Breaking through. The base and the landscape are, in fact, taken hostage together. Boundaries fade, the contours of bodies slacken. Do I have to choose, or can I accept a hybrid of both? Boundaries, thresholds, essences, and elements are sliding, upsetting established systems.

Excerpt from “What’s Left” by Alexis Brancaz in the zine Extracted Values: Ecopoetics vs. Ecopolitics, LCCA Summer School Postsocialist Ecologies

“No, he will not recognize. He won’t. He can’t do it!” I mumbled anxiously as I refreshed the news. He did. Recognizing the independence of the proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics meant Russian troops at Ukrainian borders could attack any day now. It took three days for the full-scale invasion to begin. Since then, many institutions in Europe have undergone a paradigm shift. Or, at least, a reality check. War in Ukraine, with its brutal destruction of cultural heritage and civilian infrastructure, among other things, brought the consolidating role of art to the foreground.

Considering that no war is ever a mere territorial conflict and that Russia’s imperialistic rhetoric, against all odds, has an influence on particular publics, the art community should attempt to be responsible for re-channeling the discourse. During one of the public talks at Survival Kit 13 in Riga, Vasyl Cherepanyn, head of the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC) in Kyiv, put it plainly: to protect the values a culture stands for, institutions must not hesitate to trespass their boundaries. If they rely too much on art for art’s sake and forget about political involvement, the battle might soon be lost.

Cultural and civic organizations in the Baltic States are going to great lengths to assist the ongoing struggle, and to document and reflect upon it. Here, solidarity with Ukraine is particularly heartfelt because it is informed by the experience of several occupations. One of the vicious colonial narratives transmitted by Russian propaganda is that Ukrainian sovereignty is “artificial.” This is alarming for countries of the former Soviet bloc, as the same rhetoric could be weaponized against them. In fact, following the annexation of Crimea and the first flashes of war in Donbas, in 2016, the BBC already played out the ridiculous “People’s Republic” scenario—when an unbelievably high percentage of the Russian-speaking population in a given region decides to separate from the rest of the country under Russia’s protectorate—in Latvia.

In an episode of the television show This World, “World War Three: Inside the War Room” (2016), the action unfolds in Daugavpils, the second largest city in Latvia, in the Latgale region. Some may disregard the film as mere speculation, but it posits a significant problem. The film puts fictitious British masterminds in the spotlight. They quarrel to find the best strategy to outplay the goon from the Russian military command without provoking him—or he will push the button. A USA security advisor occasionally appears on screen. Her arrogant remarks fuel the heated debate where Latvian national representatives are hardly even mentioned. Latvia seems to be an arbitrary background. Indeed, Latvia has a long border with Russia, and Russian speakers comprise almost half of Daugavpils’s population. Apparently, that was enough for the simulation. The trick, however, is that this simulation is just a slightly altered version of the same colonial narrative where a country is considered only in relation to a greater power—be it USSR, Russia, or NATO—and is thus stripped of any agency.

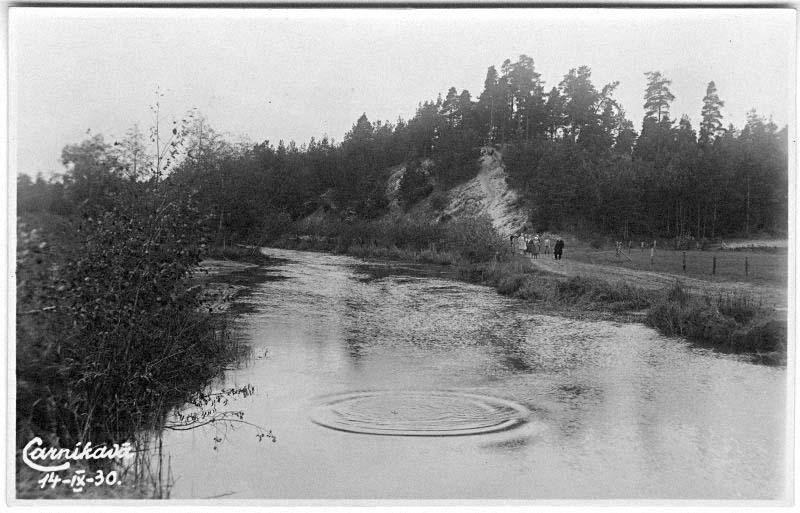

Gauja River mouth with coastal dune forests. 1930. Photo: National Library of Latvia.

