Edith Karlson (b. 1983) is an artist based in Tallinn, where, besides doing her own creative work, she is also a teacher at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Her sculptural works can be recognised by their monumental forms and fleshy materiality. Karlson’s sculptures and installations resemble Medieval relics, as well as funky circus troupes and phantasmagoric nightmares, where the old and new worlds clash in one apocalyptic vision. The artist’s works have been described as dark fairy tales, as they tend to look like fun playrooms full of monster-like creatures: different animals, including ancient creatures such as dinosaurs spitting artificial blood, as well as reptiloid families and anthropomorphic phantoms. They all seem to be tools to create allegories for strong human emotions and fears surfacing from the deep dark pit of the unconscious.

Karlson, as well as Jass Kaselaan, Eike Eplik, Art Allmägi and Kris Lemsalu, is one of the ‘it’ generation sculptors that some decades ago brought sculpture to the main playground of Estonian contemporary art. Like the other artists mentioned, she introduced a different, more playful, approach to making sculpture, where the materials, forms and space all become an important part of a performative, almost carnivalesque type of world-building. Just as in the work of Eplik and Lemsalu, Karlson’s is also sometimes softened by the artist’s use of bright, Pop-ish colours and cute animal figures. Animals are the main protagonists in most of her projects, and continue to be the main medium through which to express the anxiety that comes both from personal experience and things happening in the world at large.

There is an obvious physicality in her work that has surfaced most vividly in well-known projects such as the ‘Drama is in Your Head’ (2015-2019) series and Doomsday (2017). Sculptures of different human body parts and the dead animal flesh and bones in these works create an altarpiece-type of ensemble or fields of archaeological digs, requiems for a Frankenstein-like world that is producing new monsters every day. In her latest projects, the exploration of fear and healing is done by using snakes as the main symbol. They appeared as giants in the exhibition ‘Do Come in, the Door is Open!’ (2020) with Mary Reid Kelley and Eva Mustonen at the KUMU Art Museum. Now they have recently appeared in colourful ceramic forms inside a transparent plastic suit (another new element appearing in Karlson’s work) at Art Fair Basel, where she was represented by the Temnikova & Kasela Gallery.

It so happened that our conversation with the artist took place in two parts. The first was at the beginning of the summer, when Karlson was still working on the sculptural installation specially for Art Fair Basel, and the second time was just after the fair at the beginning of October, when she was preparing for her solo show at EKKM, Tallinn.

Edith Karlson. “Return to Innocence”, EKKM Tallinn, 2021. Photo: Paul Kumet.

- June 2021

Šelda Puķīte: I imagine that the pandemic has been hard for all of us. It has mostly been emotionally hard, but for some it has been devastating dealing not just with the constant feeling of imprisonment, but also with financial struggles, illness and even death. A lot of human neuroses, like territoriality and intolerance, have surfaced. To add even more, the climate emergency raised by scientists and activists has intensified, urging us to end the Anthropocene era. When I think about your work, I also think a lot about the space we live in, human and non-human life form relations, death, melancholy, and also irony. How do you look back at this past year and its impact on the world, and how it has been for you personally?

Edith Karlson: I gave up all my job-related worries, because I understood that the situation is as it is, and I just had to wait and somehow enjoy the countryside. I surrendered, and it was a nice feeling. For the first time in my life, I saw how spring came. I literally saw how the grass started to grow. And as my house in the country is on an island, it meant that I was really cut off from the world. It was an indescribable period. Peace. No worries. I don’t have an art studio there, so I could not do my art-related work, and everything was postponed anyway. My friends were living in Tallinn, so they had a totally different experience. But then the summer came, and the situation somehow reverted, and all the works which had been postponed started again. And now, for different reasons, I have had the worst year of my life (laughing). I have an apartment which I have been renovating for two years, which means I have been homeless. And then I had two water accidents in a row. My apartment had just been renovated, I had just moved in, and then I was homeless again. What is the word for dealing with everyday problems?

ŠP: The only word that comes to mind is ‘domestic’.

EK: Domestic, yeah. I’ve been dealing with this every day. I’m so, so tired, and I also have a five-year-old kid who did not go to the kindergarten because of the pandemic. Then, of course, all the projects that were postponed are now happening at the same time. So basically, I’m having panic attacks almost every night.

