Speaking succinctly about intricate subjects and addressing sensitive topics with subtlety is a true art. Yet, despite our awareness of this universal truth, we often find ourselves navigating the labyrinth of linguistic errors, obscure pathways, and kaleidoscopic expressions when attempting to convey our thoughts. Artists, designers, and architects, however, possess a unique ability to articulate themselves effectively by translating their thoughts and personal opinions into tangible forms and content.

Art enthusiasts are accustomed to encountering individual voices in artworks, expressing their perspectives on various subjects. However, within the expansive realm of colors, shapes, and lines, there exist exhibitions shaped by visionary thinkers—often orchestrated by a single voice or a panel of them. Biennials, triennials, quadrennials, and the like, exemplify this phenomenon. The Venice Architecture Biennale stands out as one of the most eagerly awaited exhibition dedicated to architecture, particularly in its interdisciplinary form.

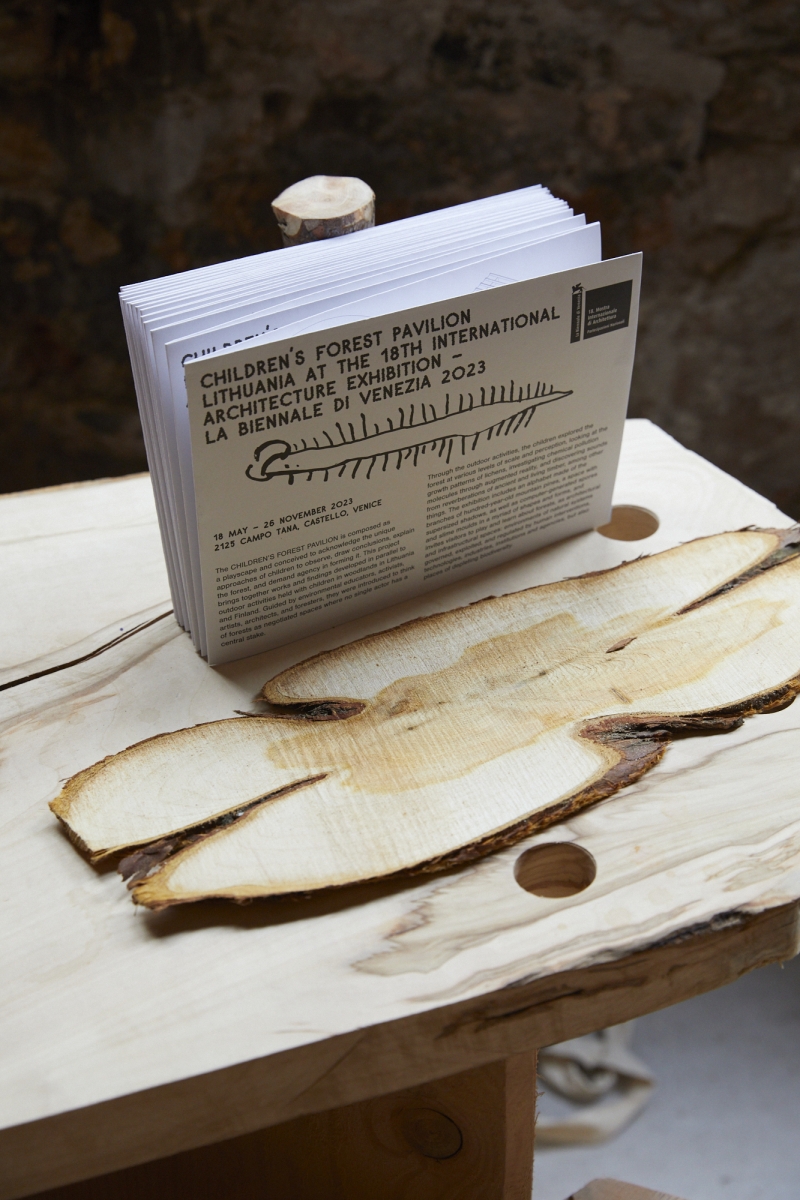

During this event, masters, connoisseurs, innovators, and pioneers converge to articulate, discuss, and captivate audiences—an atmosphere guided by the year’s appointed curator. This year, Lithuania entrusted the representation of its artistic prowess to the Children’s Forest Pavilion. Helmed by curators Jurga Daubaraitė, Egija Inzule, Jonas Žukauskas, and with Ines Weizman as commissioner, this project was a standout in the 18th architecture exhibition.

