This autumn, visitors to the Town Hall in Vilnius had an extraordinary chance to water grass, which, as if by accident, was growing in its lobby. The artist Aurelija Maknytė had laid it out, sown some radishes, and showcased a spectrum of her botanical musealia. The exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’ was the outcome of the unconquerable force of gravity. We spoke about the Earth, and the traces left on its soft surface at the start of the second wave of the pandemic, after the exhibition had already ended.

Jolanta Marcišauskytė-Jurašienė: I’ll begin by asking: Who are you? I know it’s rather an awkward question, but I once read an answer to it by Alfonsas Andriuškevičius, when asked by a philosopher friend of his, and I’m amazed at how many thoughts actually come to the surface when you ask yourself sincerely …

Aurelija Maknytė: The first word that comes to mind (or shoots out of it), without thinking, is human. But then, in an instant, the brain’s google contextualises the word visually: it shows the great Vitruvian nude by Da Vinci, framed in a square and a circle. If we were to take away the square, that human would roll around like a clown in a circus. A square has corners, so the human inside it feels more secure. The geometrically framed, firmly standing human seems to be at the centre of the world. So yes, unfortunately, I am human, and that’s it. With everything that it entails. If I had a second chance to answer, I’d probably call myself an artist, because creative work is probably the most important part of my being. The eyes and the brain are always involved in creative processes. I see meaning in that; it feels good to be there.

JM-J: A few years ago you bought a piece of land on the River Širvinta, and now it seems you spend more and more time there. Tell me about that Land of yours. The last time I visited, it looked as though you were acting according to the place, as if you were listening to it.

AM: It’s hard to say if a place makes you act in one way or another. It’s quite wild, so it’s enough not to intrude on it too much, and simply enjoy real life in nature. Of course, in order to be able to live there, I inevitably have to do certain things: I weed the paths, I brought a trailer, I plant various kinds of flora, both for food and decoration. So we split our spheres of influence: I’ve left more than half the land completely untouched, I don’t cut anything there, and so it all falls down and rots; normally such places are called abandoned. Well, yes, that urge to ‘look after’ something, what an odd thing, I feel it instinctively! I even remember in my childhood how I wanted to grow, to take care of something, so that it would be mine, so that it would live according to a scenario I had planned. Another interesting thing is that I somehow have this understanding of which things in nature should be respected more; it’s a kind of hierarchy. For instance, while making paths through the undergrowth, I had to cut down a number of trees and bushes. And while I was doing that, I realised that cutting down an ash tree or a bush was not nearly as difficult as cutting down an oak tree, as though the oak was more valuable. Although it is a wild tree, it is rooted culturally, its cultural significance is treasured so much by certain traditions. And so it’s hard to see those things from a different point of view. We are not wild animals, so even if we live in nature, we live according to cultural guidelines.

‘From Life’. Material from the infrared camera with a motion sensor. Work in progress started in 2018. The soundtrack is a collection of natural sounds recorded in nature by the sound artist Audrius Šimkūnas. 2020

JM-J: How did you decide to acquire that piece of wild land? How do you get on with the neighbours?

AM: It was a kind of childhood dream to live in the middle of a forest. I used to imagine I was a hermit, keeping animals and cultivating plants that are essential for survival. I’ve always been fascinated by stories about recluses, who choose this way of living, or who are cast out by society. Robinson Crusoe, Rockwell Kent, or just a wanderer lost in the vast taiga. As a teenager, I was particularly inspired by H.D. Thoreau’s book Walden: Or Life in the Woods. I underlined the sentences that were important to me at the time … And a couple of years ago, I opened the book, and couldn’t understand why I chose those parts … I read it with adult eyes, and I was even more surprised by the didactic tone of the book, by how many things were simply unconvincing … I didn’t like it. And so it seems that all periods of our life have particular books to which they correspond. Yet I am building a small annex for the winter on my own personally acquired Land. It will be attached to the already-existing summer trailer, and since it’s tiny, I call it the winter kiosk. So, I can see now that its size is very similar to the one described by Thoreau: a small hermit’s house. By the way, that little house of Walden’s inspired the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, the maths professor, who sent letter bombs from his tiny home. It was a rebellion and a struggle against technological society. It seems he started doing it when some road construction work began to destroy the wildlife around his home. Like those flaps of a butterfly’s wings … everything is much more connected than you might think.