I have been thinking about giving up my job, because I can’t take it any more. I have a huge show coming up at the end of October at EKKM in Tallinn: the whole premises, which is three floors. I have not even had a moment to think. And then there are other projects, like Basel [Art Fair Basel, Statement section, represented by the Temnikova & Kasela Gallery] where I will present a super-difficult installation. I mean, difficult to make. Domestic life and art don’t go together. I’m not the kind of artist who uses these domestic vibes to integrate into my art. I need my thinking and observation time, which I think is for very privileged people.

Edith Karlson. Short Story. 2019. Skeleton of a seal, greenhouse plastic. Installation view at exhibition “When You Say We Belong. To The Light We Belong To The Thunder”, Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia. Photo by Paul Kuimet.

ŠP: I was about to joke that maybe if you don’t have time to think about the EKKM show, maybe you can implement these domestic problems in your project. But you’ve already said that you don’t want to do that.

EK: It will probably sneak in anyway, in a way that I will probably not even notice myself. One day I was sitting in my studio and making soap dishes from clay. I made three after I had flood problems in my apartment.

ŠP: Well, in these post-pandemic times, soap dishes have gained a totally different meaning.

You have been really busy with your domestic problems; but have you also tried to soak up what is happening in the world because of everything?

EK: Have I noticed the global pandemic from my little world? (laughing) Of course, I feel it with my whole body. At the same time, I also have to be really honest that most of my life is, in a way, egocentric. I live in my studio, where there are no people. My house in the country is in the woods. The only people I see are my child and my family. The global situation is very stressful, and I am constantly worrying about everybody. But at some point, you have to stop, otherwise it is too much for a person to bear.

ŠP: The work Short Story (2020) which you created before the pandemic is resonating with the new times, including the topic of climate crises and the human footprint on the animal world.

EK: I have been thinking about this work a lot. It’s a short story about everything. In a way, a very simple work. It’s all about humans, all the shit that is caused by humans. This work represents what ‘human’ means to me: manipulation, greed, all those manly sins that lead to global catastrophes.

ŠP: The shift that I already noticed pre-pandemic was the strong return of magical thinking. It can be a great tool, especially for creative people, but it can also trigger neuroses, giving birth to conspiracy theories and fake news preachers. The fantastic and magical, although many times with some dark vibes, seems to be present in your work as well. What draws you to the realm of the magical, and what purpose does it have?

EK: What you said made me think about what is happening in Estonia. The weird gatherings of Hippies and Nazis together. Definitely interesting from an anthropological point of view. It’s actually funny what you said, as I have never heard anybody using the word ‘magic’ to describe my work. You kind of caught me, because all kinds of fairy tales have been guilty pleasures for me since early childhood. When I was still studying, it seemed very elementary. You have to know what others on the art scene are doing. You have to be …

ŠP: Up to date.

EK: Yeah, updated all the time. You have to know what’s going on. But then, at one point, I understood that this doesn’t work for me. I made a decision not to be updated. I don’t want to know anything about trends. That’s why my studio is outside the city. I do, of course, go to exhibitions, but not to every show possible. If I get information all the time about what others are doing, it makes me very anxious. I teach at the Art Academy of Estonia, and what I have noticed sometimes is that students all know exactly everything about their work before they even start to do anything. They basically google first to see whether it has already been done, whether this kind of technique has already been used, and so on. I think it kills so much.

ŠP: I guess that explains why you go to this ‘other’ world. You disconnect from the existing world, from active living inside the area of the contemporary art world, and instead exit to some other place.

EK: Yeah, well, something like that. It is a kind of protection, because I have a brain which constantly goes like dkfgj495uhi4uthu. So I have to survive it somehow. And there is another thing. I am not a happy person, I never have been. If for a moment I am happy, that means I’m not doing anything. So what I learnt from the first lockdown is that I don’t have to do anything. I could live in the country and be very happy watching the grass grow. But if this happiness goes away, then the struggling and depression start, which also drives me to make my things. It’s my engine actually.

ŠP: I can sense dark vibes in your work.

EK: Let’s say, the father of my child doesn’t have an easy life with me (laughing).

ŠP: Then it’s good that you are not totally domesticated. What might happen is that this dark vibe could take over your home. Now you can put it into your artwork. And what is better than having a fight with some materials?

I would also like to ask you about your collaborations. You have been working for, helping out and collaborating with several artists. In 2011, you also collaborated with the legendary Sarah Lucas and the art collective Gelitin on the exhibition ‘Lucas-Bosch- Gelatine’ at Kunsthalle Krems in Austria. Later, in 2015, you assisted Sarah Lucas in the production of her solo exhibition ‘I Scream Daddio’ for the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Tell me a bit about these experiences, and what the most important thing was that you gained or learned from them?

