A stream of thoughts reconstructing recent events glides through the brain like sharpened blades. The cuts slice through the fabric of memory, striving to ensure that, in the future, the present will heal with scars from the sutures bridging the gaps. Never forget, I think, as if the cuts weren’t enough: blood also flows from the wound at my temple, caused by the bullet of an intense voluntarily inflicted experience. Yet the very word never, implying no time and encompassing non-being, projects the inevitability of forgetting.

In this introduction addressed to readers, I weave hints of my personal experiences into the fabric of collective memory, as fine as capillaries. A similar process unfolds at the Drifts gallery, where the younger-generation artist Morta Jonynaitė presents her solo exhibition ‘Light Rain with Big Drops’. Interpreted, reflected upon, or simply consumed as visual imagery by viewers, the artist’s work, layering references to private life and widely recognised phenomena in the form of memories and reflections, flow into the organism of collective memory. The interweaving of personal and collective memory in a single fabric serves as the central theme of this exhibition, inspired by the book The Years by the French writer Annie Ernaux.

Morta Jonynaitė, Chimeros, 2024, Diptych,Cotton, knotting, weaving, crocheting, 100 x 60 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

The exhibition commentary, written by the curator Paulius Andriuškevičius, opens with words from this very book: ‘At these moments she thinks that her life could be drawn as two intersecting lines: one horizontal, which charts everything that has happened to her, everything she’s seen or heard at every instant, and the other vertical, with only a few images clinging to it, spiralling down into darkness.’ It is worth noting that this quote is chosen with remarkable precision in the context of Jonynaitė’s exhibition. The horizontal and vertical axes mentioned reference the artistic expression of the exhibited works, woven vertically and horizontally by interlacing threads. Simultaneously, Ernaux’s words evoke the narrative structure of blending two memories into one coherent whole.

Jonynaitė quite literally weaves her personal experience into the fabric of collective memory, where they find a place in the viewer’s own recollections. First and foremost, her works testify to the physically demanding labour required at the loom, where the textile objects are meticulously created. Later, on reading the accompanying text written by Jonynaitė, it becomes evident that her works encode memories of her daily life, travels, memorable moments, and similar experiences. However, no matter how many autobiographical details of the artist we might uncover, her objects are equally rich in fragments of collective memory. Jonynaitė continues the ancient weaving tradition connecting the past with the present. Her woven works incorporate decorative elements conceived by other creators, filtering pre-existing ideas through her personal lens. The titles of her pieces reference popular culture, mythology, and geographical landmarks. Furthermore, the exhibition is accompanied by a written narrative that hints at universal human experience and societal issues.

As I reflect on the fabric of two interwoven memories in Jonynaitė’s works and try to discern, through the quote from Ernaux, whether the horizontal axis represents personal memory or the vertical, I find myself contemplating the interplay between personal and collective memory. The horizontal axis described by Ernaux is threaded around the pronoun she, which, while referring to an individual, situates her within the grand narrative of history: amidst everything that has happened to her, what she has seen, what she has heard, every moment. The word everything resonates as a densely textured fabric, woven from actual things: facts, melodies recorded in the media, and images captured within. This resonates with my thoughts on how I can often remember the plots of films, series and books better than events from my own life, which, on rereading my journals, often surprise me. I can recite entire lyrics of songs that I didn’t write, but I can’t recall the words I spoke in important conversations. I know the dresses Emma Stone wore while accepting her Oscars, but I can’t remember what I wore on my first date. Thus, while I exist as an individual, I thrive in the persistent mire of events and phenomena surrounding me.

I identify the competition of memories not only in the dynamics of Jonynaitė’s works described above, but also in specific examples. On entering the gallery, I encounter the piece Pink Street Boys, whose silhouette reminds me of the ceremonial mantles worn by monarchs and priests in grand processions, symbolising luxury or spirituality. However, reading Jonynaitė’s narrative, I discover that the piece encodes the opposite: gritty bar and punk rock culture, along with memories of the smell of sweat and the artist’s battles with personal demons. This leads me to question which side of Jonynaitė’s work, the external or the internal, carries more weight. As a viewer, Pink Street Boys is visually intriguing to me, but the clear associations evoked by my initial impression quickly overshadow this sensation. At the same time, the silences in Jonynaitė’s personal story draw me in like a thread caught in a sewing machine, provoking an urge to know more. Who is the boxer who left marks on her body?

