that connects museums and their ticketing and visitor services is nothing new in itself, but something that should have been implemented a long time ago. Apparently, a crisis situation was crucial to gain the necessary financial and infrastructural support for it to be implemented.

Another sign of a healthy and forward-looking country is that, along with universally accessible health care and education systems, there is support for artists and the cultural sector from the government. While none of the Baltic countries can or should naively compare themselves to Germany, whose rolled-out support for freelance cultural workers was praised in the media, and confirmed as actually working by friends, all the Baltic countries also had schemes to help artists, compared to many countries which did not. The crisis coincided with the first year that Latvia launched the first long-term ‘salaries’ paid to artists, the system having already long been in place for creatives in Lithuania and Estonia. I felt a similar delay in more art workers becoming eligible for the benefits in Latvia, too, while the neighbours were already receiving them. As the gallery owner Olga Temnikova notes in a recent interview, artists in Estonia are generally well supported, even if the art market turns out to be affected by the crisis.[3]

Since I have a unique chance to put a mirror up to cultural policy processes in Latvia, to which I am a daily witness, I have to mention that the biggest commitment to and solidarity with artists and art workers in Latvia comes from the Association of Contemporary NGOs. Members of this association include the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, the kim? Centre for Contemporary Art, the New Theatre Institute, and many others. Financially precarious, since they do not receive planned state support, they regularly apply for grants. However, their demands for the cultural sector and advocacy at the government level prove to be most inclusive for artists. At the same time, for artists’ demands for fair pay to be heard and followed by institutions they could themselves unite and influence the situation. If derelict Soviet relics like the Artists’ Union has long lost its role in representing artists, one can look for examples elsewhere, like W.A.G.E. in the US of Platform BK in the Netherlands, which advocates for better art policy representing artists, curators, producers and other independent art workers.

Another example of structural help I would like to mention, however, comes from outside the cultural sphere. The Make Room association, which has been working with issues of inclusion, often serving as a contact point for foreign, mostly Indian students, in Riga, received the alarming information while the crisis developed that they were often the first ones to lose their jobs, and could now receive wire transfers from their parents in India in time to pay for their daily expenses. A reaction to the crisis came from the Make Room association, to see through the process of how they, as legal residents of Latvia, are eligible to receive crisis support. It is something they would never have known about, as the country is still unready to explain and apply to its many foreign residents their rights to support. It is an example of care and solidarity, as well as administrative knowledge that is shared with people who need it but previously had no access to it.

Kai Art Center

A similar case of support for a particular need in the art world is the Contemporary Art Centre Kai, which offered administrative help at the height of the pandemic to artists applying to the state for relief funding. In fact, offering administrative and legal help for artists and organisatsions is something the Estonian Contemporary Art Center (which shares part of the team with Kai) has been doing for a while, but with COVID19 they reactivated and adapted their resource for the crisis management, also, in collaboration with the CCA Estonia, they gathered information on relief funds and possibilities and conducted a survey on how artists and institutions are affected and surviving the crisis. While both ECADC and the CCA Estonia, in very different ways, have been focussing on international partnerships and exposure of Estonian artists, Kai is a recently opened art centre with a remarkable physical exhibition venue, which raised a question – what else can be the function of a representation institution once it is closed? What other functions in serving its community could it take on, instead of simply putting its programmes online? In addition to the inspiring examples of Make Room and Kai in their activism and the social dimension of their adaptation to the needs of their communities, I would like to stress the exhaustive work behind the scenes of memory institutions, as well as representative ones, working with collections, archives and programmes, to successfully reopen once planned. It takes time, as does research, which all curators (and artists) usually lack. Perhaps this could be the time to see to that, as well as simply observing and taking in the changes, to be prepared and not to slip into oversimplification when interpreting the situation in their next programmes and works.

While I fully support live encounters with artworks, and physical exhibitions with their spatial choreographies of human and non-human material agencies mixing and merging, when I think what we should take with us to the post-pandemic era, I think about the meaningful online reading group sessions I have had with friends all over the world. One of them, the LCCA Evening School, which has been physically part of our programme for several years, based on discussing writings about urgent issues of the times, has gained a new audience in the online environment, as people from abroad have been able to join, as well as those at home with children, without having to spend time commuting to our office.

Over-excitement aside, an important point put forward by the director of the Latvian National Library in one of the cultural policy meetings is that while we are adapting our work more and more to the digital environment, and even responding to new audiences and their needs in it, we should not forget the ‘digitally excluded’, or people who do not have access to digital devices. Often a generational divide, it is an important issue to address, and see where libraries and museums, physically, could serve as meeting points between the generations and people with different accessibilities.

Lucavsala allotment gardens. Photo: Inga Lāce.

While a good half of the artists in the Baltic countries seem to be enjoying the slower pace of life and work, documenting their cities and the changes, gardening, or moving to the countryside, sometimes with the financial constraints already present, or looming in the near future, curators are voicing possible future models for state support for the arts. Public commissions for artists and research are mentioned in almost all plans for the sustainable restitution of the art world. They have also finally reached the Latvian Ministry of Culture as a programme. A practical example merging the need to socially distance with art in public is the solo show by the Lithuanian artist Kipras Dubauskas, which was planned for the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, but will be a major outside installation and series of events this June. In this case, of course, it suits the artist’s practice, since it is connected with exploring suburbs, city tunnels and islands, as viable alternatives to centres.

