Goda Klumbytė is an interdisciplinary scholar working between informatics, humanities and the social sciences. Her research engages feminist new materialism, posthumanism, human-computer interaction and algorithmic systems design. In her doctoral research, conducted at the Gender/Diversity in Informatics Systems group at the University of Kassel, Germany, she investigates epistemic premises of machine learning as a knowledge production tool, and proposes innovative ways to work with intersectional feminist and new materialist epistemologies towards more contextualised and accountable machine learning systems design. She co-edited More Posthuman Glossary with R. Braidotti and E. Jones (Bloomsbury, 2022), and has published work in Posthuman Glossary (Braidotti, Hlavajova, 2018), Everyday Feminist Research Praxis (Leurs, Olivieri, 2015), and the journals Online Information Review, Digital Creativity and ASAP, as well as participating in informatics conferences such as ACM’s CHI, nordiCHI and FAccT. She is one of the editors of the critical computing blog https://enginesofdifference.org.

Tautvydas Urbelis: Hello Goda, I recently received a question about conducting an interview with you. My calendar was brimming with tasks, meetings and notes of desperation; however, I could not resist the temptation to have a conversation with you. I find it such a stimulating experience, and I wanted to share this pleasure with readers as well. So how are you doing these days?

Goda Klumbytė: Hi Tautvydas! You caught me at a similarly busy time. I am subsumed in dissertation writing, with the hope that I can put most of the other tasks on hold and finish this monstrous project this year. Doing one’s doctoral work is just such a specific time in life, punctuated with intense moments of both pleasure and the agony of writing. I’m also working on some editorial projects, some of which have just been published recently (a special issue of MATTER on New Materialist Informatics), some of which are due to come out soon (More Posthuman Glossary, co-edited with Rosi Braidotti and Emily Jones), and some that are still in the works. All the while, I try to remind myself to go out and enjoy the sun occasionally too.

Screen grab from digital artwork by MELT (Ren Loren Britton and Isabel Paehr), courtesy of the authors. http://meltionary.com/MELT.html.

TU: Pleasure punctuated with agony sounds like an oddly seductive feeling that, I assume, is reserved solely for those who dare take up the task of dissertation writing. Speaking of which, maybe you could say a bit more about it?

GK: Pleasure and agony might just be a part of the writing process in general. But yes, academic writing, and specifically the dissertation format, is its own kind of thing. I am working on something interdisciplinary, which adds further complexity to it. In broad terms, I am trying to raise some questions about the epistemology of machine learning algorithms. If we agree that machine learning algorithms generate knowledge, what kind of knowledge is it, and what are the principles of its production? In other words, how do machines know, and what do they know? I also want to see how, if at all, machine knowledge can be done differently. I am interested in algorithmic bias that plagues these systems, or rather, now we even speak of algorithmic harms, and not just bias, and where it comes from. The usual narrative is that algorithmic bias comes from bad data, and if only we had better data, our problems would be solved. But, coming from the background of media theory, I think there is also something about the logic of the technological tool itself and its operations that impacts its shortcomings and sets its limits.

To be more concrete, I am looking at the operational logic, histories and discourses of several simple machine learning algorithms, and trying to understand what these algorithms are, what kind of stories they figure, and what logic they enact. In this respect, my work is situated in science and technology studies and critical algorithm studies, because I am interested in machine learning as a techne and its impacts. That’s the first part of my work. The second entails looking at how machine learning systems can be figured differently with critical tools from feminist intersectional work. If it’s clear that algorithmic systems enact, reproduce and exacerbate structural inequalities, what might happen if we try to design them with feminist intersectional critical tools? In this respect, my work resonates with calls for intersectional computing, decolonial computing and the development of critical technical practice that have been expressed in computer science communities.

TU: Oh, so much to unpack in your answer! I am intrigued that your research probes beyond the argument bad data equals bad algorithms. I think it is a very deceptive line of thought, because on one hand it usually admits that bad data comes from people plagued with racism, sexism, ableism and other prejudices; on the other hand it presupposes some sort of technological purity, where technology only reflects human knowledge like a high-definition tabula rasa. Not to mention that this techno-utopian innocence also throws out technological solutions left and right, undermining often deeply rooted, systemic causes of many of the socio-political and ecological problems that we face today.

