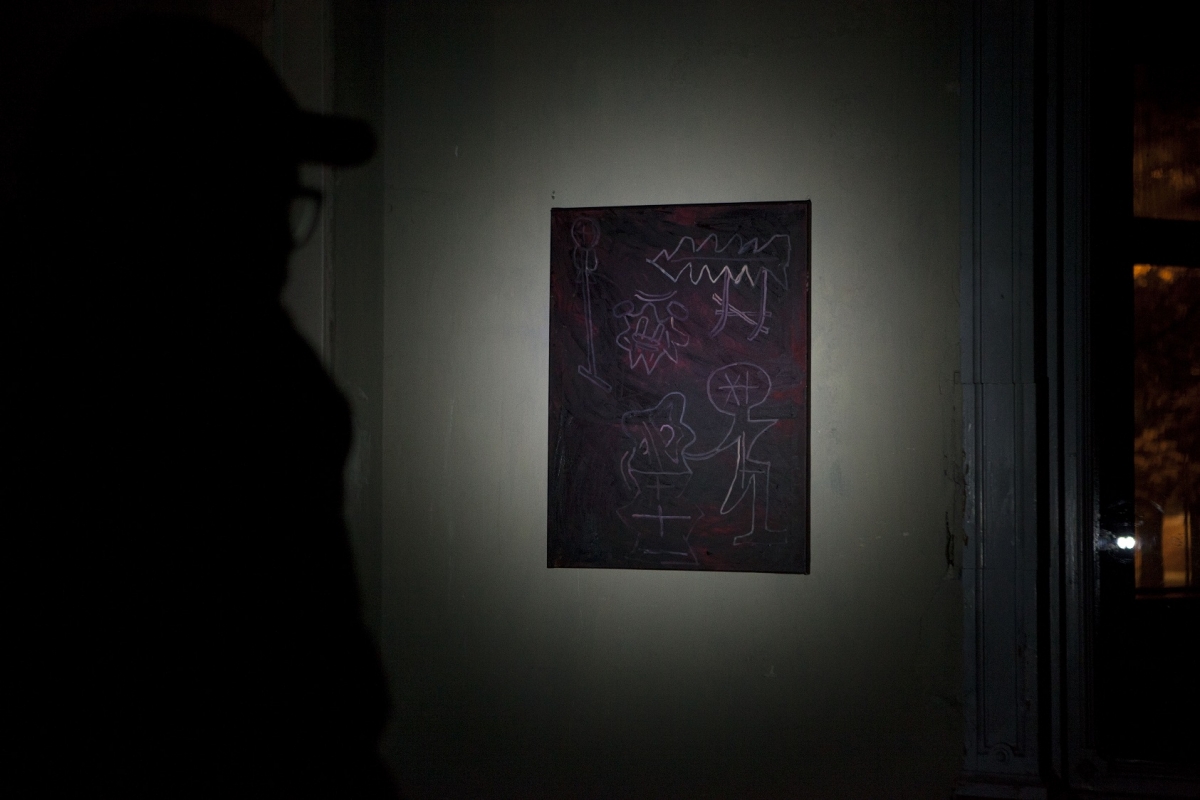

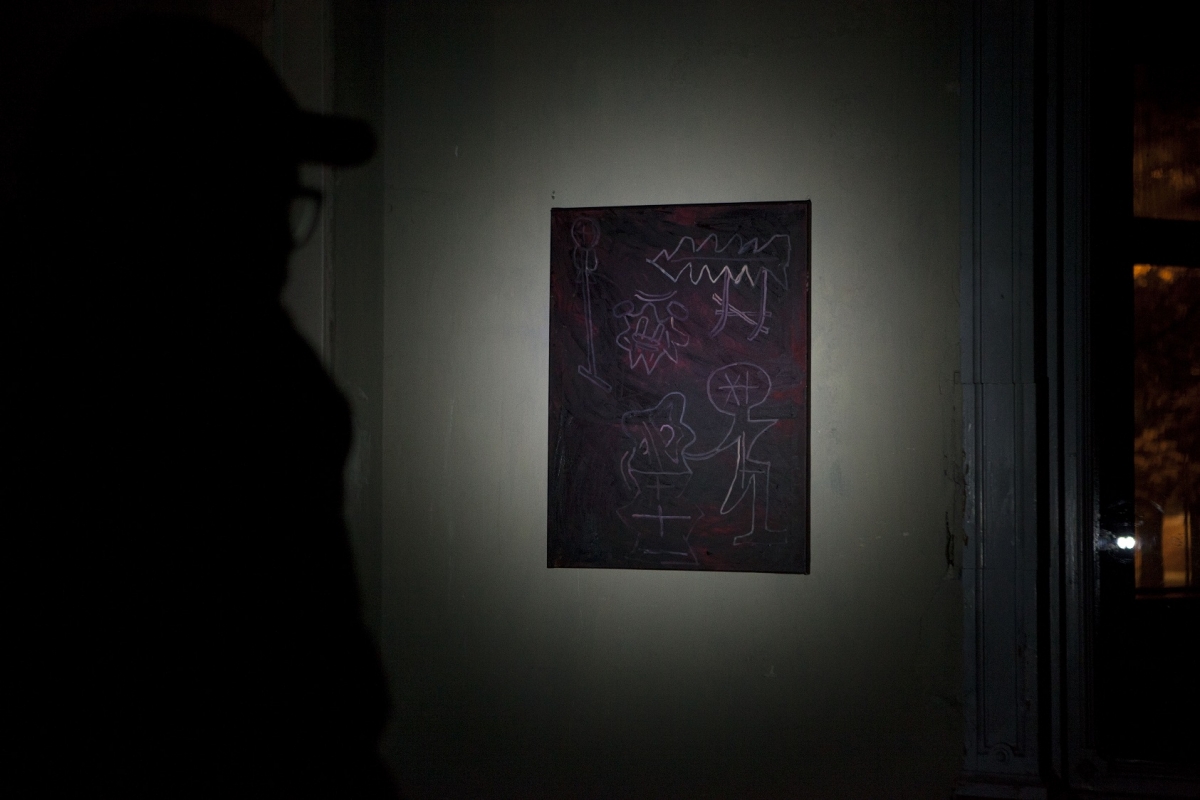

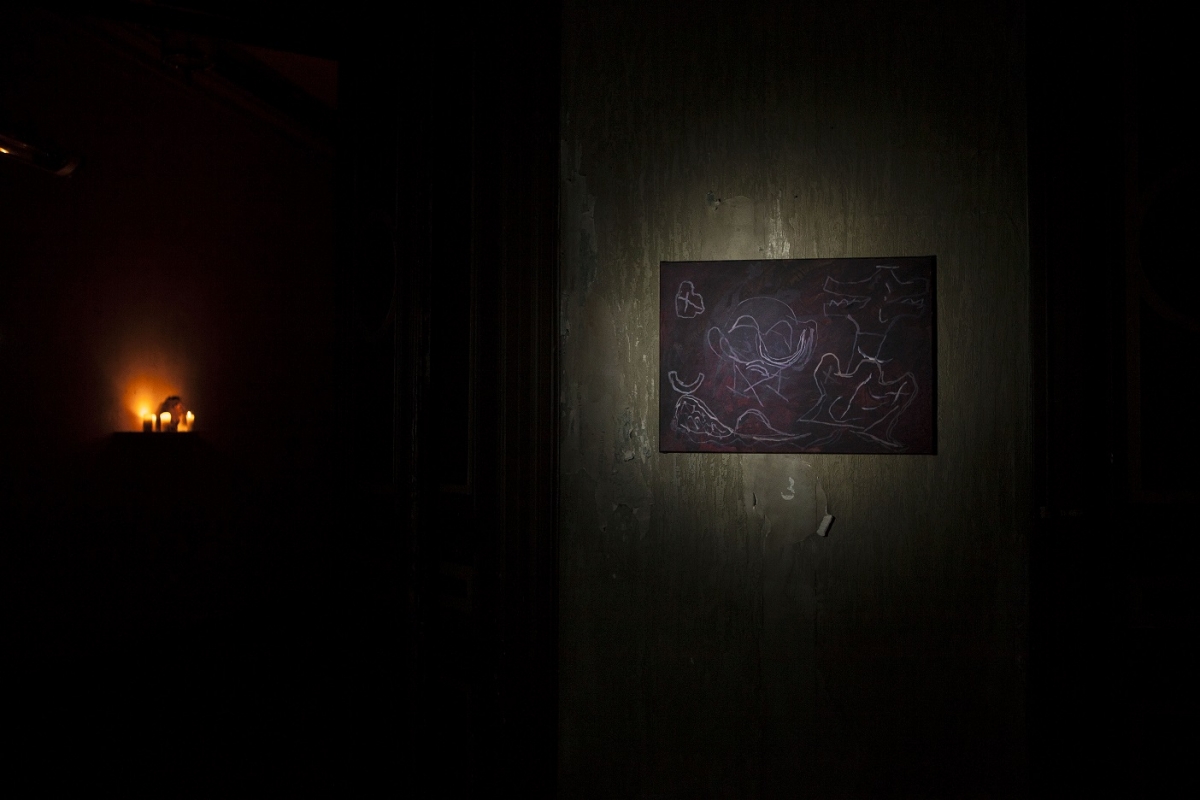

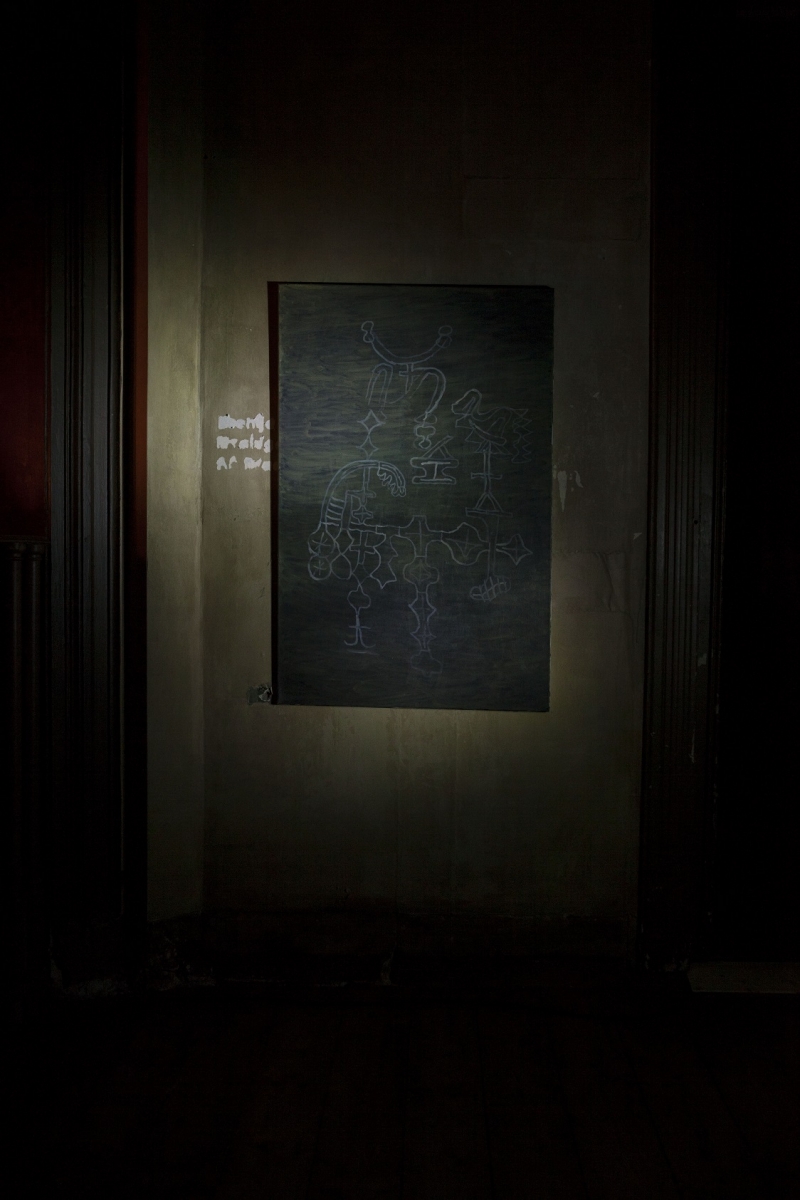

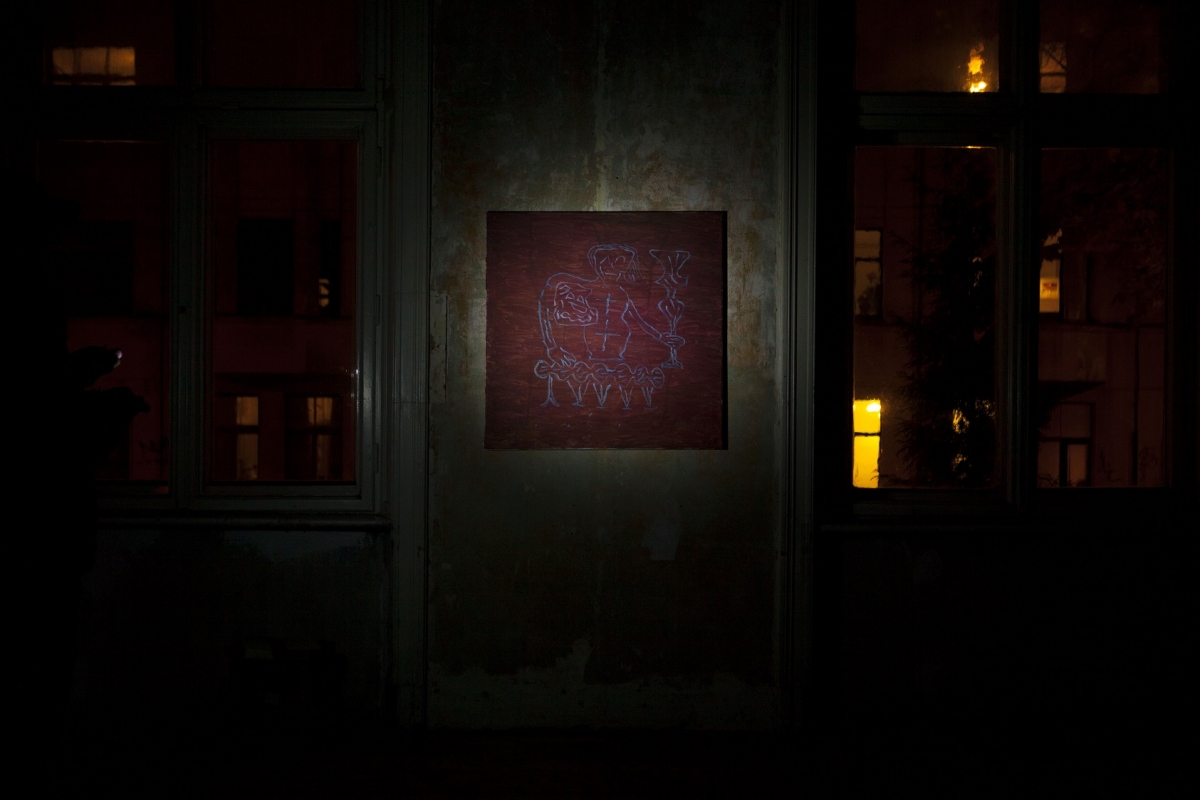

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

A review of the exhibition Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, 14.10-29.10.2016, C.C. von Stritzky villa

During the time when my Internet disappears, I usually read. Luckily, network problems are rare, and even then I can still use hotspot on my mobile. However, this fleeting sensation of force majeure liberation is fantastic. All of a sudden, there is this psychologically free space, where I can attend to matters somehow not considered a priority on a daily basis and thus postponed. The exhibition Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, curated by Kaspars Groševs, deals with similar sensations. All 12 paintings in the exhibition were created in contemporary isolation, in the 427 Gallery, where there is no Internet connection, and thus it calls for creative and flexible re-focusing, while having to adjust to these circumstances. It’s also a retreat of sorts.