Khrushchyovkas and decaying industrial infrastructure are the signature traits of post-Soviet landscapes. They make numerous locations in Eastern Europe interchangeable for Western filmmakers. What can this heritage tell us? In Latvia, intense industrialization and collectivization of agriculture happened against the backdrop of the brutal elimination of the national partisan movement and mass deportations of 1949, known as Operation Priboi. Around 42,000 people were sent to Siberia, and together with Estonian and Lithuanian citizens, the number of victims exceeded 94,000.[1] Territories were repopulated by Soviet citizens loyal to the regime. New factories welcomed workers from remote republics. By 1960, the population of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have grown by more than 217,000.

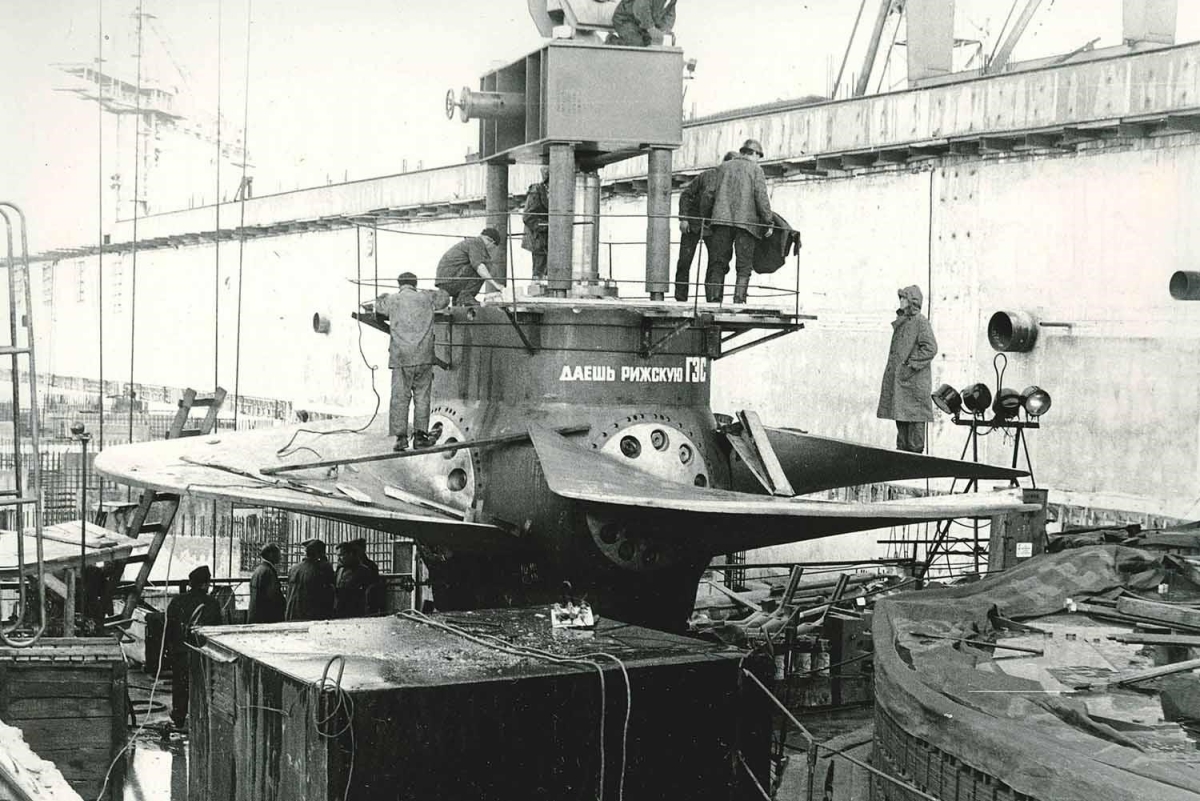

Demographic alterations were also accompanied by environmental exhaustion that drastically changed local landscapes and ecosystems. In 1986, thanks to Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, the public became aware of some government plans, including a new hydroelectric power plant project on Latvia’s largest river, the Daugava, and a decision to build a subway in Riga.[2] Both could have resulted in irreversible destruction of the local landscape and historical heritage. The media encouraged the public to oppose these decisions. Resonant protests served as an impetus for the formation of the Environmental Protection Club in February 1987. By the end of the decade, it became one of the most influential mass movements in the region and began to make demands for the restoration of the country’s independence.

