Kaspars and I sat down for this conversation the day after the opening of his solo exhibition ‘The Old Man Goes Home’ at Editorial in Vilnius. The exhibition features an entirely new series of paintings, all in one uniform size and with a striking colour scheme, each painting typically introducing a figure against a particularly moody background. The figures themselves are somewhat disengaged, but each one has a very distinctive appearance, or even a mode of being: there’s a Lynchian rabbit, a devil, a mouse, a fisherman. One could describe them as a dream sequence, or an assortment of video game avatars confined to their little homes in virtual landscapes so that the gamer can always find them.

Kaspars describes the key protagonist in the exhibition as someone who is rather timeless, someone who could be living in the 17th, 19th and 21st centuries all at once. Despite knowing Kaspars for years, I could not help thinking a similar thing about him too. At times I felt I was talking to the kind of person early German ethnographers interviewed on their first trips to the Baltics, when they were trying to collect information about the people’s world-view, so that they could later connect it to something that they already knew. I imagine they were similarly drawn into rather wild and potentially never-ending narratives. As a result, I also found myself asking some very strange questions. You will notice that when he says, for instance, that he was ‘wrestling with the fireman’, it is not very clear if he means the process of painting or wrestling with its actual, albeit imaginary (one would assume), subject. Despite all this slight unhinged-ness and so much referencing to the formative years of being a teenager, Kaspars has been one of the key pillars of the Latvian art scene for many years, and continues to be one of a number of constantly changing and evolving roles.

The interview also contains an unexpected announcement of a Latvian 1980s avant-garde artist group’s exhibition next year at the Radvila Palace. I hope you‘ll find the interview interesting enough to read until you reach that part.

Kaspars Groševs, The Old Man Goes Home, 2022. Exhibition view at Editorial

Virginija Januškevičiūtė: You gave us a tour of your exhibition yesterday: it was a really fantastic little tour, where you explained how everything kind of started with this one painting of an old man. But I haven’t yet read the text that you wrote for the exhibition.

Kaspars Groševs: The text is a story, or a bit like a tale, about an old man who goes home. And then it just describes some things that might be known about the old man. It’s not even that important where he is coming from or where he is going. Maybe the process is more important, that he’s walking. As he walks he sees all those scenes, the scenes that are supposedly happening as he goes home; these are all the other paintings in the exhibition. He kind of doesn’t pay attention to those scenes, though. He knows everything, he knows nothing. He’s bringing this sort of maybe like … even, some, like, old age with him. And then there is a kind of a small twist at the very end where it is revealed that maybe this old man is a god.

VJ: Aha!

KG: I mean, the title came very spontaneously. I just thought at first that it’s a very funny title. I was looking at the painting, and yes, it was basically showing an old man going home.

VJ: How did you come to make it in the first place? It’s so different from your other work.

KG: I know! I was experimenting with painting, with acrylics, mixing acrylics with spray paint, then different acrylics … I was experimenting, and then it just came out as a stroke. Very accidentally, because I was working on something completely different. I was working on this series of paintings that are more like portraits, of familiar faces, but not really familiar faces. I was focused on that. And so this came very accidentally. At first I didn’t know what to do with it, because it did not go together with everything else at all. But then I really started to think that there is a wider landscape than just this one image. That there’s more where it came from. It grew, and I feel that I will also continue with it.

VJ: With the walk.

KG: With the world, and also the way it’s made. First, it starts as an experiment with paint, and then I’m trying to find some strange colours, or just some shapes. Some sort of, yes, directions. And then it grows and becomes more detailed. They don’t start as a narrative. They start very improvised: I’m doing it and trying to guess the next move.

VJ: And when you say that it came out in one stroke, do you mean the old man as a character?

KG: Yes. At first I tried to paint some sort of figure in an empty colourful space. But then it became blurry, just a smudge. And then this smudge grew into an old man. First it was completely like just a spirit moving through a landscape. It wasn’t even a landscape at that point.

VJ: I noticed that if you look at the shadow of the old man, you see that there is a shadow under his feet, too, as if he’s floating above the ground.

