Justina Zubaitė-Bundzė (JZ-B): First, I would love to thank you for sitting down with me for this conversation, in the very midst of the final touches for an exhibition which includes painting and film. Let’s start with the title of the exhibition. ‘Monogram’ is a graphic form, a symbol made up from a combination of two or more letters. Typically, they are a person’s initials, a mark of authorship, ownership, or maybe a signature style mark. How do you see it in relation to the artworks in the show, or in relation to the exhibition itself?

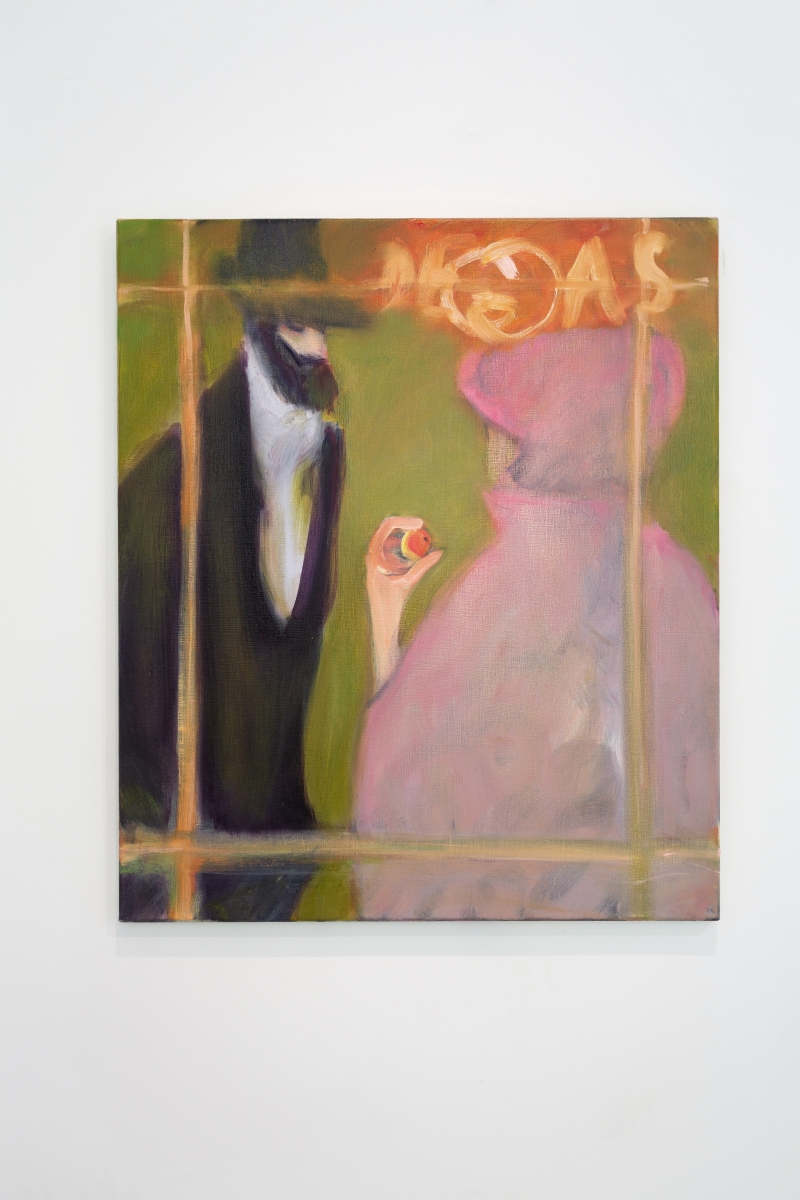

Rosalind Nashashibi (RN): I was working with mirrored motifs, and I started bringing into that a kind of mirrored ‘R’, as a monogram on the side of the painting. I wasn’t thinking about it so much as a signature style, but it’s interesting that you say that, because it can be said to be the mark of the artist who carries through a certain way of looking at the world in different media, be it a film or a painting.

Actually, I am bringing a sign into my work that points to a meaning that is not necessarily accessible in any other way. So the sign in the painting, which might be a double swan or an arabesque or a double R or RN monogram, is obviously a signifier of something else. But in a way, painting is always that signifier of something else which is not actually necessarily located somewhere else. It is a substitute for something that doesn’t otherwise, or ‘otherplace’, exist.

