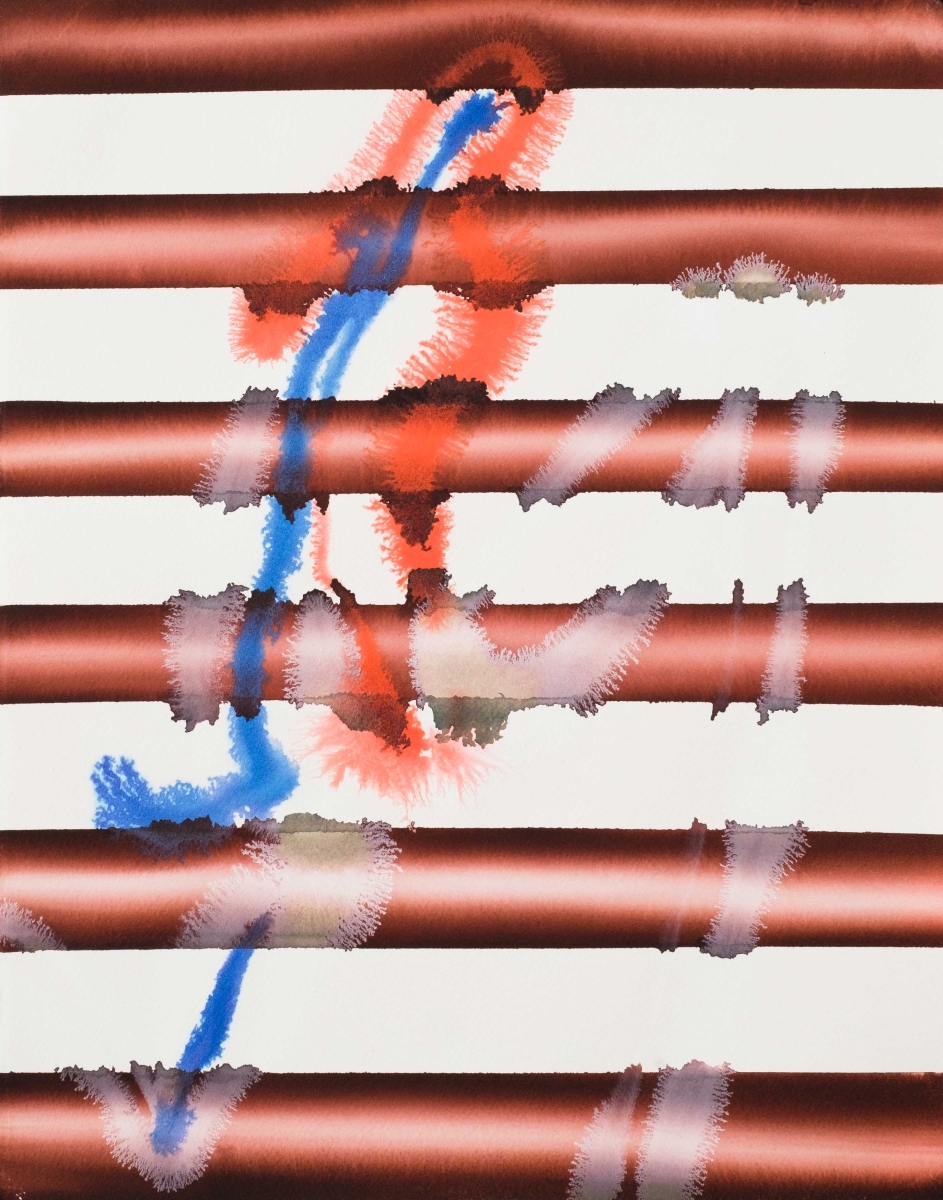

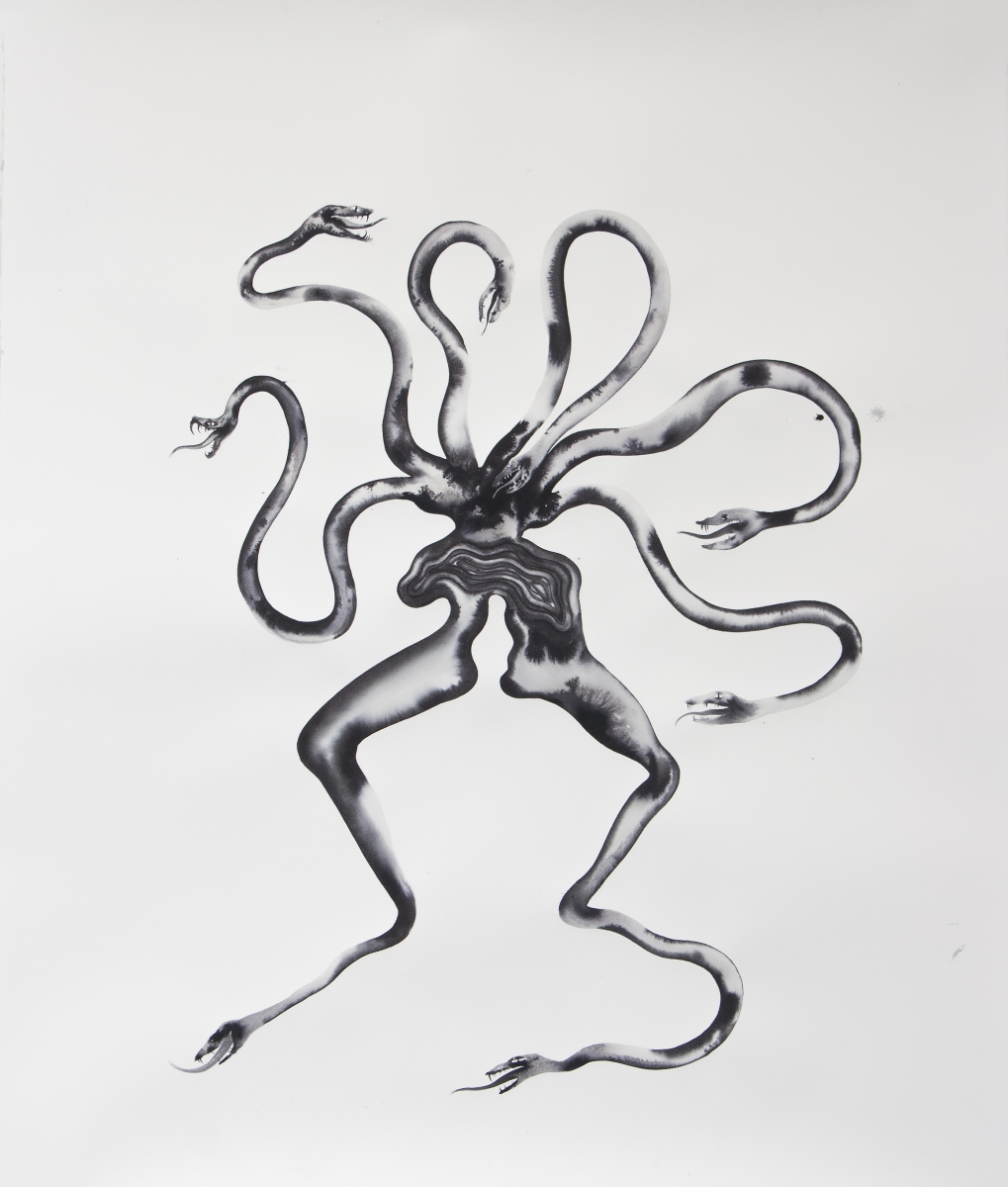

The Latvian artist Sabīne Vernere is known for her expressive Indian ink paintings depicting anthropomorphic, gender-fluid beings. Opting for a limited, often monochromatic palette of colours, she diffuses her images on an abstracted plane, where they float in a constant state of flux. There is a strong presence of beauty, sensuality and emotion in her work, but also disturbance and violence, a juxtaposition that correlates with the complexities of the dynamics between humans and nature. Vernere exercises it through anthropomorphic bodies that can be perceived as sensual beings experiencing a metamorphosis. Just as in some ancient story, they transform from human bodies into stems with blossoms, the bark of a tree, and buds ready to unfold. Mixing ideas that could be attributed to ecofeminism and body identity, she explores her relationships with nature and landscape, dives deep into new readings of ancient myths, and revisits the ghosts of the Soviet past through stigmas attached to women’s sexuality.

The most recognisable and most frequently encountered form in Vernere’s work is the vulva, which represents the interplay between feminine power and nature, and serves as an allegory for her emotions. Sometimes these figural forms are joined by miniature landscapes living inside the ink bodies like shadowlike silhouettes or small windows. These and other elements play in her work as layers or portals, showing the complexities of one’s emotional experience. Landscape is a way to investigate and contemplate the world she inhabits, a way of visualising an entangled state of existence. The works can be viewed as realistic depictions of natural forms, and simultaneously perceived as abstractions that transport the viewer’s perception to a more imaginative place.

