For a visitor who comes from packed spaces, bustling streets, and heads buzzing with ideas, Marija Šnipaitė’s exhibitions could convey an unexpected sense of meditational feeling: they are melancholic, silent and minimalistic. The works are graceful and fragile, inviting us to touch and hold them in our hands, whispering different stories that are known only to us. What is behind these objects? Marija Šnipaitė (b. 1988) is an artist and sculptor who has an MA in sculpture from Vilnius’ Academy of Art. She has been a teacher of creative disciplines for several years. In this interview, we talk about Marija’s recent third solo show ‘Somnolence’ at the Artifex gallery, the inspirations in everyday life, and her openness to dialogue.

Agnė Sadauskaitė: The Artifex gallery hosted your personal exhibition ‘Somnolence’ in October, which was spread across three gallery spaces. It invited us to see works that transform life situations into landscapes, and body parts into coloured forms, where every day phenomena disappear from … everyday life. Could you tell us more about the idea behind the exhibition? What are the connections between the pieces?

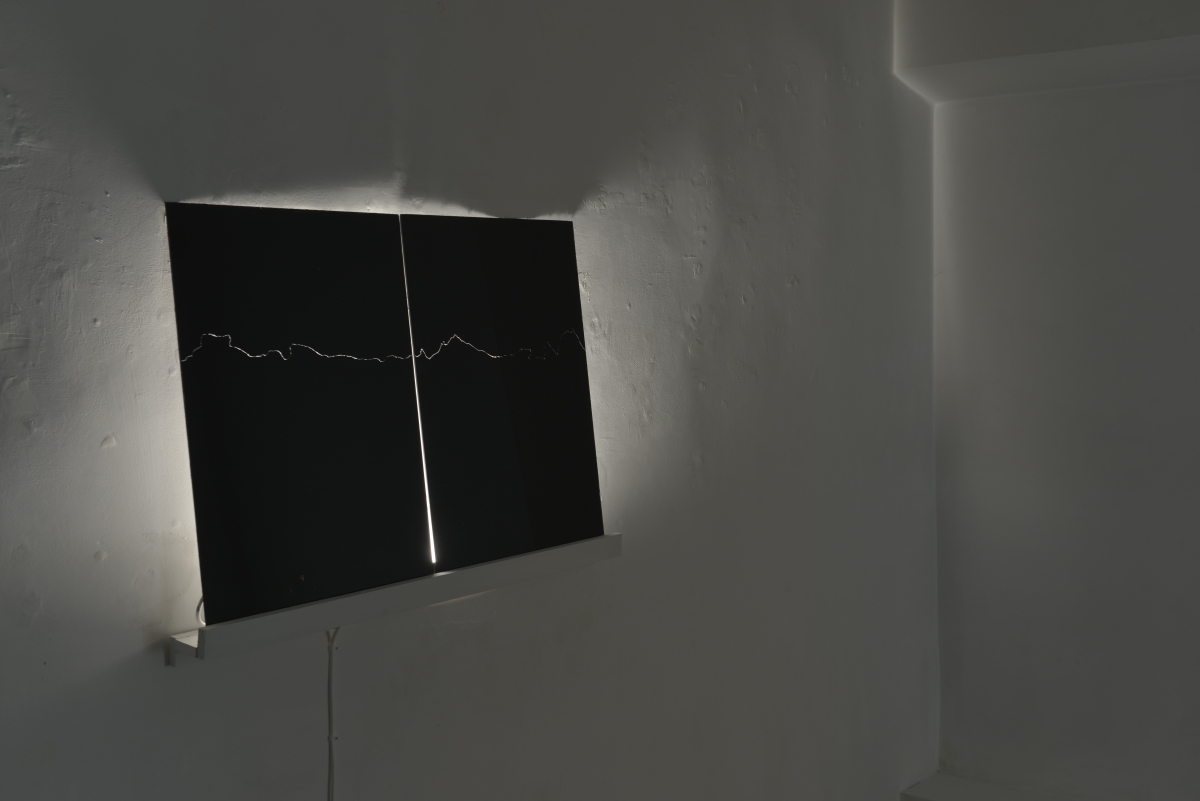

Marija Šnipaitė: I wanted to look at somnolence, not as a transitional sleep phase between closing the eyes and deep sleep, but as a feeling, a very short, episodic measure of time that lasts only a few minutes or seconds. Looking at the structure of the exhibition itself, one space represents connections with the human body, and objects created through the interpretation of the body’s characteristics: flexibility, slickness, colour. Another space resembles landscape. The third space is minimal, as if more distant from the first two. A key element of the exhibition was the creation of atmosphere, a quest to create a melancholic, slow, time-indefinite space. I wanted objects and spaces to have different moods and themes, while merging into one dream, where the connection is palpable, but when trying to bind together the narrative, its ends still do not connect with each other.

AS: Is it similar to the clear image of a dream that can be experienced every night, but as soon as you get up there is only a dim memory left?

MŠ: The parallel between a dream and the current exhibition came up only during this talk, as we speak. It sounds logical: somnolence itself leads to a dream state. Still, neither during the process nor during the opening have I presented the exhibition as a dream. I think about the feeling a few moments after you wake: everything seems to have been very clear, you want to tell it, but you realise that once you start telling it, it disappears. Subconsciously, this impression was exactly what I was trying to achieve in the exhibition.

As for the works themselves, however, I was thinking not about the development of the state of somnolence, but about the margins of this feeling. Just imagine: there are noises in your environment, you also communicate with your senses, you see what is going on outside the window, you can touch things nearby, think something, and there you go: the story of the person nearby, the murmur outside the window becomes dotted, the environment is slowly erased. It is this transitional phase that interests me.

