Compared to ‘real’ space, in virtual space the socio-epistemic structures, by means of which the meaning of the terms ‘self’ and ‘body’ are produced, operate differently.[1]

I cannot think of a better place to discuss the media and the ideas which roam over them than a review for a media art festival. Frankly, the challenge is precisely the question of the will of the media (as in writing, contemporary art language, and digital and personal time). The omnipotent soundtrack to this review is Okay Kaya’s Overstimulated (2020): ‘Anything could happen at any given time, no wonder why I’m overstimulated […] Are you awake? (Hey).’[2] The media is everywhere, is everything, always. That does not explain anything yet, although it provides a solid basis for many talented theoretical opuses. Hence, it was in the white light of the dystopian spring of 2020 that I studied them with the thoroughness of Talmudic interpreters: in a hypothetical zoom conference, Marshall McLuhan, Steve Dixon, Philip Auslander, Jon Stratton, Allucquére Rosanne-Stone, Jean Baudrillard, referred to by Merleau-Ponty, Dorothea Von Hantelmann, Peggy Phelan, James Loxley, Erika Fischer-Lichte, Judith Butler, Jacques Derrida, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Roselee Goldberg, Stelarc, W.J.T. Mitchell, Hans Thies Lehmann, and others, participated at different intensities.

The lightning speed sparked an interest in the causes of things that could not be revealed by the sequence or a chain of things. No one asked any more what came first, the chicken or the egg. Suddenly, it began to look las if the egg had invented the hen to have more eggs.[3] In the background noise, I recognise an echo of McLuhan’s reproach. The secret of the (un)success of this writer is the lightning-fast mythology[4] of his thought. Having harnessed the wind of the ‘luminiferous ether’,[5] the 20th-century media prophecies distorted the space around us with such willpower that we all found ourselves in one relentless interferometer of modern media: respond as you may. Whereas, if the instantaneous media stimuli only result in a mass narcissistic narcosis, wake up, Lazarus! Here: the global pandemic, the worldwide radicalisation of politics, increasingly original conspiracy theories (e.g. I have recently heard from a distant acquaintance in Romania that the media-produced intimidation of Covid-19 suppresses the natural vibrations in each of us, thus making us more vulnerable to the threats posed by the virus), the systemic exploitation of species and social minorities (LGBT in Poland, #BLM in the United States, the ‘blind-spots’ of feminism in private and professional life, and the incomprehensible treatment of animals), here and there, the threat of a nuclear catastrophe, the incessant depletion of natural and inner resources, as well as … this month’s invoices from the communications providers; we may recommend you rely on the 21 ‘commandments’[6] of Yuval Noah Harrari, but we cannot guarantee you anything in particular. Except, perhaps, that the almighty media will easily secure a role in these processes, and/or become their critical-creative reflections. Having considered such circumstances, self-isolation (isolation: [self]exclusion, [self]seclusion) no longer seems to be such an unattractive tactic of being … In fact, I am myself a positive example of self-isolation in a hostile media, since growing up in the city of Šiauliai, I not only separated from it, but became a ‘licensed medium’, capable of manipulating holistic contemporary art autonomies and the complicated inwardnesses of artworks, and taming the noose of abstract words, decidedly. With regard to the mass media, it is a small yet critical oasis of being. Giving it a second thought, belonging to a homogenous medium, has never been a priority for my tribe; however, having relied on the ‘ENTER’ (and not ‘ESC’) attitude in my adolescence, the return to the media art celebration in Šiauliai in the last days of the pandemic summer also led to a more intimate relationship with the works presented at the festival, and the myths they explored.

Nothing follows from a sequence, except for change.[7]

Nothing follows from a sequence, except for change.[7]

Fait accompli: on 21 August this year, the opening ceremony of the ENTER media art festival took place in Šiauliai Art Gallery (Šiaulių Dailės galerija), for the 18th time since the festival’s beginning in early 2000.