My neighbours live quite far away. I deliberately looked for a place where I wouldn’t have to negotiate the height of the fence and other things like that, which would be unavoidable elsewhere. While was looking, I learnt to distinguish between an are and a hectare. And I now own a pretty decent area, 5.4 hectares. It’s easier to visualise it if you compare it to about 90 private lots in a suburban neighbourhood. I feel safe here. It’s enough for me to encounter all my students and pupils, about a hundred every week, to socialise, to talk through everything. I’m not completely cut off from my neighbours, either. I know them a bit. I buy products from them, and before the lockdown I would often give some a lift home. It’s a great opportunity to learn about the place where I spend so much of my time.

JM-J: What about your animal neighbours?

AM: Everything is straightforward with them: there’s space for us all. Some badgers live nearby, and foxes and raccoons drop by on occasion, stray dogs too, and sometimes cats. Deer live here. Birds hatch their eggs in their nests and in the undergrowth; and, of course, some of them eat the cherries. But the cherry trees are so tall I wouldn’t be able to reach them, so let them enjoy themselves! But there are some conflicts with mice. I must admit, it’s hard to deal with them, to share the space … They make too many holes all over the place, they gnaw tulip bulbs and other things. However, we are going to make something together: I’ve collected some cherry stones that are almost entirely eaten through by them, and they’re ideal for jewellery, so we’ll make some beads and earrings together.

Mouse earrings

JM-J: When you start thinking about man’s relationship with nature, it seems it has recently become a lot more complicated than we would ever have expected it to be. On an everyday level, before the pandemic, nature consisted of animals, trees, water, landscape, all persistent insects, fruit tree-destroying pests, and, well, us. Before coronavirus, which itself jumped from animals to humans, I had never thought so much about how solitary the human body is in relation to other forms of nature. Despite our intellectual development, our bodies have remained animal-like, prone to the same diseases, the same viruses …

AM: Yes, now is the perfect time to remember that humans are animals: mammals, vertebrates, warm-blooded primates. Maybe the inventory of mammals should include not only elephants, rats, bats and others, but also humans? Perhaps we would start to see ourselves in a broader and more natural context. And in terms of our biological vulnerability … with advances in medicine, even the weakest survive; therefore, natural selection doesn’t happen any more. And perhaps that’s why we have become more vulnerable. A paradox: we are progressing, but at the same time, we are becoming weaker, since the micro-organisms attacking us are developing at their own rate. The pandemic is indeed a dramatic period, but it’s a good time to really think about the minute scale and brittleness of our world, as well as what a vulnerable part of nature we are. We are not almighty gods, rulers of nature, that can change the flow of rivers without fear of the consequences.

JM-J: The philosopher Gintautas Mažeikis says that there are three types of person: rational, logical, practical Homo Sapiens; playful Homo Ludens; and the third, which we know the least, Homo Ridens, the laughing one. We think there is only one species of human, because we can reproduce with each other and we look similar on the outside. It sounds somewhat comic, until you start thinking about the differences between the real people you know, the differences existing inside the species that are noticeable in our everyday lives. What species do you think you belong to?

AM: Biologically speaking, there have been many types of humans. It is said that they would even cross-breed; however, the offspring couldn’t have children. It’s very hard to tell which kind of Mažeikis’ species describes me best (smiling). Oddly enough, the laughing and playing types are distinct. To laugh and to play are such similar activities! And I doubt that Homo Sapiens is actually practical: one can only wonder why there isn’t any Homo Nonsapiens or Homo Destructus, the destructive human, since I think in reality it comprises a large part of us … On a more serious note, it’s hard to categorise myself. I think I’d be a hybrid between the laughing and the playing one.

JM-J: The art critic Agnė Narušytė, the curator of your exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’ in the Town Hall in Vilnius in September, once said that artists are the sensitive part of humanity which senses imminent catastrophe much earlier than the rest. Endangered species are usually doomed to live in small areas, in constant threat of extinction, of being eaten by something stronger (perhaps that same Homo Destructus?). These vulnerable species can hardly go on living in this fast-paced, consumerist world, in noisy cities with their gleaming pavements and glass towers. How do you feel in this contemporary world, and in today’s Vilnius?

AM: No type of sensitivity will help in the face of that slow-motion catastrophe. Certain important decisions have to be made on a national level, but even a single individual can contribute and improve the situation. However, sceptics insist that nothing better will come along; it’s already too late. Meanwhile, I believe in the power of science; perhaps our children and grandchildren will think of something, and solve the chaos to which the generations of recent centuries have been contributing … Oh, how I want to believe in this progress, which will give us the tools by which we can live in harmony with nature, without destroying what we have created.

