Miglė Markulytė: At the present time, your art works can be seen in two venues of the Baltic Triennial: that is, your exhibition ‘Feed’ in the Editorial space, and the mural and short movie ‘From the Heart’ at the Contemporary Art Centre, as a part of the main triennial exhibition. How did that happen?

Anni Puolakka: I had already been preparing for a personal exhibition at Editorial, when I was invited to exhibit work at the CAC. When Valentinas and Joao invited me, I had mixed feelings about showing work in two places at the same time. I was wondering what the relationship between the two exhibitions could be. For the show in Editorial, I had a chance to select every detail and form the general setting myself; whereas the work for the CAC was chosen together with the curators, and became part of a large group show. From the Heart is my most recent video work, while the show in Editorial encompasses a bigger time-frame of my practice. It comprises works made during the past four years, as well as completely new ones. When preparing for the exhibition at Editorial, I took the chance to focus more on painting, which became my daily routine. That also transmitted to the exhibition in the CAC: I had the idea to paint a mural.

MM: There is clearly a conceptual conversation happening between these even spatially close exhibition spaces. It’s not only the distinct colour red, which permeates both settings, but also the topic of human relations with other living creatures. How do you see those relations yourself?

AP: All the work is about how our existence takes place in different relationships. For example, in the video From the Heart exhibited at the CAC, a parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, lives inside a human, their bodies are entangled. Creating the video, I was interested in challenging the idea of ‘self’, and posing the question whether another organism living in your body could be part of what you consider to be ‘you’. Toxoplasma is not something you can get rid of: once they are in you, they are there to stay.

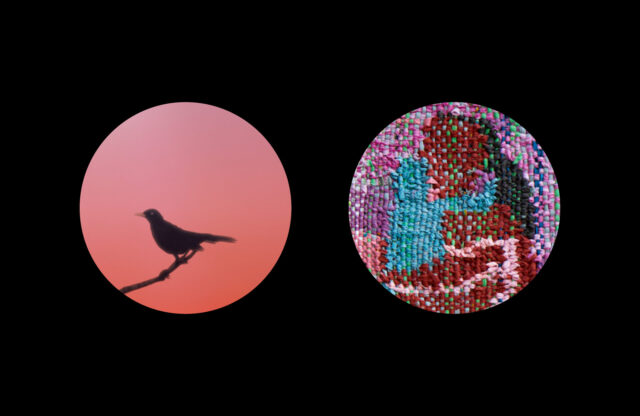

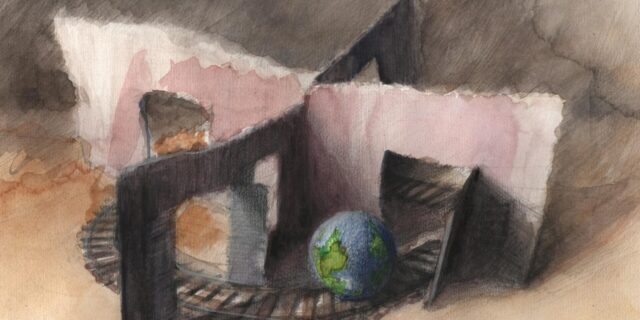

Exhibition ‘Feed’ by Anni Puolakka at Editorial, 2021. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

MM: But the work Rumina at Editorial also talks about a cow entering your body when you’re consuming its milk?

AP: Yes, the video addresses the origins of milk, a thinking and feeling body that’s similar to the human body in many ways. I wanted to expand the typical notion of suckling, and see how it changes when explored against different contextual backgrounds.

When somebody talks about suckling or breastfeeding, the image that usually comes to my mind is a mother with a baby. In creating the video, I wanted to focus on other breastfeeding scenarios. I explored the history of representations of suckling, and also looked into how robots milk cows on modern farms. If you look at children’s books, there are farmhouse pictures that seem to be from the last century, not reflecting the industrial reality. There are lots of aspects missing from the pictures, like how calves are separated from their mothers, and how cows are slaughtered when they stop producing milk. And these are not just missing from children’s books, but also from our consciousness and our language when we consume dairy products. There is a great article by Melanie Jackson and Esther Leslie called ‘Journeys of Lactic Abstraction’, which represents milk as one of the most technologised, capitalised and abstracted liquids on earth.

