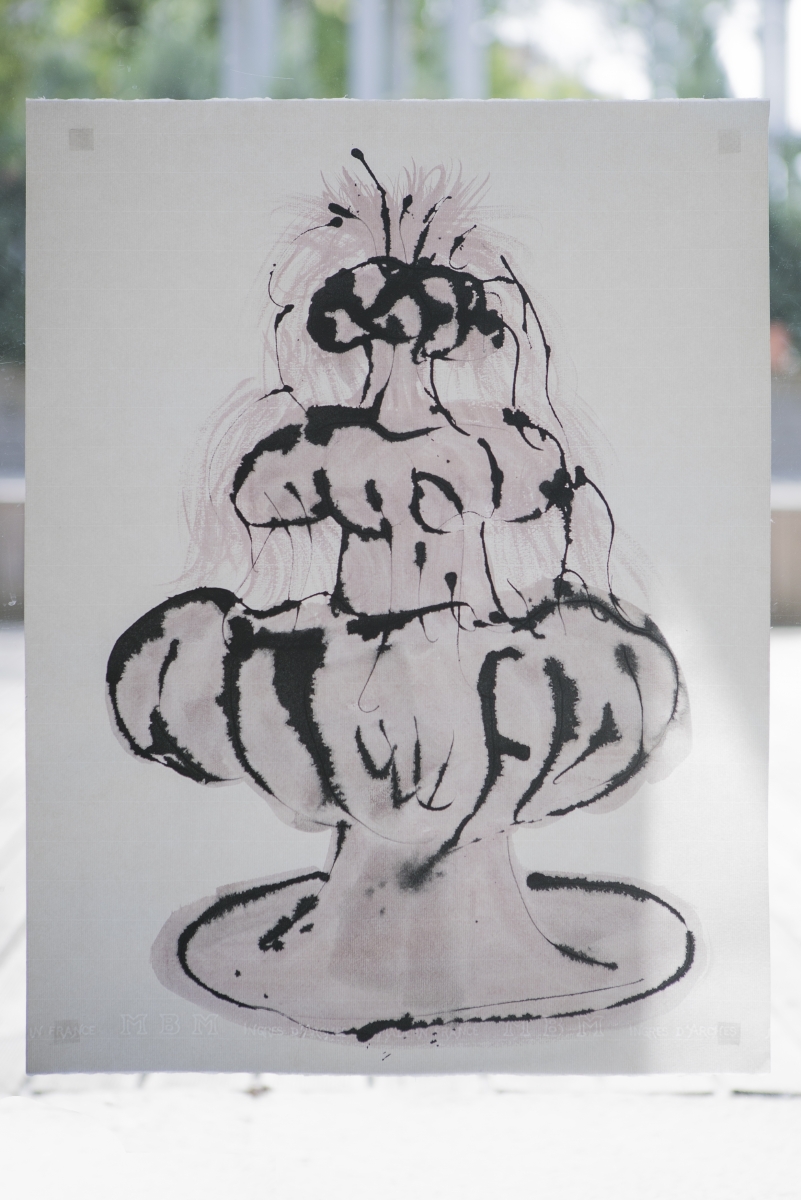

Justina Zubaitė: In 2019, you had a solo show ‘Sanatorium’ in the reading room of the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) in Vilnius. You presented a collection of watercolours, ink drawings and sculptural objects. One of the reasons that led me to invite you to do a show was the materiality of these works, and the wizardry of the paperwork that leaks organically into the space itself, but also gives it an unfamiliar and eerie feeling. How did drawing come to your practice?

Vytenis Burokas: There were ups and downs with drawing in my practice. As children, many of us make black and white doodles, or sometimes coloured circles, strokes, touches, lines or stains. These are usually extensions of our mobility. Sooner or later, we begin to develop our own creative vocabularies, and start to recognise the links between the circles we have drawn and those in the so-called ‘reality’. So drawing is one of the best ways to express our obscure and not yet articulated ideas and experiences. Then parents and art teachers come and help us with it, and our vocabulary of visual expression continues to diversify. At that moment, children’s desire to depict reality as they wish usually comes into collision with the rules of representation, and they are disappointed. Institutionally acceptable forms of drawing stop satisfying us, and since we already know how to communicate ideas in words, that is exactly what we go on doing: we practise verbalisation.

