Recently, I keep getting ‘stuck’ in clay: it seems that attention to ceramics is increasing, and not only among those who want to make a handmade item, but also in the professional field, among creators, art critics and curators. So when interviewing ceramicist Monika Gedrimaitė, I had quite a few questions about the conceptuality, functionality and the growing popularity of the field, the community of ceramicists, and, of course, Monika’s own creations and inspirations. Monika Gedrimaitė (b. 1990) is a ceramicist and a member of the Union of Lithuanian Artists. She has a BA and an MA in ceramics from Vilnius Academy of Art, and also studied at the Estonian Academy of Art. Her works have been presented at more than 20 group and personal exhibitions. Monika recently moved to a new studio, where, as she mentioned, she often immerses herself in reflections on cultural ecology: what works are needed, and why?

Monika Gedrimaitė. Photo: Fausta Genienė

Agnė Sadauskaitė: You have been involved in professional ceramics for more than ten years. Tell us how you chose this area, or, as you often ask in interviews that you conduct, ‘where did you come from, and where are you now’?

Monika Gedrimaitė: I started art school quite late, but I was still determined to prepare for the entrance exams to Vilnius Academy of Art. I studied painting, sculpture, ceramics and academic drawing at an art school, so my educational field was quite rich, covering many areas. At that time, I did not think I would study ceramics. When I was preparing my thesis, I was interested in many things, my creative thinking was influenced by Jonas Mekas and the Fluxus movement. For my final work at the art school, I wrote a script, created and edited a video, painted large-format paintings, and invited my friends, with whom I organised a paper airplane workshop, and we created a performance in all this tangle. Meanwhile, a friend at the art school was sculpting a tableware set from red Lithuanian clay for her final project: she would come in and would know that she would make sculptures that day, and when they would be finished. In my creative work, I didn’t know when my project would end: I had many ideas and quite a few solutions. However, I think I listened to my inner voice a lot, and had a lot of self-confidence. So, out of a desire to create an environment, an atmosphere, after school, I imagined myself studying scenography. However, I remember how I was afraid of one professor’s intimation during the admission procedure that I would not get in, and I got a lot of criticism for my portfolio. However, another teacher, after seeing my ceramic work, took me to talk with the teachers in the Ceramics Department. They suggested I try to enrol in ceramics, in which I succeeded, but I enrolled with the idea that I would try my best to switch to scenography. However, during my ceramics studies, I got on well with my coursemates, and I was also fascinated by the idea of diving deeper into a specific art form. So I replaced studies about the environment with studies about an object. So that’s how my journey began. I started studying ceramics in 2010. I founded a ceramics studio with colleagues and started to work independently in 2015. And I started my MA in ceramics in 2016.

AS: Are you planning to continue your studies?

MG: This autumn I seriously considered starting a PhD. In the spring I went to Tallinn, where I prepared a theses, and wrote what my doctoral project would be about. But the summer was so much fun and passed so quickly, and in the autumn I started renovating the new studio, and I put the notes in a drawer and postponed the plan for an indefinite period. A number of life-changing events have happened that I still want to come to terms with. I still have unanswered questions about how I want to approach my work at an academic level, and what kind of community I want to create from it. This decision really takes some time.

AS: Was mastering clay as a material a difficult process?

MG: I had tried it before my studies. I managed the material quite well, even though we didn’t have a large arsenal or access to one at Skuodas School of Art back then. We worked with only a few types of clay, and the main base glazes. At the Academy, the studies became even more involving, because a new technical base opened up: a laboratory, different types of firing, and various clay masses and production techniques. Many complex processes take place with the materials, and conceptual ideas also appear, in ceramics. Over time, I think every potter discovers their own area in which they decide to expand. I’m really enjoying the process of the material right now, because it finally doesn’t seem so complicated any more.