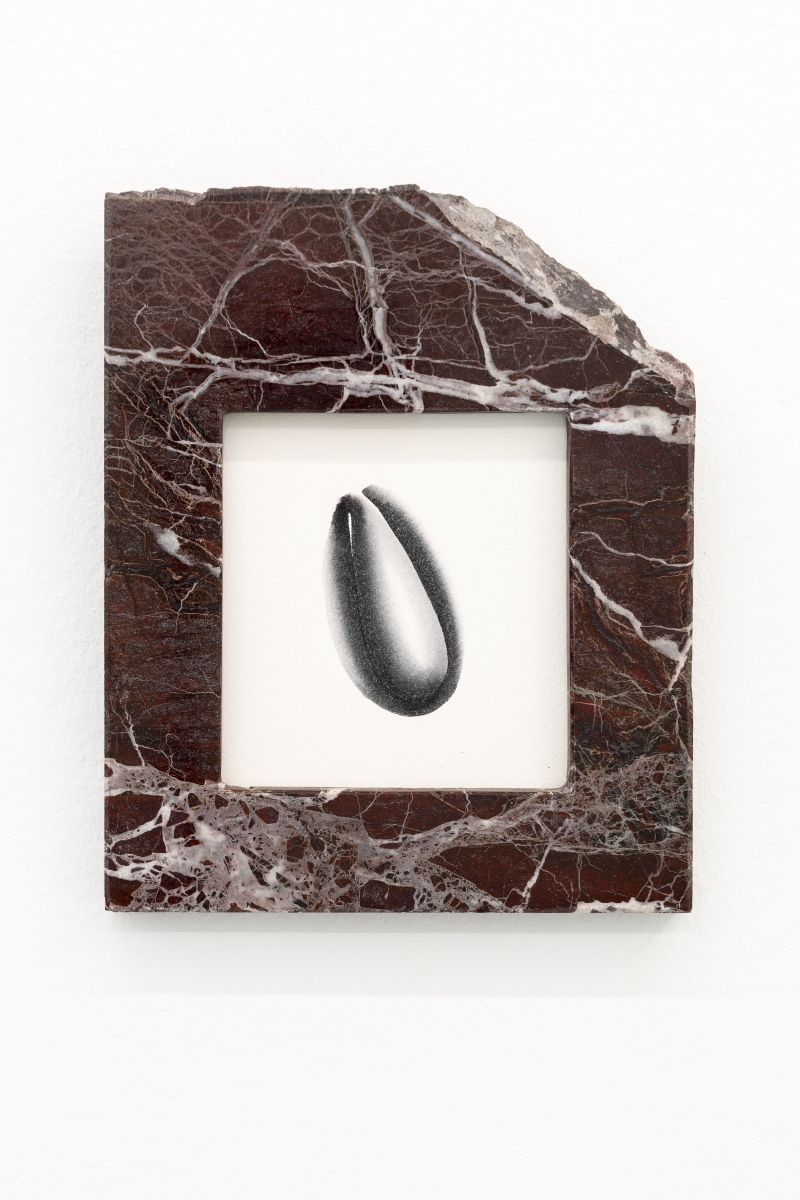

Vernere’s works have a very defined plastic quality, which she has recently been exercising off the plane by using various materials and creating installations in space. She also uses discarded materials, working with leftovers from marble blocks. It is considered a valuable and popular material for creating luxurious walls and floors in bathrooms and islands in kitchens. Left-over or defective parts are discarded like road rock. The artist uses this once luxurious, now unwanted, material, and joins it with her ink bodies. Traces of life experiences are melted together in one entangled piece, embracing it with all its flaws and vulnerabilities.

Vernere is no newcomer to the Latvian art scene. However, her work of the past few years has put her on the map of Latvian art as an artist with a promising future. She is actively exhibiting her work in solo and group shows, most recently in ‘Don’t Cry! Feminist Perspectives in Latvian Art: 1965–2023’ (2023) and ‘In the Name of Desire’ (2024) at the Latvian National Museum of Art. She is studying for a professional doctorate at the Art Academy of Latvia, and runs the Academy’s experimental art space Pilot. Reproductions of her work have appeared in various publications. Since spring 2024, Vernere has been represented by the Kogo Gallery in Tartu.