Sources indicate that this exhibition was the second most attended in the entire history of the biennale. With 64 national pavilions and additional programs, it drew a staggering 30101 visitors, with 38 percent comprised of students and young enthusiasts. So with these facts on hands in this interview we delve into the genesis of the Children’s Forest Pavilion project, the significance of participating in such a monumental event, the meticulous work plans and strategies employed by the curators, why children were placed at the core of the pavilion, and how one should contemplate the forest and its architecture.

Forest Layers Shadow Play by Mustarinda Association, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija Grajauskaitė: Greetings from Rotterdam and what a pleasure and an honour is to meet you all! Even though it is via distance, it’s still nice to have an opportunity to use internet as a tool of connection. Honestly, I’m particularly thrilled about this interview for several reasons, one being my involvement as an expert in the Lithuanian Council for Culture’s procedure to select Lithuania’s representative for the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Your project, the Children’s Forest Pavilion, was a standout for me, and I was elated when it was announced that you would be representing Lithuania. By the way, heard glowing reviews about the experience and am truly proud of the accomplishments and contributions made. So, I guess that sets the tone for our conversation, as I already gave out to be a fan.

Let’s delve into the details – the press release describes the Children’s Forest Pavilion as a playscape, designed to acknowledge children’s unique perspectives in observing, drawing conclusions, and explaining the forest while empowering them to influence its formation. I’ve read this description multiple times, and now curious to know how the concept for such a pavilion originated and who or what inspired its inception.

Timber Reverberations by Tuomas Toivonen, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Jonas Žukauskas: Neringa Forest Architecture project began three years ago as a reflection of forest as a constructed, infrastructure space. Considering the role of culture practices in communicating diversity of processes in the forest space to wider public, the project became one of the ongoing Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts programmes, yielding various outcomes. Each iteration of the project takes on a new form, whether it’s a building, a residency programme, a playscape, a public display, or a collaborative effort resulting in a publication. The design and the curatorial concept of the Lithuanian pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia 2023 emerged from our contemplation on how to respond to the biennale in general, what could be our take on being there? For us the idea of actually being able to read the complexity and layers of forest very much relates to children, to forest literacy, to knowledge, to play, non-linear approaches which actually relate to architecture as a medium to communicate intersectionality of forest. A response that once came through discussions we had was, Egija, you were saying: “oh, let’s make it actually for children” – thinking about the long-term processes in the forest space it became clear that this will be our approach in the process of finding a form for the pavilion; it felt inevitable to dedicate the pavilion to children.

Egija Inzule: Considering the context of the biennale and the challenges it poses, we were looking for an approach that would allow us to go further with the Neringa Forest Architecture project itself. We didn’t want to bring something prefabricated or rely purely on knowledge we had already attained throughout the past years while working on the Neringa Forest Architecture project in its manifold forms and formats. Instead, we aimed for a year-long process of working on this project, challenging ourselves and the community we collaborate with, and thus contributing to the Biennale that we mainly see as a platform of sharing diverse ideas and propositions regarding issues of our times.

Jurga Daubaraitė: In essence, we all once used to be children, and we wanted to establish a connection with the younger generation when contemplating the future of the forests. Our decisions and desires may be somewhat belated in terms of certain timelines, and by focusing on children, we aimed to address the long-term processes in the forest that extend hundreds of years into the future. There was a desire to include a new audience in this concept.

Aistė Marija: Just to clarify, the word ‘children’ in the pavilion is not metaphorical; it’s quite literal. I’m interested in understanding how you navigated the potential challenge of low attendance by children themselves. Building a project centered around children’s involvement carries its own set of considerations, especially considering the status and honour of the Venice Biennale of Architecture, which traditionally doesn’t attract many young visitors, it’s intriguing to explore the decision-making process, especially from your perspective as art professionals and parents. How did you overcome the internal concerns of whether the project would attract enough children? And how did you approach the promotion of such a project?

Jonas: We were conscious of reflecting on what an architecture exhibition might be, especially in terms of a space designed for children. The Children’s Forest Pavilion brought together a myriad of materials, forms and colours, casually not associated with playgrounds in Lithuania. Playing with the conventions of an exhibition was an attempt to have more openness. Here, those who are not yet reading the letters, were invited to read the space through tactility, through materiality, by touching surfaces and artefacts – through this intuitive tactility, inevitably comes the idea of play. Even before one thinks it is for children. The pavilion was an assembly to reveal the layers and complexity of forest through critical structure of play. The installation was accompanied by publications, exhibits and a film, each conveying a form of knowledge.