I consciously keep using terms such as ‘festivities’, since only on rare occasions would you be able to adhere to such a candid and purposeful celebration of creativity, which I generally like to refer to as a wholesome and complex production of being (ref: de – Produktion von präsens). Curating and promoting emerging contemporary artists, ‘directing’ inconvenient cathartic experiences, and offering the post-industrial, ageing, yet constantly being ‘rejuvenated’ by the ‘concrete-toxin’ injections into the whole body of the city of Šiauliai, Šiauliai Art Gallery is sticking to its uninterrupted mission, and offering alternative ‘scenarios of survival’ to its audiences. It is only through the production of such a different presence that an institution becomes a certain oasis of contemporary culture in the city (occasionally and mostly habitually referred to as ‘Utopia’ by some of the townsfolk, although experiencing little or no loss due to this habit). Functioning as a scenario of survival in a particular place, our oasis must function flawlessly and be useful in practice, always on time, engaging only in effective rhetoric, representing the most audience-exciting and the best comprehended (or most convincingly explained) art-processes and images, in such a way educating, (self)expanding, and including new members in the media. In other words, it must function without allowing any ‘reality gap’, through which anything less than ART could sneak into the oasis. Naturally, so as to conceive and implement such a spacial model, certain key principles have to be set up and followed passionately: professionalism, now-ness (try to imagine how time functions in a theatre production), openness (do not become self-relevant), mediality (we are producing grounds for relations), community (we are the medium space of the city and its art), novelty (Nothing follows from a sequence, except for change), sincere indulgence (There is not enough RAM/ In the known universe to complete/ The task you have requested./Accept? Rejoice?[8]). After years and years of relying on such ‘strategic’ principles, someone from the audience finds herself at the opening night of a media festival, organised for the 18th time, but as relevant in the present.

Let’s inspect the innovation and look bravely into the virtualised future, together with the artists.[9]