View from group exhibition Triquetra at Kogo Gallery, Tartu, 2023. Photo: Roman-Sten Tõnissoo.

Sabīne Vernere. BUD. 2023. Indian ink on paper, marble. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

ŠP: The past year has been an important one for you. You took part in ‘Don’t Cry! Feminist Perspectives in Latvian Art: 1965–2023’ at the Latvian National Museum of Art (LNMA), and you also had the solo exhibition ‘Angles Morts’ (Blind Spots) at the Gallery of the Artists’ Union of Latvia, where your work was displayed side by side with that of several important Latvian artists from the 1970s and 1980s in the Soviet era. You also participated in the Triquetra group exhibition at the Kogo Gallery in Tartu in Estonia. After the exhibition ‘Angles Morts’ the LNMA decided to acquire two of your works, Medusa(2022) and Tangled Legs (2023). This exhibition was also nominated for the Purvītis Prize.

You have been active on the Latvian art scene for more than ten years, but it seems that the last few years have allowed you to hit the ground running and come out with several persuasive projects, at the same time as increasing your visibility on the local cultural scene. Is this the moment in your creative practice when certain ideas and ways of form making are polished, and you have the opportunity to showcase them publicly in different ways, or is it just a coincidence, and this appreciation has come naturally, like the sweet fruits of long work?

SV: Thank you for the wonderful summary. In the rhythm of everyday life, everything that has happened becomes forgotten, the struggle in front of you is all that matters. During and after my studies, like many young artists, I had to find a way to work. It took me a while to understand how to deal with the world around me in my artistic practice. I started asking different questions, and it seems that in the last few years these questions have started to resonate more with the people around me. Of course, gaining recognition also gives me strength and confidence. An example of this is getting the year-long scholarship [the Latvian State Culture Capital Foundation’s Scholarship for promoting creative work].

ŠP: When did this turning point in your career take place?

SV: Actually, I can pinpoint it quite precisely. After graduating from the Academy, I had a period of exploration. There was a moment when I thought that maybe I shouldn’t do art at all. I never won any prizes or open competitions, there was no evidence I could succeed. I have been given various opportunities, such as residencies and support grants, for which I worked hard and am very grateful. The first turning point happened when I decided that I was going to do this for myself, because it brings me joy. This way I took the pressure off what I was doing. For a very long time, I didn’t mix work, where I earned money, with my creative practice. Maybe it was a kind of self-defence mechanism in case it didn’t work out, a kind of self-deception. And then there was a second breaking point, in January a year ago, when I made the decision, okay, I want to do this and only this, so that all my energy and focus and mind and my entire being is in it. Shortly afterwards I got the ‘big scholarship’. I decided to do a solo show at the Artists’ Union of Latvia. I had been thinking about it for a long time, but I was kind of afraid. Obviously, nothing happens if you don’t work very hard. When I felt I couldn’t do it any more, I pushed myself harder. I persuaded myself to go to the studio the day after the party. I have seen many times in my life that hard work pays off.

ŠP: That’s interesting. You allowed yourself to reboot after your studies at the Art Academy of Latvia to overcome this moment of crisis.

SV: I always knew things would be difficult after I graduated. Everyone knows that’s the case. After the Academy, I applied for an Erasmus internship in Antwerp, where I spent about nine months. I made this pact with myself that I wouldn’t push myself to do art, I would allow myself to do nothing during that time; a very luxurious situation, actually. I wanted to see what I come up with when I do nothing. Completely, without any expectations.

Sabīne Vernere. 1306 ll from series New Works. 2021. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

ŠP: It was, of course, no accident that your works were included in the exhibition at the museum. Your art is appreciated locally due to your direct feminist perspective. At the same time, your work retains a certain level of abstraction and symbolism that allows for a wide variety of readings. They seem deeply personal, emotional, feminine and sensitive, in a new, empowering and very sexy way, where the female voice is unabashedly present. It’s all somehow natural and fluid, like your ink paintings, and it has also brought you into the Latvian feminist art circle. Artists on the Latvian art scene don’t always wear the labels ‘feminine art’ or ‘feminist art’ with particular enthusiasm, seeing them as overly confining, political or even deprecating. What do you think about these views that are directed towards your art? Do you have a desire to position yourself in this way?

SV: At the beginning, I felt a resistance to the feminist label. But now I can say, with my chest puffed out, yes, I belong to this discourse. I need to celebrate women’s power. For me, feminism is a celebration of fragile strength and beauty, a celebration of differences. Of course, without ignoring all the problems that are present. It’s all there. In interrogating the world through my artistic practice, I always keep the power of feminine energy as my core. The way your inner power can change the world.