Mountain Pine Alphabet by Mantas Peteraitis, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija: I’m curious about the genesis of the decision to connect the project with kids… The question arises, have you already had any experience in projects involving kids? And do I understand correctly that the Neringa Forest Architecture project was like a point of resistance for this suggestion of incorporating children into the narrative?

Egija: Three years ago, when we initiated discussions about the Neringa Forest Architecture project, the first books ‘Forest and the Little One’ and ‘The Secret Book of Lichens’ published as part of it were explicitly for children. At that point in our collaboration, we were curious about our diverse backgrounds, including Jurga’s past research on playgrounds. Critical discussions about public space and its suitability for different generations, particularly in Neringa, where the project is situated, played a pivotal role. We all have witnessed how over the past decade in Lithuania and the Baltics, existing playgrounds have been dismantled and exchanged to identical pre-fabricated ones. This transformation, marked by safety-approved designs, raised questions about the materiality and the lessons imparted through play for the future decision-makers.

Aistė Marija: Adding a bit to what you mentioned, Egija, the last three or four biennials of architecture, for me, felt rather repetitive and conventional, and though everyone seemed to be addressing the main climate issues – rising water levels, burning forests, air pollution and so on – the approaches of it didn’t made impact or impression for me as a part of public, and audience just didn’t encounter anything like the Children’s Forest Pavilion. Regardless of the approach, the idea itself is refreshing and reading about it was genuinely interesting. It encourages reflection and challenges one to rethink the current reality. The project, even on paper, felt palpable and transformative. The connection between the woodlands of Lithuania and Finland intrigued me, though. Why Finland?

Jurga: The inspiration largely stems from Jonas’ and my experience at residency at Mustarinda two years ago, that is situated near Paljananvaara old-growth forest in Kainu region, northern Finland. There we encountered numerous educational, artistic, and scientific research projects in progress. Conducting our own research in Finnish forestry, we realised how much Lithuania looks up to Finland as an example in managing forests as a valuable resource. The pavilion wasn’t strictly a national representation; it transcended fences and borders. Looking north made sense, especially considering the impact of climate heating, resulting in new forests and tree species appearing in Lithuania. It seemed fitting to expand our focus to the north.

One significant aspect is the forestry methods; another meaningful area of research is the societal discussion in Finland, specifically how society is actively engaged in forest processes and shaping the future of their forests. We anticipate a similar transition in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Here forest processes are inherently slow, and traces of historical events, including Soviet times, are still visible. Society is reacting; forestry laws are being written, discussions about trees in cities and clear-cuts in the Baltics are emerging. However, the involvement and division in society are not as pronounced as in Finland. We find it crucial to learn from these processes and create a platform for discussions, involving children, scientists, and various experts working on forest-related topics in these countries.

Jonas: Within the context of the pavilion and Neringa Forest Architecture project, we aim to bring diverse perspectives on the forest, different ways of interpreting, working with, and looking at it. It’s essential to acknowledge that everyone in the forest has varied viewpoints. There are extractivists who see forest as a resource and there are those who see it as a place for biodiversity. We are approaching the forest from the position that it is not a natural space – it’s a construct in constant negotiation.

Jurga: Forest literacy.

Forest Layers Shadow Play by Mustarinda Association, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Forest Layers Shadow Play by Mustarinda Association, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Egija: Adding to the question of the Finland-Lithuania context, another aspect is the question of cultural and institutional collaborations. At the Children’s Forest Pavilion we were looking at two different kinds of forests. In Finland it is an old growth forest on Paljakanvaara hill. Mustarinda, a cultural institution located next to it has developed practices of working with their immediate context and resources. On the Lithuanian side, there is another cultural institution, The Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts situated in a human planted forest, that one could say, is on its way to potentially becoming an old growth forest. Neringa forest planting started around 200 years ago as part of an infrastructural effort, the afforestation of the sand dunes. Within these different forest typologies and the practices of these cultural institutions, the project developed based on our experiences working there and / or being exposed to their approaches.