I was thinking more about the reduction of something to a very simple sign, like the process of making motifs in general. We could also describe that reduction as the toss of coins in divination which takes in all of the moment around the thrower, or the process where the whole environment of the maker affects what appears on the canvas.

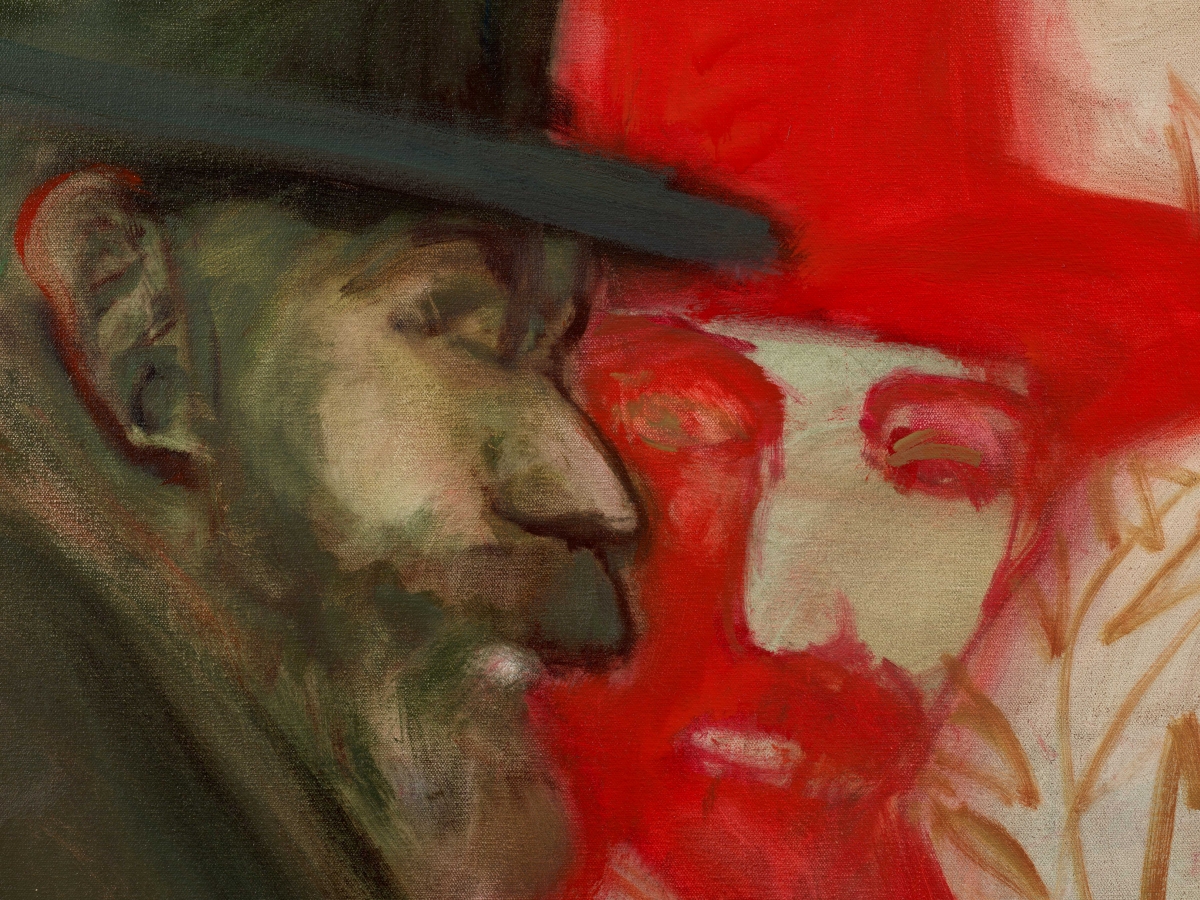

Rosalind Nashashibi, My Demons (after Sickert), detail, 2022.

JZ-B: The reason why I alluded to this slippery territory of the signature style follows from my impressions from both your films and paintings, your ‘conversations’ in artworks with other artists, with, we could say, aesthetic predecessors. What fascinates me each and every time is your attention and care for the artists, art history, collections and other things. It always gives me this wonderful feeling of re-enchanting the practices of art. I thought the monogram might be born from some sort of lineage of forms that comes back, returns, and jumps into your works.