GK: Yes, the idea that technology is neutral as such is very strong. I think there are two aspects to it. On one hand, technological innocence, technology as a blank canvas. There is, of course, some truth to it, but more in the sense that technologies have certain proclivities and affordances that can be put to many different uses: the tools we use are not entirely pre-determined in terms of their function (that’s why we can talk about appropriation, hacking, jamming and repurposing practices). But on the other hand, the second aspect that emerges in the idea of technological neutrality is that technologies somehow have no history, no agency, and, most importantly, that technologies are something radically opposed to things that do have history, agency and culture, i.e. humans. But of course, all technologies come from somewhere, and carry histories as well as presents with them. Konrad Zuse, the famous German engineer, for instance, talked about computing machines as ‘embodiments’ of mathematics, materialisations of thought. I see technologies as their own relational socio-technical things or beings. They have histories, they have agencies, they are entangled with culture and thought, in that they are also enmeshed with more-than-human cultures and are active parts of more-than-human environments. I use specifically ‘more-than-human’ here because they entail other technological and biological beings, and not just humans. Some interesting people to think here with would be the French philosopher Gilbert Simondon (1924-1989), who talks about technologies as individuals, or rather about technological individuation and genesis as active processes. But one can also think about this with other relational philosophies, and especially with indigenous philosophies that manage to encompass natural, cultural, technological and economic worlds and their complexity with more care and nuance. For example, the article ‘Making Kin with the Machines’, by Jason Edward Lewis, Noelani Arista, Archer Pechawis and Suzanne Kite, explores how to account for AI and other smart technologies in indigenous world-views.

So, yes, complexity is important in understanding, and hopefully responding, to the changing landscape of the contemporary world where technologies, as Donna Haraway said, are so alive and humans sometimes look so inert …

TU: Allow me to be a bit provocative and say aren’t we falling into the trap of an uncanny valley when imbuing technologies with agency, history or culture, qualities that often assert the dominance of anthropocentric world-building? Of course, none of those qualities belong solely to the human domain, but maybe to fully recognise the agency of technology we need radically different conceptual frameworks? I am thinking here of different xeno–practices, especially the emphasis of alienation as a creative potential that doesn’t rely on pre-existing patterns.