Aistė Marija: The project involved, as you write in the press text, “guiding various age groups of children through the forest with environmental agents, educators, activists, artists, architects, and foresters, emphasizing the idea that forests are negotiated spaces with no single actor holding a central stake”. Why was this concept crucial to your team, and what interesting data or insights did the project yield? Furthermore, for readers less familiar with the material, could you elaborate on the choice to collaborate with such a diverse group of individuals and explain your goals, particularly in the context of the project’s continuation beyond the biennial?

Jonas: As curators of the project we believe that the forests and environment in general are in crisis. Our proposition is that architecture could work to interconnect all that is at work in a new way. The pavilion is not an attempt to write a scientific paper or propose a policy, but it is concerned with making an image, an active image, not representation, but a detailed blueprint of how to reconnect knowledge, sensibilities, how to interweave, rewire things.

Jurga: An example of this approach is evident in the materials used for the platforms, sourced from Neringas’ forests. Timber, which would otherwise become biofuel chips, is transformed into planks. The sticks, crafted by Mantas Peteraitis, are the old mountain pines, providing a tangible connection to the forest’s temporal processes. This approachable interaction allows for a deeper understanding of the forest’s chronological developments.

Egija: The diverse group of environmental educators, activists, artists, architects, and foresters each have a particular take on the urgencies in the forest space. While working on the Children’s Forest Pavilion we looked closer into various approaches related to education processes at stake in forest in Lithuania. Among them the ‘Young Forest Friends’, an initiative by Lithuanian State Forestry and its active department of Kretinga Forestry where activities with children are led by Tree planting specialist Gražina Banienė, for instance. There is a difference if educational activities are conducted from the perspective of those agencies interested in forest as a space of extraction, or those focusing on forest as a space of biodiversity as in case of the educational activities developed by Mustarinda Association in Finland, a transdisciplinary approach that involves environmental educators such as Riitta (Nyyskä) Nykänen as well as artists and art educators such as Tiina Arjukka Hirvonen, Michaela Casková, Robin Everett just to name a few among the association’s members who mainly participated in the Children’s Forest Pavilion and developed a workbook that can be used in formal and informal education settings providing suggestions for activities to be conducted with children in forests contextualised with insights in forest processes. Thinking of educational tools, the installation includes a timeline developed by the researcher Gabrielė Grigorjevaitė comparing industrial and old-growth forest timelines, as well as a study and special focus on the Ancient Woods Foundation in Lithuania and their work as NGO to select forest land plots it buys for conservation purposes. As an educational tool the pavilion was activated during spring and autumn when it was used by school groups from the neighbourhood schools as well as educators involved in informal education. Especially in spring Riitta (Nyyskä) Nykänen was there to give guided workshops to the school groups, but also to teachers who later could come and visit the pavilion on their own.

Jonas: Forest industry, climate heating threatening biodiversity is an extensive topic, we are interested in how to ‘make peace’, how to bring those things together. How to see biodiversity not as something closed in conservation areas as it is often the case in Lithuania where you cannot enter strict nature reserves to know what is happening there. The project is trying to propose ways where polarised conditions meet together, where they overlay. In the forest things change, species adapt to new conditions but new conditions brought in by timber industry and climate heating are so fast that diversity of species has no chance to adapt – highlighting new connections and sensibilities might be essential for moving forward in policy, future planning, and long-term considerations.

Moss Hats and Shawls by OSRZ-4: Banan Vedro, Circulation of Infernation, Doch, and Heorhii Hohatadze, Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija: So how much has the project evolved from its original concept, as outlined in the script submitted for the Lithuanian Council for Culture’s contest? Because in the initial submission, I read the primary idea along with additives, visualisations, and a list of potential participants. After learning about the project’s success, I haven’t seen the physical material. My curiosity lies in understanding, once the project wins, does the Ministry or Council require it to adhere strictly to the submitted proposal? Did the project undergo significant changes from the original written concept? And to what extent did the environment and the people encountered during the pavilion’s creation influence or alter the initial vision?

Egija: I believe ‘change’ might not be the suitable verb here because what we proposed was a container—a porous blueprint, indicating that the project is to be formed through the year-long-process in front of us and the collaborative work. The significance and relevance of collaboration cannot be stressed enough, and we are immensely grateful to all those who joined us, and contributed to developing the project together. Throughout this process, the initially outlined elements acquired specific shapes. In our visualisations, we showcased materials and objects produced during the three years of the Neringa Forest Architecture residencies and other iterations that were joined by the new productions at stake, during the Children’s Forest Pavilion working phase. Some preconceived ideas found their final forms there, for example.