AS: How was the gallery space itself? Was it enough, with regards to space?

MŠ: The Artifex gallery tempted me with the structure of the space. There may have been some hesitation at the beginning about how to place the pieces in the small space, but eventually the environment was very suitable, and allowed for physical closeness to the objects and a dialogue with them. I have noticed that often in a space, I organise my work as a dialogue: objects are put in pairs in the room. A pair, a duo, is a compositional principle that I believe in.

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019

AS: You call your works directed spatial installations, in which sculpture acts as an event. In your work, the motifs of a journey and scenery are important, which, being the background to events, can often become actors themselves. Who or what is the main character in your installations?

MŠ: Character is my recent dilemma. I started to explore the theme of landscape, a journey, while I was studying. In parallel, I began to apply the term ‘directed installations’. I became interested in how the installation resembles scenography, with the props and structure of the materials. The elements of the piece appear to be waiting for action. For years, I relied on the idea that a work emerges from an implied storyline, a narrative, and left the viewer the possibility to imagine a character through associations of objects and a possible storyline. I myself was distanced from what the viewer would see and interpret, retaining my own story. Eventually, I noticed that the storyline and the narrative were becoming less important to me. I became more interested in the idea of what an object, which is enough on its own, would look like. I began to focus on the emotional state, the atmosphere, and I never saw or planned the character at ‘Somnolence’. I was surprised to hear the feedback: ‘Oh, now it is. I haven’t seen a character before, and here it is!’ When I let go of the need to talk about the character, it came into being by itself.

AS: You mentioned before that when you set up an installation, you do not really know if the audience understands the sequence, the relationship between the objects, how you imagined it. In exhibitions, you engage in a dialogue with the viewer, silently describing and connecting the narrative, but what the viewer responds or interprets is unheard for you, as the same on the viewers’ side. Is this conversation enough?

MŠ: I accept this as something natural. A correctly read piece of art sounds very strange. Especially when the works refer to quite abstract categories. And here, much like in normal social situations, it’s easy to maintain a dialogue with some people, while with others only few words will be exchanged. I use the sculptural language of shapes, materials and images, which is primarily close and familiar to me. Therefore, it is likely that, as usual in the conversation, there will be people who will find it interesting, and some who will just shrug their shoulders and go away.