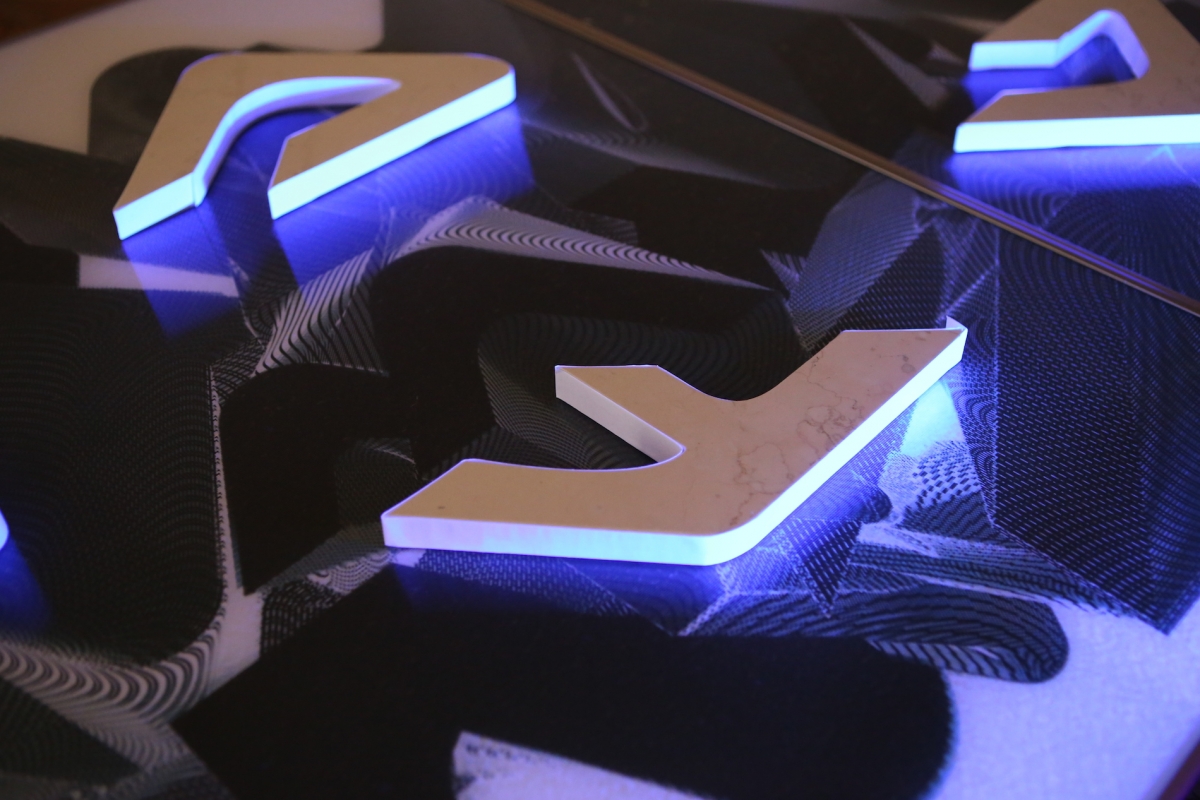

This invitation for the artists and audiences to the ENTER 2020 festival quoted above was manifested in three contemporary art shows that filled the gallery space on the opening day: INSPECTRATE (curator Virginijus Kinčinaitis), the collection from the biennial Travelling Letters 19 (Keliaujačios Raidės 19), UROBORAS: Collection (curator Marius Žalneravičius), as well as the Vilnius Academy of Art (VAA) FAMM (photography and media-art department) this year’s selection of the youngest artists’ works: >iltys / hopes & slopes (curator Vytautas Michelkevičius). The programme of the opening night was qualitatively supplemented by performances and temporary installations/events designed for other spaces in the city (the inner yard of the Šiauliai Drama Theatre hosted an open-air screening of the VAA’s ‘hopes & slopes’ video works, while the live performance and multi-media project presentation, accordingly, took place in the public square in front of the gallery and the chamber exhibition space of the Šiauliai section of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union (NGO). Although each of the three exhibitions in the festival had its own story, curator and conception, in the common ‘ENTER 18’ context, I would describe most of the artworks presented in them in terms of a certain eloquent and fluid transition (or even an intentional ‘promenade’) through the different states of the same narrative, conceptual problem, artistic or media format, and the ideological content in general, appealing to the diverse imagery and visuality of the ‘promenade’. Without too much anticipation, perhaps the ‘pandemic of digitalisation’, so inherent to the year 2020, had something to do with the artists creating such ‘looping’ experiences with regard to the different media and their message? Starting with the animated chimpanzee and robot in two vertical LED-screens, knitting their respectively digital alpha (α the beginning) and omega (Ω the end), which never make contact due to their digital nature, and the format of the two separate screens; towards: the Pinterest galleries of fundamental human feelings and emotions (i.e. fear, anger, anxiety, etc.), printed on certain contemporary ‘parchment rolls’ that stretch down from the high walls of the exhibition space, unwrapping thousands of strange faces, distorted by the same universal emotion; following: the artworks simultaneously present in different media, or operating them in their production phase, i.e. the typographical ‘knygynas’ (the Lithuanian for ‘bookshop’) which highlights such a material difference between the physical signboard of a no-longer-existing bookshop, inscribed with organic rust, and the digital ‘research’ into the same text (Knygynas) that was performed as an animated typography video work, and became a certain replica or a double of the original body of the sculptural bookshop plate; following: the bust of a human-woman and an unspecified plaster hero from Antiquity, swapping and glimmering from yet another screen (video-installation), placed in a distant showcase window of the gallery’s public reading room on the first floor of the building; or: the performance work Red Ponds (in Lithuanian Raudonos Balos) by Simona Martinkutė, enacted both outside the gallery and in one of the festival’s exhibitions, where it ‘echoed’ the live performance, in a video piece that captured the single conceptual act of washing off one’s hands a red, blood-like substance under running water, as well as the material red ‘pond’ of plastic installed alongside the video and inscribed with a tag from Šiauliai Elnias (the Lithuanian for ‘deer’) leather factory. Witnessing Martinkutė’s performance, I was once again pervaded by a certain ‘nostalgia’ for my teenage years in Šiauliai, when, with Japanese chopsticks (bought, necessarily, somewhere like Amsterdam, during the school summer vacation) piercing our hairdos, a group of aspiring young ladies, carrying Kurt Vonnegut novels in their hardbags, we used to go to exhibition openings at Šiauliai Art Gallery … In the presence, a group of young ladies (the performance crew), adorned in black trench-coats, white mid-rise stockings, and (surprisingly matching) medical face masks, each poured ten litres of red paint, in a particularly ritualistic manner, out of aluminium buckets on to the pavement, and then at once started collecting it back into the buckets, with ever-increasing fervour, and in the rhythm of the electronic music, finally spreading themselves around the audience in a performative red footprint.