I can’t believe how ignorantly the green spaces around our towns are managed. I watch the struggle for those mature trees. I used to participate in the protests myself. However, my arms get heavy, and a feeling of despair comes over me. You get weary, angry, and run to your personal Land, where you can regain your equilibrium and be safe. The city, with its clean, epilated, glossy facade, is becoming increasingly foreign to me. There is no room left for nature. And it’s not only Vilnius’ problem. Sadly, when I pass a small town in Lithuania, I see how alike they are becoming! It feels as if all municipalities have recently bought the same bricks and the same trees. Well, perhaps our children will live to be able to stand in their shade, if they take root. I’ve seen such little broom-sized trees wither, unable to adapt to the environment, only to be replaced by some new brooms. What a pity. It feels as though it’s a part of some business plan.

‘From Life’. Material from the infrared camera with a motion sensor. Work in progress started in 2018. The soundtrack is a collection of natural sounds recorded in nature by the sound artist Audrius Šimkūnas. 2020

JM-J: It seems to me that ‘Nature Cabinets’ works as an organic continuation of your life on your Land, and of all the other fragmented and scattered ideas you’ve tried out so far, a kind of sorting out, some poetry of relations between species, between connectedness itself.

AM: Yes, being on my Land has really contributed to my previous ideas, and to forming a collection from my found objects. Never in my life have I had a studio solely for creative work. All my projects and ideas would take shape in the flat where I lived. That flat is now completely filled up with boxes and objects that end up in exhibitions, or otherwise help me work out certain things. So now that piece of Land I own is like compensation for all the time I didn’t have a studio! Now I have a 5.4-hectare studio! What’s really nice is that I can think while walking around it. I understand how walking affects the thinking in a very positive way. But that’s nothing new: the peripatetics, with Aristotle at the head of them, all practised philosophy while walking. By the way, Aristotle said that the Earth’s changes happen too slowly for humans to notice: our lives are too short. So it worries me that certain changes can now be observed within the span of a single human generation.

JM-J: Your exhibition can also be understood as a retrospective, which seeks to determine how you would observe nature in childhood, as well as your previous works (such as Burning Slides or the rabbit’s character), within a web of new significations. Have you yourself thought of such retrospectivity?