With the emergence of the Republic of Latvia, residents who had relocated here during the Soviet era, as well as their descendants, could receive citizenship through naturalization. This procedure required passing a Latvian language proficiency test, a history exam, and memorizing the national anthem. But not everyone bothered. In 2022, there are now more than 182,000 non-citizens in Latvia, approximately two thirds of whom stated their nationality as “Russian” during the census.[3]

When Russia invaded Ukraine, everyone was afraid history would go in reverse. But where exactly? Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many of its former states—those that gained sovereignty and those still part of contemporary Russia—remained tied up in previously established colonial dependencies. They inform political agendas, civic structures, and local cultural identities but are often masked as “traditions,” “nature’s order,” or “historical justice.” At the snap of a finger, such narratives can be weaponized to justify military atrocities and horrendous violence. However, language can refute vicious imperialistic tales. Contemporary art mediates the discourse.

Valmiera Glass Fiber Factory interior and employees. 1975. Photo: National Library of Latvia.

The Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga reacted to the war in Ukraine in a multifaceted way. In March, they collaborated with the Museum of the History of Medicine on a series of participatory workshops, where together with artists, visitors could study and practice various forms of activism. People engaged in critical discussion, shared their anxieties, and formed new bonds while making protest banners—this project aimed to strengthen the community and increase public awareness. The Museum of the History of Medicine is located right opposite the Russian Embassy in Riga on a recently renamed Ukraine Independence Street. In September, the workshop series continued with practical sessions on crisis response skills. The program on emergency actions was developed together with the Latvian Ministry of Defense. Parts were integrated into the urban landscape as posters illustrated by comic artists from kuš!

A primary survival skill is being able to make sense of one’s surroundings. It may not always be easy in an area haunted by the ghosts of the *Post-Soviet*, yet, the LCCA tackles this problem as part of the transnational, interdisciplinary project From Complicated Pasts towards Shared Futures. A joint project between the LCCA in Riga, the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, OFF-Biennale in Budapest, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, and Malmö Art Museum, it strives to prevent hostility against underrepresented groups of European society, revealing the entanglements of disproportionate power relations, voicing how they influence the current state of affairs, and searching for meaningful ways and delicate strategies to shape a non-oppressive future.

In mid-March, during an online discussion about the political emancipation of artistic practices in Ukraine, I met Ieva Astahovska, a scholar, art critic, and curator at the LCCA. She moderated the event, which was part of a long-term project Astahovska was leading with her colleague Linda Kaljundi (KUMU, Estonia): Reflecting Post-Socialism through Post-Colonialism in the Baltics. The project started in 2020, touching upon notions of environmentalism, industrial heritage, ecofeminism, and decoloniality. I started following along when the program pivoted to the war in Ukraine as the project was coming to an end. Curators invited fellow art workers and researchers to provide a comprehensive outlook on contemporary Ukrainian culture and the ways in which it reflects on, and to some extent influences, societal shifts today.

One particular presentation stuck with me. It was an artist talk by Lada Nakonechna. In her work, she investigates the internal complexities of verbal and sonic structures and their subtle dictates. In Disciplined Vision (2021), Nakonechna meticulously studied the visual regime established by Socialist Realism. Socialist Realism was long considered the only officially acceptable style in the USSR and thus its ideological implications were disseminated widely across republics, with particular nuances of indigenous cultures either erased or blurred, exoticized or turned into decorative features. This not only influenced aesthetic habits and expectations but also constructed perceptions of history and national identities. Disciplined Vision points out these traps and subverts the stifling visual code of Ukrainian landscape painting, at times violently reducing it to abstraction or excluding and switching its key elements.[4] The artist provided a lens for a decolonial gaze on habitual sceneries.

Tractor. Seda Peat works. Original custodian: Rita Meluškāne. Photo: National Library of Latvia.

In Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving? Caitlin DeSilvey problematized the mechanisms of remembering:

We live in a world dense with things left behind by those who came before us, but we only single out some of these things for our attention and care. We ask certain buildings, objects, and landscapes to function as mnemonic devices, to remember the pasts that produced them, and to make these pasts available for our contemplation and concern. … Intervention and treatment aim to protect things from outright destruction or neglect as well as more indirect processes of erosion, weathering, decay, and decomposition. But what happens if we choose not to intervene? Can we uncouple the work of memory from the burden of material stasis? What possibilities emerge when change is embraced rather than resisted?[5]

This line of thinking was tangible throughout further research Astahovska facilitated on postcolonialism in the Baltics. In cooperation with colleagues, who participated in the discursive project mentioned above, Astahovska curated the annual LCCA summer school titled Postsocialist Ecologies. It was an intense five-day program oriented toward art practitioners, researchers, scholars, and critics. Conclusions and inspirations accumulated throughout the research period were then elaborated in a group exhibition, where postsocialist ecologies transitioned to the decolonial.

Since 2014, the LCCA summer schools have taken place annually in different regions of Latvia. The multifaceted program immerses participants in the complexities of current events with great precision. Participants dive into theory and creative work at a pace that can well compare to a decent academic semester. Study is in an egalitarian and participatory mode: while lectures and workshops are delivered by researchers, artists, and critics, people from the same fields comprise the audience.

In 2022 the summer school took place in August and sought to find a language for voicing local environmental concerns, build meaningful coalitions with publics outside the art world, and establish kinships beyond biological compatibility. Special attention was given to creative collaboration to emphasize the importance of shared experiences and experiments that could embody the ecological condition of interdependency. Participants were encouraged to develop a free-format artwork on any of the given topics: ecologies and gender, decoloniality in the Baltics and Eastern Europe, ecopoetics vs. ecopolitics, and everyday ecologies and Valmiera city.

I joined the decoloniality group with great enthusiasm and impostor syndrome—as a student with no artistic background, I was anxious about not being able to contribute. The fear faded away as soon as conversations actually started. Since tutors and participants had diverse backgrounds, the atmosphere turned out to be welcoming and ignited curiosity. John Grzinich, a visiting Associate Professor at the Estonian Academy of Arts, who was invited to give a talk on sensory explorations of Anthropocene landscapes, described it as follows: “The range of issues concerning social and political ecologies is broad. While many of these seem tangible on paper, matters become much more complex and ‘organic’ and take their own form when a group of people come together and start sharing their experiences and interests.” Grzinich went on to explain:

The emergence of the primacy of ecological concerns in recent years often challenges and contradicts the now “traditional” enlightenment-modernist conceptions of art. Finding ways to articulate and discuss colonialist and extractivist tendencies embedded within art and culture helps to open up new (and rediscover older) ways of thinking and working. I try not to see myself and my practice as a singular fixed entity but rather as one person among many who can cultivate more intuitive and receptive sets of habits and methods that allow relevant “creative” responses to the conditions at hand, be they personal, social, or political. Therefore, I saw the event less as a “school” and rather as a temporary cluster or node in an evolving network of researchers and practitioners who came together to share knowledge and information through various activities, be they talks, walks, presentations, dinners, or swimming.

The summer school took place at the yet-to-be-restored Kurtuve Art Center in Valmiera, in the Vidzeme region in north-east Latvia. The city has a complicated history—it has been razed by plague, fires, and wars over twelve times—and is today striving to be a modern industrial hub. The last major reconstructions happened here after World War II, in the 1950s, so the post-Soviet legacy lives on in urban planning. In the 1960s, while local manufacturers were the benchmark for the entire Soviet Union, many young people were leaving Valmiera for good, despite flourishing industry. The lack of housing, childcare, and opportunities for personal growth did not accommodate communist dreams. This gradual disenchantment is felt in the conversations in The Girls of Valmiera (1970), a witty documentary by Ivars Seleckis.

Nowadays, Valmiera’s municipal identity is somewhat rooted in the industries of the past. A label accompanying one public art object in the Bachelor Park said Valmiera’s character is distinguished by rationality and pragmatism. An example didn’t take long to appear: one local metal-processing company recently signed a contract with NATO. It is a significant investment for the municipal economy, which will ensure infrastructural development. Logistic networks in the city ask for some adjustments: a road to the facility I just mentioned goes through residential areas and kindergartens. Needless to say, it is not safe and quite inconvenient. During a city tour, our guide, a municipality representative, said the new route would bypass the center. Then, suddenly, she pointed to the trees on the roadside and said unwittingly, “These will be cut down, and an extra line will be laid here to unload the traffic.” Someone then asked, “Isn’t there any other way to do that without cutting the trees?” She answered, “To bypass the kindergartens and decrease pollution in the center, we had to find a compromise. The trees are dying anyway.” Participants looked at each other in bewilderment—that didn’t sound eco-friendly.