KG: Yes, it’s true. I wouldn’t say that it’s a deliberate move, but it makes sense. Because he might be a god. I mean, this god thing … In Latvia you also call your dad an old man, or just use it to address your friend. So one connotation was with a dad, the head of a family, walking home super-tired after work. The title of this painting with the old man is Lopiņš, which means ‘barn animal’. There’s this little saying ‘The night is coming soon, the barn animal is going home.’ But then there are also Latvian folk tales where sometimes there is this old man walking without a home, without belongings. He stops at a house and asks to come inside for some food. If someone feeds him and treats him well, he repays them. If someone treats him badly, they get sort of consequences. Because it turns out that this old man is a god dressed as an old man, like a bum.

Kaspars Groševs, The Old Man Goes Home, 2022. Exhibition view at Editorial

VJ: So the other paintings, are they what he sees as he walks past those scenes, like the homes of those people in the fairy tales, or are you saying that he is so indifferent that in fact he doesn’t see much at all, nothing that we see?

KG: Yes, it’s very likely that he’s not paying much attention. I also just remembered that twenty years ago there was this homeless guy always next to the Freedom Monument in Riga. Everyone called him the overlord of the world, ‘pasaules valdnieks’. Not really the king, but definitely the ruler. He was always walking around and talking nonsense. Sometimes he’d say something funny, too. For instance, we were kids, teenagers, and my friend was smoking, and he said, ‘If you continue smoking, your penis will drop off!’ Things like that. But yes, there is something about this old man who could be anyone.

VJ: Do you follow other painters’ work?

KG: My friend Eriks Apalais says he feels that the title The Old Man Goes Home is about old traditions ‘going home’, especially perhaps in a Latvian context. Some new blood comes in, the old habits go home. Even in the context of painting alone, those old traditions, a very misunderstood way of painting, not misunderstood, but confused. You know, it’s kind of figurative, sometimes trying to be experimental, or modernist, but always half-baked. Strange, mostly strange. That’s most of Latvian painting.

But I started painting again because I realised I like looking at paintings. I really enjoy spatial works, but I’m not so good with space, so at some point I just gave up on the third dimension. I started making works on paper, then drawing on canvas: at first it was basically drawing with paint, and only later became more painterly. But I also studied painting for a whole eight years, and I really enjoy painting, especially this series. It was a real pleasure, I could do it all day. Which is strange, because I don’t usually spend much time on my artworks. I can’t imagine going further than this, like spending several weeks or even several months on a painting; that’s probably something I will never do.

After the Art Academy, I tried to forget about painting. Now I have rather semi-successfully forgotten a lot about it, so a lot of the time I just improvise with my limited skills. My skills are more related to drawing, they are all about lines, and how you can use a line in so many different ways. It may seem strange, but for me the line has the biggest potential. And then colour: it is a great pleasure to play with different combinations. Sometimes I don’t even see some parts of a painting. I’m a little bit colour blind.

VJ: Really? What do you see then?

KG: I just don’t see them. There is this painting with a boat and a yellow raincoat, fishing, and underneath there is this pink underlayer. I painted on it with some kind of green-blue, bluish green, and some parts are the same kind of intensity in terms of how bright they are. For me. At the time I see that I am painting, I can see the strokes; but I return to the painting later, and there is this part where I can’t really see the strokes there. I see this weird pinkish texture.

VJ: I’ve already started imagining that you see a hole in the painting, almost like that cave orifice in this painting of yours with the demon.

KG: This one’s Freiherr’s Cave. Freiherr, the German baron. It comes from another Latvian tale about a rich German who has some servants. The stableman has to take him to the forest every night, where he disappears behind the bushes, and he comes back in the morning drunk. After several nights he gets curious, what’s happening there? He finds out that there is a demon party with German barons boiling in these big tubs, there’s drinking and orgies, or something like that. So it came almost like a joke, to paint this cave, guarded by a demon. I don’t know if it has a deeper … deeper story. It’s a lot about how these tales came to be four to five centuries ago, under German oppression. There are many tales about these barons, depicting them as demons, even showing that they are collaborating with demons in contrast to these proper German Christians who came to Latvia to bring Christianity. Or maybe I just listened to too much black metal at some point. I used to love tales as a kid though, those books of tales from Africa, and so on.

VJ: They weren’t illustrated, were they?

KG: Sometimes they were, in black and white. When you’re a kid you don’t need colours. Black and white is enough, and if there’s something you can barely recognise, your imagination works.