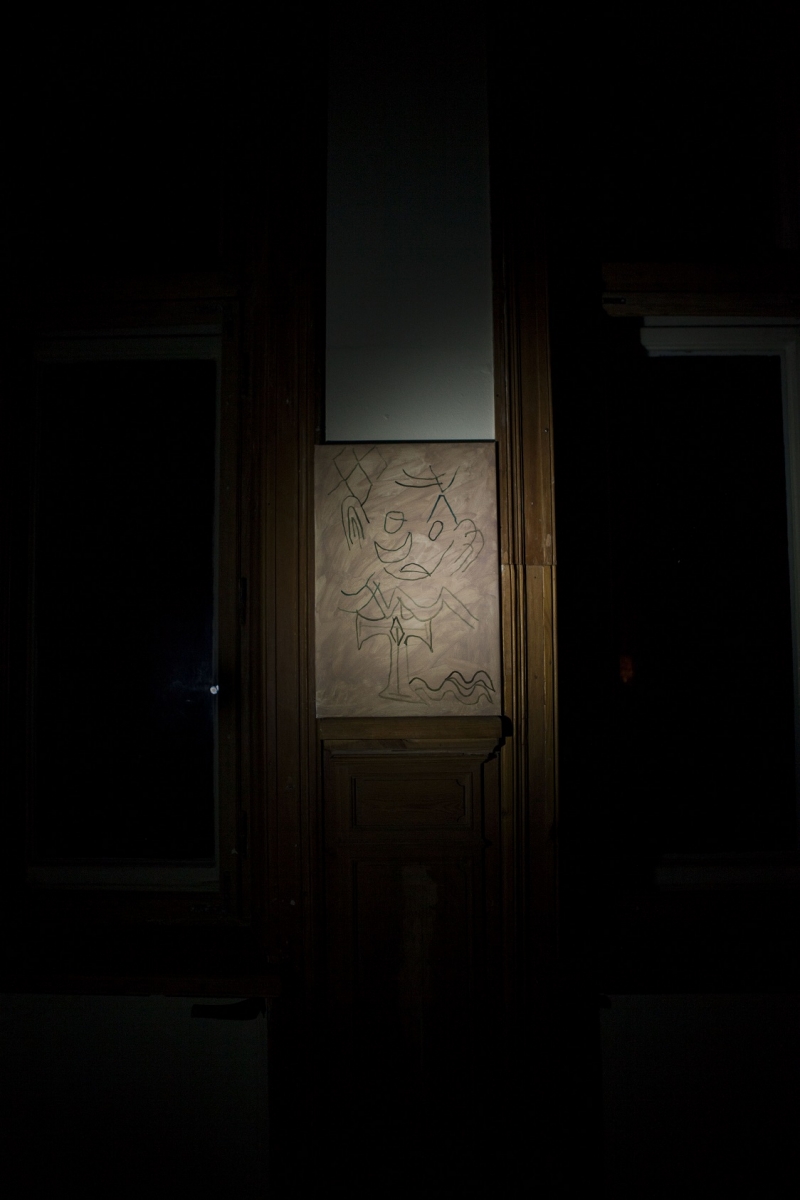

As an artist, Kaspars Groševs had his last solo exhibition in Latvia at the kim? contemporary art centre in the spring of 2013, after which most of his time was spent as a curator and organiser, and also taking part in group shows. After experimenting with several conceptual forms, in the exhibition Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint Kaspars has returned to the ‘roots’ of art, namely to painting in its traditional sense, oils on canvas. Although he never studied painting professionally, the desire to engage with this form of expression has not appeared out of thin air, so to speak. These paintings incorporate Kaspars’ drawings created over many years, which have also previously been present in his creative practice. The exhibition Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint took place in the abandoned C.C. von Stritzky villa. Although the building has lately been used almost too often as a trending and ‘cool’ place for events, it is hard to imagine a better location for this exhibition. From the outside, nothing suggests that there is anything going on inside: there are neither signs nor lights. Furthermore, the exhibition’s opening hours were rather modest, and equally as random as at the 427 Gallery, in this case from Wednesday to Saturday, from 6pm to 8pm, during hours of darkness. Darkness is an essential element for this exhibition, because the works are not lit in any way other than by the streetlights that shine in through the windows. Visitors had to bring torches with them, and locate each painting by themselves, as they journeyed from one room to another.

The rooms also contained items that had nothing to do with the exhibition, for example a scattering of tree branches, a broken flask, a disconnected PA, and a jumble of wires on the floor, all a potential tripping hazard (in the midst of all these props, it was delightful to spot the ironically placed Wi-Fi router in the exhibition rooms). Meanwhile, the relaxed invigilation encouraged ideas of certain acts of artistic vandalism: this would have been a great opportunity for spraying graffiti on the walls, or hanging one’s own painting somewhere, all the while remaining perfectly undetected.