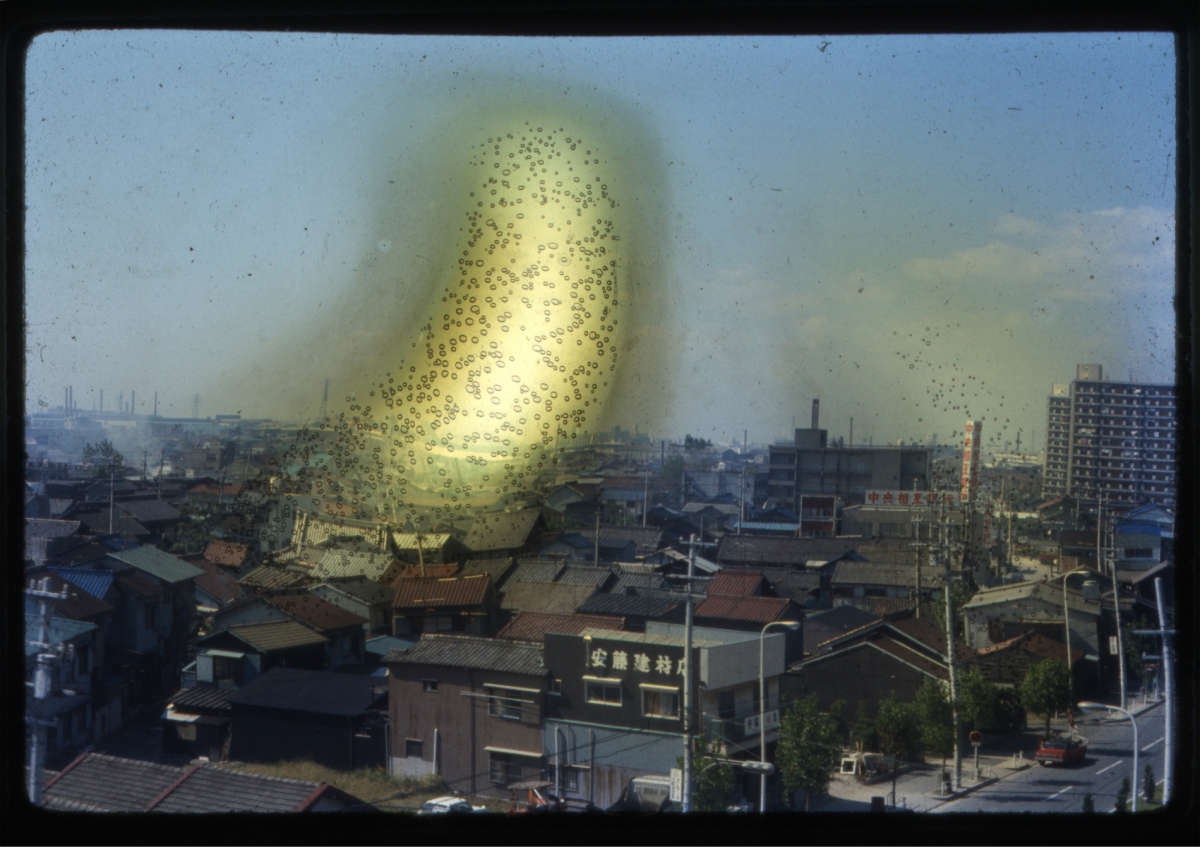

AM: I haven’t thought about retrospectivity; however, the fact that some works are connected to others, that they’re from other exhibitions of mine, is true. But they tend to change slightly; to me, that’s very interesting. I like it that the work lives a separate life, that it changes, and acquires more hues, or a new meaning. The rabbit, by the way, carries out a variety of activities which I don’t even follow myself: for example, it often participates in Christmas meetings with children. I lend out its fur for all kinds of purposes with pleasure; I like it that it continues to live in different contexts. A few other art objects of mine have shifted in a similar way. Burning Slides also takes on various forms; in this exhibition, they got rid of the link with the media, and showed themselves without the frames. Father’s Act has come a long way too, from being a printed text on a piece of paper, to one written straight on a wall, in which case the important aspect is the graphite dust falling down, as though it were ash.

JM-J: The classic opposition between culture and nature seems to be at the heart of your exhibition. Interestingly enough, this time it’s spelt out not only by the natural or the cultural origins of the objects presented, but by a consideration of the place itself. You’ve brought stumps from your Land to the Town Hall, and you’ve cut out an area of grass from your meadow, whose dimensions are exactly those of the Town Hall’s ground floor.

AM: Yes, relations between culture and nature are becoming more and more interesting for me to brood on and create from. These relations have so many nuances, so much depth, so many layers! The subject is absolutely inexhaustible! The more I learn about it, the more it draws me in, and the more it offers. The stumps that you mentioned have returned from the Town Hall to their original place in the meadows; while the grass floor, that tamed meadow, has been shared out piece by piece with my friends. I have taken parts of that cultivated meadow myself, they seem to blend in perfectly well with the natural one. I’ll be keeping an eye on how it changes, how it becomes wild and untamed. Since cutting out the area from my wild land according to the Town Hall’s ground floor plan, at a ratio of one to one, I’ve observed how ‘cultural’ it has become: such a sought-after, mown meadow doesn’t have as much diversity of species; nevertheless, it is much more convenient for humans, since there are few ticks living there, so it is safe and comfortable to lie down. I’ve left a couple of trees growing there naturally: they are like disorganised columns from the Town Hall. I’ve also planted a couple of cultivated, grafted plants, and in the spring a garden will appear there. I’ll probably dedicate it to the architect Laurynas Stuoka-Gucevičius, who rebuilt the Town Hall. While I was making that wild Town Hall plan in my meadow, it was fascinating to think how a human chooses where to build a house or found a city. That’s probably how architecture, as a form of art, was once born. Vilnius was in fact dreamt of! What an abstract and simultaneously surreal creative process!

Aurelija Maknytė ‘Burning Slides’, 2012 – ongoing

JM-J: Your creative work, in my opinion, is permeated by magical thinking, which resembles a playing child’s world-view. Just like a child, you play with resemblances, with shifting and overturning significations, making known things seem odd. For instance, you made a wreath of oak leaves partly eaten by gall wasps. You drew attention to how much an animal’s pelvis resembles a mask we tend to wear in our childhoods, or how sheep on a wall hanging look like lions, as well as gnarled stumps.

AM: Well, nature is full of miracles, which only have to be noticed and presented; then we can understand how closely connected everything is, how beautiful everything is! And that washed-out line between the state of being alive and dead is particularly fascinating and inspiring to me: the gall wasp beads from the exhibition have been returned to nature, and in the spring they will hatch into living insects. The pelvic bones are at times tried on by visitors to the exhibition. Yes, this bone is not only a mask, but our first doorway into the world, the first frame we encounter.

JM-J: Like a true naturalist, you tend to notice anomalies and oddities. What thoughts came to you when you found that coconut in the River Širvinta? Are you still hoping, as you did a long time ago, to find a dinosaur’s egg?