Jurga: Certainly, the project’s contributors were scattered across different geographies, leading to many distanced conversations. We meticulously planned who would arrive in Nida when, what each contributor would bring, and the subsequent collaborative process unfolded during their time in Nida. It was a flexible process without a specific script, except for outlining available materials and the space. Jonas, along with Jurgis Paškevičius, Antanas Gerlikas, and Anton Shramkov, worked during the winter to design and build the platforms and shed that would accommodate the various contributions. In parallel, we worked on two books, four posters, and information displays.

Aistė Marija: Am I correct in understanding that there is a lingering hope that the Children’s Forest Pavilion won’t end up as a disposable, one-time project? Could you share your aspirations for the project after it’s disassembled and returned, perhaps, to an unknown location.

Jurga: We are in the midst of negotiations for the pavilion’s new location. Initially, we did a pilot version of the pavilion in Nida, showcasing it to the local community, foresters, the municipality, and the National Park—essentially, everyone involved in the Neringa Forest Architecture project over the past years, either as tour guides or supporting us finding ways how to access and acquire the local timber material we have been working with, that is at the centre of the project. Over the past years we have engaged in discussions with the National Park and foresters to redirect timber that would otherwise become biofuel into the pavilion’s construction. When presented in Nida, we received very positive feedback and support, attracting a significant number of people, especially families with children. Our desire is for the pavilion, possibly in a slightly different configuration, to return to the Neringa forest, functioning as an educational public space.

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija: Returning back to its origins—what a ruminative and beauteous concept! Shall we cover involvement of Ines Weizman? Curious to hear how did she become part of this project and what were her ideas, and what responsibilities did she assume in the project?

Jurga: To provide some context, Jonas and I have known Ines for a long time, dating back to our days in London, where she was initially a friend, then a teacher, and eventually became an inspiring collaborator for numerous projects. This connection grew, including our assistance in projects like Dissidence Through Architecture, where we invited her to Vilnius to curate together one of the Architecture Fund’s talk series back in 2013. Ines has been influential not just as an architect but as someone seamlessly integrating pedagogy, stories, histories, and architecture—making her an inspiring choice.

Jonas: We saw Ines’ role as someone who could sharpen the project, in the formal ‘commissioner’s’ sense, she played the role of demanding clarity, accountability, answers, and focused propositions. In many ways, she acted as an ‘oracle’ of architecture, a figure we felt was essential in this context.

Jurga: Having worked with various ‘oracles’ of the forest, we recognized the need for an architectural perspective.

Egija: Ines is familiar with the project, the Neringa region and Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts as institution, having been part of the Nida Doctoral School context for the past two years and having visited Nida multiple times.

Aistė Marija: Excellent. Now, let’s delve into the responsibilities among the three of you. While three might seem like a crowd, how did you divide and handle the tasks? Were you all hands-on or did you split the burden of responsibilities?

Egija: Reflecting on our collaborative and collective work is an ongoing process. We consider ourselves a young collective, three and a half years is not a lifetime. The complexity of collaborative work involves navigating various competences that each of us brings. We’ve organically developed an approach of acknowledging what we each are good at, listening and sensing the direction of our collective work.

Jurga: Our approach involves calendars and task lists, assigning roles based on capabilities. It’s a fruitful collaboration that’s back-to-back.

Jonas: The assembly leads to a unique and encouraging result. Working on separate registers and discovering new aspects, especially in building communities, whether contributors, residents, or those handling technical, bureaucratic, theoretical, or writing tasks, working together is a fascinating and open-ended process.

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija: The dynamics seem to be the key, creating synergy that allows things to unfold naturally and organically. The calendar approach adds productivity, tackling hurdles effectively. Thank you for covering the pavilion’s idea in the ten questions. Now, let’s delve into the architectural aspect and your approach to it.