What is public and how it should be treated is an important issue that has been raised during the pandemic. Modelling green post-pandemic scenarios from an American perspective, the city planners and architects Billy Fleming and Alexandra Lillehei note: ‘Suddenly, our parks, trails, wide sidewalks, rooftops, and balconies are bustling — full of people seeking a respite from isolation in the green and civic infrastructure that binds our communities together. Several national parks grew so overcrowded that, as social distancing became impossible, they had to close. An axiom among disaster planners is that events like the pandemic do not cause inequality, they merely reveal it. While that’s certainly true of COVID-19, it is also showing just how vital our public spaces and infrastructures are to everyday life.’[4] Those spaces reimagined by planners, communities and artists together would also be my ideal post-pandemic scenario for the Baltic States. After all, those green areas and places to ‘avoid each other’ publicly, like parks, allotment gardens, coastal forests and sparse regional towns, have been one of the reasons for the rather quick containment of the coronavirus, alongside efficient and early government restrictions.

Observing the development of this crisis, I cannot help thinking about my generation, which has come to expect it as young adults. While the hectic process of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the restoration of independence in the Baltic countries was taking place in the 1990s, we were just children, or students, or just out of university during the economic crisis of 2008, this time the countries themselves, as well as our generation, are experienced enough to take responsibility and initiate change. I see my artist and curator colleagues in the Baltic countries who work on the art scene addressing difficult questions of nationalism, democracy in times of heightened surveillance, and border closures, aiming for more open, diverse and inclusive societies. We can imagine anew the failed projects of previous generations, such as the never-built Contemporary Art Museum in Latvia, already with a deep knowledge of pandemics and environmental and social sustainability; or think of other alternatives that we see as necessary for the art scene. And we should be careful to safeguard, and if necessary carve out, that space for artists to create and experiment in the period of the crisis and beyond.

Let us turn back to the question of borders that I mentioned at the very beginning. The regional opening up of the Baltic countries is a positive sign that we may soon travel and exchange again. However, it will take time for carefree mobility to return. Thus it is a good moment to rethink our relationships with our closest surroundings. Any locality, including the Baltics, has a lot of diversity within it, ethnically, socially, and instead focussing on understanding that and thinking how to work with that is exactly what pandemics is giving us time and urging us to do.

While I agree that more sustainable and more ecologically aware travel should become a habit, I would like to stress that for small and geographically peripheral countries, the exchanges made possible by international travel have always been a significant and enriching part of our local ecosystems that challenge our provincial and often nationalistic cultural scenes. A fellow curator that I met in the gardens of the Villa Vassilieff a couple of years ago describes my concerns thoughtfully in one of her ‘Letters against Separation’ during the pandemic: ‘My rich experience of being able to pass through the sliding door of the global art world provides me with a sense of relational criticality and self-reflexivity. I’m more aware than before of the privilege of being minorities, of being able to enjoy the celebrated moments of transnational friendship and loyalty, the emancipatory powers of after-midnight encounters in strange new places, the warm-hearted chats in the corner of an after party, the genuine face-to-face conversation with someone who stays past the Q&A section of a talk … We embark on journeys to refresh our personal identity and ideological backdrop, to get lost on the ground, to be confronted by others and relate to one another in an imagined community […] Am I ready to tell our new curatorial intern that such prospects won’t be promised for their generation that emerges after the end of the current crisis?’[5]

In a Zoom conversation with a friend in Paris a few days ago, we discussed how there could definitely be a middle ground. A sustainable art world where a certain degree of travelling is permissible, and instead of turning towards local micro-initiatives to counter the culture of mega-events and biennials that has come as a consequence of globalisation, we could work for the medium, the middle. This is not a radical solution, but an alternative to support and work for.

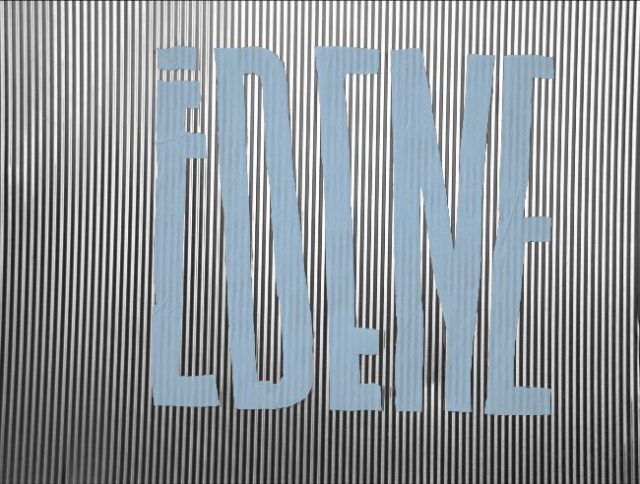

Endless Story by Mihkel Ilus and Paul Kuimet at Tallinn Art Hall, curated by Siim Preiman

The Best You Can Ever Be by Ede Raadik at Tallinn City Gallery, curated by Corina Apostol

[1] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-baltic/baltic-states-to-create-travel-bubble-as-pandemic-curbs-eased-idUSKBN22I13A

[2] https://www.yesmagazine.org/video/coronavirus-naomi-klein/

[3] https://arterritory.com/en/visual_arts/topical_qa/24819-we_just_have_to_stop_worrying_and_do_our_best?fbclid=IwAR0HSuUC0Y8nHcusfwuuphfgLAKPnx2TwVwebfWqaVbbnYfh-Pz9D1lCZgQ

[4] BILLY FLEMING, ALEXANDRA LILLEHEI, To Rebuild Our Towns and Cities, We Need to Design a Green Stimulus, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/04/green-stimulus-new-deal-infrastructure-buildout-coronavirus?fbclid=IwAR0On8fBHCjlngpagMmIT5ZQ10AAFU2oZqnYyVnv1Zo2D__LH5R8ftGj5wc

[5] Nikita, https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/letter-against-separation-nikita-yingqian-cai-in-guangzhou/9945