AS: Are scenography and scenery still equivalent to the atmosphere created in your work?

MŠ: They are still important, but the emphasis in my talk about the importance of the narrative is declining. Previously, I planned a sequence of actions as A-B-C-D: here comes A, then B, and so on. Now it all goes a different way: A, then D, from D to B, and remodel A. If previously I had an image of a finished piece at the beginning of a work, I do not see it now, and the process is more about experimentation than realisation. I guess that this shift in my work was driven by the thought of whether I could create an object that was sufficient in itself, as I was always working with directed installations. It could be that no change could be grasped when comparing my recent and older works. But here I’m talking more about shifts in personal relations to what I am doing.

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019

AS: You often use materials that are easily found in the environment, including household items, and even the leaves of a plant, or bicycle tires and tubes. Does the use of natural objects in creative work reflect current trends in ecology and sustainability? How do you choose the materials?

MŠ: Materiality is very important to me: every material has a message to convey. As an additional element, it goes parallel to the shape and motif. The use of secondary raw materials usually comes from the elements and actions observed in daily routine. For example, I had a flaw, forgetting to water the plants, and after that, the ‘ritual’ of collecting dried leaves and putting them somewhere on the shelf. I once noticed the piles of leaves here and there, I gathered them up and took them to the studio. There are many random trinkets here and there, which, like those leaves, I move from one corner to another, break, and add to one thing, or to another. I leave them for a few days and come back again. When you are hooked on some mixture of materials, you can develop it further.

The ecological theme is not emphasised in my creative work. I think it’s easier and more effective to do it in real everyday actions. However, I recently thought that the process of creating works of art could become strange and absurd once created for storage spaces, (maybe) future exhibitions or something else that is not so concrete. I thought it was fun to be not committed to your own art, that you can remake already-created pieces by using materials or elements in other situations. This is how I have been using wax recently. For one job, one of the elements was a sliver of wax, and as it was too thin, when carrying it carelessly, it broke apart. Afterwards, I melted it down and used it for other work. These noble materials give me freedom.

AS: It seems to me that good creativity is born out of happiness or pain, but often inspiration comes from boredom, which could be called routine, the cycle of everyday life in which we all spin. What inspires you?

MŠ: I think this is quite an accurate thought. I have thought that it takes a lot of time to observe, to do nothing, for the works of art to emerge. I don’t know if I have discovered something from which I would have impulsively developed the work. Creation takes place through everyday activities, such as picking leaves off plants, cycling, leaving pieces from previous installations, and coming to a studio space where all these elements are placed. I look around, and come back to them, again and again. After that, all these experiences begin to merge. Then you can take a pencil and a sheet of paper, make a sketch, and develop it. Inspiration for me is more fluid than an impulsive phenomenon.

Installation view. 1 km/h. 2015

AS: What, besides the daily routine, brings creative stimulation?

MŠ: Literature lays the foundations for thinking. The open-ended narrative structure of Witold Gombrowicz’s novel Cosmos laid the foundations for how I began to construct the space for installations. Now I notice that there is enough inspiration not from the whole story, but often a single word is enough. For example, when I was preparing ‘Somnolence’, I did not know exactly what I wanted to try. The word ‘somnolence’ came up, and it became a landmark: you think about the interfaces, you start to notice somnolence in your sleep, watching a passenger on a trolleybus, in a movie … So I created a word that became the whole theme, and started being with it, trying to understand it. Of course, there are all the visual experiences: the creations of others, the images through windows and screens, but that goes without saying.

AS: You participated in the programme ‘Teach first’ (in Lithuanian ‘Renkuosi mokyti’), and have worked as an art and crafts teacher in state and private schools, and currently at the National M.K. Čiurlionis School of the Arts. What motivated you to go into teaching?

MŠ: While studying at the university, I thought it would be interesting to try this area. Observing how the visual arts and other creative disciplines are taught in most schools gave me the desire to contribute to a change in the education system, to communicate with children, and show them that art is not only a question of pretty or ugly, but also to talk about its context and concept, its connection with history, literature and other fields.