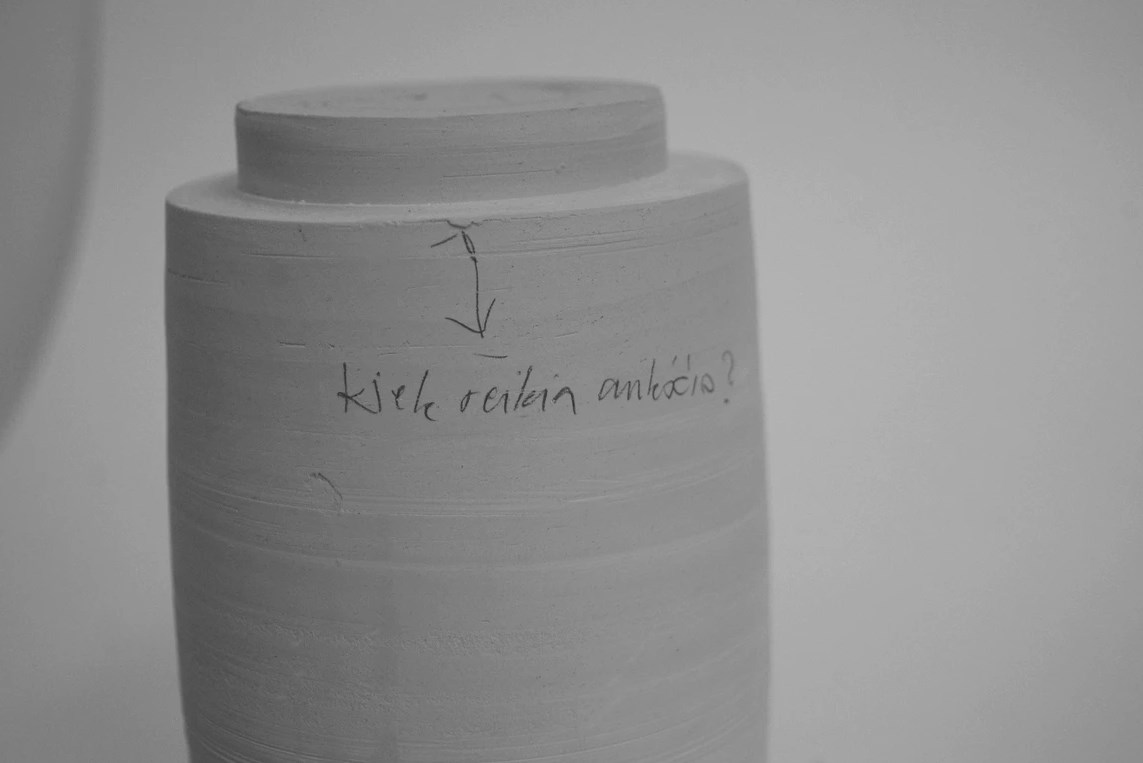

Exhibition, How Long does Creativity Last. Photo: Ingrida Mockutė – Pocienė

Exhibition, How Long does Creativity Last. Photo: Ingrida Mockutė – Pocienė

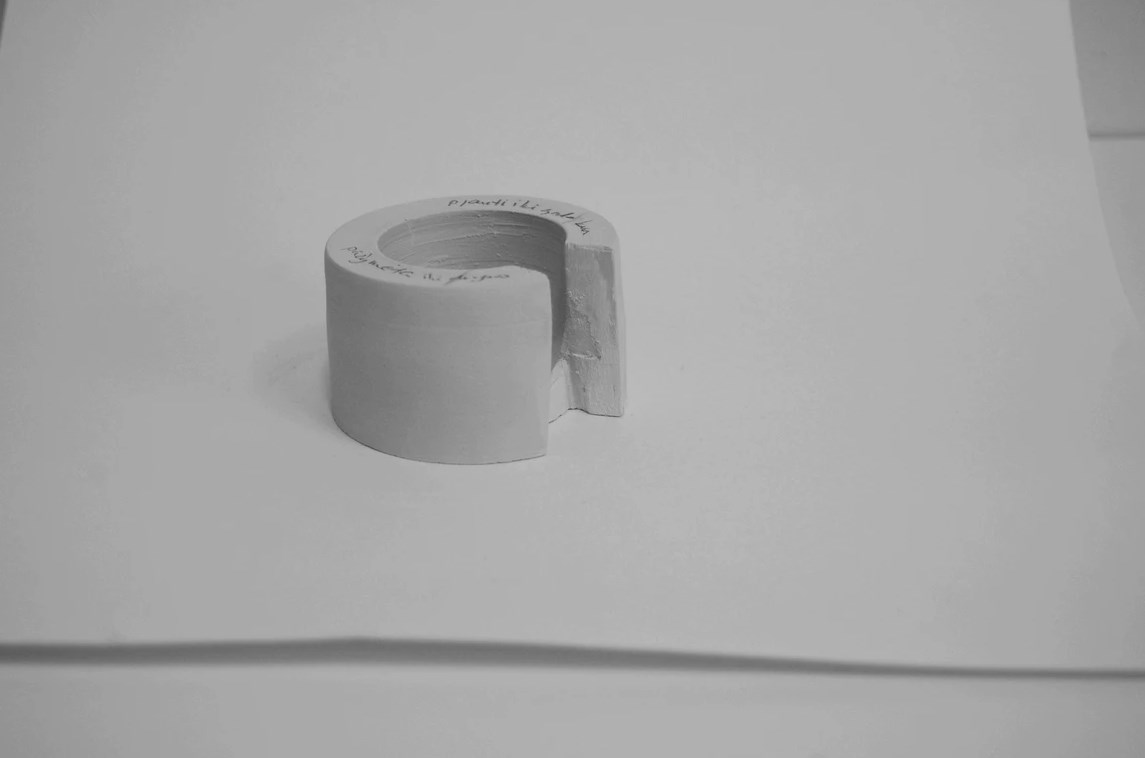

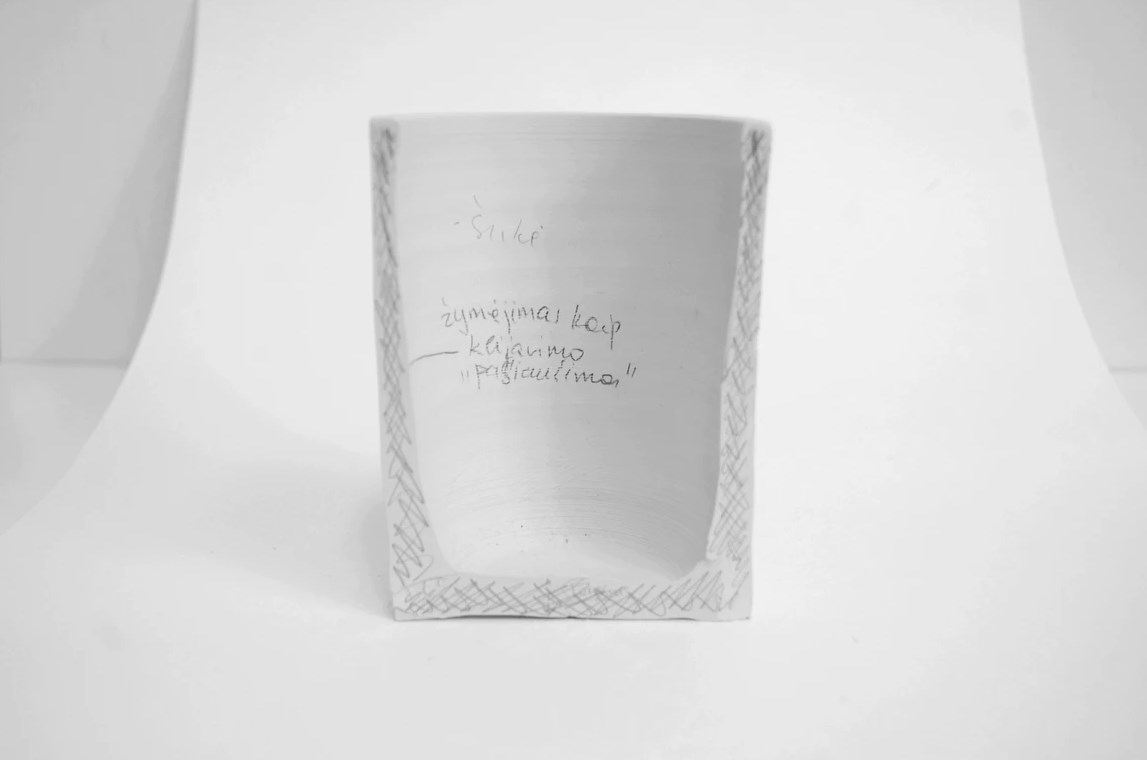

AS: In your work, there is an emphasis on a few aspects: the essentiality of an object, variants of its purpose and new ways of presentation, reduced function, and the identification of objects. Tell us what interested you about this topic, and what discoveries it brought.

MG: I discovered this topic during my MA studies. In my first year, I started making small-format cylinders, similar to cups and vases. Eventually, they turned into various puzzles, or compositions. I hung them on the walls, and began to observe how the shape changes in different concentrated spaces. Once I took one of them and split it in two with a hammer. It was a small bluish object that could have served as a container, but something happened during this act. It was not just the vessel that opened, but my understanding of it as well. Then I started cutting more, cutting the finished objects with various saws and other tools. It seemed that each time, a new meaning to the vessel-item opened up. I didn’t see it as a ceramic vessel, but more of what the abstract object is made of. The vessel/object remained the same, still independent, but my intervention, cutting or beating, became a reflection of it, touching but not changing it. It is from here