VJ: Especially if you’re colour blind …

KG: Yes! But I only realised I was colour blind when I was trying to get into an art high school. I had to do some tests, and the eye doctor thought people would laugh at me if I went to an art school. She said, ‘You won’t be able to do anything there.’ I panicked, but of course everything turned out fine. What I didn’t know at the time is that when I was trying to get into the art school the school’s director was super-colour blind. I wish I had known that when I went to the doctor. The director, Edgars Vērpe, was there for a short time, but he’s a good guy, a painter. He paints fish.

At some point later I also gave up a little on colour matching. I still unintentionally have some inner colour matching mechanism. But sometimes I try mixing colours that shouldn’t really go together, so that it’s off, or a little too wild. I also use spray paint, which in the tradition of painting is perhaps most associated with someone who makes a painting on a street in under five minutes. These are always super-decorative, Malibu palm trees, mountains, and the like. They use spray paint and stencils so that it’s faster. I figured I can learn a lot from them. But of course their work ends up looking like five million other paintings of Malibu.

VJ: Do you always have an idea for your next painting, or do they come to you one by one?

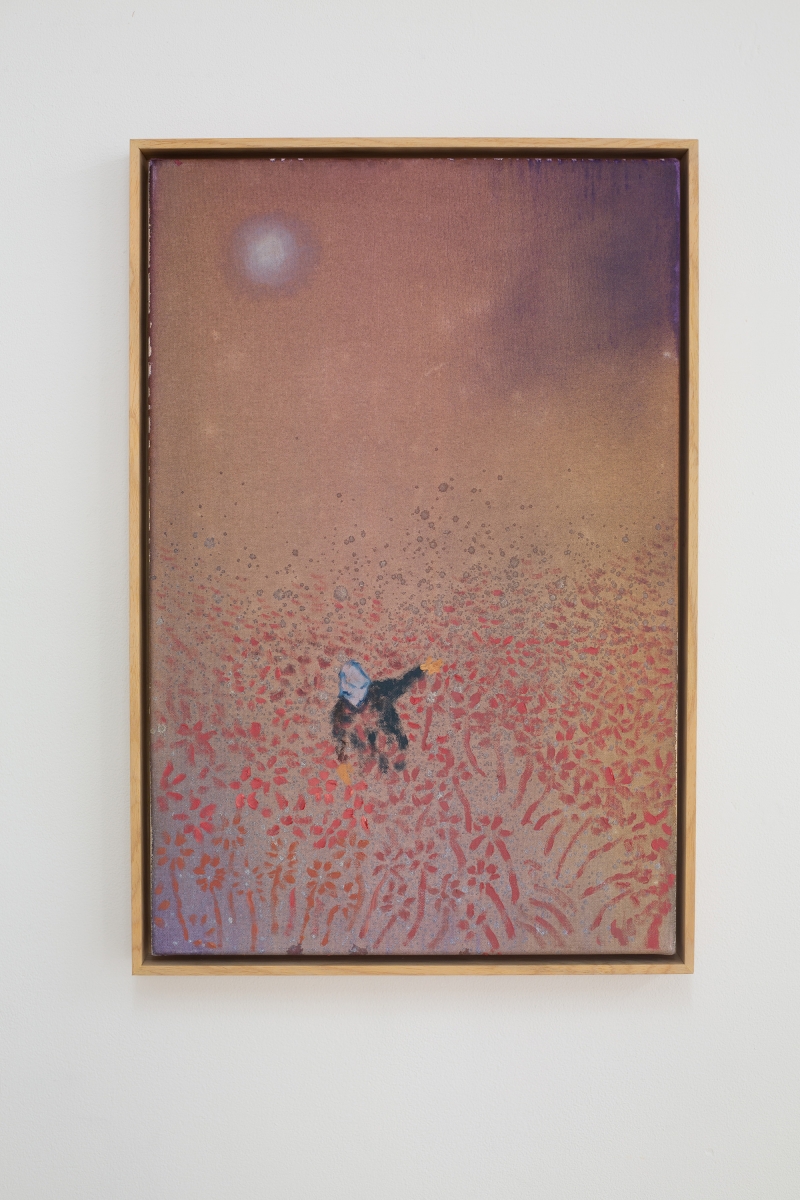

KG: I start with the background, with the colours, then I try to imagine what more could be there. The first one in the room, with this woman going through a field and this vague sun, started with the colour and the spray paint. It looked like summer dust, or maybe smoggy air, or smoky air, some kind of cloudy conditions. It could be the moment before thunder, or the moment after an explosion. The title of this painting, May (Theresa), is more like a joke.

