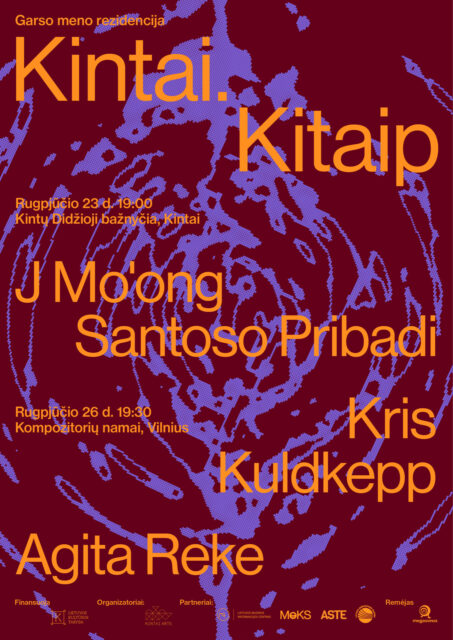

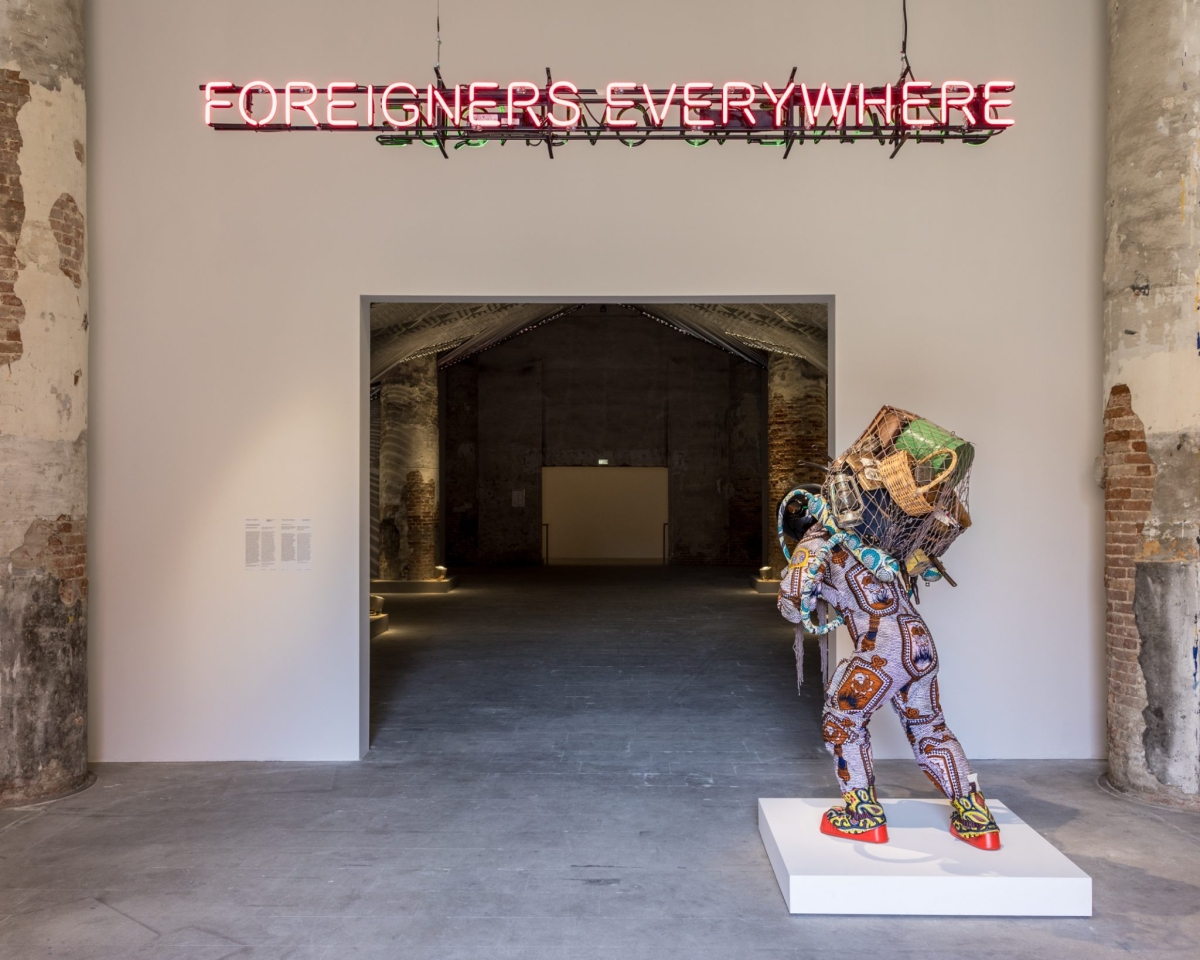

With a self-ironic nod towards the event’s colonial and nationalistic undertones, this year’s Venice Biennale is entitled ‘Foreigners Everywhere’. The main exhibition, curated by historically the first queer and Latin American Venice Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa, strives to bring to light marginalised practices. While provocatively raising questions about representation in the art world, the creative direction of this year’s Biennale is sticking to rather tired and overused methods of curation, and sometimes enforces exclusion under the pretence of inclusion. So where does the Baltic region fit into this landscape? The short answer is nowhere. But it’s not necessarily bad news.