I was lucky enough to grow up in an environment which introduced me to cultural diversity. For this, firstly, I am grateful to my parents. It came by travelling, and by going to concerts, the theatre, exhibitions and artists’ studios. I remember autumns spent at the home of Bronius Kutavičius, when we would cross the Monkey Bridge over the River Merkys, picking mushrooms, listening to songs, and playing dangerously with the pieces of flint we found among the stones near the granary. I remember listening to Kutavičius’ 1978 oratorio The Last Pagan Rituals in the archaeological shed of the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, and going to his 2000 opera The Bear at the National Opera and Ballet Theatre in Vilnius. I look back to the musical improvisations by Tomas Kutavičius and Dalius Naujokaitis, and visits to the studios of the artists Linas Katinas, Petras Repšys, and many others. At the same time, I attended the Liepaitės choral singing school in Vilnius. All these musical and visual experiences affected me deeply, and I started to feel I was at the wrong school. Then I saw an invitation to apply to the National M.K. Čiurlionis School of Arts, and immediately signed up to take the entrance exam.

There I learned about new forms of institutionally acceptable visual expression. We would try out various techniques, and we were taught by great teachers, but this led to the false belief that we were already accomplished artists, soon to hold retrospective exhibitions and publish monographs. This elitist atmosphere, and the prevailing rhetoric of the school, was questioned now and then in the lectures and practices of unconventional artists and teachers, like Giedrius Plechavičius, Gediminas Akstinas, Džiugas Katinas, Antanas Jasenka, and others, who stood out with their optimism and their interest in contemporary art processes. We drew so much that after entering Vilnius Academy of Art, and out of inertia, there was a huge risk of never again thinking about ‘drawing itself, drawing without conventions’, and ways to practise it outside academic drawing.

With my stubborn character, and together with a few friends, I decided to stop drawing. As a result, we developed the conceptual quality of our works, and stronger voices of refusal, while we simultaneously noticed our dwindling ability to express ideas on paper or in other materials. The best decision I ever made was to study in the Sculpture Department, under the artists Mindaugas Navakas, Deimantas Narkevičius and Gintaras Makarevičius, and with lectures given by Agnė Narušytė, Laima Kreivytė, Lolita Jablonskienė and Arūnas Sverdiolas. Along with my conversations with many other professors and fellow students, it led me to understand my motivation and intentions, and enabled me to carry out bold creative experiments.

It took me almost a decade to see that I had experienced virtually all the changes of the late 20th century. At the specialised National M.K. Čiurlionis Art School, we studied classic modernist academic drawing, painting, sculpture, and other modes of expression. Then we applied to the Sculpture Department at Vilnius Academy of Art, and abandoned everything we had become used to (what distinguished us from previous generations was that we have never really, bodily experienced those transformations, or the transition from high modernism to postmodernist strategies, but learned to recognise and relive them through the narratives we listened to, and which were eventually turned into personal myths). We finally rediscovered the potential of working with materials, found objects, ephemeral, post-conceptual practices; while delving into multiple contexts and cultural references won us over. I started creating the series of works ‘Sanatorium’, about a fictional character who has also lived through these transformations, and after breaking out of restrictive social circles (I call it the ‘Order of the Spur’) began creating without waiting for permission any longer.

‘Sanatorium’, exhibition view, CAC Reading Room, 2019. Photography: Laurynas Skeisgiela

J.Z.: You open your story ‘Sanatorium’ with the following words: ‘I came to a sanatorium looking for peace of mind, for a break. And that was a transformative experience. I have experienced the revival of my creative powers, which, if only for a moment, helped me to silence my obsessive desire to make excuses for everything I do.’ Can you tell us a bit more about the characters in this story, about the mysterious ‘Order of the Spur’, and the particularly strange atmosphere of this fictional reality? Was it a conscious attempt to make the exhibition affect its visitors emotionally, and even bodily?