that the reduction of the object, and later deconstruction, arose. I decided to choose an object that would have no context, history or quotations. The thing happened by itself, and the original idea was to understand what it was made of. After cutting the object, you can see how thick the walls are, the characteristics of the clay, the particles of the material. It was then that the independent materiality of the work opened up for me, a being that already told of another authentic function.

AS: When considering the materiality and function of the object, you say that you experimented. So I wonder what turned out to be more important in the end: the concept itself and the contemplation around the object, or the expression of the idea?

MG: I don’t have an unequivocal answer. I feel that the very expression of the object is important to me, so the answer seems to be the object and the material. However, at the same time, I feel that I should tell you why, which would take time. So in my case, sketches, experiments and working with clay are intertwined. I start the shape on the wheel, and in the cutting action, like sketching on paper, I see which side interests me, and how I can expand it. The process is always interesting, but it’s a shame that I don’t know how to enjoy the discoveries in the process, because they are often most clearly visible at the end. This is also determined by a certain technicality of ceramics, when the next normal stages develop: drying, sanding, firing, decorating and glazing. I think that during these processes, I continue to develop sketches and capture them. However, when I manage to look at the process, I often realise that there is a lot of value hidden in it. My understanding of what the conceptuality of ceramics and what the result is come from each other.

AS: You recently shared an article about ceramics and wrote a short comment stating it seems that a lot of ceramicists are stuck in the technique. I wonder how important experimentation and finding new ways are to you?

MG: I see a correlation between technique and experimentation in the question; however, I believe that experimentation does not always coincide with ceramic technique. For me, experimentation is the alignment and junction of incompatible disciplines. However, I would consider the experiment a failure if there was no purification and some knowledge in the long run. Experiments are a rich brainstorming session, but you need to learn something from it, and not just create something without even understanding what you have created. Experimenting for the sake of experimenting and its results seems unsustainable and short-sighted to me. So that’s what I mean when I say that sometimes ceramicists get stuck in the technique. Of course, those discoveries often look amazing, but why is not very clear to the creator himself. Sometimes, after mastering proprietary or traditional techniques, it is difficult to get out of them, they do a disservice, and there is less and less original thinking.