The highly unusual environment is undoubtedly a vital component of this exhibition and its concept. At the same time, it is also a good marketing ploy: to utilise a peculiar location that also works in its own right. However, I must point out, on this occasion it was done in a very discerning and organic manner: the paintings fitted in naturally, almost as if they really had been left behind from some bygone age. The utilisation of this space for Groševs’ exhibition seemed more successful than, for instance, the previous exhibition, Survival Kit 8, where the dominant ‘trash’ of the interior of the C.C. von Stritzky villa was overly lit. On this occasion, however, the crucial romanticism was preserved. What is more, the side effects provided by this unusual exhibition experience, such as the sense of a sneaky trespassing, spooky occult atmosphere, created by candlelight, or even some sort of art horror room scenario, all of these were associations generated from the culture of ‘darkness’, and indeed pleasantly entertaining during the pre-Halloween season.

More important is the intertwining of Kaspars Groševs’ various aesthetic practices. His artistic thinking has always been infused with various cultural references, which nowadays, of course, is a widely applied and steadily approbated creative method in contemporary art. His work references the field of music a lot: after all, he is equally active in both visual art and sound art. This exhibition is no exception, and the story of the 1980s German pop duo Milli Vanilli (chords from their songs played in the anteroom) has been woven in as an erudition test: they did not actually sing on their own records. This fact precisely relates to Kaspars Groševs’ own role in the exhibition, as he sort of is and isn’t the author of it, and in this instance has presented himself as the curator only. It is a canny approach: why shouldn’t a musician, for instance, DJ his own songs? Just like the Holy Trinity in Christianity, where God’s hypostases perform various functions whilst still remaining one figure. In my opinion, this situation in art is perfectly possible without any contradictions.

The second important reference, however, concerns a Surrealism exhibition in Paris in 1938, where, as a result of a technical fault, visitors had to view the exhibition in darkness. Surrealism has a certain place in Groševs’ work, namely all those scrawls, patterns and decorations in his paintings contain within themselves letters, partly obscured figurative silhouettes and faces, all of which have been created in the technique of automatism. Just as we sometimes aimlessly doodle on a piece of paper while talking on the phone, Kaspars Groševs for the most part made these drawings during his lectures. Quoting in general is a characteristic of his art, including quoting himself. The process behind these drawings consists of repeatedly drawing the same composition over and over again, until it begins to feel like a completely new composition. Almost like distancing oneself from the self, and taking a look from the outside. As if the author’s body is physically performing the actions, while the mind is not involved at all.

The exhibited works are akin to a visual game, where the rules of basic composition have been deliberately broken, and unreal spatial compositions formed: each geometric creation reworks itself endlessly. In the dark, it was hard to detect the tonality of these paintings, and it seemed to alter depending on the angle and the distance of the light. Although the accompanying leaflet lists the title of each work, it is absolutely irrelevant which title corresponds to which painting. Randomly selected and various-sized frames further amplify the all-encompassing role of the chance factor. Added together, all these elements illustrate the author’s views: he likes to notice something new each time he looks at his work, and his work is open to interpretation. It is worth noting here, as a digression, that the notion of ‘free interpretation’ is probably one of the most widespread mistakes in professional contemporary art slang. Just as artistic reflection is regularly confused with a simple response or reference to certain situations or social political events, likewise, free interpretation is often taken to mean the possibility of reading the meaning or the visual elements of an artwork in a not incorrect way. Thus, free interpretation means that the viewer should be encouraged to perceive a work of art in a different way to the one originally envisaged. However, that’s not true in this case.

This stance would imply that, in order to create an aesthetic experience, neither an exhibition nor art as such is required, because everything around us can be freely interpreted. How far is this completely free interpretation meaningful to the viewer, and where does it risk turning into institutionally accredited diplomatic immunity for the artist, arrogant arbitrariness, or selfish irresponsibility towards the audience? This exhibition did not lack meanings. It became more interesting than it seemed at first. And the shambolic, even indifferent, way of presentation proffered freedom to its viewers, and possibly, due to this ‘underground’ format, the exhibition turned out to be very daring, and yet at the same time it remained accessible. It was an intimate opportunity to peek inside and sneak around the artist’s subconscious, simultaneously reflecting on oneself during this time of autumnal contemplation.

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe

Didn’t Have Wi-Fi So I Started to Paint, C.C. von Stritzky villa, Riga, 2016. Photo: Kristiāna Marija Sproģe