AM: Well, we have living dinosaurs even today: take crocodiles. But yes, the coconut I found between the branches of a fallen, rotting tree really surprised me. It was like finding a whole palm tree, or a crocodile. It was probably left by a canoeist, but it became a message from the future. A temperature of 18 degrees is warm enough for a palm tree like that to grow. And mantises, insects that are common in warm climates, are already successfully breeding and hibernating here in Lithuania.

Aurelija Maknytė ‘Bunny Man’, 2009 – ongoing

JM-J: Climate and societal change seems to be accelerating. My daughter and I were reading a book. After looking at a picture of a crowd of people, she asked, naturally: Why are all those people not wearing masks? I thought, yes, her generation is one that will see our abnormalities as something completely normal. One day, it will be normal to grow orange trees among our apple trees. And to come down with malaria. How do you see these global changes, and the role of humans in them?

AM: Well, we can see and feel the most obvious changes: we do not have winters like before. It is known that the sixth extinction of species is happening right now, too. However, we can’t see it so clearly; therefore, it doesn’t bother us much. Just yet. Industrial farming really exhausts the soil, but we just spread fertilisers, and let’s go! Business is business. What extinction?

This past winter was the warmest in the history of meteorological observations. And the first one which was snowless. Of course, global waming will not affect our country as much as it affects the south. However, in some countries, local wars have already broken out; they are fighting over places where you can get water. By the way, I hear more and more often that the wells in our countryside are drying out. There is no thawing snow, the underground waters are drying up. This influences my existence on my Land, too. I have been planning to dig a well, but now I see how risky that kind of water extraction is. I’m thinking about a borehole … And I’m extremely happy that there’s a river nearby: it’s much easier to get through the hot summer days; however, the drought has already turned the river into a shallow stream in some places.

The pandemic is not only a medical problem, it’s caused many social problems. Social inequality has become acutely apparent, and in the face of all of this, certain great achievements by humanity seem so empty and meaningless …

Aurelija Maknytė, ‘Nature Cabinets’, Town Hall, Vilnius, 2020

JM-J: It often seems that contemporary art that is aimed at some ecological problem attempts to start off with the problems of Anthropocene. It analyses the consequences of human activities, and so on … its tone becomes didactic, it starts resembling an information leaflet, but in visual form. Right now, this is a fashionable topic. How do you feel in the context of such discourses on ecological art? Don’t you want to look at it ironically? What do you think of the pseudoscientific aspect, of the speculation of emotions? It all sometimes seems utterly boring to me …

AM: There you have it: when we talk about something too didactically or abstractly, there’s a risk of inducing completely opposite reactions to what is intended. ‘Don’t do it, it’s bad,’ is not only boring, it also induces rejection. As I was talking about extinction and ecological problems a few moments ago, I felt rather uneasy; after all, I’m not an expert in the field. I use terms that are quite popular, and so more of the same talk simply makes listeners’ ears hear less, and it makes their eyes see less … There’s a lack of scientists who can explain things to the general public in comprehensible terms. Even the pandemic is presented to us mostly by politicians, and not by scientists or other professionals in related fields. This situation is perfect for pseudoscience to emerge, and then what’s left for you is a tin foil hat.

It’s quite obvious that the subject of nature is becoming increasingly popular in art. Perhaps that’s good: some engaging and quality pieces crystalise out of the huge quantity. Personally, ecology and nature have always been my favourite topics, ever since my childhood. I was going to be a scientist, to research the natural world, and maybe even save it a little. I was doing well, winning prizes in national biology olympiads, and studied biology at Vilnius University. I read an article around 1980 that said that in the near future oranges would be growing here. That fact made quite an impression on me; but there was no hint of catastrophe, it just sounded like a funny guess, even though it was scientifically based. Well, while there are still no orange trees visible from my window, I am happy that the Earth keeps holding us down, and does not let us fall off it, like some useless, harmful piece of dust. And although my relationship with H.D. Thoreau’s claims is rather complex, one of his thoughts fits well here at the end: ‘The surface of the earth is soft and impressible by the feet of men; and so with the paths which the mind travels.’

I really hope common sense will safeguard our harmonious life on Earth.

JM-J: Thank you for the conversation.

Fragment from the exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’, 2020

Aurelija Maknytė, ‘Nature Cabinets’, Town Hall, Vilnius, 2020

Fragment from the exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’, 2020

Fragment from the exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’, 2020

Fragment from the exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’, 2020

Fragment from the exhibition ‘Nature Cabinets’, 2020