Probably the least ‘formalist’ example of an artistic game in different shapes and media of the same problem or issue (already discussed briefly in the text) could be the minimalist paintworks that contained only a descriptive phrase in black type on a white background (remember the ‘textbook’ artwork One and Three Chairs by the conceptualist Joseph Koshut): Silhouette portrait of a lonely unknown man sitting on a bench, watching the dark sky sliding above him – the sun creates a stretch of light between the clouds, said one of the paintings, which made me fall in love with it just after entering the show. In the excessive deluge of images and sensations, this could be a sustainable future for the visual arts, I remember thinking to myself. However, in the artworks by the VAA media art students, which have established a certain ‘parallel’ media in the festival’s programme, the most dominant topics were the human versus AI, AR versus RR, and the ‘mapping’ of the future. That evening, a video work in which Siri & Siri go on a ‘date’ gained quite a lot of traction; however, I was more impressed by the augmented reality piece filmed on the Curonian Spit (*probably the most secluded and beautiful corner of Lithuania, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site), in which a character of constantly shifting gender and facial features tries to answer the ever-relevant ‘Who am I?’ while walking in circles in an idyllic pine forest area (which is so site-specific to the Curonian Spit). A little surprising for me was the choice by the youngest festival artist curator Vytautas Michelkevičius in selecting only three VAA students’ video works (at least two of which were already being presented at the gallery) for the open-air screening; however in a brief conversation that we had after the reviews, I was informed that ‘this space [the open yard] with its “own intensities” is very different from a gallery-space, hence the video works manifest in a different fashion here, too.’ Even if I was not fully convinced by such an argument, on that warm night in August, watching the qualitatively executed works addressing significant questions, as well as the nearly euphoric faces of the youngest authors, I refrained from additional queries.

Probably the least ‘formalist’ example of an artistic game in different shapes and media of the same problem or issue (already discussed briefly in the text) could be the minimalist paintworks that contained only a descriptive phrase in black type on a white background (remember the ‘textbook’ artwork One and Three Chairs by the conceptualist Joseph Koshut): Silhouette portrait of a lonely unknown man sitting on a bench, watching the dark sky sliding above him – the sun creates a stretch of light between the clouds, said one of the paintings, which made me fall in love with it just after entering the show. In the excessive deluge of images and sensations, this could be a sustainable future for the visual arts, I remember thinking to myself. However, in the artworks by the VAA media art students, which have established a certain ‘parallel’ media in the festival’s programme, the most dominant topics were the human versus AI, AR versus RR, and the ‘mapping’ of the future. That evening, a video work in which Siri & Siri go on a ‘date’ gained quite a lot of traction; however, I was more impressed by the augmented reality piece filmed on the Curonian Spit (*probably the most secluded and beautiful corner of Lithuania, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site), in which a character of constantly shifting gender and facial features tries to answer the ever-relevant ‘Who am I?’ while walking in circles in an idyllic pine forest area (which is so site-specific to the Curonian Spit). A little surprising for me was the choice by the youngest festival artist curator Vytautas Michelkevičius in selecting only three VAA students’ video works (at least two of which were already being presented at the gallery) for the open-air screening; however in a brief conversation that we had after the reviews, I was informed that ‘this space [the open yard] with its “own intensities” is very different from a gallery-space, hence the video works manifest in a different fashion here, too.’ Even if I was not fully convinced by such an argument, on that warm night in August, watching the qualitatively executed works addressing significant questions, as well as the nearly euphoric faces of the youngest authors, I refrained from additional queries.