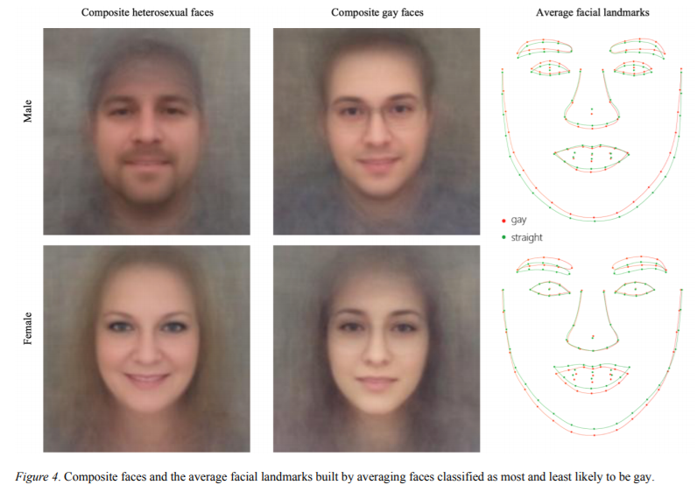

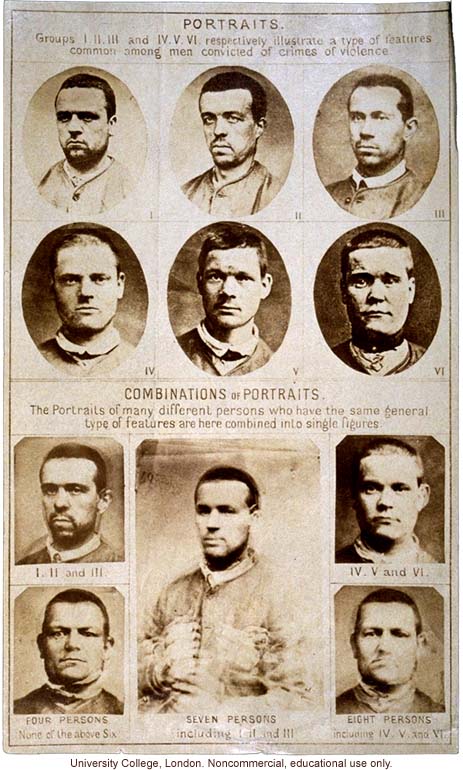

GK: Well, I guess it depends what your end goal is, what is the reason why you are looking into technologies and their agency. After all, concepts are pragmatic instruments, and not some sort of ultimate platonic ideal. I love the work of xenofeminists, and I think it is good to think about alienation as a way to distance oneself from anthropocentric forms of knowledge production that always revolve around the benefit to the human, where the human is equated with the image of a white, European, able-bodied, cis-gendered, middle class man, as Rosi Braidotti so brilliantly shows. For my own work, however, I am interested in relationality, which means that I am interested in what happens at the meeting points, and how these meeting points reconfigure the very entities involved. For this, recognising the differential agency that entities have is important, particularly when the effects of those re-configurations affect different populations differently. For instance, who gets to marvel at technological otherness and explore the potentials of technologies, and who becomes ‘test rabbits’ of the workings of these technologies? The history of Western science and technology time and time again shows that it is the bodies and lives of the marginalised, racialised, naturalised, sexualised others that become the loci of experimentation and exploitation (for instance, see the work of Francis Galton, eugenicist and father of modern statistics, whose composite photographs trying to capture ‘the criminal type’ are eerily similar to the, fortunately discredited, images produced by the so-called ‘AI Gaydar’ that is supposed to tell from a photograph if a person is homosexual or heterosexual). New technologies, historically and today, tend to get tested on disenfranchised, marginalised, peripheralised communities first (think of Facebook experiments with news feeds, and how that affected smaller publishers in Eastern Europe, or their meddling with elections in Kenya and Nigeria before Brexit and the US elections in 2017). Ruha Benjamin and Simone Browne explore this in depth with regard to racialised communities. In other words, I am interested in agency and its differential variations also because this allows me to think how these agential forces are constrained, restrained, opened and enhanced differently, depending on the locations and power dynamics. Agency, as I understand it, is profoundly relational.

Composite portraits from Kosinski & Wang’s infamous paper (2017) that claimed to produce what has been coined “AI Gaydar”. The paper was heavily criticized and its results discredited as relying on flawed premises. Nonetheless, classification based on facial images persists.

Composite portraits showing “features common among men convicted of crimes of violence” by Francis Galton, with original photographs, circa 1885, University College London, GP, 158/2M.

TU: Indeed, it seems that recognising the relationality of agency is a crucial step in recognising the intersectional nature of many exploitative practices, often exacerbated and simultaneously obfuscated by technology galore. Speaking of intersections, the first time I encountered your work first-hand was during ‘(a)symposium on (various) matters’ in Kaunas, where you, together with Ren Loren Britton, facilitated a workshop on embodied algorithmic reading. Later, our paths crossed when you facilitated a workshop for Rupert’s Alternative Education Programme, introducing some key ideas in posthumanism and new materialism. Both of these events were closely or directly related to art that so often draws inspiration or directly works with theory and philosophy. Can you tell us about your relationship with art and artists; and do you think there is space for artistic research/sensibility in academia today?