Kaspars Groševs, May (Theresa), 2022. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 40 x 60 cm

VJ: What’s the joke?

KG: I read an interview somewhere with her where the journalist asked her what her wildest memory was of getting into trouble as a child, and she said it was running through a cornfield. She was so distanced from the general public that for her it was something crazy. But for most people, you know, you ask them what the craziest thing is they did as a kid, and the further you go into the countryside the wilder the stories you hear. I heard a story a few weeks ago that someone almost choked as a kid, because he was trying to show how many socks he could put in his mouth. He put in seven, started to choke, and his friend pulled out them out and basically saved him. When I heard the story, his mum was with us, and she was shaking her head and saying, ‘I wish I didn’t know that.’

VJ: Oh my God.

KG: So the Theresa May story for me is about how distant she is as a politician, but you can also see that in other leaders of bigger countries. Even if people are more supportive of Ukraine, the big politicians are always calculating. It’s not a political work at all, but this is maybe something you can sense in it. The atmosphere is very strong, though. Maybe it’s a person in a post-apocalyptic field.

VJ: Tell me more about the series you said you are making of your friends.

KG: It started as a project last year when I had this kiosk in Riga called Lagoon. For two months every month an artist made a work in this kiosk, although it was tiny, four by five metres. Every Monday an artist added something, and then another artist added to the previous things, and then another one came. Every Monday we also had some DJs or musicians, performances, different kinds of things. It grew into a bigger project that we are opening in a month at the Cēsis Art Festival in Latvia.

Along the way, I also started painting these … faces? I wouldn’t say they are all my friends, sometimes they are a bit anonymous, like someone I knew but I’m not sure who it was. Or sometimes I have a person in mind whom I want to paint but I never reference photographs, I just paint from memory. When I show these images to friends, sometimes they don’t recognise these people unless I tell them who it is. But it doesn’t matter, in any case it’s more about the painting, the brushstrokes. Sometimes the paint is really thick, these paintings are a bit more physical, some of the faces have these rough textures, they have so much paint on them that they look a bit destroyed. That series is called Someone Who Isn’t Me. It’s a term from internet drug forums where people use this abbreviation, SWIM, Someone Who Isn’t Me, to talk about their experience on drugs, or to ask questions.

In this series there is one figure that is kind of like a corpse. I have this memory from an early 2000s underground festival in Madona in Latvia, where a punk died. Some locals got into a fight with him and they threw him into a lake. Around the time when this happened, we were teenagers, my friend’s dad arranged for us to meet this underground artist who was using spray paint to make very cheesy graffiti on paper. I tried to find his work later and I saw it’s quite horrible, it’s actually just bad painting. But back then I thought it was amazing. Bright colours, very punk, very DIY. We felt like we met this artist who’s making stuff. He was a punk, his pants barely holding on his legs, lots of piercing and everything. He told us he used to have a punk band, but one of the band members committed suicide and another drowned. Years later I connected these two stories. I don’t know. I very often make connections in my mind between things, it’s almost like an early stage of schizophrenia, which is called apophenia, when you start seeing connections in things that are not connected.

VJ: You think he was in a band with the same person who drowned?

KG: I think there might be a connection. My friend later wrote an essay about that person in the lake and read it at a festival, it kind of stuck in my mind. Similarly, some of the paintings at Editorial have references to my personal stories.

VJ: What about the one with a man putting out a forest fire?

KG: That was very random. I made this very fiery painting with a forest, and I was struggling with the fireman; in the end he became this strange character, almost in pyjamas. Also, you know, if with an old man it could be a scene from any century, it could be the 17th century, the 19th, or it could be happening now, the fireman seems more recent.

VJ: You often seem to find things to do or paint that are potentially an endless series. ‘What does God see?’ or ‘Who I can paint?’ Your kiosk could also go on and on for ages. And you still make music, don’t you?

KG: Now it’s mainly live improvised concerts. I use concerts as rehearsals. But yes, I like continuing these threads of thought, or rather vague ideas of how things could move ahead. Along the way, it becomes more detailed and more saturated, and more and more interpretations appear. With music, when I make a track or do something, the next time I always continue from where I left off. I stop at some point, and then I take it from there when I return.