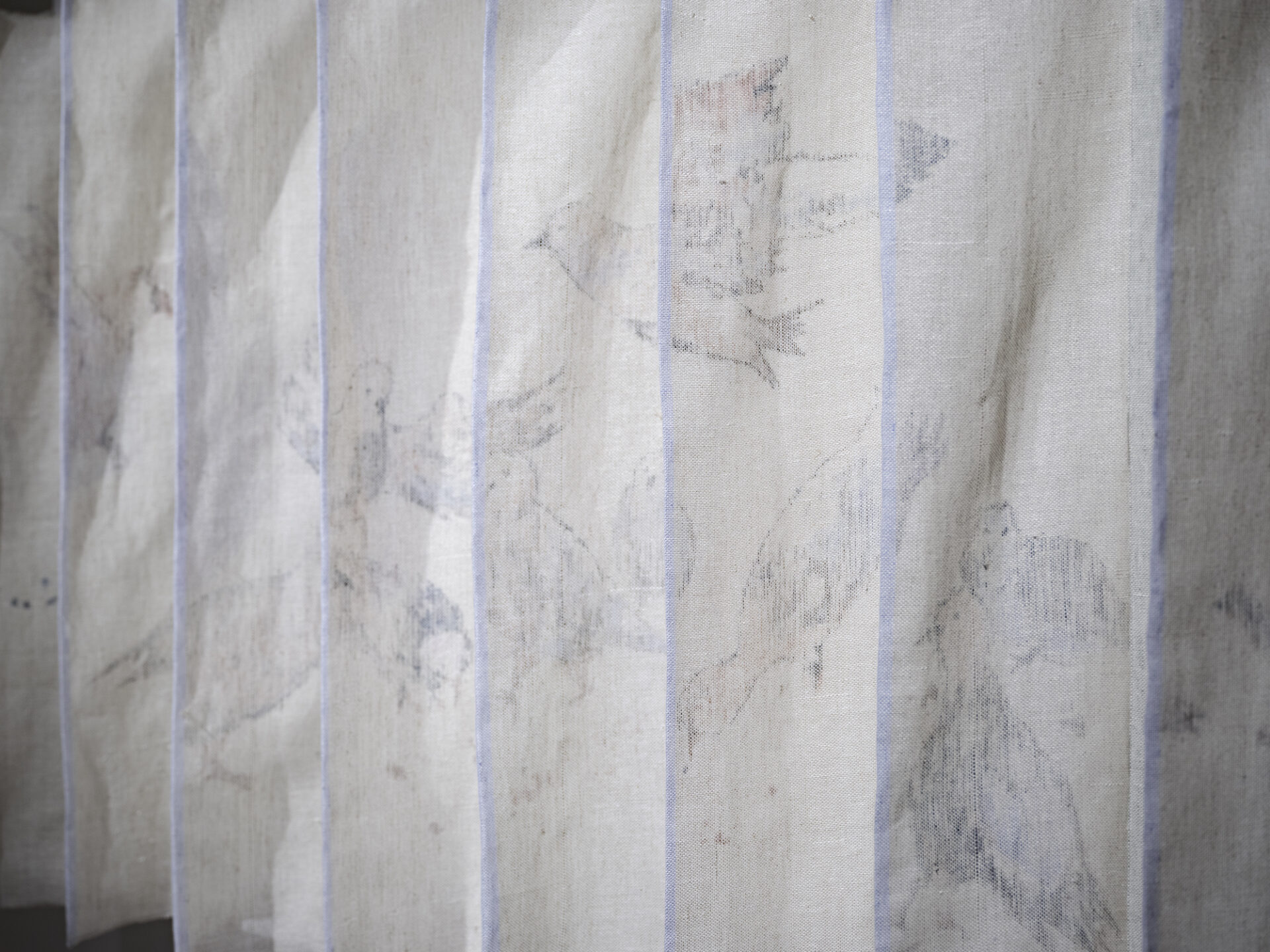

Morta Jonynaitė, Shed Skins, 2024, Triptych, Linen, cotton, hand weaving, sewing, wood carving, Variable dimensions. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Collective memory is often shaped by societal wounds and traumas. It is no surprise, then, that Jonynaitė draws attention to social issues in this exhibition. While observing the diptych Chimeras (though no matter how I look at it, I see the image of the mythical Greek creature Medusa depicted from the front and the back in the lacework), I gather from the title and the roaring folklorically stylised face that this piece represents dark forces. The screaming mouth, furrowed brows and dishevelled hair symbolise an outburst of anger, an emotional response to the unjust treatment of an individual. What specific behaviour this message addresses becomes clear in Jonynaitė’s narrative, which hints at the suppression of women’s freedom. Chimeras refers to trampled women’s rights: silencing, the denial of free will, degrading social status, and inflicted harm.