EK: It was never just a job, because I know them, they’re friends. When we get together, we always have lots of fun. It’s not like a typical job, from nine to five, where you are working your ass off. Well, you are, but it is also about gathering all the friends around the world and working together. I am quite skilled professionally; that’s one of the reasons I have been working with these people. I think it’s fair to say that I already knew how to do things.

ŠP: But learning is not just about gaining technical knowledge; it’s also about observing how others think, how they approach things, how they think about making exhibitions.

EK: Well, you can’t see that kind of art production in Estonia. They have lots of money, huge productions, but you can also see a hierarchy there. All the people I have been working with are the best, but at the same time, all those huge institutions and all the hierarchy thing is gross for me. The bigger you are, the bigger the systems are that you are involved in. This is what I have seen there. Because Estonia is so small, you can’t see it here. And talking about learning, I then realised after seeing it all that I like Estonia the way it is, and that’s why I like working here.

ŠP: Fair enough.

EK: And then there are art messes. I mean Art Basel, and so on. They represent exactly what I am talking about: hierarchy. That’s why I am so happy and grateful for having a gallery [Temnikova & Kassel], I mean Olga [Temnikova], because she saves me from that. And if an artist says bad things about gallery owners, then I would say that they don’t know much about life.

Edith Karlson. Sisters. 2019. View from exhibition “Do Come in, the Door is Open!”, Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo.

ŠP: Talking about more interesting collaborations, you participated as one of the three artists, together with Eva Mustonen and Mary Reid Kelley, in the KUMU exhibition ‘Do Come in, the Door is Open!’, curated by Triin Tulgiste, which took place at the end of 2019. It was part of the museum’s programme focusing on women artists from history, as well as contemporary women artists. At the same time, you participated in another exhibition, ‘Sisters’, at Tallinn Art Hall, curated by Tamara Luuk, where you were combined with the older-generation painter Mall Paris. The history and identity of women in the arts have recently become a hot topic again. How do you see yourself in this new feminism movement in the arts framework, and what are your thoughts on projects that consciously underline women artists and women’s voices?

EK: Well, it would be politically correct to say, good! (showing a thumbs up). The word woman for me has somehow lost its power. It’s like with everything else, if you use it too much. You can’t choose artists by gender, because, what about the work? I mean it’s a very, very difficult topic. My boyfriend, he organises music festivals. And he’s been criticised because there are too few female artists. My boyfriend is a feminist, and I know how he’s been struggling to find female artists.

For me, in an ideal world, there would be no he or she, just the things people do. But I also understand very well the problem, especially in bigger cities which are somehow dominated by males. So I understand why this polarisation is needed right now.

ŠP: You have had commissions for public sculptures as well. You participated in Kristina Norman’s ‘After War’ project in 2009, making a copy of the controversial Bronze Soldier in Tallinn. You also made a bust of Brigadier General Mart Tiru. But the most interesting projects have been ones where you bring your work to well-known public monuments, and create dialogues with them. What urged you to make these public, performative sculptures, and are you still interested in working with public open-air spaces?

EK: Yeah, that went well. I was on my way transporting my rhino sculpture [from the installation Circus, 2010] to a cinema to decorate a room, and this hated statue was on the way, and Kris Lemsalu was also with me. So we quickly made this action there. We took the rhino out and took photos. And what I like most is that I sent a photo to the Estonian magazine Eesti Express. You can send them a picture and they will pay. People can be active and send weird things. I sent the picture and got some money. Back then I was even poorer than I am now (laughing).

ŠP: So it was all for the money!

EK: It was about money, fun, and also showing what I think.

ŠP: How many similar activism sculptures have you done?

EK: Actually, I think it was a one-off thing. But I’ve made another public sculpture. That was Peeing Woman (2006). I am actually going to remake it for an exhibition at KUMU next year.

ŠP: Will it be in a group show?

EK: Yes, a group show about the nineties. It is about that moment when old-school sculpture was fading away. When I was studying, I experienced both sides. The old-school sculpture department, where no one used the word installation, it was just sculpture, you know, pure modelling and sculpting things; and then at the end of my studies, the new professors came, and they started to totally change the scene. So when I stepped into the sculpture department, it was the most unpopular place to be. I actually really loved that. It gave me a weird power to show that sculpture is actually cool. At that time, graphic design was ‘the thing’ that you would want to go and study at art school, but I really felt that the place where I was studying had so much potential. Slowly, it started to get more and more popular.