MM: So the shift of spaces also shifts the position of an individual, or the whole species, in the feeding circuit. It reveals that a predator is also a prey, but then what is a parasite?

AP: The idea of a parasite is a construct reflecting the human perspective. We classify Toxoplasma gondii as parasite, but then, could this term be shifted? I find it meaningful to play with the idea of humans as parasites for cows. Word-created classifications are deeply rooted in our everyday language, and for me art is one of the ways to question them, or to create situations which allow us to go beyond imposed binaries, between, for example, humans and non-humans.

In creating the video (From the Heart) about Toxoplasma gondii, I collaborated with a scientist, and we talked about the word ‘parasite’. In Finnish, isäntä, the word for ‘a host’, is gendered, and related to the word isä, meaning ‘a father’. We were trying find a word that would be non-binary, and therefore we came up with the word majoittaja, which literally translates as someone who accommodates (maja means ‘a hut’ in Finnish). It is exciting to push the limits or loosen the strict categories of language, which represent normative concepts.

MM: I believe it takes great ingenuity to break out from conventional constructs, but how do you create such stories? The narrator in Rumina seems very honest when talking about their relationship with cows, but then the scenario deviates to a clearly imaginary situation. Diamond Belly, which touches seemingly personal, sexual topics, also turns out to be a conversation with the chatbot. This makes me question the border between autobiography and fiction, and how these two positions are combined in your creative process?

AP: In every work, there are aspects from my own life that touched me and became an inspiration for the work. I use these experiences or observations as a starting point. I write them down, and then develop them into fictional stories. For example, writing the script for From the Heart, I decided that Toxoplasma gondii, played by a human actor, should be the protagonist of the story, and this idea already brought the work into the realm of fantasy.

Or sometimes, even when jotting down my personal experience, I already use fiction. Usually, characters become the driving force. Yet even though fictional, to some extent they might reflect me. But do you think it makes a difference if the viewer knows what is real and what is not?

Exhibition ‘Feed’ by Anni Puolakka at Editorial, 2021. Photo: Ugnius Gelguda

MM: Well, I feel it changes my point of view if I think that the story is about the author, or when I have someone to associate it with. Yet your mainly collaborative practice seems to be dissolving the borders of an artist as an individual, but the voice in your videos is still talking from the first perspective. So what does the ‘I’ in your work stand for?

AP: Well, I enjoy experimenting with different perspectives. Sometimes I use my own body to perform; sometimes I ask somebody else to do the voice-over, like in the video about mosquitoes. That story had to be told from the ‘I’ perspective, because it’s made in vlog style, talking straight to the camera. I was inspired by the aesthetics of Youtubers, which I find fascinating and powerful. I believe it is a very good way to engage viewers, when it seems that somebody is telling you their story. Yet in the context of art, it becomes a different situation, and helps to break out of the container of who is you.

MM: Your practice also seems quite interdisciplinary, bearing in mind video pieces that are born out of performance, not as a documentation but as an extension, like the same topic gaining another, more sustainable, longer-lasting body. What do you think happens to the art work when it is reduced to only one form of expression, like Rumina, which was originally presented alongside a performance?

AP: For me, it is important to use several media to deal with topics. I think that they feed each other and provide new viewpoints on certain topics. Performances help me to generate ideas and material for video production, and vice versa. Sometimes I incorporate drawings or images into my videos, so I find it exciting to mix media. But being present, as in a performance, creates very different kinds of sentiments to making or showing videos, which is a more mediated experience. Sometimes I envy artists who are very contained in their practice, who are committed to a certain method, and master it; but that’s not my way, I tend to burst out in all directions.

When asked about what she had been feeding on while creating these works, Anni recommended three books and wrote short reviews about them. You can find them here