RN: I think it is the same for all artists: whenever you start to make a painting or decide on shots in a film, or edit the shots, there are lots of other paintings and films that are running through your head at that moment. You are always referencing other things or riffing on other things. There is a 16mm animation La signature (Une seconde d’éternité) (1970) by Marcel Broodthaers where you do not see his hand, but you see his initials ‘MB’ being inscribed over and over and over. Without knowing why, I always found this work intriguing. It is very simple, it could be seen very theoretically as just the artist’s signature; but for me it was always more than that. It is some sort of real expression of going into his artist self. Which is usually the starting point for me to make a film or painting, or some investigation … I had forgotten until now, but that work was important.

When I think of intertwining letters, a monogram, it carries within it a whole world-environment, whether it’s the double ‘G’ of Gucci or another fashion label, or the artist’s signature, or some old brand of socks. It brings with it a world of associations, and when it is made into a monogram, that world of associations becomes mythical. Because before it was something that you would have to assemble. You could then say, well, it was about the moment, a socio-political situation where people wanted to be seen wearing pearls and riding horses, or now that almost everyone is wearing sports brands. But when it becomes a monogram, the whole world of associations is in the monogram, and therefore it has already become a myth. Carl Jung said that mythology brings us glamour. Glamour is commonly associated with fashion, but when you think about it as associated with myth, it becomes less reductive, it’s no longer about being glamorous or looking a certain way, or being up to date. It’s more to do with having a deeper connection with myth as an atmosphere around it. Does that make sense?

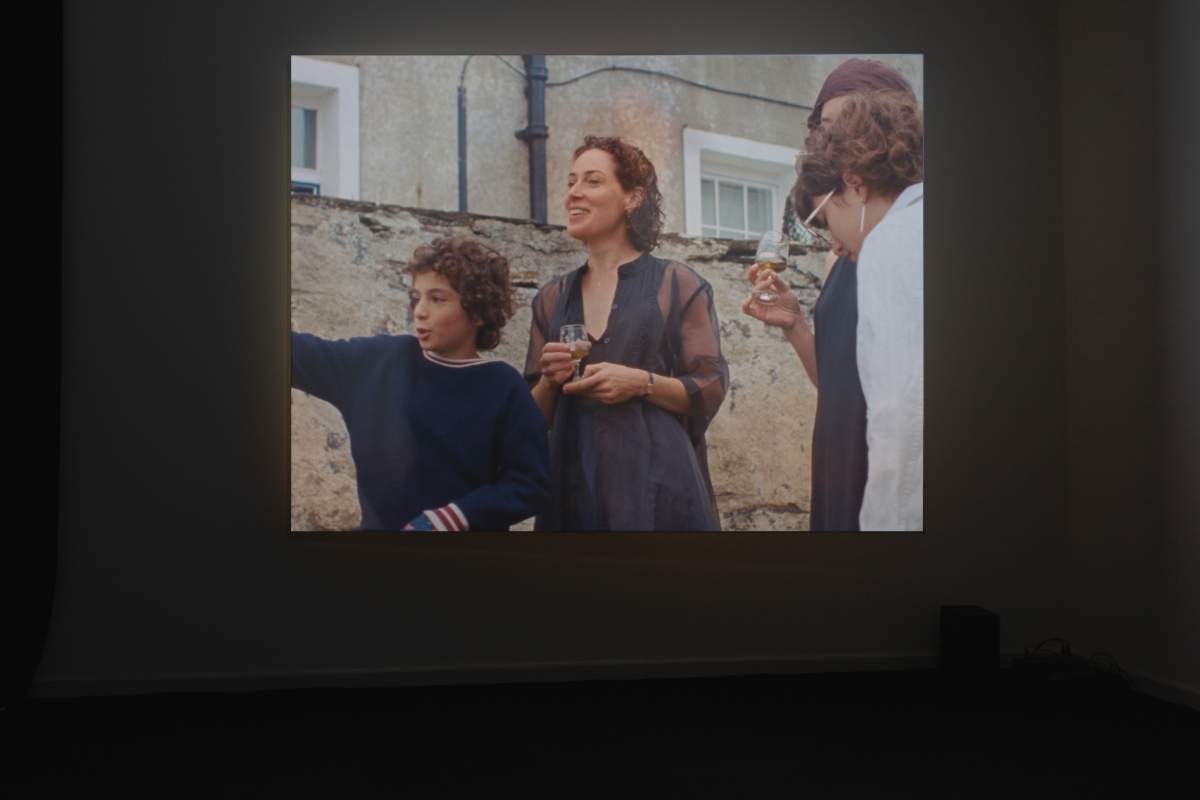

Rosalind Nashashibi, excerpt from ‘Denim Sky’

JZ-B: Oh, that’s an interesting take, I like it! What about Denim Sky, again, a wonderful title for your new film that you are presenting in this exhibition. This film is sometimes called a trilogy, and has been filmed over a long period of time, and, if I am not mistaken, is the longest of your films. You first showed it a few months ago in London, at the National Gallery, where the third part of the film was also filmed. Nida, Preila and Vilnius are also not only locations in it, but also some sort of mythical setting, almost like the characters. Could you please explain the film to readers and visitors to the exhibition?