The notion of compromise popped up again as we gathered for dinner when the tour ended. Posters in Jauna Saule [New Sun] café gave food for thought, quoting Ludwig Erhard: Kompromiss ir māksla sadalīt kūku tā, lai katrs domātu, ka vinš ir dabūjis lielāko gabalu [A compromise is the art of dividing a cake in such a way that everyone believes he has the biggest piece]. I find this metaphor bitter—what if the enemy has an appetite for your motherland?[6]

Since the opening of the 2011 Russian gas pipeline, the Nord Stream has played a significant role in what resulted in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Before the project was launched, Ukraine used to be a transit zone for Russian oil and gas on its way to Western Europe. The Nord Stream allowed the parties to abandon the outdated Soviet infrastructure, increasing revenue and supply. An exhaustive view on this matter was given during an online talk with Ukrainian filmmaker Oleksiy Radinski, who thoroughly investigated the economic and political rationale behind the Nord Stream and described the ecological hazard it posed.[7] He further compiled these findings into a documentary film, sourcing footage from the official website of Nord Stream AG. At the time of the talk and film screening at the summer school, it was a work in progress. Now, following attacks on both the Nord Stream-1 and Nord Stream-2 pipelines, Radinski’s film will perhaps have the most epic ending.

Transitions from post-Soviet to neoliberal not only fuel corruption and disproportionate wealth among the elites but produce enormous garbage flows, which are often pushed to the peripheries. The summer school program included visiting ZAAO, a waste management facility in the North Vidzeme region. After a bumpy bus ride, we disembarked at a scenic place. In front of us was a neat education center furnished in beige wood. Behind were hills of shredded plastic, fiber, and tires with sunflowers growing out of them against all odds. The location was selected because of the sparse population in the area: since only a few people lived here, only a few opposed the project. Those who did, however, are now compensated: waste utilization provides cheap electricity. Besides, ZAAO covers medical insurance for the residents—a perk of great significance, considering the hazardous emissions. As the facility representative described the daily operations, he admitted its sustainability as a rare enterprise of this kind was problematic. Not only will the trash buried in the ground probably never decompose, before ending up at ZAAO, it travels across the country by trucks. However, the demand for the services is high.

While manufacturing industries and consumerist economies indulge in greenwashing, the amount of waste they produce outweighs any individual habit. For mass pollution to slow down, at least fractionally, downscaling should be imposed on the structural level… A jaded request. Puzzled, we looked at our linen tote bags, sighed, and went back to the bus. A flock of storks rose from the trash pile and soared into the air. Birds feed here but often choke on small plastic pieces. Protective nets are intended to keep small animals and birds away, but they still sneak in and feast on this waste cornucopia.

Even though items harvested from the wasteland are rarely nutritious, exceptions exist. Certain organisms sprout from lifeless substrates to build new ecosystems—humans could learn from them and come up with trickster moves necessary for discursive influence. Diana Lelonek, a Warsaw-based artist and photographer, advocates for supporting this non-human labor and deliberately does so herself. At the summer school, she described how an amber-like berry can revive a land exhausted from coal mining. In Seaberry Slagheap (from 2018), Lelonek suggested re-channeling the Konin Coalfield area’s economic potential by developing a line of wild, locally grown sea buckthorn products, thus cultivating a plant and drawing public awareness to the environmental condition of the region through delicious food. Once Lelonek even sneaked into the COP 24 Climate Conference in Katowice with jars of homemade seaberry jam, the plant paving the way to the political arena. As the project developed, it grew from artistic research into a determined community initiative. After all, that was its main purpose. Lelonek aimed to inform and inspire local residents to be mindful of their surroundings and approach them with care.[8]