To sum up my impressions:

While typing these words, on 8 September, after the festival has just closed, the critic, who is overly stimulated by the incessantly flowing tasks and scattered mental stimuli (do you still remember Okay Kaya? The RAM?) sits squeezing the tail of her keyboard fiercely between the legs. Sometimes I wonder whether this profession suits perfectly the 21st century: by the time one gets the physical and intellectual chance to write a promised review, the experienced dissatisfaction or uplift of the works seen is (often) already diminished; the artists have (sometimes) changed their minds about what they wanted to express in their piece, while it is relatively easy to ‘ignite’ inspiring criticism for the very nature of such an activity: in the blue light of a digital ‘solarium’, in the company of a cheeky flashing cursor, for a time disproportionate to data economy standards, you are serving the ‘truth of art’, even if (most of the time) neither does it become clear in how many light-years, overcoming what analogue and digital obstacles your ‘stoical’ presence in these personal and visual media of (artistic) experience will get to the lives of the artworks that one is criticising. A little frustrated, you still feel you are in your own medium.

*For the insufficiently stimulated:

The hybrid, or meeting of two media, is a moment of truth and revelation from which a new form is born. The juxtaposition of two media keeps us on the border between forms, and pulls us out of numbness. The moment of the media meeting is the moment of liberation from the usual narcosis caused to our senses by the media.[10]

We entered the festival with Monika Dirsytė’s performance ‘Pan/demos’, which happened in a public square in front of the gallery. I would love to devote another piece of writing to this work. On a scorching summer afternoon, when a chanterelle-friendly medium was luxuriating under our Covid-protective masks, we witnessed an incredible challenge of presence (in art, in the presence, at #home, in the pandemic) that required both psychological and physical endurance from the artist. Researching performative art practices in the academic sphere, I tend to keep the events performed by Dirsytė in a certain ‘mental drawer’ called TIME. Her performance practice is characterised by a violation of socially ‘acceptable’ duration, an individual presence in public space and society, or disrupting the standards of such a normative coexistence, which altogether extend the 20th century’s tradition of the performative turn that manifested itself in the anti-institutional discourse of an embodied existence substantially. In Šiauliai, watching the artist’s collapsed body, stubbornly yet recklessly moving ‘forward’ in a self-built glass trap, her calculated moves, saving the depleting energy of the body, her sporty protection of the knees and elbows, her sweat-soaked hair (moving persistently in this claustrophobic space): it would not take one long to ‘assign’ the piece some clickbait hash-tags, such as #body, #feasibility_test & #all_the_other_things_Amazing. And yet, it is precisely such a seemingly obvious testing of her (or even the audience’s) physical capacities that, in some cases, pushes the issues addressed on to the conceptual level of Dirsytė’s artistic research, into a certain ‘shadow’ of the forms of her performance. I would not like to compare Monika’s practice with the artistic strategies applied by the ‘grandma’ of performance Marina Abramović, even if her performance events, which became a total ‘brand’ (unfortunately, in 2020 not a brand of quality any more), used to function exactly as such an uncompromising and ritualistic research-through-challenging of an individual in society, in history, or in mythological time, at the beginning of Abramović’s performative career, that itself has inspired at least a few new generations of performance artists. Monika Dirsytė’s performances (commercially, by the way, truly successful, too) function in much less evident dimensions of duration, or experiencing individual versus universal time and social structuring. Back then, witnessing Monika’s performance, I felt grateful to this artist for the means of expressing what most of us likely feel daily; however, even if we locked ourselves in a glass labyrinth, we would not be able to communicate it.