One of the shortcomings of ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ lies in its attempt to lump together a diverse array of practices under the label ‘outsider’, as if queer, indigenous and artists from the Global South all fit into the same box. This approach exacerbates the very issue it seeks to address, by failing to celebrate artists’ unique characteristics, and instead perpetuating their marginalisation. Therefore, this year it’s particularly gratifying to see individual artists use the national pavilion’s scale to convey their unique visual train of thought, rather than to create a sanitised, politically correct collective voice to inclusively cater for everyone, but ultimately speak for no one in particular. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ message. Moreover, ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, featuring 331 artists, most of whom are deceased, felt like a disappointing echo of Cecilia Alemani’s ‘Milk of Dreams’ at the 2022 Venice Biennale, where the curator strikingly paired historically overlooked artists’ works with contemporary artists.

‘Foreigners Everywhere’, 60th Venice Biennale, 2024. Photo: Marco Zorzanello. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

Despite the best efforts, in the name of inclusion, Pedrosa has respectfully excluded a significant number of European ‘outsiders’. It begs the question: who is ‘foreign’ enough, in defiance of mainstream Western codes, to secure the artistic inclusion of this year’s biennale? Viewed through the lens of Baltic origins, shaped by a post-Soviet legacy that has always felt somewhat alien and out of sync with dominant Western cultural narratives, this biennale might just prompt a reevaluation of what it means to be a ‘true outsider’. Referencing a question the Latvian art historian Megija Mīlberga put to Adriano Pedrosa when the curator was giving a guest lecture at NYU: ‘Why were no artists from Ukraine included in an exhibition focused on the migrant and refugee experience?’ Pedrosa replied with a counter-question: ‘Why Ukraine? There are many other countries whose artists are not represented, and I am more concerned about that than about Ukraine specifically. For instance, I am more worried about the lack of representation of artists from Senegal or Thailand.’[1] This brings to mind the ‘reverse mermaid’ sculptures by the Estonian artist Edith Karlson, because it seems that we’re ‘neither fish, nor flesh, nor good red herring’.

In this year’s biennale, for us in the Baltic, being ‘neither here nor there’ might be precisely the point. In stark contrast to the main exhibition, the Baltic pavilions this year present a delightful twist, eschewing the ethno-trend bandwagon in favour of their own distinctive rhythm. Our idiosyncratic region, which has historically been a ‘hit or miss’ affair in Venice, presents something refreshingly different this year. The three pavilions vividly and powerfully showcase distinct artist practices, steering clear of socio-politically overloaded, calculated and worn-out narratives that often overshadow individual artistic practices.

Inflammatory foreigners

Appearing more aligned with the otherworldly ambiance of the previous Biennale’s ‘Milk of Dreams’ than the ethnographical scope of ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, the Lithuanian artist duo Pakui Hardware and the postwar avant-garde artist Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė present a stunning union of old and new worlds. This exhibition is curated by Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia. The feverishly pulsating pavilion, entitled ‘Inflammation’, is off-site in the Chiesa di Sant’Antonin, a church hosting an exhibition for the very first time. It is a large-scale installation, which the artists describe as ‘more of a state of mind or body than a show’.[2] This year’s Lithuanian pavilion reprises an exhibition initially shown at the Museum of Applied Arts and Design in Vilnius in Lithuania nestled within a pseudo-Renaissance architectural setting. While the installation remains basically the same, the shift to the church’s architecture lends it a slightly different mood.

Pakui Hardware and Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Inflammation, 2024. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda.

Pakui Hardware’s usual focus on the plasticity of bodies and their interplay with medicine and technology finds a layered conversation with the paintings of the Lithuanian artist Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, who once dissected the Soviet Union period’s techno-utopian medical dreams. The installation evokes an oversize nervous system, revealing the explosive effects of societal structures on both its natural and synthetic counterparts. In a nightmarishly mesmerising scenography, the sacral architectural backdrop of Chiesa di Sant’Antonin forms a haunting support for this apocalyptic narrative, conjuring up catastrophic visions of our future.