Jonas: This year’s biennale – titled The Laboratory of the Future – incorporated an educational aspect. In the overall concept of the curated exhibition, the curator Lesley Lokko made a clear move, shifting the focus from highlighting Eurocentric perspectives on architectural practices to presenting architectural practices from Africa. By reflecting such an inclusive approach our project is an attempt to question the usual role of architecture and the terms it uses, for example we intentionally refrained from using the term ‘sustainability’ while thinking about relationships in the forest space that go beyond human interests. The term ‘sustainability’ appeared only in Forest Time, the forest processes timeline composed by Gabrielė Grigorjevaitė, where she mentions sustainability as an extractivist practice that sees forest as a source of timber while excluding biodiversity. We tried to be conscious towards using these terms while proposing to question them. We felt aligned with the concept of the Biennale as all of these notions in this context are critically assessed, reinvented, rethought, unlearned and relearned – it is an assembly where propositions meet; being here is being in conversation.

Egija: When seeking a space, we envisioned immersing the project in an existing public structure in Venice. Initially, I personally wished to collaborate with already existing infrastructure in Venice responsible for education, like the ludoteca: a play space for children and youth in almost every city in Italy. However, upon realizing that most considered spaces in Venice were affiliated with religious organizations, meaning following a historically complex agenda with a heavy backpack, we shifted the focus. Having visited Seven Common Ways of Disappearing by Andrius Arutiunian, the Armenian Pavilion at the Art Biennale in 2022, that was installed in a space used for Biennale for the first time, originally a domestic space, historically inhabited by Arsenale’s firefighters’ families, was turned ‘raw’, with removed doors and windows that felt like an in-between space where lines between inside and outside appeared blurred. This became a meaningful starting point for developing the installation, contemplating what an accessible space meant for the exhibition’s duration. Obviously we can delve into the topic of Venice, its relation to spaces used for Biennale pavilions and urban politics of Venice Biennale in another interview. Partially these questions were addressed during the public talk that we organised together with the teams from the Latvian, Estonian and Austrian pavilions in September.

Jonas: The choice of location in Venice was crucial. We aimed for a crossroad, contributing to both local life and the biennale. The Children’s Forest Pavilion was an exhibition but it also served as a public space, accessible without payment. The pavilion’s location, near the Arsenale and a bustling street, inspired us. We sought to create a specific installation that complements and enhances the existing flow of people mainly from the neighbourhood. The pavilion was located on the ground floor of a Venetian house, with spaces connecting the entrance from the street with the exit to the canal. The installation floated through the window, into the courtyard, creating an ambiguous semi-interior, semi-exterior area. Platforms formed a seating space in the courtyard under the specially constructed roof for hosting public events like discussions and readings as well as educational activities with children. All through the space were scattered QR codes linking visitors to Eco-Monsters inhabiting the augmented reality created by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas. The last room towards the canal was dedicated to a slower reflection contemplation and taking a breath.

Jurga: The final room, with its film about Neringa and Paljakaanvaara forests workshops we have created together with the Mustarinda Association (Tiina Arjukka Hirvonen, Michaela Casková, Robin Everett, Riitta (Nyyskä) Nykänen), invites visitors to experience slowed time. The forty-minute film beautifully edited by Igne Narbutaitė was shown on two screens, allowing viewers to sit, relax, and engage in the stories and activities guided and narrated by the environmental educator Riitta (Nyyskä) Nykänen in the diversity of forest conditions. The room included hidden spaces for children to play quietly, emphasising the immersive nature of the pavilion. Additionally, there was a shadow play area, concluding the structure of the pavilion a somewhat dark space with thin timber cladding, resembling a cocoon where one of the usual activities in the workshops conducted by the Mustarinda Association was installed. The timber, sliced from logs into thin sheets while still wet, was assembled on a grid structure to form this immersive dark space. It dried on the wooden structure, creating an inside-of-a-tree atmosphere. The overhead projectors magnified the silhouette drawings and tiny objects found in the forest during the outdoor activities: leaves, moss, branches, lichens, pine needles…

Aistė Marija: It’s winsome to witness how all of you speak about everything from the significant aspects to the smallest details with such love and affection. Very beautiful.

Jurga: We enjoyed being in that space, and we’ve heard from students looking after the pavilion that it was a genuinely pleasant place. The strong smell of timber and the dried wood, a bit shadowy but not dark, created a unique atmosphere. Tuomas Toivonen’s sound recordings from different timber reverberations, including the occasional woodpecker, added to the forest ambiance. It was a spatial presence.

Aistė Marija: Let’s move on to the next question. As we’ve discussed, you integrated film installations, work tables, and play structures, creating architectural elements emerging from various ideas. Considering your earlier coordination in 2020 and the research methods used, how did you conceive the pavilion’s body as it is now? Did the previously gathered data have a significant influence?