Another social issue reflected in the exhibition, which I discern in the piece 10 Minutes of Vilnius Silence, is marginalisation. Observing the work created using the anamorphic principle, where one angle reveals a reclining person and another a flock of pigeons, the complementary images remind me of the marginalised individuals I’ve seen in the station district. A drug addict overdosing, a reeking alcoholic, a battered thief: one of them lies unconscious on Chopin Street. This person, perhaps struggling with depression, haunted by life’s traumas and challenges that they were unable to overcome, probably leads a life as sombre as the sound of the Prelude in E Minor Op. 28 No 4. Yet few passers-by burden themselves with pondering the reasons why this individual has reached such a low point, or take action to change it.

The wounds and traumas that sow ideas uniting individuals in collective thought, eventually forming collective memory, have paved the way for movements such as feminism, social policies and protections. From this perspective, collective memory appears to have greater strength than personal memory. However, at the same time, I reflect on the fact that no collective memory could exist without the individual stories that happened to specific people, becoming their personal memories. This brings me back to the question: which holds more weight, the external world surrounding the individual or their internal world?

In the course of this article, I have already considered how I tend to remember movie plots and song lyrics better than my own experiences and spoken words. However, the reverse relationship between these memories is also intriguing. Songs often revive suppressed memories of specific individuals, or reconstruct sensations once felt, while movie plots transport me back to similar moments I’ve lived in the past. Such personal memories are revived through the recognition of shared human experiences, experiences that some of us reflect upon through creative work, and others in our thoughts while engaging in everyday tasks.

Morta Jonynaitė, Blissfully Unaware, 2024, Linen, watercolor, hand weaving, sewing,145x 153 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Jonynaitė’s work Blissfully Unaware resonated deeply with its sense of familiarity. The abstract landscape motif in the textile resembles a watercolour painting, its forms seemingly poured from stains made by wine and ink, exuding an expression of disappointment, nostalgia or longing. This impression is amplified by a sentence filled with regret in Jonynaitė’s accompanying text: ‘For four years, I lived entirely in memories and perhaps spent too much energy trying to keep them vivid.’ This piece reflects how the constant process of reworking thoughts unravels the fabric of reconstructed information thread by thread. As a result, wear and tear emerge, the silhouette’s shape alters, patterns fade, and decorative elements fall away. Here, I return to Ernaux’s words cited in the exhibition commentary about the vertical axis, where only a few images remain, plunging into the night. At least for myself, I interpret the vertical axis in the French writer’s book as pointing to the transient and constantly eroding nature of personal memory, where, over time, only individual threads hang loosely from the dismantled fabric. Yet no matter how tattered this structure may be, it remains an inseparable part of who we are.

The stream of thoughts reconstructing recent events glides through the brain like sharpened blades. The cuts slash through the fabric of memory, striving to mend the present into future scars where threads bind the ruptures. I will always remember, I think, as if the cuts weren’t enough, blood still trickles from a wound at my temple, the result of an intense experience voluntarily shot into my mind. The very word always, implying an enduring span of time and embodying existence, projects a certainty of remembrance.

At this moment, I’m not even sure whether this is the introduction or the conclusion of the text. Never forget or always remember. It could go either way, as I recall words that once echoed in the past. Yet only the unknowable future will reveal the quality and longevity of this reconstructed and reprocessed material. There will always be songs, films and well-trodden paths that transport us back to the past. Thus, perhaps collective and personal memory do not compete at all, but instead form a masterful balance, preserving stories.

The exhibition of work by Morta Jonynaitė ‘Light Rain with Big Drops’ is on view at the Drifts gallery until 28 December 2024.

Morta Jonynaitė, Departed, 2024, Cotton, wool, textile dyes, hand weaving, metal construction, 168 x 136 x 14 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Miglos str., 2024, Linen, cotton, textile dyes, hand weaving, sewing, wood carving, 245 x 360 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Chimeros, 2024, Diptych, Cotton, knotting, weaving, crocheting, 100 x 60 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Chimeros, 2024, Diptych, Cotton, knotting, weaving, crocheting, 100 x 60 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Shed Skins, 2024, Triptych, detail. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Harper’s Bazaar, 2024, Linen, viscose, lurex, hand weaving, sewing,39 x 51 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, Pink Street Boys, 2024,Cotton, wool, textile dyes, hand weaving, wooden construction, 172 x 116 x 25 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, 10 Minutes of Vilnius Silence, 2024, Linen, markers, hand weaving, sewing, 110 x 200 x 19 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, 10 Minutes of Vilnius Silence, 2024, Linen, markers, hand weaving, sewing, 110 x 200 x 19 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas

Morta Jonynaitė, 10 Minutes of Vilnius Silence, 2024, Linen, markers, hand weaving, sewing, 110 x 200 x 19 cm. Photo: Martynas Norvaišas