V.B.: The ‘Order of the Spur’ is a kind of secret society. I have always been fascinated by various conspiracy theories, and also by our inclination to huddle together in gentlemen’s clubs, political parties, movements, circles, etc. After reading ‘A Brief History of Portable Literature’ by Enrique Vila-Matas’, in which the author writes about a secret circle of artists, and what it does for its members, I decided to reflect on this topic in my work.

At some point, I stopped reading only professional literature (criticism, philosophy and art magazines), and looked back to works of fiction from various times. I asked myself ‘Why have I stopped creating works in the flesh?’ and after running through my reading list, I then understood that the books I was reading directed me towards the de-skilling of my artistic practice, and towards the concept of ephemeral art.

In critical theory, the discussions of the commercialisation and institutionalisation of art are still on the table, and authors continue to stress the importance of politically engaged practices, while also seeking new forms of art that might be resistant to markets. I am still strongly influenced by the legacy of the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, and the major disruptions in art history, as well as by the theory of aesthetics and criticism. However, I notice that artists nowadays usually learn how to be socially and ideologically engaged according to given patterns and practices, and this often leads to the loss of our sense of humour, and an extension of a pioneer-like puritanism. It can lead to a sort of paralysis of creation in material terms. The very moment you externalise something, it starts to interact with the outer world, and hence it becomes political. It does not necessarily need to be verbalised. The political message can be inscribed and embedded in the very logic of the production process. Sometimes the most silent object shouts at us with such violence, or whispers with such care and love, that we start to change ourselves and our relationship with the environment. The opposite can happen. If we only follow previous orders or modes of behaviour, or if we wait for someone’s permission to proceed, then I see a danger in art studies becoming the new academism, paralysing the initial urge to create. But I have to admit that it is crucial not to produce anything if it just happens to be a ‘learned’ urge, either because of peer pressure or contextual pressure, or because of other neo-liberal fumes tying us to the algorithms of ‘the right way to do it’ (just in order to be productive, and therefore successful). I sometimes recall Herman Melville’s ‘Bartleby the Scrivener’, and his calm but unmovable ‘I prefer not to.’

Ephemeral and ‘de-skilled’ art always seeks some sort of verbalisation or theoretical grounding. Thus, many artists (and I’m one of them!) found themselves hostages of this learnt way of doing philosophy. We were looking for references to shelter us and grant us permission to create new works. Then we started swarming around in groups or circles that might give or refuse this permission. I was tired of this Apollonian way of doing things, and started longing for a Dionysiac basis for creation, which would combine my passions for philosophy, art history and literature, and my material art practice. So I created an alter ego, and began telling stories.

To talk about these experiences, I use the setting of the ‘Order of the Spur’. This is a fictional secret society that unites all the nomads and self-critics, who keep an eye on each other and forbid anyone to pause or delve into slow motion or material practices in art, who practise constant movement, and create their works only at night while travelling. They are so close that even on the widest road they touch each other with the tips of their elbows.

This ‘club’ is also a reference to the novel Trans-Atlantyk (1953) by Witold Gombrowicz, one of my favourite authors. His style of writing (his characters, his language) and his way of living and thinking are very close to me, as is the fact that he did not fit into the communities and the cultural circles of both the old and the new Poland. My aim was to bridge these ‘clubs’, if only by symbolic links.

Imagine a horseman who uses his spurs to control a horse. After a while, the horse realises that the horseman is wearing riding boots with spurs, and so internalises this potentiality of pain, and starts self-taming itself. Members of the ‘Order of the Spur’ are horseless horsemen who use spurs to tame themselves. One of the members presses a spur into the leg of a deserter. Meanwhile, another one, seizing the opportunity, attempts to run away, but also gets spurred. What I see is an image of bodies joined together with spurs, turning into some sort of crown of pleasure and pain, which portrays both those running away and the efforts to keep everyone together. It is important that this image is not only masculine but also homoerotic, or at least non-heteronormative. By the way, DV8 physical theatre and their choreographer Lloyd Newson have done beautiful research into the homoerotic ‘clubs’ of men and the masculine culture of pubs. Their dance film Enter Achilles made a lasting impression on me.