ŠP: So the joke’s on you. Every time one of your names, like Eike Eplik, Art Allmägi or Jass Kaselaan, comes up, it is always in connection with you all being part of this young, talented generation of Estonian sculptors. You have become ‘the thing’. Also, you did not consciously come together as a group, you blossomed one after the other.

EK: Well, it would be cool to think like that, but I’m not stepping into this role.

ŠP: Too much responsibility?

EK: Yes.

ŠP: Why do you think sculpture became so popular in Estonia?

EK: When I came to the sculpture department, there was only a box of clay; it was the only material there. The water was just standing there. The teachers seemed to be tired, not really caring about the students. Maybe our course was reacting to this nothingness. There wasn’t even toilet paper in the bathrooms. I didn’t actually learn anything in my BA studies. I didn’t even know how to make a mould. Somehow, this triggered this fighting mode. I really felt that it is a cool art form when there are mostly paintings in exhibitions. Anu Põder was actually one of the coolest older sculptors; also Terje Ojaaver. I use word cool because I was young and I wanted to do things that are cool.

So there was nothing really going on. And then came the new professor [Villu Jaanisoo] who tore everything up. He fired everyone there. It was huge. Everyone hated him, but he really changed the game, and also foreign teachers and professors started to come. The idea about what sculpture is, and what you are doing, and what you are using, all changed. But I must say that even without that professor, I always saw a sculpture not like an independent piece, but like a room, an environment. I have always thought about it a little larger, actually. I must say, I am not so much a details person. I appreciate them, but I would not devote a long period of time to making small pieces. For me, work is the whole package, I mean, smells, air, sound …

ŠP: Material.

EK: Material, everything.

ŠP: When I look at your works, their material and form, there is something delicious about them. They are a bit like melted butter. The material feels wet, and in constant movement.

EK: Yes, this is my thing. I don’t like finished things. I even have this in my apartment, that I don’t feel good if it is totally licked clean.

ŠP: Do you also like the errors and wrongness that happen during the work process?

EK: Yes, and that also applies to symmetry. I really like doing portraits. I remember from my time at school that I felt bad because I had this fault, that I could not do symmetrical faces. And then I let it go. I think I can now say that there is no such thing as totally symmetrical faces anyway, and asymmetry works for me. There is more life and flesh.

Edith Karlson, Drama is in Your Head V. Exhibition view, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig, Germany, 2018. Photo by Christina Vetesnik and Alexander Schmidt

ŠP: I can’t skip the question about animals. One of your very first shows was devoted to a circus and dog show; later, birds appeared in your installations; then beautiful, decorative pearls of rabbit shit, dinosaurs, reptilian creatures, worms, snakes and seal skeletons. They are always present in your work. You said many years ago in an interview that they help you subconsciously to tell your stories. Could you elaborate a bit more on this: what do you mean?

EK: I have always, as far as I can remember, been a huge fan of animals, and I have never stopped loving and admiring them. I probably started to use them in my art because I did not want to use the human body or the human figure, or anything too human. Whatever problem or feeling I try to show with my art is already very human anyway. I am just trying to remember what my first work was where I used animals. I think it was the work with the stalker dog [‘Drama is in Your Head’, 2011], I’m not sure. So I started to use them to tell human-related stories. Now I play quite a lot with abstract kinds of objects as well.

By the way, I am now collecting deer shit. I had my own rabbits, so the shit was collected from my own rabbits. And also from the zoo, because one rabbit died and then another one, so I had to get more. But now I collect deer shit from my place in the country. It is very beautiful; even my child collects it for me. He really likes it. We have a hobby together now.

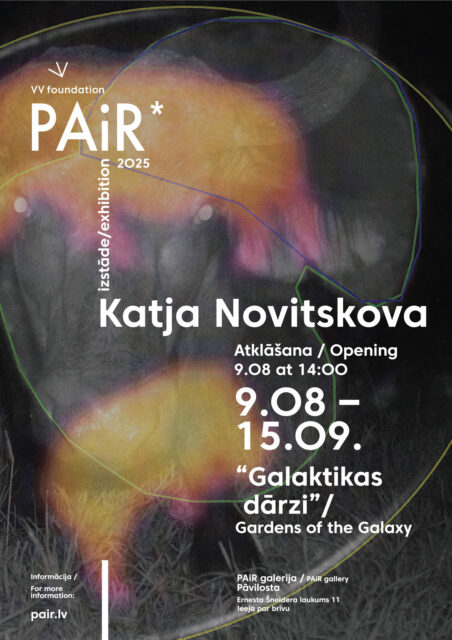

ŠP: The Temnikova & Kasela Gallery will be presenting your works this year at Art Basel, one of the most important art fairs in the world. Can you say a bit more about what visitors will be able to see there, and what else you are doing at the moment?