Another project that blended smoothly into the festival’s celebrations was ‘High! how are you’ by the artist-collab Sheep Effect & Žvėrūna, presented at the ‘undiscovered’ exhibition space of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union in Šiauliai. The complex live compositions of experimental jazz, funk and electronics, performed by Sheep Effect (saxophone), turned into a certain original ‘soundtrack’ of his previous collaboration with the illustrator and graphic artist Žvėrūna, as they both worked together in producing a music video earlier this year. Met by a plastic flowering plant at the entrance to the event, we were immersed in a tiny, calm exhibition space where Žvėrūna’s digital artworks were set up around the room (digital tablets, showcasing brief animated scenes by the artist, were hanging around the space on the traditional white-cube walls), while an imposing black boar (sort of happy with her unpretentious existence in the show) was observing the performance taking place around her, seemingly from the top of a checkered latex cloth, which is sometimes used to cover unflattering industrial surfaces (it might very well have been the neon-striped cage of the boar, which had lost its borders, given the self-sufficient pose of the beast). Hence, even though the animated Žvėrūna’s illustrations (the beast described above was really a digital print) have occupied a certain fluid position between and betwixt the aesthetics of Surrealism, some infantile imagery, and an unarticulated rebuke towards the omnivorous media-person, it was particularly the live ‘soundtrack’ to the event, performed by Sheep Effect, which contained this whole coherence of pure colours and psychedelic ‘footnotes’ in the surprisingly comfortable and meditative event’s medium.

Another project that blended smoothly into the festival’s celebrations was ‘High! how are you’ by the artist-collab Sheep Effect & Žvėrūna, presented at the ‘undiscovered’ exhibition space of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union in Šiauliai. The complex live compositions of experimental jazz, funk and electronics, performed by Sheep Effect (saxophone), turned into a certain original ‘soundtrack’ of his previous collaboration with the illustrator and graphic artist Žvėrūna, as they both worked together in producing a music video earlier this year. Met by a plastic flowering plant at the entrance to the event, we were immersed in a tiny, calm exhibition space where Žvėrūna’s digital artworks were set up around the room (digital tablets, showcasing brief animated scenes by the artist, were hanging around the space on the traditional white-cube walls), while an imposing black boar (sort of happy with her unpretentious existence in the show) was observing the performance taking place around her, seemingly from the top of a checkered latex cloth, which is sometimes used to cover unflattering industrial surfaces (it might very well have been the neon-striped cage of the boar, which had lost its borders, given the self-sufficient pose of the beast). Hence, even though the animated Žvėrūna’s illustrations (the beast described above was really a digital print) have occupied a certain fluid position between and betwixt the aesthetics of Surrealism, some infantile imagery, and an unarticulated rebuke towards the omnivorous media-person, it was particularly the live ‘soundtrack’ to the event, performed by Sheep Effect, which contained this whole coherence of pure colours and psychedelic ‘footnotes’ in the surprisingly comfortable and meditative event’s medium.

The creation and synthesis of the theatre of meaning, and with it the possibility of synthetic analysis, disappeared. In this way, only the incomplete and intermittent answers, partial perspectives, and no advice or instructions for how to talk about it, are left. The task of theory is to find concepts for phenomena, but not to claim them as norms.[11]

[1] Allucquére Rosanne Stone, ‘Identity in Oshkosh’, In: War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 34;

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HEtl9ySN0NQ

[3] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, English-Lithuanian translation by D. Valentinavičienė, Vilnius: baltos lankos, 2003, p. 30.

[4] Cit., ibid (p. 43): Myth is an instantaneous expression of a complex, usually lengthy process. Myth is the contraction or compression of any process, and the instantaneous speed of electricity today adds a dimension of myth to conventional industrial and social action. We live by the laws of myth, but we continue to think fragmentarily and one-sidedly[…].

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luminiferous_aether

[6] Ref.: Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Spegel & Grau: US/Jonathan Cape: UK, 2018;

[7]Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, p. 30;

[8] Error message from Perry Hoberman’s interactive installation Cathartic user interface, 1995.

[9] Quoted from the festival’s publicity material.

[10] Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, p. 71.

[11] Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatic Theatre. German-Lithuanian translation by Jūratė Pieslytė, Vilnius: Menų spaustuvė, 2010, p. 33.

Photo documentation from the ENTER festival by Ernesta Šimkienė and Živilė Žvėrūna