VJ: I just can’t stop thinking about the boy who pulled all those socks out of his mouth. I get a sense from you that there’s a strong connection between him not choking and this seriality of work, almost like there’s a necessity to it.

KG: In Covid times there were times when I struggled to do something regularly, even to draw. I used to draw so much, and at some point I just stopped. I didn’t want to, or I didn’t have the energy. I like it now that things are open again and I get plenty of ideas from conversations or by going to places. Some things some things stick in the memory and then you try to capture it somehow.

It’s similar in other things for me. When we opened the 427 project space in Riga in 2014, the idea at the beginning was very different with regard to what it could be. It grew into itself gradually, it took shape. Now there are still a lot of options for what we can do, and we can still change the direction if we want to, but over time things grow together, and there are connections between them, at least in my mind, because I’ve seen all the shows. I don’t know if a regular visitor sees these synchronicities in the programme.

VJ: They say all exhibitions are made for an imaginary viewer anyway.

KG: That’s all we have in Latvia. And an imaginary reviewer. We don’t have any real ones. Art-wise in Latvia now there are a lot of things happening, really a lot: new project spaces, smaller venues, temporary locations. But there’s barely anyone who writes reviews. For a while I was trying to fill that position, but I don’t really want to. I wrote a couple of reviews, but it’s not my jam. There aren’t enough curators either, but that might change with the curatorial MA programme at the Art Academy: there are more people now who are considering it as a profession, or one of the things that they do in life, so we’ll see.

Kaspars Groševs, The Old Man Goes Home, 2022. Exhibition view at Editorial

VJ: What’s the next thing you’ll paint now?

KG: I’ll probably continue this. But in Cēsis the space is huge, so I might be going for larger formats, we’ll see. I’m still learning how to make paintings. But so it will not be just portraits. The exhibition that I’m doing there together with Evita Vasiljeva references this one utopian drawing by Hardijs Lediņš, the Latvian avant-garde legend. He was part of the avant-garde group NSRD from the 1980s, quite influential for me and for Evita, which was also a community. They supported each other, especially in the 1980s, in Soviet times. What they did was necessarily what everyone wanted. The avant-garde experiments weren’t really accepted. My interest in this grew into an exploration of local art communities and how they are often connected to certain places.

The basis of the NSRD was two people, Hardijs Lediņš and Juris Boiko. Both died quite young. I think they both studied architecture, or maybe Boiko studied philosophy. They started making music together, then some zines with drawings and experimental text, like the poem, I don’t know what to call it, a text called ‘ZUN ZUN’ from the early 1980s, very Dada-ist, where they play around with how the language sounds. Maija Kurševa recently published a facsimile of it. It was always a bit silly with them: lots of humour and a sort of lightness. They did performances, too. For instance, the performance of going from central Riga to Bolderāja, a remote suburb. They would always walk along the railway, starting in the middle of the day or in the middle of the night, so that they would have the change of light. I imagine this walk could last three, four or five hours. Along the way, they did some performances, happenings, musical things. It attracted a lot of people who were into creative stuff at the time: musicians, artists and critics. At the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s they also did some things in Germany, but they slowly dispersed in the 1990s. But in the 1980s they made so many amazing music records, ranging from completely experimental ambient music to almost pop songs. Very strange ones, the kind that the weirdly dressed kids in art schools listen to. So their biggest influence on me is their music. But over time you find out that they did performances and video art. Their show is supposed to be in Vilnius at the end of next year or the beginning of 2024. The LCCA is curating it and it should open at the Radvila Palace.

VJ: Oh wow! I’ll look forward to it. It sounds like the Riga art scene owes a lot to these people walking together.

KG: One of the ideas for my kiosk was that in the 1980s they had Bolderāja, these suburbs, and now we have a bookshop and a bar with the same name. It’s often where you meet different artists from different generations, so now going to Bolderāja means something completely different. It was one of the connecting points for the choice of artists at the kiosk: they all met at Bolderāja at some point.

VJ: Thank you for the conversation and your generosity, Kaspars, I’m glad we found a chance to talk. I learned a lot!

Photo reportage from the exhibition ‘The Old Man Goes Home’ by Kaspars Groševs at Editorial

Kaspars Groševs, Lopiņš, 2022. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 40 x 60 cm