ŠP: You say you felt some resistance at first. Why?

SV: Yes, it took some time to truly understand feminism. This included exposure to many artists who interpret feminist ideas in different ways. When you study, you only learn about the most prominent, blatant examples. These didn’t fit in with the way I felt. We needed time to understand each other.

ŠP: Your work is associated with sexuality and the corporeal, but you have repeatedly emphasised that what interests you is nature and landscape. Looking at your work for a longer time, the corporeal outlines seem to transform into flower stems or tree branches, buds and roots, and the fuzzy parts even start to resemble mycelia. At some point, you started incorporating natural landscapes into your work, also in the form of small rectilinear formats, reminiscent of mise-en-scenes within a larger narrative, or windows through which to peer into another, less turbulent, world. Can you tell us more about your relationship with nature and its presence in your work?

SV: Yes, they have always gone hand in hand. I’m interested in nature and sexuality, and sexuality in nature and in people. I think it’s all very interconnected. Sexuality comes naturally from nature, it’s not culture. When a person thinks about sex, and thus indirectly, subconsciously, about reproduction, the region in the brain that is responsible for thoughts about death and mortality is activated. When a person thinks about sex, they are subconsciously aware that they are mortal, that they are not part of the infinite cycles of nature. Culture, on the other hand, is something constructed by human beings. It offers the possibility of participating in processes that go beyond the human lifespan, and, to a certain extent, makes one feel part of something ‘immortal’. For me personally, nature is very important. It is a way of restarting myself, of putting my thoughts in order. And then there are landscapes that have some sort of power that you can go back to. There are specific locations that I inlay in my ink-drawn bodies, using them as empowering symbols.

Sabīne Vernere. Body Intuition. 2023. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

ŠP: The corporeal and the landscape in your work are constantly undergoing new metamorphoses, and are suggestive of ancient Greek mythology, which is currently of great interest to you. You seem to be drawn to the representation and analysis of the role of women in Greek mythology, to women’s stories. This is a topic that you are further elaborating on as a part of your professional doctoral studies at the Art Academy of Latvia. Can you tell us more about this interest? What sparked it, and where has it led you up to now?

SV: I’ve loved making summaries and lists ever since I was a child. I still do it to a certain extent in my creative practice. As a child, I had a notebook where I would write down the colour of the cars that were passing by outside the window, and what commercials were on television. I was an only child, and spent a lot of time at my grandmother’s, where I started reading The Golden Fleece, a book of Greek myths. I cracked it, and realised that it was all very complicated. There are gods, titans and demigods who are related to each other. As a child, I realised that making a summary of it was out of the question for me.

Greek mythology is also a kind of international language for Western culture, in which it is possible to have a conversation just by outlining the basic context. For example, if someone talks about a certain myth, it’s clear what human emotions and human relationships are involved, and as an artist you can then go one step further in your work, because the foundation has already been laid for you. And that’s what has always interested me. Later on, it kind of unravelled in this amusing way. I wanted to read Ulysses, but I found out that Ulysses is based on The Odyssey. I discovered that The Odyssey was the second part of The Iliad. Then I read both books, got hooked, and didn’t get round to reading Ulysses, of course. That is where my interest in ancient Greek myths came from. I started researching them more, reading and listening to podcasts and lectures.

Then, at some point, I started to feel this sense of injustice, because the stories didn’t resonate with me as a woman. I felt a kind of bodily resistance to the content of the stories. I started thinking how fundamental these myths are to the world we live in, and that for thousands of years women and female sexuality have been represented in a certain way, and this has definitely left its mark. I typically examine sexuality in my practice, and I reached a point where I started to interrogate the representation of female sexuality. Greek mythology clicked with me as a tool that shows very clearly the very roots of the world today. And I learned, much to my delight, that I was not the only one, and that for the last 40 years or so, women classicists have been addressing this segment seriously with a feminist outlook. Ancient Greek myths are being translated and rewritten by women. If knowledge is passed down through the millennia in stories that men tell to other men, all sorts of glitches can arise. Women classicists reinterpreted the myths, translated them, and gave them their own voice. Myths are still alive today because they are universal. They can be adapted to all sorts of situations in life, to one’s own inner processes, and they help us understand things.