EK: I’ll gladly talk about it. Let’s go! (turning the computer camera to show her works: snake sculptures).

ŠP: What kind of material are the snakes made from?

EK: Ceramic, and I have lots of them. What I am planning to do is to make a transparent suit. So there will be a transparent suit standing, and inside there will be snakes.

ŠP: Oh, pretty scary.

EK: Yeah, it sounds like it, but it’s just so impossible to do. I’m struggling so much. The snakes are fragile. I’m already tired of the work. And then I also have this kind of suit (showing the camera a sculptural form that looks like a transparent suit).

ŠP: Is there a particular reason you started to make snakes?

EK: For me it’s always difficult to remember where it all started, because all my works are somehow connected. I have been making all kinds of snakes for a long time now. And it all started with this sister theme, actually. In Estonian, ‘sister’ also means ‘terrible’, like ‘terrible sisters’. I have noticed that women have very interesting relationships with each other, especially sisters. There is love and hate, and they can be so nasty to each other. So I started to play around this terrible sister theme, and then it sneaked in somehow, the snake element. And I haven’t finished yet, so I’m probably going to work with this snake business little bit more.

All my life, I have been afraid of snakes. They have something about them that makes people phobic. But then I got over it somehow, because my friends had a snake, and I had an opportunity to touch it and feel it, and I realised it’s just an animal. In Estonia, for example, there are only three kinds of snakes: only one is poisonous, but not deadly, and one is actually a lizard which looks like a snake. Every snake in Estonia is protected, and they definitely should not be killed; but people are just so scared of them, and there are so many false stereotypes about them.

ŠP: After the EKKM show, will you relax?

EK: No.

ŠP: All next year is also booked?

EK: Yeah, it is. It’s weird, so many things. Ah, by the way, talking about public sculptures, I made this huge dinosaur in Leipzig; it was transported to Estonia, and at the moment I’m working with it, so it’s going to be bored into aluminium. It’s going to be outside, which I am very, very happy about. It will be different to the outside monuments we have here.

ŠP: Where will it be?

EK: It will be in Noblessner [an area in Tallinn], near to where the Kai Art Center is.

ŠP: So, a dinosaur by the sea.

EK: A dinosaur by the sea, and near the very hip and rich area. They need some reminders that they will die too.

ŠP: By the way, are you going to Basel yourself?

EK: Yes, I want to go, although I don’t have time to stay there for long, because I really have to do the EKKM show. I still have to slave to finish this snake man.

ŠP: Does the snake man have a title yet?

EK: It does, actually, Good, Bad and Ugly, because there are three of them.

Edith Karlson. Doomsday. 2017. View from exhibition “Do Come in, the Door is Open!”, Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, 2019. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo.

- October 2021

ŠP: Some time has passed since our conversation in June. You have finished your installation Good, Bad and Ugly, which was exhibited at the Art Basel main fair in the Statement section. It consisted of three life-size figures resembling transparent men’s suits. The suits were propped up by swarms of snakes, as well as many other snakes on the floor approaching the three figures. The walls that framed the sculptures were decorated with pieces of mirror in the form of eyes, watching the creepy yet beautiful scene with colourful snakes. If I understood it correctly, the work was an allegory for both fears and phobias, and healing. Now, looking back, have your thoughts about what this work represents changed? And did you get any interesting feedback from the visitors?

EK: This work took all my energy away. I have an opening on 29 October at EKKM. We will start to install it on 18 October, and there is still so much to be done. So much energy went into this Basel work, because it never went more easily. I am still affected by all this experience. It is a very fragile piece, it has to be very clean. And now I have to get back to the EKKM project. My brain is swollen (chuckles). I was hoping that when I went to Basel the tension would go away, that I would have this feeling of freedom now that it’s done. Unfortunately, that did not happen, because it was too intense. But you know, time will do the healing.