J.Z.: The curator Monika Lipšic recently made a comment on social media regarding faulty working methods in the art world, or, as she put it, a ‘lack of mental hygiene’. That is the difficulty of detaching ourselves from our work (for economic and cultural reasons), as well as the inability or even the fear of doing so. The works you have presented in the exhibition remind me of rapid motion from a notebook, and since we can see a repetition of the motif throughout the show, I think about your artisanal practice of drawing on one hand, and the act of drawing them as a therapy on the other. What do you think? How much does this revival of creative power rituals stay within this fictional setting, or do they cross over into our daily lives?

V.B.: Bearing in mind the fact that I am late in answering your questions for the same reasons, I have to admit that it feels slightly awkward to recognise myself and my friends in this comment by Monika. I fully agree with those words, and see myself as a patient recovering sluggishly from this chronic lack of mental hygiene.

The dispute about the therapeutic role of art is an old one, for it is about the autonomy of art, or its political implications. Certainly, every repetitive practice, every cyclical act, has a potential for acting therapeutically, for getting you into a habit, although I would not dare to say that I practise this as self-therapy. This impression might also be nourished by the auto-fictional elements of my story, or by the figure of the Sanatorium itself. It is true that I deliberately make multiple copies of some drawings, which might be a reference to culturally recognisable things, such as Rorschach inkblot tests. But eventually this is a continuation of my artistic practice, born out of intuition and mixed with elements of my artistic research in sanatoriums. I am glad that the Lithuanian Council of Culture awarded me an individual grant for this project.

At some point in the research, I decided to leave out the analytical part of it, and create a piece of art of which a sanatorium would be a part. Sanatoriums have an interesting history: conceived as a medical facility for the treatment of tuberculosis, today what we call a spa is more a part of the broader leisure culture or preventive health industry. I thought about it while watching Federico Fellini’s 8½ and Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad, and reading The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, Summer in Baden-Baden by Leonid Tsypkin, and various essays by Walter Benjamin. It might be a coincidence, but the concept of medical art therapy was developed at the first sanatoriums.

‘Sanatorium’, exhibition view, CAC Reading Room, 2019. Photography: Laurynas Skeisgiela

J.Z.: On the opening night of the exhibition, you did a performance by blowing air into an ‘instrument’ you had created, which, rather than giving out sounds, spat out coloured cotton buds. The apparent sound (or melody, or music) was condensed into a very physical form: a bud connecting fingers and eardrums. Can you tell us a bit more about this work?

V.B.: In the performance, I play a character who narrates his recovery in a sanatorium, and the regaining of the right to make decisions. A cotton bud is the perfect container for metaphors. It immediately places us in the territory of abject theory, which discusses bodily fluids and the physical decay of our bodies. At the same time, a cotton bud also points to our auditory faculties, and the ingenuousness of sounds, stories and voices.

The idea came to me that there is always an ear within a cotton swab, and that even in silence we can talk about the air quivering with some gestures.

I would like to share an extract from the story about the creation of this instrument:

In my room at the sanatorium, not only was there a bed, a wardrobe, and a desk with drawers and a lamp on it. Notebooks, writing pads, a bottle of ink and a bunch of letters which I had just started writing lay on the desk. Letters and envelopes. I was writing the same letters. When I first entered the room, I walked across it and opened the window, and immediately met a gaze, the gaze of the monument to Ivan Pavlov. Then I sat down at the desk and started writing my very first letter from the sanatorium. In this one, which had no addressee, I wrote about impulses, physiology and conditioned reflexes, but unlike Ivan Pavlov, I did not discuss the secretion of a dog’s saliva, or conditional irritants, but a spur which tames the rider, and not the horse.