Egija: At the core of the pavilion was the work conducted over the past three years of the Neringa Forest Architecture project. This included many conversations that had materialised in one way or the other but that we consider ongoing, since we are all working on, and joined by such a vast, complex and multifold topic. For example Gabrielė Grigorjevaitė was one of the first residents who participated in the Neringa Forest Architecture residency programme three years ago in Nida. In 2021, when Jurga and Jonas were invited to edit the first issue of ‘As a Journal’ magazine by the Lithuanian Culture Institute their ‘Forest As a Journal’ joined a number of the first materialisations of the residency programme’s research results. The conversations that started in Nida were already ongoing when we started working on the pavilion.

Jurga: Gabrielė’s cards, with texts and diagrams explaining forest processes were laid out as a timeline through the pavilion’s structure meandering through the rooms and the courtyard. The extent of the timeline informed the structure of platforms accommodating Slime Mold Spores – 3D prints of computer generated forms by Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė and the branches, joints and knots of the Mountain Pine Alphabet by Mantas Peteraitis. This piece was central in all the activities by children as it allowed a free play of composing structures on the platforms.

Jonas: It’s about translating ideas into space by inviting to enter a layering, cartography, an assembly of knowledge, which, in a way, might reflect how libraries, classrooms, or various museum displays experiment with exposing knowledge. It’s a version of how one can navigate the diverse topics of the vast and complex forest.

Egija: Acknowledging the transdisciplinary nature of this project, we enter the forest space through the work of artists, through the work of researchers and other practitioners. Important maybe to highlight is that the installation and all the elements, are considered as translations of forest processes. This takes place when for example the size, or scale (which is a problematic term) in the installation were shifted and altered from the so-called “natural”. We always emphasize that, except for the film showing what can be referred to as the “usual” image of the forest space, everything else in the pavilion formed a deconstructed, constructed again, and a composed image-as-a-collage of forest. Like Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė’s magnified 4D reconstructions of slime mould spores that in the actual forest space or other places where they pop up in natural environments are miniscule, in the Pavilion they were integrated in this tactile, oversized dimension. Or Laura Garbštienė’s depiction of forest colours through the process of grazing sheep in the forest and wool dying with forest plants as an image of an imprint of the forest through these natural colors and processes.

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Aistė Marija: One of the last questions… You have an impressive number of participants in this project. The question that arises is, what is their role in this project, and as curators, wasn’t it challenging or perhaps even very complicated, to outline the program and envision who would work with you? How did you manage the diverse of all professionals that came together with the project?

Jurga: I remember when we started, we wondered if we could create a simple pavilion, something small and working as a tool, you know? Surprisingly, that’s how we managed the entire process.

Aistė Marija: Well, it seems like you handled it better than you initially thought!

Jurga: It’s still simple.

Jonas: I wouldn’t say the contributors have ‘a role’ in the project – they have created this project. All contributors, with their diverse work on different registers and shapes created this image of complexity – they were interrelated, contributing to each other. The layering of the installation is how specifically they come together. The film relates to the sound, the sound relates to objects, the installation relates to timelines, and, in a way, the interweaving is a weaving of conversations, work, and relations.

Egija: To add, everyone in this process has been very, very patient with the three of us. When one process started to roll, it was us taking time reflecting and learning. The script was established together, step by step. There’s not only patience but also the ability to listen through our translations, hearing reflections, and input. We were lucky and grateful to everyone ready to enter this uncertain and exhausting process.

Aistė Marija: You made it, so congratulations. The team looks extremely good. Each one is a professional in their field. The question is, can each of you sum up what this pavilion, this project is about and who it is oriented towards, not as a team but as individuals?

Jonas: I don’t want to simplify.

Aistė Marija: Simple is good, simple is the best. Simplification is not always negative.

Jonas: Complexity is not complication. The idea is that we cannot think about the complexity of the forest environment through simplification. It is many-dimensional space, an image of a forest is where many projections come together.

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Egija: The pavilion as an educational tool was thought to give access to this complexity or provide an entry point into the general understanding of the environment that we are based in, that we are surrounded by. We wish that the pavilion was used by many, by those involved in educational processes, those involved in making decisions for and about the environment. The idea is that when it goes back to Nida, all these agencies and the general public will find ways to use this material. That’s a challenge.