You see, I am fully immersed in this world, reading different theories and interpretations and new translations, learning about the ways these myths have shaped social attitudes, ideas about the good woman, the bad woman, the woman monster. All women who have been disobedient are punished or made into monsters in Greek mythology. This immediately provides a wonderful framework for a whole host of problems. This history is now being written anew, and I am observing the process with great pleasure and enthusiasm. At the same time, I seek to connect it with the world around me; like, to what extent do these woman monsters, strong, independent, sexual women, live inside me, inside my head? Who is the Perseus, the symbol of patriarchy, that comes to behead the Medusa, the symbol of power, in my mind, in my friends’ minds, in society around me?

Sabīne Vernere. From the series Sirens, Medusa and the Isle of Lotus-Eaters. 2022. Ink on paper. From the collection of Latvian National Museum of Art.

Sabīne Vernere. From the series Sirens, Medusa and the Isle of Lotus-Eaters. 2022. Ink on paper. From the collection of Latvian National Museum of Art.

ŠP: Apart from Medusa, have other stories from Ancient Greek mythology caught your attention?

SV: Many have. I am currently interested in the story of the Sirens, the temptresses. In the context of these myths, I am interested in exploring sexuality as an instrument, and asking who owns this instrument of sexuality, does it belong to women themselves? To put it briefly, the Sirens live on an island in the sea, where they sing an irresistible song. The most famous in this context is the story of Odysseus, in which he and his men sail past the island. They sing a song, and the men jump overboard because the song contains a promise. Nobody knows what the promise was about. At some point in the history of art, these Siren women become sexualised as evil temptresses. I, on the other hand, am interested in the question why they sing. Perhaps they are singing to themselves rather than to the men. Why are they considered monsters? They are not killing anyone, the men jumped overboard themselves. That is something that interests me at the moment.

Another story I’m focusing on is that of Pandora. Kalon kakon, the beautiful-evil thing. Prometheus gives fire to people, and Zeus punishes humanity by creating woman. He gives men one bad thing (woman) for one good thing (fire). Before her, there were only men living on the Earth. And he makes all the gods give something to the woman. Aphrodite gives her seductive abilities, beautiful clothes, a beautiful body, and body language. He wants to give men something that they cannot live with and cannot live without: both ways there is suffering. These images, Pandora, the guilty one, the punishment of the gods, Medusa and the fear of sexuality, and the Sirens, the temptresses, these are the images I am interested in exploring through Greek mythology. By the way, Pandora did not have a box, she had a vase, an amphora. It’s a mistranslation. Another interesting topic is the Amazons. They were women who lived as equals to men, and for that reason they seemed very sexy to Greek men. In order to be allowed to marry, an Amazon had to have killed a man in combat. I read about this recently, I think it’s an amazing titbit.

Sabīne Vernere solo exhibition Angles Morts at Artist Union Gallery, Riga, 2023. Photo: Ansis Starks.

Sabīne Vernere solo exhibition Angles Morts at Artist Union Gallery, Riga, 2023. Photo: Ansis Starks.

Sabīne Vernere solo exhibition Angles Morts at Artist Union Gallery, Riga, 2023. Photo: Ansis Starks.

ŠP: The exhibition ‘Angles Morts’ at the Artists’ Union of Latvia, as well as your other projects, make me think about your relationship with the past, and the way you choose to talk about it. Why are you interested in highlighting and interpreting this material, and is your interest focused on a particular topic, or on the blind spot itself, its ignorance, its lack of understanding?

SV: I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and as I’m a year and a half into my PhD, I have to look at my practice as a researcher as well. Whereas before I was simply working and had only a vague idea of what my artistic methodologies were, I am now looking at it much more scrupulously, and I’ve come up with some answers.

What I got from ‘Angles Morts’ was an idea of the way I do my work. Looking at myself, looking at the world around me, I have always asked questions about nature, sexuality and human relationships, and over time these questions have become more and more complex. In the case of the exhibition, the big question I came to was: what is my place on the Latvian art scene, what are the foundations on which I stand? What is my context? The Soviet regime, the 1990s, the artists whose work I grew up looking at, all of this has influenced and shaped the way I am. I really want the environment I’m in now to become better. The question is, what do I do, where do I go? Should I go into education, into politics? Where should I pitch in to improve the world around me? I made the decision a long time ago that I wanted to live in Latvia, and I consider it my duty to do everything I can to make things better. Somehow, it all came together in the following point: in order to find answers to these many questions, we need to have a conversation with this exact place and this exact collection. So I chose the Latvian Artists’ Union, with all its politically and geographically complicated history, as the larger framework. And then, as I delved into the details, I decided to have a direct conversation with the place, with the collection. There’s a lot to this building and its collection. And then, intuitively, reading and gathering information about it all, I chose certain works for the exhibition. Some at the very beginning, some of them later, and some even at the very last minute, as tends to happen when you have exhibitions.

In the process, I started forming questions about the role of the female artist. I began approaching the material in a more intimate way: the way I feel, the way this role has been influenced by time, and the way it has changed today. So somehow I slowly got a context for all the size, the infrastructures, the institutions, the artists, and the recent art history that I’m standing in the middle of. To an extent, it was probably self-therapy and clearing things up for myself. But I also had a great respect and reverence for what the thing I was working with actually was. I really think the collection of the Artists’ Union is a miracle, as are the lives of its artists. There is a generation that has grown up without knowing anything about the Artists’ Union and what in fact happened there. We don’t have studies and art history books about it.

Sabīne Vernere. Vulva. 2020. Indian ink on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

Sabīne Vernere. From series Sirens, Medusa and the Isle of Lotus-Eaters. 2022. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

ŠP: A book was published about it a long time ago, but we definitely need a new monograph.

SV: I often think that artists lack a common voice, a sense of community, including political decisions. A united voice that stands up for their rights. Everybody is doing good work, great work, but somehow they’re all doing it one by one, or in these little clusters. Working on this project, it seemed that there was a lack of being together, so it was important for me to do it all there.

Then, while working on this project, the theory of the gaze was important to me, which was brought to me by [the poet and translator] Lauris Veips, who also did research on my work Medusa. His MA thesis discussed the theory of the gaze that appears on the wings of a butterfly, which paralyses its attackers in self-defence. And this is consistent with my own work Medusa. I see that the collection of the Artists’ Union also paralyses us. Dobičins [Igors Dobičins, the head of the Artists’ Union] laughed when I went to his office several times to talk about the exhibition: ‘Well, I realise now, you simply want to be friends.’ And in a way I do, I want to be friends with the recent past. The primary impulse for this exhibition was the will to make things better, and I also asked myself a lot of questions.

ŠP: Can you give us a little insight into how you selected the works from the collection of the Artists’ Union of Latvia?

SV: When I started working a year before the exhibition opened, I realised that I would not be able to do scientific research. The task would require a team of artists and art historians working on it. But I went there, sat in front of the collection, and tried to understand what was happening to me on a bodily level. In my practice, it is often the case that there is a bodily impulse from the beginning. Of course, it is the women artists that resonate with me most, such as Maija Tabaka’s work, Līga Purmale’s empty room, and Lidija Auza, a wonderful little-known artist. They all have their own aspects that interest me. This choice was, of course, influenced by the various stories about what it means to be a woman artist. In one of the first painting lessons I ever had, my first teacher Aija Jurjāne sat us in a line, and said: ‘It’s difficult to be a woman artist.’ She was preparing us mentally.

ŠP: Your art education can be perceived as very traditional in the Latvian context. You studied at the Janis Rozentāls Riga Art School, and then at the Art Academy of Latvia, where you obtained your BA and MA degrees in painting. At the same time, early on in your career, ink and paper became an important means of expression. Can you tell us about your choice to study art and painting, and how you decided to focus on ink and watercolour techniques, instead of oils or digital painting, for example? What is it that drives you to go outside the boundaries of certain art forms and techniques?

SV: When I was about two and a half years old, an art school opened in Kuldīga [the artist’s hometown], and I was enrolled in its preparatory group. I hadn’t even learned to speak properly yet. Ever since then, I consistently attended the children’s art school, and then the Rozentāls Art School. I don’t even know what it’s like not to do so. I have no memories of a time when I didn’t. We went to Roži [translator’s note: the nickname for the Rozentāls Art School] from Kuldīga Children’s Art School on an excursion. As I went into the building, I realised this was where I was going to study. I didn’t analyse that path much, to be honest, and for a very long time I just did it without thinking.