In 2002, American literary scholar Bruce Robbins defined the concept of the sweatshop sublime, whose mechanism is triggered when we realize we belong to the global world of capital and labor. Robbins argues that the aesthetic sense engendered by globalization is based on an attempt to reconcile the situation of consumerism with those myriad interconnected hands and minds that produce the objects of our consumption under conditions of rigid exploitation. This sudden and shocking realization of the global dimension of existence and its cultural and economic implications are defined through the notion of the sweatshop. The latter often leads to stagnation, apathy, and the impossibility of an individual manifesting their epistemological capacities or sociopolitical activism. The discovery of this dimension in the singular, everyday, intimate experience world leads to a sense of one’s infirmity, weakness, and inertia.[9]

Madina Tlostanova, professor of postcolonial feminisms at Linköping University, Sweden, suggested a life-affirming alternative to the sweatshop sublime: the decolonial sublime. According to Tlostanova, global coloniality and our belonging to it in different capacities—from objects to subjects, from critics to accomplices, and those who consciously try to dissociate themselves—are the driving force of sublimation. Moreover, unlike sweatshop aesthetics, the decolonial sublime does not lead to apathy and stagnation. It does not necessarily move us toward political activism, however, but it certainly leads to significant shifts in the ways we interpret the world and relate to others. Most elements of the sublime are present in decolonial aesthesis. It returns dignity to subjects and liberates their consciousness, creativity, imagination, and being—not from natural forces but from the constraints of modernity/coloniality.[10] The summer school provided an overview of both the sweatshop and the decolonial sublime by paying attention to obsolete infrastructures and how they could be unexpectedly revived, either by necessity (the unacceptability of Russian fossil fuels) or by artistic imagination.

Once most of the suggested readings were reviewed, the time came to present our creative projects. Before everyone left, fellows who focused on ecologies and gender (Anne Sauka, Jana Kukaine, Maija Pavlova, Mari-Leen Kiipli, Tea Záchová, and Andrew Gryf Paterson, occasionally joined by Diana Lelonek and Linda Kaljundi) performed a collective cleansing ritual to prepare the moldy space of the former heating station for a new existence as a culture center, a spot for intangible warmth. Loaded with thoughts, we put our hands together and walked around the hall in silence. It was a bright day and the sweet earthy scent of solidago—a plant common in the Latvian landscape—filled the space. Solidago canadensis is an invasive species and, typically, is one of the first plants to colonize an area after a disturbance (like fire). It also tolerates both dry and waterlogged sites. It can be highly aggressive toward other plants and tends to form monocultures within its native range. It is, nevertheless, greatly favored by bees and wild animals.[11]

There are so many clashes yet to consider.

[1] Official Statistics Portal of Latvia, Population at the beginning of year, population change and key vital statistics 1920–2022.

[2] The unbuilt Riga Metro can be explored with the visualization available at “Riga Metro Atlas: A Virtual Tour Along the Never Built Subway,” Capital R (6 May 2020).

[3] According to the official statistics for 2022 on the distribution of Latvia’s population by nationality and citizenship.

[4] See Дисципліноване бачення / Disciplined Vision at ladanakonechna.com.

[5] Caitlin DeSilvey, “Postpreservation: Looking Past Loss,” in Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), p. 3.

[6] For more on the problem of “compromise” in relation to the war in Ukraine, see Bohdan Kukharskyy, Anastassia Fedyk, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Ilona Sologoub, “Open Letter to Noam Chomsky (and Other Like-Minded Intellectuals) on the Russia-Ukraine War,” e-flux (23 May 2022).

[7] For greater detail on Oleksiy Radinski’s take on the Nordstream project, see “Is Data the New Gas?,” e-flux 107 (March 2020).

[8] Jakub Gawkowski, “Seaberry Juice in Extractivist Ruins: The Cosmopolitical Art of Diana Lelonek,” ARTMargins (15 August 2019).

[9] Bruce Robbins, “The Sweatshop Sublime,” PMLA 117, no. 1 (January 2022): 88–97.

[10] Madina Tlostanova, Decoloniality of Being, Knowing, and Feeling (Centre of Contemporary Culture Tselinny, Kazakhstan, 2020).

[11] For more on how Solidago canadensis intermingles with Valmiera’s local environment, see the essay by Postsocialist Ecologies Summer School participant Andrew Gryf Paterson, “Solidago Strengthens the Solarpunks,” Internet Archive (2022).