For over three years, I have had many different roles as a teacher: from teaching in ordinary schools and running creative workshops for country children, to communicating with children who are being educated in perfect conditions. Each stage, regardless of the duration, gave me very useful, dynamic experience. Now the original ambitions seem distant, but possible. Of course, teaching in an art school is based on slightly different principles, which I am still trying to understand.

I believe this is usual for a teacher, as a dedicated, sharing person. However, at the same time, it is a potentially a quite selfish personality (especially when teaching art): the students’ leaning one way or another goes through your own world-view, thinking, attitudes and values. Therefore, it is important to remain open, not to become conformist. But all this brings out one of the more enjoyable moments of this activity: the success of the students, which happened unexpectedly. You can actually enjoy these successes for half a day like your own … At least for now.

AS: What changes would you like to see in schools?

MŠ: As far as high schools are concerned, I would like more professionals working in them (and here I’m talking about all disciplines). In addition, having a dialogue between different subjects would increase children’s ability to explore phenomena on several levels. Let’s say you can deal with Cold War topics in different disciplines … but it’s inconvenient. There are plans, tables, requests and permissions, sayings such as ‘I don’t get paid for this’, and so on. Changes are happening, but so far only in isolated cases.

AS: Do you think that knowing art in childhood is important for the development of your personality? What would a person gain from participating in a daily dialogue with art, in exhibitions, galleries, and having a good mentor to guide him or her through these spaces?

MŠ: I have noticed from students that there are cases when they bring a picture, saying they can’t create. That picture is simple enough, but what’s depicted, the motif, the plot of how it is presented, you can find something attractive in it. Then you find out that the child’s family is constantly taking him to museums and exhibitions, so you notice that the child sees the world in a different way. Although he often declares that he’s not interested in art, I still think that there’s a growing awareness that it’s possible to discuss things not only verbally, but using different tools. These other ways can be very different, so you really don’t need art every day.

Exhibition view. Retreat. Marija Šnipaitė, exhibition view, (AV17) gallery 2018

AS: Are there any other important aspects besides sculpture, such as painting?

MŠ: When creating installations and atmosphere, I think about how to introduce other disciplines into sculpture, while maintaining the basic principles of it: material, form, space and our relations with it. I would not say I go too deep into other areas. Rather, I impulsively pick up small elements, segments that fit my creative work. For example, drawing plays a very important role in the process itself, so it moves naturally into space. You often think of an object as a line or a blemish in space. With other areas, like pottery or watercolour, I always had a complicated relationship, but here in the ‘Somnolence’ exhibition, there is both.

AS: Does one of these segments seem likely to become a prime form of creativity?

MŠ: It sometimes appears that I have created a replica of things that I have already created in the past. It feels uncomfortable. But then I get out of it. My work is quite consistent, changing only slightly in appearance. It does not involve following trends or studying in-depth the topics I’m developing. Maybe my art looks at feelings, emotions, in an old-fashioned way, which is much harder to convey in sculpture than, say, in painting or drawing. This is one of the big dilemmas, when there is a state or feeling I want to capture, but it takes a long time. Perhaps from that comes consistency, you tame the awkwardness; you discover how to turn those obstacles into advantages. Although I have long thought it would be fun to paint or dive all the way from visual things like texts, I have not taken any real action so far. However, if I see that the visual expression used so far is no longer relevant to me, who knows, I might find the courage to try other areas as well.

AS: You call yourself a creator of directed spatial situations, with landscape and everyday situations as some of the main themes. What are your future plans? Will these themes go on?

MŠ: I’m not planning any radical changes or new exhibitions yet. I’m planning to return to the studio, where I’ll find the rest of the pieces of wax or unfinished parts of previous pieces, and then something will develop and be created again. It was quite an intense phase, and now I’m living in a pleasant feeling of emptiness. After each show, an intense phase, a wish comes to experience that alienation, the need for idleness, calm. I would like that for myself in the near future.

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019

Exhibition view, ‘Somnolence, Artifex gallery. 2019