RN: The project that is now Denim Sky began in 2018, but I always knew it was going to be a long process with different intermediate points. Initially, the idea was to think about different ways of dealing with the situation that I was in, as a fairly recently divorced single parent bringing up two children. The main question I was asking myself was: Who is my community, and what is the way of surviving this [situation] intact, with all the challenges of single parenting, and working as an artist? And how could these things not obliterate each other? My work was taking me away from the family, and on top of that, parenting at that time was very difficult. It is just really hard work. I think that was a basic desire in me: to find out what a community could be, and how being an artist and bringing up children could become more harmonious in relation to each other.

I began by going on a trip with my children and some friends who I felt could share these thoughts and experiences, and explore different ways of living with me. I didn’t expect us to become a commune, but it was more about spending time together, with the kids and the friends who were really my peers. I was thinking about that community through the lens of science-fiction, which often involves space travelling. When you have a crew, the crew needs to work together, they need to be aligned with each other, they need to be able to function as a group. Inspired by Ursula Le Guin’s The Shobies’ Story (1990), we worked with the idea of a space crew testing a new kind of space travel using non-linear time. We tested out various possible scenarios that could happen in a nonlinear environment. The film is partly about that: what would happen to the relationships between people and family relations if time became non-linear. In the film everything is real in a sense: we were filming ourselves and each other, having discussions, but there are also bits that we staged and stories that we told.

We shot ‘Part One: Where there is a joyous mood, there a comrade will appear to share a glass of wine’ in Nida in April 2018. Some of ‘Part Two: The moon is nearly at the full. A team horse goes astray’ was shot in Edinburgh in 2019 in summer, and other bits back in Pervalka in January 2019. And then we did the final parts in the still restricted summer of 2021 at the National Gallery in London, and then in Orkney, Scotland. Obviously, the pandemic came in between, so we had a long gap where we didn’t see each other and didn’t discuss it. And really all the way through the only discussions that we had about the film were mainly between Elena Narbutaitė and me. But a lot of it wasn’t discussed, it was just spontaneously lived and done.

JZ-B: In the third part there is a really beautiful scene where after a long time you meet Elena in London and one of you comments ‘There is a feeling that something has changed’ and then both of you talk about trying not to come back to the relationship that you had before but how you are rather willing to explore the new setting. After seeing the film, I believe, not only I but some visitors too will have that strange feeling of seeing friends and a particular community of artists on screen, both as themselves but also as characters. This, of course, affects the experience of the film for some of us, because we recognise Elena Narbutaitė, Gintaras Didžiapetris, Liudvikas Buklys and Algirdas Šeškus, if not always as artists, also as our neighbours, or visitors to the same exhibitions, festivals or street shops.

Since the film blurs the boundaries of diary, documentary and fiction, and the characters that you create, I am also interested in your own presence on screen. I was listening to one of your talks about your film Vivian’s Garden (2017) where you mentioned that you wanted to participate or to be involved. I wonder how you see your role or character in Denim Sky?

RN: I don’t know if I necessarily need to be seen, but I appear in it a few times, and maybe that is important. I was always trying from the beginning to be clearer about my intentions, which sounds untrue when you look at my films, because they are not very obvious.

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

JZ-B: But the opening lines for this film already set things on track when you address your children saying ‘[…] we’re starting the film this morning.’

RN: Yes, exactly, I wanted to be more explicit about what I’ve been showing over the last twenty years in films, it’s been very much my position as a body in this environment that you’re looking at. Even if you don’t see me because I’m behind the camera, you know that I’m there. But what I’m trying to do is to look at the situation which attracted me in the first place, and through the editing process, or maybe even later, figure out what it was about that situation. I tend to follow a track if I believe there is a connection between these various things, or if there is particular importance to the place, location or situation where I go and make a film. And what I want to do with the audience is to pretty much understand at the same time what it is that we’re looking at, I want this moment of comprehension.