Exhibition, Uola ir vėjas. Erdvės objektuose. Photo from personal archive

Exhibition, Uola ir vėjas. Erdvės objektuose. Photo from personal archive

AS: In 2020 you had the solo exhibition ‘Rock and Wind. Objects in Space’ at the Arka Gallery. During it you also carried out a ceramics performance, in which you made three clay objects in the gallery space. That also seems to me like an experiment. How long did the performance last?

MG: The exhibition consisted of two parts. One part was so-called finished sculptures, that is, moulded and fired, and the other part was performative moulding. This was my approach to ceramics about ceramics, made with ceramic composition, but not the technique. The performative part was my conversation, trying to talk to others about ceramics, the composition of ceramics, but not completely technically. During the performance, it was as if I had walled myself off and dived into a common ceramic object, a vessel, and the event became a continuation of it. I call this movement a kind of scissors that dissect the discipline in which I create. Technically, I probably did it well, but I did not fire or glaze those works; it was not necessary.

The moulding itself took two or three weeks. I came when the gallery opened and left at around 6pm. I made the works during the exhibition, and the visitors who came first viewed the exhibition of paintings on the ground floor, and then went up to the first floor where mine was taking place. When they saw the whole ‘construction’ environment, the piles of clay and me working inside, they were surprised and apologised for disturbing me, thinking that I was just preparing. But then the moment of discovery happened: I invited them to stop, inspect the works, and told them about my ideas.

AS: So how did it feel to crawl into the vessel and almost be sealed inside it?

MG: It was a lot of fun. I was happy with this idea. However, I had to hurry at the end, because I was about to leave for a symposium. I had to finish the sculptures, so there was a bit of stress. I had planned to use almost a ton of clay for the three sculptures, and planned how much space they would take up in the gallery. One object was like a rock that could fit around ten to fifteen people. I made another smaller object: it was a wall with textures; and a third object, a column about 180 centimetres high and almost a metre in diameter. I had thought about these objects before I started working, but in the process, managing such a quantity of clay turned out a little differently to how I had planned. The goal was also to observe how the sculptures changed throughout the process. I had cameras and recorded the whole process, keeping in mind that it would become a separate artwork, not just a documentary. Later, I presented the documentary in the form of a short video at other group exhibitions of ceramics.

AS: At the end of October 2022, another personal exhibition of yours, ‘How Long does Creativity Last’, opened at the Baroti Gallery in Klaipėda. In it, you exhibited clay sculptures in various shapes, sizes and colours on wooden pedestals you had created, combining the works with texts in which you shared your childhood memories. When speaking about this exhibition, you emphasised that the most important thing in the process is the sensitive look at the environment and your own experiences, while the concept of ambivalence becomes the leitmotif connecting your works. Can you tell us more about this?

MG: I feel that ambivalence has been one of the leitmotifs since the beginning of my work. I think the first time I heard the term was in a chemistry class, and even then it seemed close to me. I like to work between opposites, to search for new languages in them. The idea of the exhibition, the guiding phrase ‘how long does creativity last’ came up a little over a year ago, when my colleagues and I were preparing a project relating to artists’ copyright and related rights. We interviewed ceramicists about their creative activities for which they receive remuneration, and what their working day is like, what they usually do in their studios, how long it takes them to make a piece for an exhibition or a commission, and so on. Many shared what the viewer doesn’t usually see, what lies behind the final piece created. By recording the artists’ speeches, a video message was created, with which we aimed to show people what they do not see when looking at a work. Because of this, artists have to deal with a lot of domestic, physical, financial and emotional aspects that are usually left behind the scenes.