Letters and envelopes: the perfect title for an exhibition. In the drawers of the desk, I keep empty envelopes, a set of self-medication kits for hypochondriacs, and hygiene accessories. It turns out to be an interesting mosaic of empty envelopes, bandages, medicines, cotton buds and bars of soap. These last came from a special place in Florence, Officina Profumo Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella. I cherish this particular place, because that was where, while still a member of the ‘Order of the Spur’, I experienced my first vision, or to put it more clearly, my first ‘smelling’ experience. There, I recognised myself melting away into the aromas around me. I inhaled them so deeply that I could not even see the boundary between myself and smells any more. It could have been a micro-Stendhal syndrome. This aroma soaked into the scattered envelopes in the drawers, and I quite enjoy thinking about the aroma journeying along the envelopes.

Standing by the open drawer and looking for an empty envelope, I could not find one. In opening and closing it, all the things in the drawer hid in the envelopes, and so became letters. A new order was established. Letters and envelopes. I suddenly had a vision of a cotton bud in the ear and a cotton bud in an envelope; they are the letters, whereas our bodies are the envelopes. A cotton bud, such a trivial thing, soon to be thrown away as rubbish, is one of the things most intimately touching our bodies and crawling into our holes and wounds. In my vision, it became an envelope, and everything that ended up in it, or was found within it, instantly turned out to be significant, even if it was just silent letters. Each cotton bud contains an ear.

A cotton bud is a stick playing syncopes and paradiddles with our eardrums, or it is like a metronome setting the rhythm for a march. An air drummer hits the right notes. I don’t think I’m a very good musician within the spectrum of waves that we can hear, so I try to play with imaginary notes (buds are my notes). Lying down and sinking slowly into my dreams, I decided to create an instrument to play. I jumped out of bed and started looking for material. I found a chip of oak wood and a piece of copper piping that had been lying around since the pipes were changed. With my eyes closed, I pierced the chip with the pipe, and then bent the pipe like a crooked walking stick, or like the sweets they used to lay out on tables at Church festivals. For a while, I imagined ants creeping up these sweets, but I was lucky enough to finally disregard this vision. Then I thought I would try to touch the imaginary strings with cotton buds while playing the instrument, and they would burst in mid-air like confetti, and touch the ground like Mikado sticks or a chance-based partiture. To discern the different timbres and the variations in the sounds, I thought about synesthesia: could it be that someone seeing buds of different colours would hear different sounds? I put watercolours on the heads of the cotton buds, and after trying out the instrument, I realised that the fallen buds, which I previously called notes, had turned into landscape painting.