GK: I think art is tremendously important for the exploration of the kinds of agencies and techno-worldings that are emerging. Art for me is a space where imaginaries, forms of subjectivities, technologies of relation, are built, explored, dismantled, challenged and recombined. Ren and I wrote collaboratively on the convergences and divergences between art and computation, for instance by exploring the role of abstraction in art and computing and how various practices of translation can position abstraction as an affirmative practice of relation-building. We also explored how working with artistic research and techno-feminism can help re-configure methods and practices in computing. We also practised together a kind of open and playful speculation on what computational entities could look like if addressed through a relational lens. Art is a research praxis in its own right, and a very important one, because of the kind of space for experimentation that it allows, and the kind of open modes of research and expression that it generates. There is a lot to be said about the institutional politics of this, of course, what it means to have some kind of research degree such as a PhD in practice, but I don’t think I can speak of that succinctly, as I am not an artist myself. But what I can say is that for me as an academic, collaborations with artists are important, because of the experimental ethos that these collaborations are often built on, where artistic practice and academic practice interact and intra-act with each other. But again, it’s important to set the premises of these collaborations in such a way that this intra-action becomes possible. As you probably know well yourself, there are power dynamics at play in such cross-disciplinary collaborations (whose funding is supporting the collaborations? How are the funds distributed, and to whom? What institutional settings are supporting collaborations? Is artistic output sufficiently valued and on equal terms with academic output? Whose modes of working are taken as the baseline? etc), and they need to be at the very least addressed, and often challenged or disrupted, for this to work.

TU: Well said. I think these questions are steadily gaining importance as part of artistic inquiry in their own right. My last question is about scale in an increasingly uncertain and complex world. Some of the premises, processes and findings that you talked about during the interview are fascinating, but at the same time can feel overwhelming, more-than-human worlds, agency of technology or operational logic of machine learning, ideas that tackle relatively new but already fundamental questions of Anthropocene. However, you actively seek to step outside academia, and with the help of often collaborative workshops show that a lot of research and positive impact can be done with seemingly simple gestures: collective reading, gathering and listening. Can you tell us how you navigate these different processes, and how complex theories can help us to live in a complex (and damaged) world?

GK: I assume your question here also references ‘Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet’ (2017), edited by Anna Tsing and others, which offers reflections from many different disciplines on how to live, care, imagine, and act in the Anthropocene. This is a broad ethical question, a question for a lifetime. There are at least two dimensions to it, or two ways of answering it: one has to do with methodology, and one has to do with personal ethos and decisions (and, of course, these two ways are not separate from each other). Methodologically, for me it’s all about finding ways to translate broader theoretical insights into practices, finding, or actually rather constructing, adequate methods. As you said, it can be small shifts: noticing the non-human in one’s practice, in one’s research, noticing the non-unitary character of whatever topic or subject one is exploring, noticing the collective dimension of one’s work (and there is always some collective dimension, even in spaces as individualist as academia), and then acknowledging this multiplicity of agencies in ways that make sense for one’s practice. So, for instance, for me this means asking: how can I approach my topic (machine learning) as an assemblage? How can I disrupt the disciplinary hierarchy when it comes to who has a say in designing those assemblages? How can I account for the environmental, world-making dimensions of those assemblages? How can I create and maintain conditions for collaboration in exploring those assemblages? Who am I doing this for?

Of course, this also means being aware of my own position, and making decisions about the kinds of ethical questions that I find important. Also, the theory is not so detached from life, but rather I find it is of and in life, it is a way to make sense of life. As Arianne Zwartjes notes in an article on autotheory, which is a kind of way to bring the personal, political and theoretical together: ‘What does it look like to “metabolize” concepts directly out of one’s lived experience […]? Or, in Sharpe’s conception of “theorizing through inhabitation”: how do we take these metabolized concepts—these new ways of knowing—and “live them in and as consciousness”?’ I’m really interested in this idea of metabolising concepts as a process through which theory makes sense, i.e. becomes part of new sensoria (McKenzie Wark). These sensoria are embodied, embedded, they are a product of locations (Adrienne Rich) that do not offer grand perspectives, but something much more important: ways of collaborative survival.

TU: Thank you so much Goda. As always, it is such a treat to speak with you! Lastly, can you let us know your immediate plans, and what kind of feeling you are going into the autumn with?

GK: Autumn is always a busy time for me, but also very productive. Right now, the main plan is to finish my dissertation, and then start a new project on AI Forensics. Generally, I try to stay with the feeling of realistic, careful hopefulness. This takes some effort to maintain, and I often question what it is I am doing, and what it is I should be or could be doing, especially in the context of the invasion of Ukraine and the environmental devastation that is constantly intensifying. On the other hand, this questioning is something that might be necessary for keeping that realistic part. So yes, careful, grounded hope.

Electronic Waste at Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Image source: Wikipedia.