After making Vivian’s Garden (2017) with the artists Vivian Suter and Elisabeth Wild, I learned from them a way of further collapsing the boundaries between my working life and the life in which I care for others and others care for me. Because that’s the way they live. I learned this from them, brought that back, and went to those friends, saying ‘Let’s start with this trip.’ Initially, I didn’t tell them it was going to be a film, I didn’t know myself it would be a film, but I knew I was going to do filming there. I decided to include myself more explicitly in the work, rather than just being this kind of blind spot in the middle. The children came into the picture, so I came into the picture, and particular dilemmas in my life came into the picture. I felt that this was the moment when I was ready to do that.

JZ-B: There were a few times when you mentioned a really beautiful parallel, how through mothering, painting came back to your practice, by drawing together with children. I have noticed that quite often articles describing your work note that your 16mm films are accompanied by paintings, which at first glance sounds pretty hierarchical, or simply not so right. On the other hand, thinking about Denim Sky and the dynamics between the group of friends pictured there, taking care of each other just spending time together, I thought maybe we could think of paintings accompanying film in the sense of being in company, taking care, being in parallel. Putting it as companionship or kinship between forms of expression, between the works you make. How do you see the relation between the artworks and the media in ‘Monogram’?

RN: If I think about the time I spend, I would say that filmmaking is the social side of my practice where I have to collaborate with other people; whereas painting is me alone, me and my inner life, along with references to other artists, other paintings or images, or films that come into the paintings. They are two very different ways in which I express myself, although they are both absolutely linked to me. Two sides of a coin, maybe. I definitely feel that it’s a different time that I spend: painting is a daily activity that I do usually during the week, all day if I can, and film is something that comes to my life a couple times a year as a really intense event. I work with other people and make this shooting event happen, and live in a very intense way, and then I spend several weeks or months editing, at certain moments also in conversation with another editor. They are just very different parts of my practice, but they are absolutely two sides of a coin.

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

JZ-B: It will be really interesting to read them in this way in the exhibition: as heads and tails of a coin, with signs of different rhythms and temporalities pictured on them, like the breeze and the hurricane, or day and night raves. Approaching the end of the page, I would still ask both you and Virginija about the particular (though also born out of the specific circumstances) space the show will be at. In 2020 you were selected to be a resident in the new Modern and Contemporary Art residency at the National Gallery of Art in London, and your practice has been entangled with the museum’s spaces and the historical collections they hold. Have you thought especially about taking ‘Monogram’ to an art historical setting again? Fragments, compositions and motifs from the 30th room at the National Gallery recur both in your film and paintings in a really attentive and sensible way.

RN: I really love thinking about painting and art history, and I definitely refer to it a lot in my work, sort of diving into it as well. But the Radvila Palace was obviously to do with the circumstances of the CAC being refurbished.

Virginija Januškevičiūtė (VJ): That is true of course, but there is more to the story. We knew that it wouldn’t be possible to stage the exhibition at the CAC’s usual venue, and it made sense to partner up with the National Museum of Art. You told me about the weekly tours you enjoyed so much in the different rooms of the National Gallery in London during your residency, and your painting at that time directly reflected those experiences: it made sense to enrich and complicate the museum experience in Lithuania with those reflections as well, by showing your work there. Your most recent work that we’re now showing is a bit of a departure in that sense, although of course various fragments of art history are still very present in it.

However, the film you started making in 2018 immediately felt like a part of the Lithuanian heritage. I had forgotten about it, but this spring, for instance, I found an email from Raimundas Malašauskas, written after you sent us all a viewing link to the second part of the film shot in 2019 (by that time, Raimundas had already curated your exhibition in Rotterdam that featured ‘Part One’). It’s a long and beautiful email that he wrote to everyone involved in the film, but there’s a part where he says, ‘If I were Arūnas [Gelūnas] and Lolita [Jablonskienė], I would put your film, Rosie, as a first acquisition this year “For inter-planetary support in capturing the most intimate and otherworldly portrait of a community so dear to us” they would add’.

RN: Oh, really, I completely forgot about that! And this film is also shared ownership, on many levels it is such a collaborative work.

