In the center of the green hall, I find a peculiar being. Its surface is glossy and rough, unpolished. It looks both stationary and flexible. I am talking about a curved being, which isn’t always one whole, as I can clearly distinguish various connection points, bolts and screws. During the summer of 2022, I regularly guard it. And almost every day, Objekt by Jass Kaselaan reminds me of The Machine.lau

I have actually never seen The Machine – only read about it through the words of E.M. Forster. The science fiction short story, written in 1965, follows Vashti and Kuno, mother and son who live in isolated cells beneath the earth’s surface. From their own pod, that could be described as a bee-cell, they are supposed to have access to all the basics a human life needs. Frankly, I am not sure how much is going on inside of a sculpture like Kasselaan’s, and whether it could provide me with a comparable service like The Machine claims to possess. Yet this story picks up on a few elements inherent to the medium of sculpture, remarkably well brought together in the exhibition Tuur Skulptuur.

The show’s starting point doesn’t seem to be any kind of theories written by Foucault, Sontag, or Plato. Thinking about the philosopher’s cave, The Machine could easily be experienced as a dystopian, futuristic and solitary version of one. Things are still happening: ideas and theories are vividly explored by the people underground. But they are second hand, as representations without any primary experience. They feel colder, much like those shadows casted on a wall. Tuur Skulptuur on the other hand steps outside the cave: I feel a steering interest in material and direct interactions with it. Think about the warmth of wood and layerdness of paper maché. The exhibition works in the opposite direction to the way I often encounter today: it starts from the material. This may be a liberation after the glimpse of isolation we all experienced the last years, where representations and images were our most tangible meetings with the outside. As a guard, I move through the hall to turn on various kinetic sculptures and spots. As an artist, I regularly roam the hall with the sole intention to see, sense and rediscover. Although I’m trained to look, I am surprised to ask myself whether some works were added later. Because how could I have overlooked that creme-white, chestnut-peel-like sculpture of Sasha Tishkov? I guess I forget the surplus texture: the one created between the works, how they internally manage to make another actively appear, rest and blossom.