Returning to your question about the exhibition, I imagined that when preparing for a solo show, I would document exactly those domestic aspects, invisible to everyone: how much it cost me to pay the rent and electricity, how much water I used, how many hours a day I sat with the works, how many kilograms of clay and glazes I used. I imagined then that it should be quite poetic. However, the rational presentation of accounts, numbers and graphs turned out to be too discouraging for my state of mind at that time, so I naturally moved towards where my intuition and heart sensitively led me. When I started listening to this part and what it was telling me, I looked back at my childhood, at memories of what I used to do in my free time. And my memory was about how I used to walk and collect beautiful pebbles in interesting shapes. As a child, I was an observer. I spent a lot of time alone, exploring the world, climbing trees, doing woodwork in my grandmother’s woodshed. Those pebbles and the experience of working with wood became works in the exhibition, relics from memories. I understood and felt that the rediscovered sensitivity to the environment was always there, and still is, but I had somehow forgotten it. It helps me learn about the world and create things. You need to listen to this quality, and not be afraid to use it, even if sensitivity is often understood as a negative quality in a world where you often have to defend and fight for yourself. So the creation process lasted until I had covered all the aspects mentioned.

Aesthetics of a vessel: from thing to art. Photo from personal archive

Aesthetics of a vessel: from thing to art. Photo from personal archive

AS: So this exhibition was one of the components of normalising the rediscovered sensitivity, and at the same time a very personal experience?

MG: Actually yes. I had a lot of fun creating the works for the exhibition. I made a lot of memories walking around my home town. I thought less about the ceramic materials themselves, and more about being myself, and I really appreciated that.

AS: I have noticed that you also incorporate writing into your creative practice: you conduct interviews with ceramicists, you post them and other texts on your website, and excerpts on your social media account. Why is it important for you to talk to your colleagues and reflect on ceramics in writing?

MG: Writing is definitely something I have yet to master, but the very idea of interviewing ceramicists came from an increased interest in the field, and a desire not only to introduce people to my work, but to speak and expand knowledge about the field of professional ceramics. I met the artists I interviewed at a ceramics symposium. They are all very different, but we worked together: we fired the works in an anagama kiln. This kiln and the firing technology somewhat unify the works; but the different approaches of the ceramicists to form and style still remain. During the interviews, it was interesting to hear how each ceramicist works, what their vision and thoughts about ceramics are; and at the same time it was interesting to find out what the difference is between different generations. Potters like to be alone in their studios with their clay, and I wanted to get them out of it.

AS: Did you manage to get ceramicists out of their studios? Can you feel there is a ceramics community when conducting interviews and participating in symposiums and exhibitions?

MG: There certainly is. Due to the peculiarity of associating the work with a specific material, ceramicists are individualists, as I have already said, but there is a community. There is an Artists’ Union that brings together professional ceramicist sections in almost all the major cities of Lithuania. Joint exhibitions, outings and events are organised. Other groups are formed more independently, or in other institutions, or thanks to online friendships, or fairs. However, the field of Lithuanian ceramics is not very wide, we all know each other.

Aesthetics of a vessel: from thing to art. Photo: Indrė Stulgaitė –Kriukienė

AS: I guess that ceramicists are also united by their common activities, for example by clay firing. As far as I know, you have participated in more than one anagama firing. Perhaps this is also a connecting link, because doing such activities by oneself would be quite difficult, both physically and financially.

MG: Actually yes, these gatherings do happen, although they are rare, but they are special events. In general, symposiums, plein airs and firings require a lot of time and resources. Going to a symposium and then participating in exhibitions gives a lot of inspiration, conversations and idea sharing, where everyone shares their contributions, resources and knowledge.

AS: When I was studying ceramics, I noticed that there is a clear focus on making the object. I mean, the most predominant area of ceramics is functional/applied. However, at ceramics events, such as the recent exhibition ‘Lutum Magnum’,[1] many examples indicated a desire to try new techniques, methods of formation and presentation. How does it seem to you?