The exhibition architecture is created by the Lithuanian architect duo Petras Išora-Lozuraitis and Ona Lozuraitytė-Išorė, whose set-up captures the fragility and volatility of our times. The landscape is formed with plastic dunes, born from the plastic recycling process, each ridge and valley a testament to our synthetic future. Rožanskaitė’s work provides a counterpoint to Pakui Hardware’s techno-organism of fused aluminium and glass sculptures by weaving a human thread into this cosmic, dystopian tableau. Her paintings evoke bodily horror, portraying individuals ensnared in hospital beds, enveloped in medical unease and physical agony. Rožanskaitė employs saturated colour combinations and distinct contours, creating a contrast in her paintings that, in this setting, seems to radiate with a surreal, almost radioactive glow. As beams of light strike Pakui Hardware’s glass sculptures, they come alive, igniting in a fiery effect. This interplay creates a resonant harmony between the painting and the installation, a play of light and colour that intensifies the exhibition’s eerie mood.

Pakui Hardware and Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, Inflammation, 2024. Lithuanian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda.

One of the main references for the exhibition is Rupa Marya and Raj Patel’s book Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice (2021). They discuss chronic inflammation as the legacy of everything inscribed in your body, not just in your lifetime, but through the lives of our ancestors. Inflammation, a response to unhealthy conditions, reflects accumulated traumas and the history of oppression. Accordingly, extending this idea, we see inflammation’s effects not only on human health, but on communities, social structures, and the planet itself. From this perspective, for the artists, the theme of the exhibition, namely ‘foreigners’, are the ‘foreign bodies’, the inflammatory particles causing the infection. If we consider it, the earth is inflamed, and the culprits are us humans ourselves. It is a rather unexpectedly unifying exhibition narrative: our collective misdeeds are equalising us as a race, transcending ethnicity, religion, gender and sexuality.

The dawn of mankind

Another distinct site-specific installation in sacral architecture evoking post-human themes is presented by the Estonian Pavilion. Entitled Hora lupi and created by the Estonian artist Edith Karlson, it is located in the crumbling 18th-century Chiesa di Santa Maria delle Penitenti. As the exhibition text informs us, the title Hora lupi means ‘hour of the wolf’. It ‘refers to a mythical time before dawn, when things arise and disappear, an hour of deep darkness, but also of transformation’, as well as the time of night, when most births and deaths are believed to occur. The installation features over 300 sculptures crafted from a diverse array of materials, including clay, concrete, jasmonite, terracotta, and more.

Edith Karlson, ‘Hora lupi’, 2024. Estonian pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art. Photo: Anu Vahtra.

Entering the pavilion through its dusty façade, you are greeted by a hauntingly surreal sight: an altar flanked by massive concrete giants grappling with a serpentine creature. The sculptures are so seamlessly incorporated, it feels as if these eerie figures, locked in eternal struggle, were built together with the church itself. As you proceed deeper into the installation, a gaping hole in the floor reveals the Venice canal seeping in. Right next to this aqueous breach lie three reversed mermaid figures, their human torsos incongruously capped with fish heads and extending into fish tails, and the site is accompanied by a ghostly ethereal tune. Possibly, a sardonic nod to Venice’s struggle against the encroaching waters.

Edith Karlson, ‘Hora lupi’, 2024. Estonian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art. Photo: Anu Vahtra.

Passing by three weeping women, you enter a ‘future-memorial’ room, where human masks, hand-crafted clay self-portraits, made by people from the artist’s circle, line the walls. These are references to 14th-century terracotta sculptures from St John’s Church in Tartu, and seem to come straight out of the Hall of Faces from Game of Thrones. There is also a cabinet of horrors, brimming with found animal skulls transformed into otherworldly relics by a slick enamel glaze, accompanied by terracotta monster sculptures made by the artist’s son. Karlson has created a beautifully strange confluence of stark reality and fantasy, where the present flows into the past with a ghostly, unsettling grace.

Edith Karlson, ‘Hora lupi’, 2024. Estonian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art. Photo: Anu Vahtra.

The architecture has been the artist’s primary inspiration, merging so seamlessly with the works that they appear to grow from the church’s very foundations. ‘Sometimes it’s maybe even hard to understand where the church begins and my work ends,’[3] Karlson told Artsy. The church becomes a metaphor for the crumbling state of mankind, a world in decline, and our fleeting grasp of spirituality and morality. In a way, Edith Karlson shares a thread of this post-human world setting with Pakui Hardware, yet with completely different visual story-telling tools. Where Pakui Hardware speculates on potential futures of a world continuing down its current path, Karlson uses animal forms and anthropomorphic figures to symbolise human nature’s primal impulses. Her work seems to suggest these very impulses could be what ultimately lead us to those dystopian scenarios. The installation carries a palpable sense of doom and mourning, yet it is imbued with an unsettling divinity and strange excitement. There is a recognition that the old world has vanished, and it is all right to weep. Yet in the midst of this sorrow, there is a subtle sense of something new taking shape.