As for the medium … I turned to paper and ink for very rational reasons. I was on an Erasmus exchange in Croatia, and I realised that I wouldn’t be able to take any canvases or oils with me anywhere. So I started working with paper and watercolour. I also understood that I’m quite impatient when it comes to making art. I started with oils, and then moved on to large formats and acrylic, and then to watercolour, so I could cover the bigger areas faster. I eventually gave up watercolour and stuck to black ink. I like how direct and simple the material is. There is nothing superfluous, everything happens bodily and intuitively. Antoni Tàpies has a cool quote, that when you’re working with materials that are fast, that spread and dry quickly, your mind is unable to keep up. The hand wields the flowing ink so quickly that the mind can’t be there. It’s like a format that was made for me. It’s a quick, intuitive, bodily way of creating forms.

I had an interesting turning point with the exhibition ‘O’ (2021) in the Tu Jau Zini Kur art space, which was the first time I worked directly with space. Up to that point, I had been working with the image. With ‘O’ I wanted to ‘throw’ the body, which I usually represent on paper, into reality as well. The viewer can feel their body as their shadow slides across the paper, clearly aware of their own corporeality. It was the first time I worked with space, and I realised I was very interested and liked it.

Sabīne Vernere. Impossible Runner from series Angles Morts. 2023. Ink on paper – stretched on wooden frame. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

Sabīne Vernere solo exhibition Brivibas St. 40, Riga, 2020. Photo: Peteris Viksna.

ŠP: You have said more than once that there’s a plastic quality to your work. Recently, in a private conversation, you also suggested that perhaps it was time to turn to sculpture, a turn that has by now become evident in your marble frameworks, as well as in your installation ink paintings. Can you tell us a bit more about this aspect of your art, and maybe some of your ideas for the future?

SV: When I create images in ink, I see them as three-dimensional objects. I don’t think my work is just limited to the plane. I don’t think of it as flat. I already see it in movement. I sense it from all sides, and in that sense my work is already very sculptural. Actually, the creative process, especially if I’m working on a large scale, has a profound bodily side. Applying a large area of water and then adding ink pigment to it is by itself a method of creating form on paper. Of course, I have fantasies of what it would look like in physical reality, in three dimensions. Francis Bacon had this text about how it was enough for him just to think about sculpture as he was painting. I mean, the fact that I think about it in itself changes my practice, and helps me.

ŠP: Apart from your direct creative work, you also run the Pilot exhibition space at the Art Academy of Latvia. You have also had the opportunity to work as an intern in commercial galleries in Belgium. Considering that nowadays an artist has to be able to be a good manager and entrepreneur, these seem like very useful experiences. What do you think about your own experience of working in galleries and art spaces? In the case of Pilot, isn’t it also the case that you have a natural desire to collaborate, to support other artists, as in your last solo show?

SV: The internship was a very deliberate decision. Latvia has developed an unusual, unique model, where commercial art institutions work in a hybrid format. This doesn’t give a full understanding of how work relationships are formed, what the gallery expects from the artist, or the way it functions. It was a very interesting experience. At the beginning, it was difficult for me to understand how it could be that a gallery is a shop. It was a wonderful learning experience. I got a lot out of it, and came to understand many things that I think are missing from our education system.

When I came back, the Art Academy of Latvia offered me the opportunity to run Pilot, an experimental student space. I was hesitant at first, because it’s a difficult job. But I accepted, because I wanted to pass on my new knowledge to as many young students as possible. It’s an exhibition space for learning, and every two months I meet someone who has never done an exhibition, and then we can go through the process together and talk about what it is and what it means. I think it’s very important to have this practical learning space here.

ŠP: In past interviews you have said that you try not to plan too far ahead into the future. Is that still the case now, or has something changed?

SV: (Laughs) Just recently I was talking with friends about how unusual it is to know what you’re going to do in a year and a half. Is that a sign of being an adult? Because for me it’s something new. But yes, I know what I’m going to do, and I plan for the future. I’m making a lot of plans. I’m currently looking forward to another year of professional doctoral studies. I’m going to the Cité residency in Paris. I’m also planning a solo show in Madona in the summer at the Maboca [art festival] gallery Visuma Centrs 2, which I await with great enthusiasm and joy. The main thing I will be doing is immersing myself in the research necessary for my PhD studies. I’m preparing myself, because I have to conclude my PhD with an exhibition. I also have a wonderful plan with the Savvaļa [open-air art space] team. We will carry out an initiative of mine, creating an exhibition of contemporary art for children in different regions of Latvia.

Sabīne Vernere. CLIMB. 2023. Indian ink on paper, marble. Courtesy of the artist and Kogo Gallery.

Sabīne Vernere solo show O! at TUR gallery, Riga, 2021. Photo: Aleksejs Beļeckis.