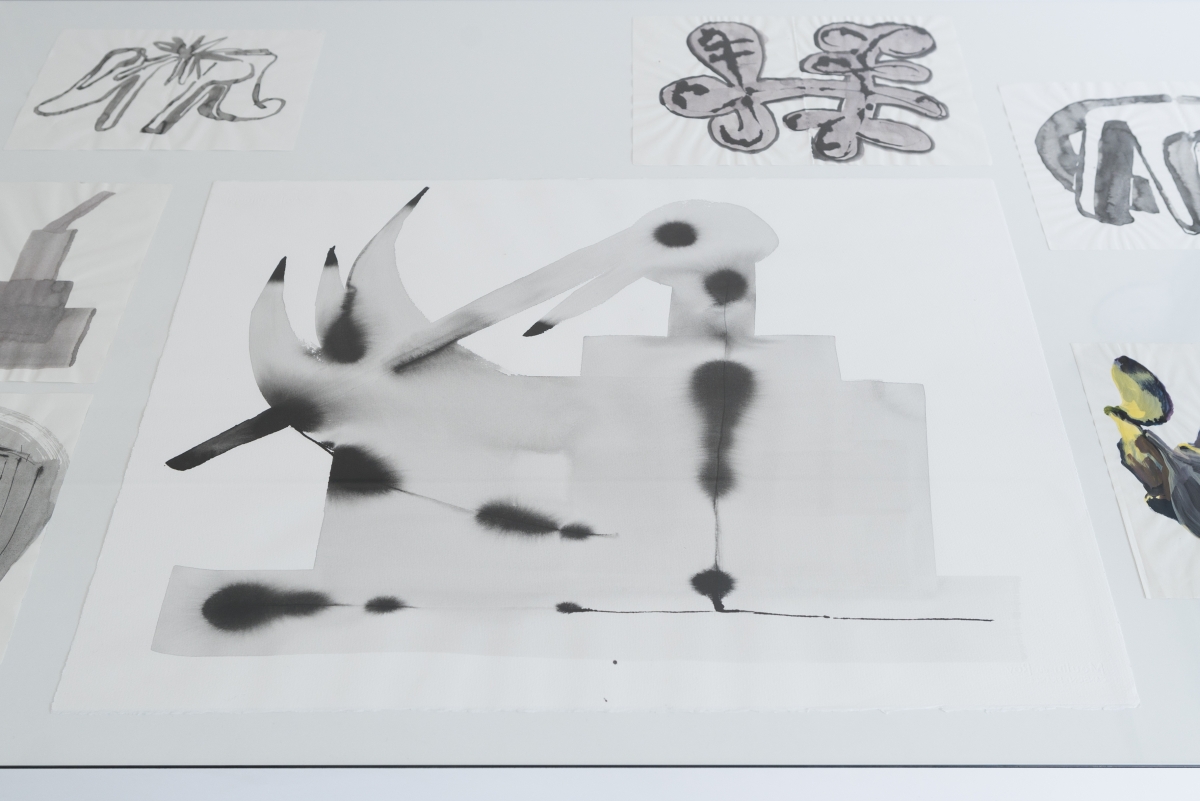

J.Z.: The architecture of the exhibition was born out of conversations with the team, friends and alliances. I well remember discussions about how to retain the functionality of the space (which is a library), but at the same time to let the exhibition wander through it freely. Your drawings were displayed under the glass on the huge work desk in the reading room, and the Xerox machine stood close to the works displayed on the vitrine windows. What did you think about this space and about displaying your work there?

V.B.: You rightly point out that the architecture resulted from collective discussions. I had some ideas, and I was quite sure I wanted to interfere with the space rather gently, and not to transform it by taking away its functionality. The ideas that led towards this exhibition came from literature and texts. But although my intuition set the general tone for it, only boldness in trusting the suggestions of others created the overall image. Here I should mention Virginija Januškevičiūtė, who shared her ideas about spatial arrangement, Laura Kaminskaitė, whose sensitivity helped in selecting and displaying the works, Vytautas Volbekas, who quickly caught the cotton bud elements (or notes) while creating the graphic design for the exhibition, Valentinas Klimašauskas, who had the idea to exhibit some of the drawings in the vitrine windows, and also conversations with Dominykas Liaudanskas, Gianmarco Biele, Ieva Rojūtė, Kristijonas Naglis Zakaras and Vykintas Šorys. I am also grateful to Aleksandras Kavaliauskas, who helped in finding the best framing solutions.

I decided to put the drawings, references to the narrative and various characters’ inner thoughts on paper under one big glass, thinking that it should create a sort of unified visual field. Moments of passing time and entropy have been highlighted by placing some drawings on the windows, which on sunny days cast lazy shadows, just like an hourglass. The Xerox machine that you mentioned was moved to the very end of the space, and was put next to a drawing of a rabbit, which I hope highlighted the sense of reproduction and multiplication I was thinking of. However, this ‘rabbit drawing’ can also be seen as a seated figure with a bow around its neck. It reminds me somehow of David Carradine, a cult figure in martial arts, and the martial arts philosophy. Ceramic sculptural objects with cotton buds, which we talked about previously, landed in my narrative like a sort of landscape painting, a potentiality, a promise of possibility. I wanted to turn the reading room into a sanatorium, drowning in sun and suspended in space and time. I wanted it to be an ellipsis, with an archive of the works from my practice.

‘Sanatorium’, exhibition view, CAC Reading Room, 2019. Photography: Laurynas Skeisgiela

‘Sanatorium’, exhibition view, CAC Reading Room, 2019. Photography: Laurynas Skeisgiela

‘Sanatorium’, exhibition view, CAC Reading Room, 2019. Photography: Laurynas Skeisgiela