Jonas: Also, we should not forget that the installation was designed for humans to read forest processes.

Jurga: Not only. When it goes back to the forest, it goes back to all other forest inhabitants because it’s untreated wood. They could take it back. The project is an invitation to spend time in the forest, in silence and the processing of opinions, needs, and demands. We can respond to that with respect.

Children’s Forest Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia 2023, photo: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

More about the Children’s Forest Pavilion you can find inn: https://neringaforestarchitecture.lt/

Curators: Jurga Daubaraitė, Egija Inzule, Jonas Žukauskas

Commissioner: Ines Weizman

Architecture: Jonas Žukauskas in collaboration with Antanas Gerlikas, Jurgis Paškevičius, Anton Shramkov

Graphic design: Monika Janulevičiūtė

Poster illustration: Izadora Daubaraitė Žukauskaitė

Moss hats and shawls: Banan Vedro, Circulation of Infernation, Doch, Heorhii Hohatadze

Video production: Eitvydas Doškus, Elis Hannikainen

Video editing: Ignė Narbutaitė

Lighting: Martynas Kazimierėnas

Photo documentation: Rasa Juškevičiūtė

Coordination: Dovilė Lapinskaitė

Coordination in Venice: Marco Scurati

Communication: Stefanija Jokštytė, Anna Luise Schubert, Alexandra Bondarev

Translation Alexandra Bondarev

Proofreading Gemma Lloyd

Project assistant: Vilius Vaitiekūnas

Pavilion attendants: Rugilė Akambakaitė, Magdalena Beliavska, Augusta Fišerytė, Aistė Gaidilionytė, Rimantas Giedra, Gustė Kripaitė, Marta Dorotėja Lekavičiūtė, Gabija Naikauskaitė, Viktorija Narbutaitė, Kamilė Vasiliauskaitė, Gabrielė Vrublevska

Accounting: Rasa Bliakevič

Legal consulting: Neringa Savickė, Kotryna Volodkaitė

Contributors: Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė, Ancient Woods Foundation, Gabrielė Grigorjevaitė, Laura Garbštienė, Mustarinda Association (Tiina Arjukka Hirvonen, Michaela Casková, Robin Everett, Riitta (Nyyskä) Nykänen), Mantas Peteraitis, School of Creativity (Kristupas Sabolius), New Academy (Ikko Alaska, Nene Tsuboi, Tuomas Toivonen), Urbonas Studio (Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas), Kornelija Žalpytė

Organised by: Neringa Forest Architecture

Implemented by: Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts

Partner: Centre for Documentary Architecture

Supported by: Neringa Municipality, Nordic Culture Point, Lithuanian Council for Culture, Baltic Culture Fund

Thanks to: Artnews.lt, Gražina Banienė, Adriano Berengo, Yulia Derenko, Gaetano di Gregorio, Aurora Fonda, Laura Gabrielaitytė-Kazulėnienė, Pranas Gudaitis, Monika Kalinauskaitė, Dr. Mindaugas Lapelė, Laguna nel Bicchiere – Le Vigne Ritrovate, Marija Olšauskaitė, Rimantė Paulauskaitė-Digaitienė and Dr. Ainis Pivoras from the Ancient Woods Foundation, Viktorija Rybakova, Mindaugas Survila, Nida Forestry, Kretinga Forestry, the Curonian Spit National Park

Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts: Milena Černiakaitė, Vasilisa Filatova, Alberta Globienė, Giedrius Globys, Egija Inzule, Asta Jackutė, Dalia Jokūbauskaitė, Lina Košeleva, Aldona Lankauskienė, Elena Orlovienė, Daura Polonskytė, Anton Shramkov, Ieva Skauronė, Yana Ustymenko, Katerina Vaseko, Tetjana Volosiuk

All the children, educators, and schools who participated in workshops in Lithuania and Finland: Puolankajärvi Comprehensive School (Puolanka, FI), Hyrynsalmi Comprehensive School (Hyrynsalmi, FI), Neringa Gymnasium (Nida, LT), Young Forest Friends (Kretinga, LT), Baltupiai Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Gerosios Vilties Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Emilijos Pliaterytės Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Pavilnys Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Sietuva Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Simonas Konarskis Gymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Simonas Stanevičius Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Vasily Kachalov Gymnasium (Vilnius, LT), Vilnius Sofya Kovalevskaya Progymnasium (Vilnius, LT)