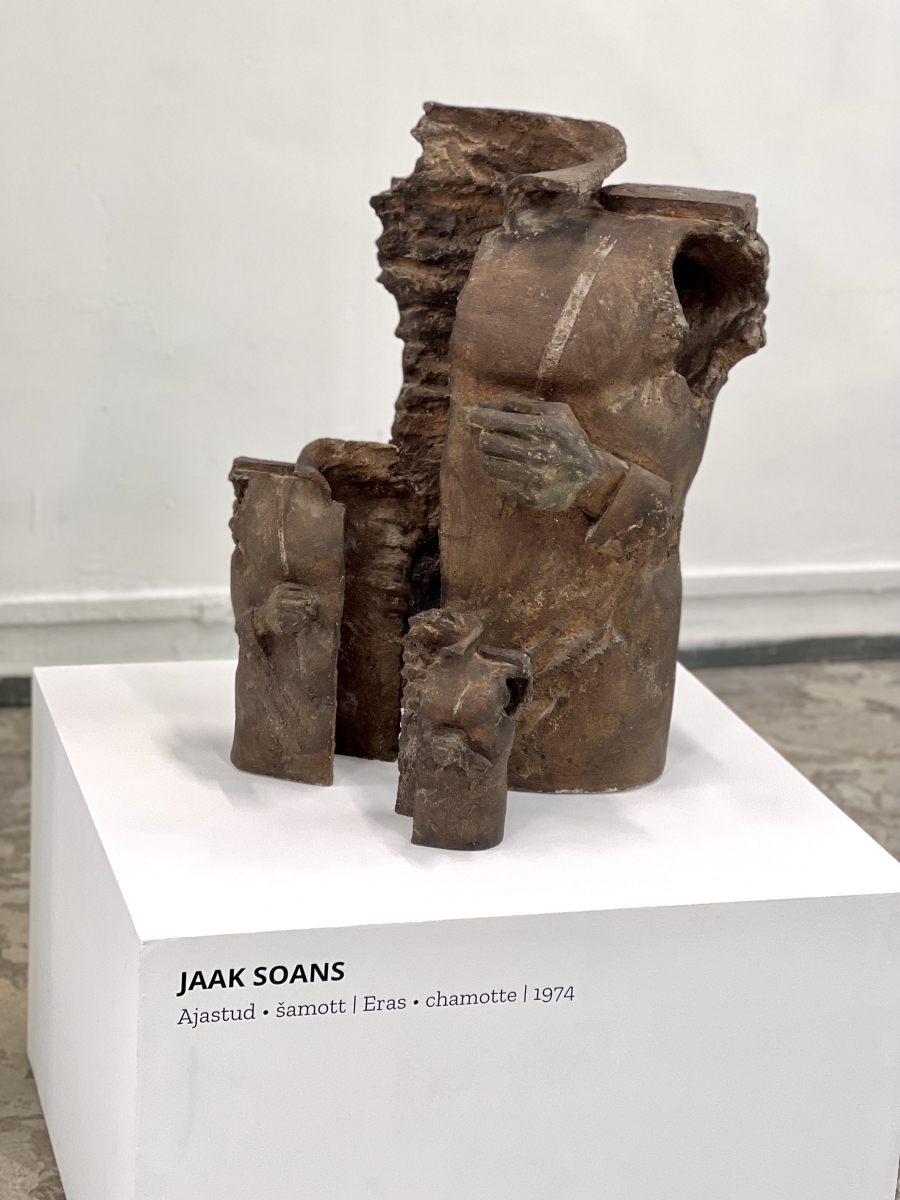

This practice doesn’t mean to exclude virtual experiments and questions about materiality in the broad sense of the word. (Quite the opposite, as I am probably already hypnotized by the enchanting soundscape of Taavi Tulev, softly assisting me to hop through the works). The exhibition chooses for a pluralistic approach, providing us an overview of contemporary sculptural practices. Thereby, they do not constrain themself to solely new, experimental proposals, to again push the boundaries of the medium. The exhibition takes a step back towards the start of contemporary sculpture. An interesting point, because could I even paint a picture of the field’s future without its starting questions? Should sculpture learn from its past or not be contaminated by it, in order to provide an alternative future? As a young artist, working in the field of ‘free arts’ (a literal translation of my degree), I found many difficulties in starting to experiment without any handles on which materials can be used. After all, wasn’t The Machine created by humans, on the surface, after a full history of understanding of their surroundings and needs accordingly? Tuur Skulptuur gives me a primary example of the multitude and diverse sculptural approaches in Estonia over a span of 60 years. I am catapulted from wood to glass fiber, from classical casting methods to ready mades, from the body up until the bone to the ventilation tubes of buildings. Some of these juxtapositions taste spicy. But in many cases, the new commissioned works with earlier pieces make sense. I notice Jüri Ojaver and Jaak Soans practices echo in Johannes Luik’s choice of material, and Nora Raba, as well as Anu Poder, whisper to Eva Mustonen. The long corner table combining various portraits balances its wide stare towards the three bodies of Anna Trell. In the end, the best writers are good readers, the roots of old trees break through fresh asphalt roads and there is no forward if there is nothing to depart from.

Most of all, curators Bianka Soe and Mara Ljutjuk acted as surface dwellers. Although the online Urban Dictionary does not do justice to the concept, I am talking about Forster’s name for the curious and rebellious souls that dare to leave The Machine and reinvent life on the surface, surrounded by the material that

was left over, on their own terms. It is a bold move (one of the aspects Ojaver recently told me during his visit that is essential to become a great artist!) as they manage to plant about a hundred works in one open hall. Quite a challenge in times where everything becomes installation and thus glues the quality of space to each artwork. This implied space every sculpture has today almost feels like playing it safe. Instead, Ljutjuk and Soe dare to throw the visitor in a timeline of not only the Estonian sculptural field, surprisingly well positioned as a hive structure itself, but also on their own road of serendipity. This tour through sculpture does not start in the exhibition hall. The show is the result of a process of roaming through the country, dwelling in artists’ studios with a deep, continuous interest in practice, to discover treasures that carry the medium.

To understand an oeuvre and artistic creation in its purest practice isn’t a given in all curatorial approaches. In some cases, art theorists are separated from where practice happens, as many art and cultural academic masters are part of a humanities campus rather than the academy. Artists are skeptical of cultural studies’ tendencies as they might instrumentalize them, and some art historians have never set foot yet in an artist-run space. The Estonian Academy of Art (EKA) in Tallinn is an exciting example where theorists and curatorial students are located right next to the graphic and sculpture studios, the metal and spray painting labs. This allows art workers to grow right next to the process of making, and thus to understand the most important aspect of sculpture: the continuous exchange with space and substance, and thinking through material.

Behind 2 heavy green doors, there are 8 pillars, 4 times 10 windows, 2 times 6 windows and 2 times 2 windows. The space in between is absorbed with sculptures, of different ages, with various questions. To move through them asks for flexibility, presence, and a deep longing to dwell. It is not hard to be ‘captured at first sight’, as the many people moving through the building sneak their heads with wonder through the doors. But it is touring around that brings out the countless connections these works contain, continuously echoing one-another.

Tour Sculpture

A tour in local sculpture-land

Open: June 2–August 21, 2022

Location: Green Hall at Telliskivi Creative City, Tallinn

Exhibition curators: Mara Ljutjuk and Bianka Soe

Artists: Elo Liiv, Art Allmägi, Edith Karlson, Jass Kaselaan, Seaküla Simson, Mati Karmin, Eike Eplik, Tiiu Kirsipuu, Jüri Ojaver, Terje Ojaver, Kaarel Kurismaa, Heleliis Hõim, Aili Vahtrapuu, Johannes Luik, Jevgeni Zolotko, Per William Petersen, Kris Lemsalu, Mare Mikof, Vergo Vernik, Ahti Seppet, Kirke Kangro, Sofia Fatahhova, Loora Kaubi, Aime Kuulbusch, Villu Jaanisoo, Berit Talpsepp-Jaanisoo, Uku Sepsivart, Lauri, Eneken Maripuu, Margus Kadarik, Leena Kuutma, Mari-Liis Tammi, Maigi Magnus, René Reinumäe, Anna Mari Liivrand, Kiwa, Gea Sibola-Hansen, Flo Kasearu, Eva Mustonen, Kelly Alloha, Ivan Zubaka, Ekke Väli, Jaak Soans, Hille Palm, Ellen Kolk, Sasha Tishkov, Anna Trell, Hannes Starkopf, Ülo Õun, Peeter Mudist, Edgar Viies, Anu Põder, Nora Raba, Endel Taniloo, Riho Kuld, Irina Rätsep, Anne Paberit, Elmar Rebane, Georgi Markelov, Erna Viitol, Signe Mölder.

Laura De Jaeger (1995) is a Belgian artist and cultural theorist living and working in Estonia. Her art practice deals with the notion of in-between, by gathering, molding, measuring, and rephrasing local histories and quotidian practices. She writes about contemporary art exhibitions from an experience-based approach, focussing on associative potential and material thinking.

Photography: Bianka Soe