VJ: That’s very true. It’s perhaps worth mentioning that in some ways I was also part of the process before we started thinking about the exhibition, and even before I was in ‘Part Two’. I’m friends with the people on screen, and I remember watching the looped ‘Part One’ in that exhibition in Rotterdam (at Kunstinstituut Melly, formerly Witte de With) again and again along with the people who had no connection with the film. What was so fascinating to me was to see someone capturing so well the sense of this particular set of friendships. It felt unique to be seen so clearly, first by you and then, it seemed, also by others watching your film.

At the same time, it could be anyone’s friendships. For me, the main reason to curate this exhibition in Vilnius was the huge surprise of seeing something that was so familiar to me, captured so well in an artwork that is in the end so unfamiliar, and indeed otherworldly. I see this film as something strange and unexpected, and very much full of a life of its own. There’s so much poetry in how you film and how you edit, constantly reshuffling things and finding ways to come back to the main themes that have little to do with the particular people in the film. At the same time, of course, it also feels otherworldly because of Ursula K. Le Guin’s short science-fiction story, which is alluded to in the film several times, and because the film has now settled, and the friendships on screen will continue changing in different ways to how they will change off screen.

RN: Yes, you know, you saw the shoot, and then you see the final edited version, you realise that there were fifteen million possibilities, and we chose one. Now to contradict myself, there are many ways you can go and edit, but it’s only finished when you find the only way that it could be.

One of the comments that I received from my sister-in-law after the screening at the National Gallery was that she found the film reassuring because things happen, and then the action simply moves on to other things, and this was some sort of message for her. The constancy of testing things out. There’s never a result, it’s always the next thing.

Although when I spoke to the artist Miljohn Ruperto, who is currently writing about the film, he mentioned that in the third part of the film, the things that we were doing in the first two parts ceased, we kind of dropped them. That’s interesting, because I didn’t see it that way. There was the pandemic that came in the middle of everyone’s lives, and then we carried on. I didn’t know whether that would be possible. And in fact, before we did this shoot for the final part, we had dinner in London with Elena, Gintaras, Liudvikas and Matthew Shannon, and for the first time we started talking explicitly about the film and what we’d been doing up until then. We became kind of high, really excited, and had kind of a peak before we did ‘Part Three’. I felt that we confessed to each other how we felt and where we were with the process. After that, we had to do the shoot, and the shoot is always exhausting, and has its own tensions and difficulties. Particularly going to Orkney with the Covid stuff, and all the tests, and the lockdown, and then the difficulty of shooting day and night. It was never going to be as good as it was when we were just together, without any responsibilities. At that dinner, there was a part of me that felt ‘Oh, God, if only this dinner could be on film.’ Of course, it could never have been captured. It would have been a difficult dinner, a very rehearsed thing with all the ‘try again’ and ‘try again’ and ‘try again’. This happened when we were shooting in Orkney on Liudvikas’ birthday, and we kept redoing his birthday breakfast, until it was absolutely ruined for him, he was totally exasperated. It didn’t make the cut in the end. It’s not right to pretend that everything was a good time, because it was difficult. But this ‘just having a good time’ was always somewhere around. In the film, you can see the tensions and difficulties through the children, you don’t see it so much through the adults.

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

JZ-B: And why Denim Sky?

RN: Elena came up with the title. All the parts have a long intertitle which I came up with by consulting ‘I Ching’, which is an ancient Chinese divination book from two and a half thousand years ago. I did this in 2018, just before we went away. I took the sentences which I felt were most relevant from this first consultation. The hexagram I got gave me a structure for the film: from coming together and sharing a glass of wine, through the difficulty of non-linear time in the middle, where the team horse goes astray, and then into the last part where when the wind is stirring the water and you can see the ripples.

The full title of ‘Part Three’ is: ‘The wind blows over the lake and stirs the surface of the water. Thus visible effects of the invisible show themselves’. This is when you can see something invisible become visible in a sign. You don’t see the wind, you see the ripple, but that’s a visible sign of something else, invisible wind. In the third part, I was trying to manifest things that you cannot see, trying to be explicit about things. When all three parts were finished, we needed a title for the whole thing, and because there was so much meaning in each of the intertitles, I thought that the overall title had to be something loosely associative, and not really have a specific meaning. I often discuss titles with Elena, because she’s really good at coming up with words or phrases that boil things down to the essence. Denim is the colour of the sky, but it’s also the feeling of denim as cloth. Workwear or everyday wear feeling.

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

Rosalind Nashashibi, Monogram, exhibition view, Radvila Palace Museum of Art, Vilnius, 2022. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda