Curated By is an annual festival in Vienna that takes place across 24 of the city’s commercial galleries. Provided with funds to select an international curator, the festival aims to bring new voices and visions to the scene. Now in its 13th year, the festival has become an established feature in the Viennese art calendar. Each year features one curator who is invited to provide a general theme for all the exhibitions. This year’s ‘Impulsgeber’ is the Belgian curator and writer Dieter Roelstraete, who proposed the theme ‘Kelet’, which is Hungarian for ‘East’.

The topic in itself is repetitive and uninspiring in a city that describes its geographical location as ‘a gateway to the east’, and which simultaneously hosts the commercial art fair Vienna Contemporary, which for years has featured artists and galleries from Central and Eastern Europe. Roelstraete explains that he arrived at this concept through a Hungarian literary magazine published in the early 20th century called Nyugat,[1] Hungarian for ‘West’. Based on this title, he claims that ‘artists and writers starred [sic] for avant-garde action in the eastern backwaters of the Dual Monarchy or neighbouring czarist Russia were right, of course, to always turn west for glimpses of the future’.[2] Roelstraete’s hope is that an ‘East’ defined by the land between ‘Bratislava and Khabarovsk’ will be framed as a panoramic picture of ‘an imaginary land bathed in the sun of artistic riches and renewal’.[3]

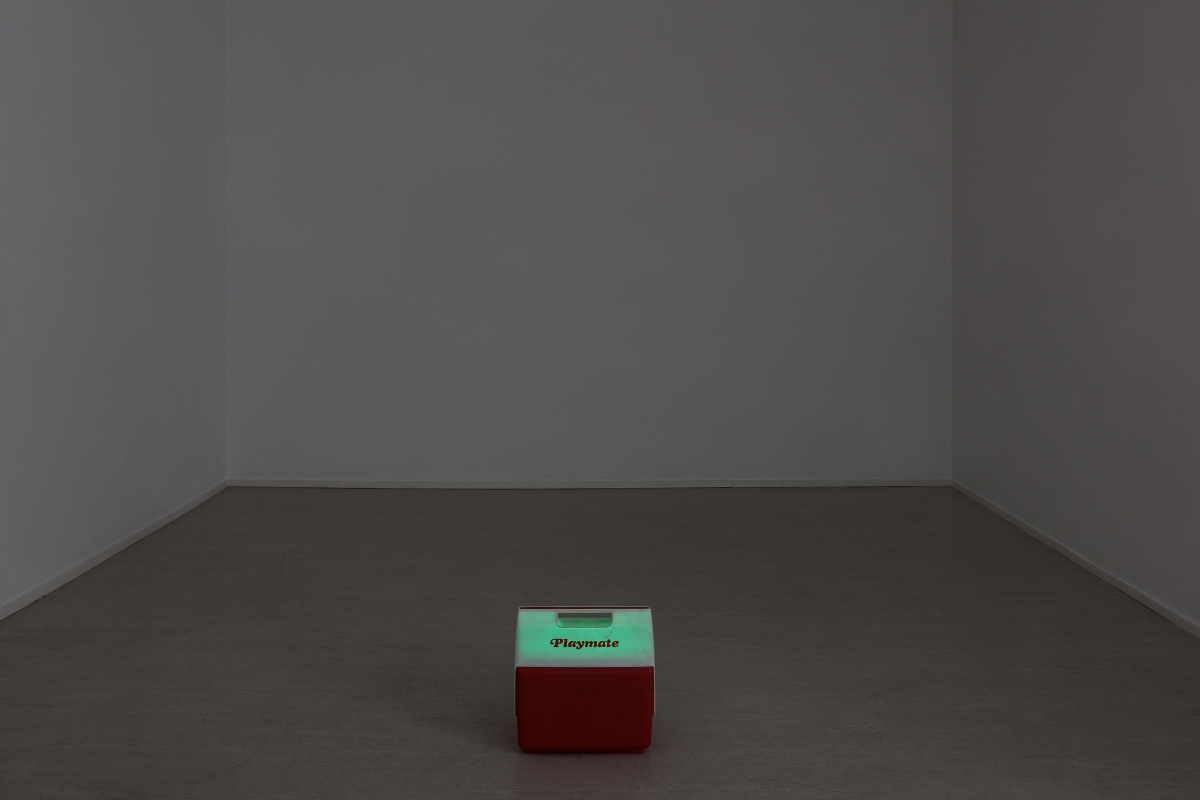

EXILE Extraneous curatedby 2022. Manuela Moscardini

In a round table addressing this questionable topic, the Hungarian curators Lívia Páldi and Róna Kapeczky called it ‘a poetic mistake’, but it is safe to say that it is more than that. As a visiting Hungarian curator pointed out during the opening days,[4] others thought of ‘Kelet’ a century before Roelstraete turned the word around, even if he fails to mention this in the text. Two opposition magazines were set up by artists and writers to counter Nyugat, called Napkelet and Kelet Népe. They were published in Budapest in the 1920s and 1930s.[5] But the ‘East’ which the word Kelet referenced in the context of the early 20th century was not the one that Roelstraete imagines when writing from Chicago, an ‘East’ that for him compresses an enormous and certainly not imaginary land. Instead, Kelet pointed to the political current of Turanism, which referred to an ethnic concept of a Turkic Ural-Altaic people from whom the Hungarians are mythically descended. This is still a source of inspiration for Hungarian political leaders, including Viktor Orbán.[6] As such, Kelet stood in opposition to the spreading notions of surrounding pan-Slavism at the time.[7]

The unfortunate wording of the introductory text has, however, made for a rich context to reflect on the enduring blindness of the orientalism and infantilisation by the ‘west’ of a part of Europe that it is still reluctant to accept as a place where contemporary thought is produced. An area where, in contrast, the art history discourse has for decades refuted simplistic and generalised assertions around this geographical region. Several curators responded in creative and subtle ways to rebuke the outdated dualist dichotomy of East versus West. Some opted to break the strict geographical confines proposed by Roelstraete, and thus create more complex ways to discuss geography and identity, while others responded more directly to the provocation.

Alessandro Rabottini’s exhibition ‘Water Being Washed Away’ at Hubert Winter contests the prompt by exhibiting artists who reflect on their own places of origin from different geographical locations. The intricate complexities of identity, memory and belonging emerge in works that take over the space, engaging a myriad of sensations. Latifa Echakhch works with a simple food colouring used to emulate the more expensive saffron in North Africa. Entitled Gaya (E102) Horizon, the work confronts identity and economy through communal experiences such as food and the disappearing landscape of one’s origins. Phillip Lai’s Expulsions are hand-made vessels that resemble oxygen tanks or air-filled buoys. Emphasising the contrast between loss and retention, all the artworks in this show speak about distance as a narrator from one’s own homeland. We live in a world that is far away from the early discussions of globalisation, a time in which identity and circulation are so entangled that they cannot be understood as a ‘here’ and ‘there’.

Galerie Hubert Winter. Philipp Lai

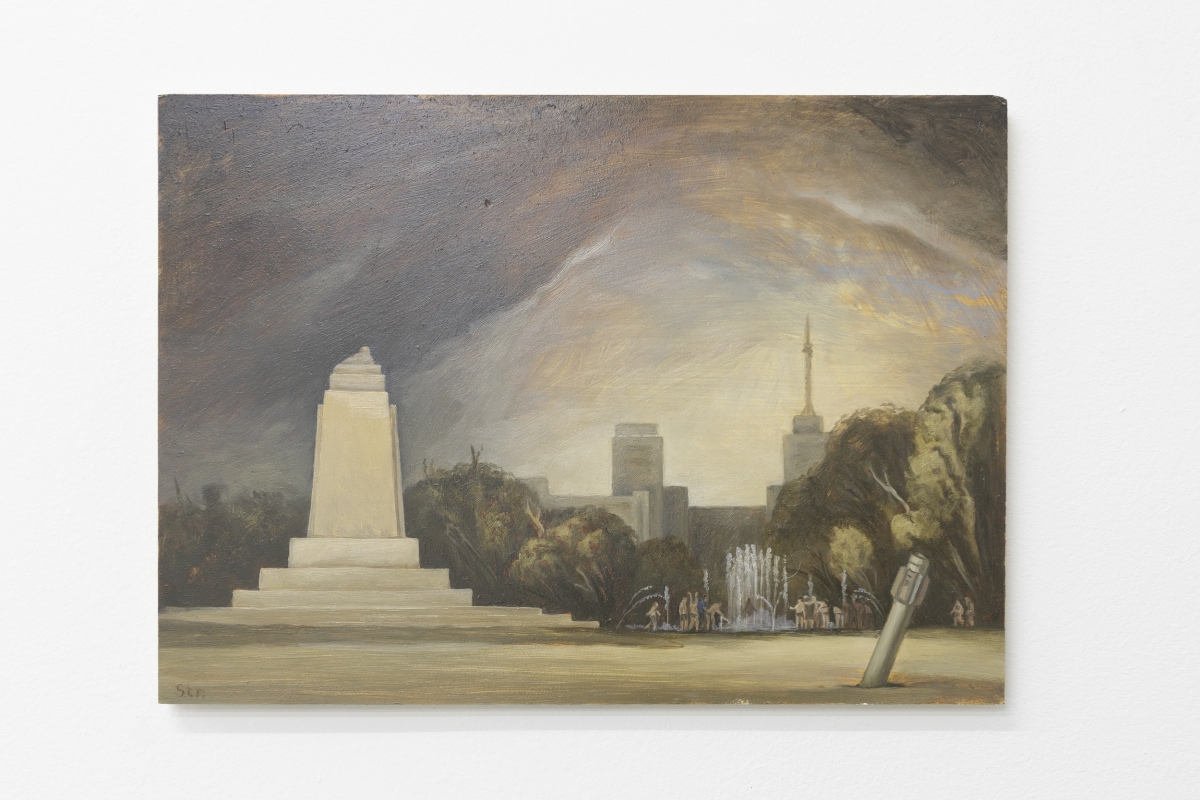

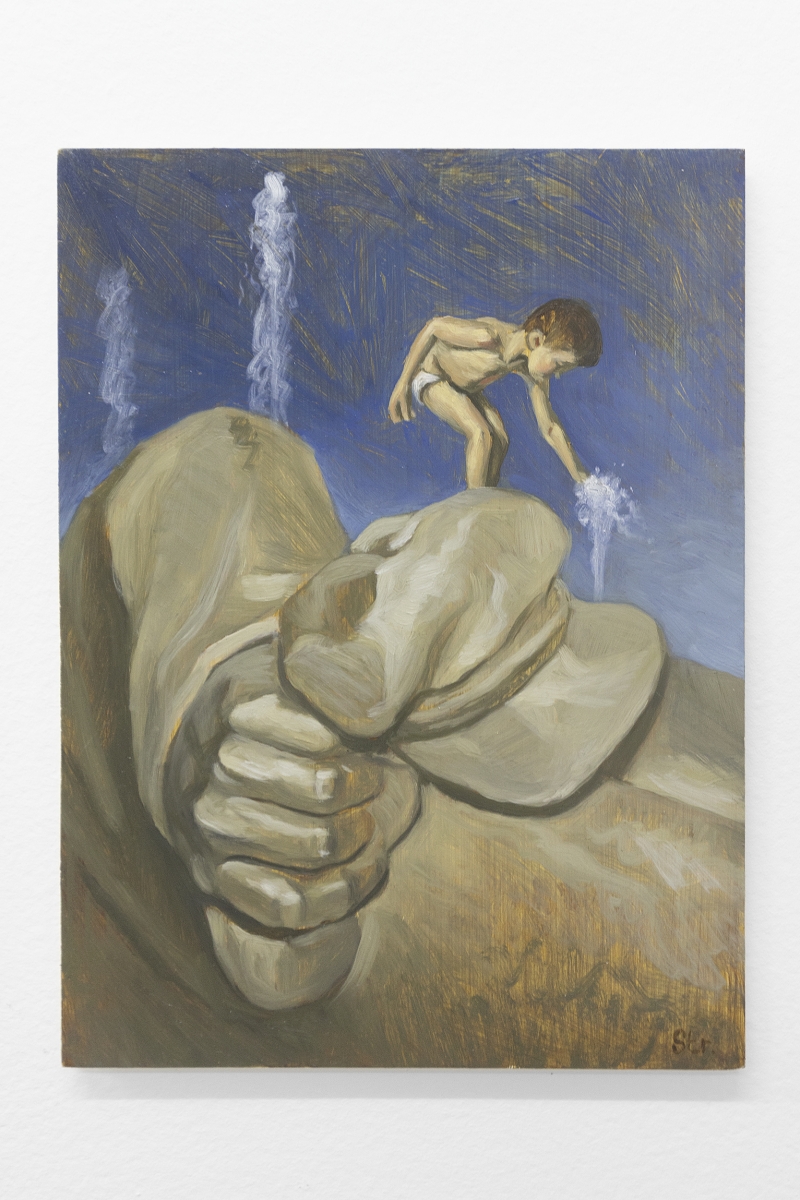

Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani touch on the themes of refuge and home that currently affect millions of Ukrainian refugees, as well as other people who suffer from imperialist aggression and war around the world. The expert and delicate paintings by Nazar Strelyaev-Nazarko play on romantic notions of childhood amid the reality of unexploded missiles and destroyed buildings in his home town of Kharkiv. Acts of tenderness unfold between children and parents in new ruins of public spaces such as Plóshcha Svobódy (Freedom Square), which once had a statue of Lenin, and, until recently, a European fountain designed by Italian architects. Next to it, the fountain, as a space for community and desire, surfaces again in the ceramic models by Margherita Moscardini, whose multiple sculptural pieces occupy Exile Gallery’s downstairs space. The connection between community and sociality surface in these private monuments that were built by Syrian refugees in Jordan to create a semblance of home.

Hana Ostan Ožbolt’s exhibition ‘I Had a Dog and a Cat’ at Georg Kargl Fine Arts is accompanied by a text written by the curator that problematises the festival’s theme in a direct way, contrasting it with the delicate nature of the surrounding artworks. The dog and cat in the title refer to the outdated binary system in Roelstraete’s text about the ‘East’ and ‘West’, male and female, or any other systems of othering that are reduced to two simple categories for the sake of making it understandable to children. As a source of inspiration, she cites the Czech author and playwright Karel Čapek, who said it is not embarrassing to write for an audience of children, it is writing badly for children that makes the act undignified.[8] In this spirit, Ostan Ožbolt has prepared a subtle and poetic exhibition based on the duality of lightness and darkness in a collaborative exhibition design made together with the artist David Fesl based on natural sunlight. The exhibition twists between the corridors and the skylight of Georg Kargl’s space. Within it, Fesl’s work appears like intimate natural monuments behind the delicate layered photographs of Kazuna Taguchi, and the ever-haunting object-collages of Michael E. Smith.

Adomas Narkevičius uses humour and mischief cleverly in order to poke at the text in an exhibition whose title refers directly to ‘The Prompt’. In the Gianni Manhattan Gallery, this exhibition features work by Baltic women artists of various generations to address the elephant in the room in a humorous style. Ola Vasiljeva’s performative and sculptural works play with the stereotype of the mischievous child in the character of Marguerite Duras’ Ernesto, who refuses to learn anything that he does not already know. Here, the mind can play with the idea of ‘the West’ as a stubborn child. Vasiljeva’s gate-like metal cut-out blocks the middle of the gallery like a fence (or iron curtain), splitting the space in two. The historic photographs from the 1970s taken by Milda Drazdauskaitė are humorous and tender depictions of strong women who defy stereotypes of Soviet life through fashion and attitude, which show feminism well in advance of its time. At times, bucolic scenes with cows, farmers and slanting mischievous smiles mock the clichéd romanticism of her (male) contemporaries. Through their unfettered irreverence, these photographs mock any notion of backwardness, and display punk and subculture references in the 1970s Soviet Republics.

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

At the round table organised by Hana Ostan Ožbolt at Georg Kargl, she opened the discussion with a reference to the year 2000, and the way that Manifesta Biennial spoke about Ljubljana at the turn of the millennium. Nothing appears to have changed in the current text. Is it necessary to remain indefinitely complacent about the patronising de-facto neutrality of the heartland of liberal Europe defined by Germany, the Low Countries and France? The best exhibitions at this year’s Curated By challenged these assumptions, whether from the East, South, Above or Below. The prompt is a misplaced hope that has aged poorly as history goes on: Germany is at a moral low after its non-response to the ongoing war in Ukraine, Austria is a neutral non-Nato geographical location that is one of the two EU countries that has not supplied weapons to Ukraine (the other is Hungary).[9] What is certain is that the text says a lot more about the mentality of the ‘West’ than about its neighbours (either East or South), which it is unwilling to see as equal, as complex, or as contemporary.

EXILE Extraneous curatedby 2022. Nazar Strelyaev-Nazarko

EXILE Extraneous curatedby 2022. Nazar Strelyaev-Nazarko

‘I Had a Dog and a Cat’ (David Fesl), curated by Hana Ostan Ozbolt. Installation view. 2022. Courtesy Georg Kargl Fine Arts. © Georg Kargl Fine. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com.

‘I Had a Dog and a Cat’ (Michael E. Smith), curated by Hana Ostan Ozbolt. Installation view. 2022. Courtesy Georg Kargl Fine Arts. © Georg Kargl Fine. Photo: kunst-dokumentation.com.

Galerie Hubert Winter. Latifa Echakhch

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

The Prompt. Milda Drazdauskaitė, Elena Narbutaitė, Ola Vasiljeva, curated by Adomas Narkevičius, installation view GIANNI MANHATTAN, Vienna (2022), photo: kunstdokumentation.com, courtesy the artists and GIANNI MANHATTAN

[1] ‘Nyugat was founded at a time when the world’s undisputed art capitals were western metropolises like Paris and Munich (the rise of New York even further to the west was then still many decades in the making).’

[2] Dieter Roelstraete, ‘Kelet’ (https://curatedby.at/kelet) (accessed 16 September 2022).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Conversation with the curator Kirsztián Gábor Török, 10 September 2022.

[5] Wikipedia entries ‘Kelet Népe’. (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelet_N%C3%A9pe_(foly%C3%B3irat,_1935%E2%80%931942)https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelet_N%C3%A9pe_(foly%C3%B3irat,_1935%E2%80%931942)) and Napkelet. (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napkelet_(foly%C3%B3irat,_1923%E2%80%931940)) accessed 17 September 2022.

[6] György Lázár, ‘Hungary is now part of the Assembly of “Turkic Speaking Nations”’ Hungarian Free Press, 25 November 2018.

[7] Balász Ablonczy, ‘Go East!’ (2021) Indiana University Press. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv21r3q9j) accessed 16 September 2022.

[8] Hana Ostan Ožbolt, exhibition text ‘I Had a Dog and a Cat’ (https://www.georgkargl.com/en/node/13181).

[9] Aljazeera, „Austria commits to neutrality even as Russia destroys Ukraine’ 15 August 2022. (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/15/austrian-neutrality-in-light-of-the-ukraine-war)