I was not up to communicating with visitors very much. The only time I did was when you saw me that evening interacting with buyers. I even warned the galleries that I would communicate with visitors only if it was really necessary. So I did not get any direct feedback. This work is packed with so many allegories and ways to look at it. If you are scared of snakes, then you freeze. You don’t go even near it. And then there are those reptile friends, who are like ‘Uuuu, what a beautiful snake!’ And then there are those who see everything as this complex thing. The snakes, the suits, the humans, the eyes. It depends on the person. You asked if the meaning of the work has changed, and I would say no, it’s still full of different metaphors, starting from the naked emperor’s clothes, this transparency. It has also been a bit therapeutic for me, as I was scared of all kinds of worms. I have been making dozens and dozens of snakes, which is very time-consuming work. The main problem when I was making this installation was my obsession with making it transparent. But in the end, I’m quite happy, as it came out the way I made my sketch. I never made this one-to-one work like I did with Basel. My works are usually like a journey, I never really know where I will end. I took up this challenge, and I did it. I think I will really have time to truly process it after the EKKM show opens.

Edith Karlson. Good, Bad, Ugly. 2021. View from Temnikova & Kasela gallery booth at Basel Art Fair. Photo by Justin Meekel

Edith Karlson. Good, Bad, Ugly. 2021. View from Temnikova & Kasela gallery booth at Basel Art Fair. Photo by Justin Meekel

ŠP: I like it when preparing for an art fair becomes an art project in itself, an exhibition or a new installation. You were in the Statement section, which at its core was also meant to stand out, to bring something different to the table. You did not sell all your works as one piece. People could buy each of the sculptures separately, as well as snakes. After one of the sculptures is sold, isn’t it a bit sad now that it’s split up?

EK: It’s very sad. I’m even a bit shocked. I was asked how I would like them to be sold. I never honestly thought anybody would buy them. I love this work, but that does not mean that others should love it. So when the gallery asked about selling them piece by piece, I said, yes, why not? Yesterday I was looking at the picture of the work again, and started to think, what will I do with two left-over sculptures. They’re now separated, like you said. I have to think about it now.

ŠP: Of course, I understand that sales sometimes do better or happen at all if works from a series or an installation can be sold separately.

EK: I just had this silly hope that if they get this one sculpture, they will eventually see that the sculpture misses his brothers. They will find the money to buy the others too. If I show them again, then it’ll be only one. I don’t like those even numbers.

ŠP: In the summer we were talking about how you used to have problems with symmetry, and that you decided that it’s okay that you don’t have it in your works. So every time something is a pair, whether it’s two or four, it becomes symmetrical.

EK: Yes, exactly.

ŠP: One can obviously see in your work an element of fear, as well as the allegory of a naked king who does not see that he is naked. But then one of the allegories encoded in the work is also the healing. You have already mentioned how this work was therapeutic for you. It started with feeding your friend’s snake.

EK: Yes, it took away that abstract fear which makes you despise those creatures or fear them. You have to deal with it, with all kinds of bad feelings and emotions.

ŠP: It’s a rather wild thought, but would you say that this work could also be about this weird fear that people have of the Covid vaccine?

EK: Yes, in a way it is. Someone is sowing weird thoughts in you, and you just go with it without analysing it.

ŠP: We met in Basel for a short time at the end of one of those long working days at the fair. You were chatting and photographing together with some clients. Could you describe a little your personal experience of being at this Basel fair Disneyland?

EK: I am the worst person for this kind of event. I am a slow person, so the format does not work for me at all. Which just makes me admire even more those people who come there and buy tickets. How do they orientate themselves there, and like this format which for me is like another universe? I think it’s like a job, and not so much like entertainment. It’s like a hard-core hobby. I was saying to one of the gallery people, Lilian, that taking your artist to an art fair is like taking them to the slaughterhouse (laughing). You really are out of your comfort zone, but if you take this very seriously as an artist, then you see it as your job to know what is going on, and how galleries work. I would suggest to everybody to go, then they would understand much better what galleries are doing.

ŠP: Would you say that it was also a learning experience?

EK: I have also watched how the Temnikova & Kasela Gallery works, as I have been to couple of fairs. So I knew a bit. But it’s different when it’s your own work being presented. Then you see it even more deeply. The logistics, every step that the gallery is taking, is a lot of work. So the understanding of the need for the gallery just deepens.

Edith Karlson. Drama is in your head I, from, exhibition “Dog Show” 2011. Photo by Riina Varol.

Edith Karlson. Family. 2019. View from exhibition “Do Come in, the Door is Open!”, Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo.

Edith Karlson. Vox Populi. 2020. Ceramics.

Edith Karlson. Vox Populi. 2020. Ceramics.