MG: It depends, apparently, on which point you look at it from, and what the direction of the person’s interest is. On the contrary, around me, there are more creators of art than producers of things. And probably again, several layers of this discipline intertwine. It seems that a manufacturer of things is a craftsman, and the maker of art is someone who makes sculptures or other irrelevant objects. I would suggest that it could be viewed from a slightly broader perspective, and not putting everyone in compartments they can’t get out of. In the ‘Lutum Magnum’ exhibition, out of almost thirty artists, there were perhaps only six who worked as professional ceramicists, while the others represented other branches of art, so that clay became a material to express their creativity. I presented a video from my exhibition ‘Rock and Wind. Objects in Space’ at ‘Lutum Magnum’, and it was a work about ceramics. It’s partly a work about clay, too, because it’s made with clay tools, but I’m talking about a vessel. This is pottery about pottery at a clay show, and I guess I’m the only one talking about it. Other artists see from completely different viewpoints, be it ready-made ceramic objects or clay as a material for sketching, or creating innovations using the material. The exhibition was one of the most amazing and interesting exhibitions in the last few years, not only in the field of clay, but also in the conceptual field in general.

Exhibition ‘Rock and Wind’. Photo: Viktorija Zaičenko

AS: Pottery seems to be going through a golden age, with an increase in the number of people experimenting, making and selling ceramics, as well as more ceramics studios and teachers. Do you think the market is getting crowded?

MG: Sadly, I think so. Your perceived golden age of ceramics is already degenerating somewhat, and I think the narrow knowledge of the field contributes to this. More and more artists are emerging, especially through the spread of social media, which is only part of the whole wide field of ceramics. It can be said that the illusion is created whereby you have to do it, or try it, or buy it, too, even if you haven’t necessarily thought why you want to. There is nothing wrong with works of ceramics appearing, but you should also be honest with yourself and think whether you are really in a hurry to monetise your work after two lessons with a teacher in the studio. If that happens, it is precisely what changes the market and the perception of ceramic art in general. A lot of people go to pottery studios, but how many are interested? So the question then arises, is this golden age of ceramics sustainable? I would like it if there was a wider understanding, if the field of interest was as broad as possible, if knowledge was expanded, exhibitions visited, and literature read. Then it would be possible to build even stronger communities of ceramic artists and artisans, as well as collectors, buyers and hobbyists, who love ceramics. This is also why the ‘Lutum Magnum’ exhibition was so fascinating, because it encouraged conversation. This variety is fun.

AS: It would be interesting to know about any creative plans you care to share with us.

MG: I recently presented a personal exhibition of work at the Baroti Gallery in Klaipėda, which I would like to show in other cities as well. I also have ideas for several artistic projects. The issue of copyright and fair remuneration in Lithuania is still relevant to me, so there are definitely plans in this field. Of course, in the near future I am concentrating on not being overworked, and having fun while creating. I am collecting a library of books about ceramics in my new studio. I read quite a lot.

My teacher Professor Jakimavičius, I can’t remember the exact context, said that there is a lack of cultural ecology in the field of art. I have returned to this idea in my work in recent years. I wonder how productive I have to be, and ‘bake’ piece after piece. I have tasted some of that tiring overproductivity, and am currently observing both myself and the environment. I am not in a hurry to create something, prepare and present it. Choosing which exhibitions to attend makes the event more like a celebration. I want to focus on the meaning, ask questions and look for my own answers, how my work can be important, where I can present it. Sometimes great ideas that appear in the wrong place and at the wrong time may not convey the message at all, or go unnoticed.

Exhibition ‘Rock and Wind’. Photo: Viktorija Zaičenko

Aesthetics of a vessel: from thing to art. Photo from personal archive

Exhibition, How Long does Creativity Last. Photo: Ingrida Mockutė – Pocienė

[1] The ‘Lutum Magnum’ exhibition took place from 17 June to 11 September 2021 at the Museum of Applied Art and Design in Vilnius. The curator was Rokas Dovydėnas.