Paintings that refuse to sit still

If any pavilion could embody a quintessential Latvian personality trait, it is Amanda Ziemele’s installation representing the Latvian Pavilion, entitled O day and night, but this is wondrous strange … and therefore as a stranger give it welcome. A hurried visitor might easily overlook it, as the artworks are deliberately introverted, subtly tucked away from the casual gaze of those passing through the Arsenale. To fully engage with the exposition, one must interact with it: walk around, peek inside, and allow it to reveal itself. Ziemele embraces the inversion of colours, presenting the outside as the inside. She challenges the notion that there is a ‘wrong’ side to artwork, suggesting instead that both the interior and the exterior of a house, or an artwork, are equally valid. Amanda Ziemele’s ‘creatures’ are shy only at first glance, and reveal their ‘true colours’ when one gets ‘a well-rounded view’.

Amanda Ziemele, ‘O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as a stranger give it welcome’, 2024. Latvian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Culture project agency INDIE. 2024. Photo: Līga Spunde.

The large-scale paintings showcase unique architectural qualities. Functioning as vibrant entities, each with its own mood, they appear to move, wrap, fold and stretch, creating a dynamic interplay with space. They can envelop the viewer, offering a form of shelter, shell or sanctuary, or engage with them in various other ways. A new cosmology emerges from Amanda Ziemele’s distinctly unique style, one which is always unmistakably bearing her creative signature. These ‘curious giants’, as the exhibition architect Niklāvs Paegle dubs them, are anything but static: ‘Newcomers to this world, trying to exist.’ Ziemele emancipates the painting, eliminating the concepts of background, front and back. The environment itself transforms into the artwork, forming a new, collaborative landscape where every element of the painting participates in a dynamic interplay. Even if the backs of the paintings mimic the windowpanes of the Arsenale, they are not tied to a place, or even a pose. These works will adapt effortlessly to different environments, folding into various shapes and forming new landscapes.

Amanda Ziemele, ‘O day and night, but this is wondrous strange… and therefore as a stranger give it welcome’, 2024. Latvian Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Culture project agency INDIE. 2024. Photo: Līga Spunde.

Ziemele’s installation is following the Shakespearian thread from Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 novella Flatland. A Romance of Many Dimensions, published under the pseudonym A Square. This classic science fiction work aims to stretch readers’ imagination beyond their conventional ‘dimensional biases’. Through strange occurrences that bring him into contact with a host of geometric forms, Square experiences Spaceland (three dimensions), Lineland (one dimension), and Pointland (no dimensions). As he contemplates the audacious possibility of a fourth dimension, a notion so radical it threatens to shatter his two-dimensional existence, he is swiftly ushered back to his flat, familiar plane. For now, Amanda Ziemele remains unreturned to flatland, and can safely proceed the daring leaps beyond the confines of a two-dimensional painting. The installation is offering an insight into a multi-dimensional world, where the dimensions of each of the objects are ‘variable depending on the point of view.’[4]

The curator Adam Budak fervently contextualises Amanda Ziemele’s abstract painterly process through Shakespearean meta aspects. This undoubtedly adds layers to Ziemele’s abstractionism, and further extends the notion of her boundary-defying painting forms. However, it is hard to forget that Budak delivered a 20-minute speech at the pavilion’s opening, while the artist herself may have spoken for two minutes. Therefore, regarding the curatorial framework of the exhibition, there’s a nagging suspicion that also here are proportions that might be somewhat askew. Reading the exhibition text, it is easy to get tangled in this curatorial thread, blurring the line between the artist’s voice and the wishes of the curatorial eloquence.

***

If one is searching for a unifying thread in the Baltic pavilions, one would be hard-pressed to find one, since their differences are more pronounced than their similarities. Yet if a collective idea must be discerned, all three have expressed an unwritten mutual agreement that a new order must (or inevitably will) take place. When it comes to the Venice Biennale’s self-conscious theme of decolonising biennales, these pavilions seem blissfully indifferent. They might, however, offer a few hints about what happens when you try to reinvent the wheel with a relic of a framework. Perhaps it will: a) cause the entire concept to crumble like an old church; b) demand the presence of multi-dimensional out-of-this-world entities; or c) require full-blown inflammation to sweat out the problem before anything can be done.

[1] M. Mīlberga, Māksla un sazāļoti tīģeri, Satori, 2024: https://satori.lv/article/maksla-un-sazaloti-tigeri.

[2] Pakui Hardware on representing Lithuania at the 60th Venice Biennale: https://artreview.com/pakui-hardware-on-representing-lithuania-at-the-60th-venice-biennale/

[3] Jameson Johnson, Casey Lesser, The 10 Best National Pavilions at the 2024 Venice Biennale, Artsy: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-10-best-national-pavilions-60th-venice-biennale

[4] Dimension indications in the exhibition map of Amanda Ziemele’s installation.