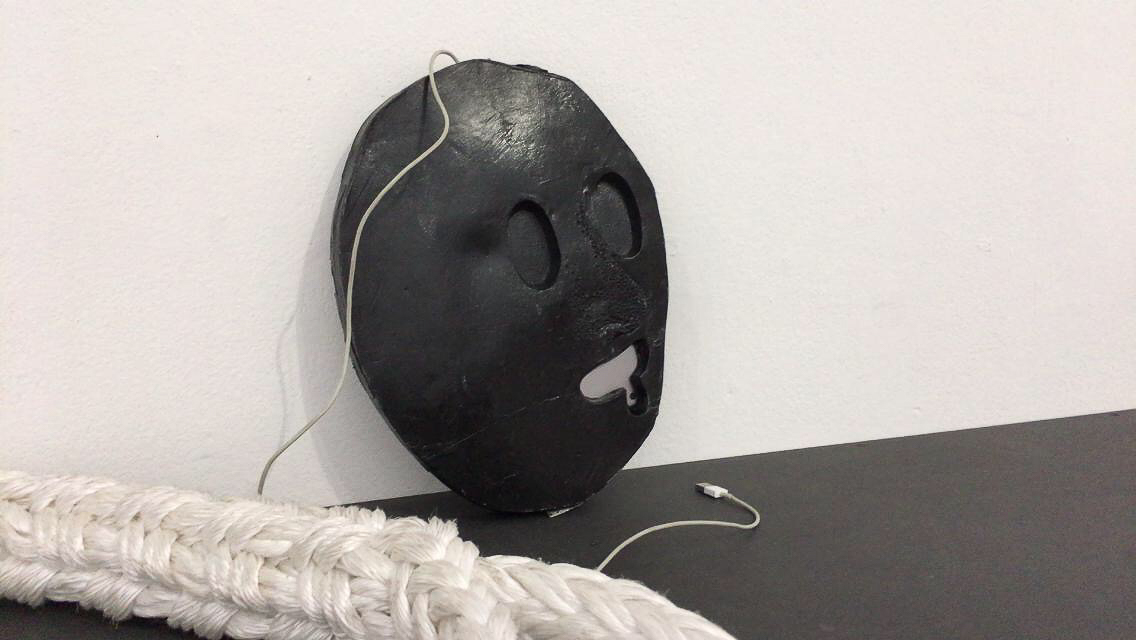

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Borbála Soós is a London based curator, currently undertaking a residency at Rupert, Vilnius. As a former collaborator of Robertas Narkus (she hosted his project , Turbulance 3 – curated by Juste Kostikovaite, at Tenderpixel in London in 2014), she caught up with the artist and took the chance to interview him on the occasion of his new solo exhibition, Träger at CAC, Vilnius.

Borbála Soós: I have only seen very few exhibitions that functioned at least as well if not better on the opening night as on a regular day. Why do you think the installation worked so well during the Private View, with hundreds of visitors?

Robertas Narkus: From the beginning, the project was conceived in a way, especially in its communication, that audiences from a large spectrum could approach it, and as such, it had to have a certain volume. It was a task to have a constant flux of people. I noticed that during the Private View people started to learn from each other how to use the show. They could see that different people are holding iPads or searching for something is particular corners, then they would also try and seek out these details for themselves, and compare experiences and opinions. It feels like the show is ‘sneezing’ a lot of different things…

What were the technical challenges of putting the show together, and making it work technically?

The technology and technical things are present in the exhibition, and of course how they manifest exactly are very dependent on the professionals of their fields who were helping to make them happen. For instance, the machines were developed by Techanarium a Vilnius-based, community-operated maker space, with quite a punk approach. I think it is because of my limited technical understanding that I can feel free to ask crazy questions: this was my task. I am totally a technically illiterate person, but maybe this is why I am attracted to working on problems that are hardly possible to solve.

I am not fetishising technology though. For example, there are two very different approaches to the moving machines in the space. One of them was very complicated and hacked, we spent many many hours of programming it, and it was finally only resolved very last moment. While the other solution was very simple: we tied the wheel with a rope. In the end, both machines are essentially doing the same thing, going in circles. This approach is present in many instances of the exhibition, so it is also about the lightness of doing things easily.

Working with the technology is in the context of what we have been doing with the Institute of Pataphysics. We are interested in the science of imaginary solutions, which we started using as a tool to penetrate technology companies. This is where the augmented reality and virtual reality was coming from, that you see in the show by looking through the iPads or your smart phones. Actually, these technologies are not entirely new. Of course, I hope that in the framework of the exhibition there are a few things that might open new spaces, but essentially scanning and augmented reality have been present for a while and are not new inventions.

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Do you see a hierarchy in between the works? Do you think there is a central piece or key point in the installation for you?

While the installation might look random regarding aesthetic decisions, I definitely wanted to achieve a certain emotional setting and set a tone. I always go for the conflict. On the one hand, there is optimism, but there are also feelings from another spectrum. I like to try and connect two different endings…

It also feels like there is a lot of humour?

The humour is a kind of spice that can emphasise and give contrast to the other aspects of the show. I am really serious about humour.

Träger – the title of your solo exhibition points at the carriers, forklifts in English, that are the machines that we see in the gallery, but perhaps also to a certain extent the unique augmented reality experience. It is a surprisingly straightforward title, usually your tiles are a lot more enigmatic?

Träger is the German translation of the word because in this language it has a richer meaning. I think it all started from the title: it refers to a very specific object, but in the meantime, the definition is also very broad, it can also mean a carrier in a chemical process or a person who is, for example, carrying a secret. There are also some scanned people that appear in the augmented reality, carrying things, like paint etc. Träger and tracker is a nice word play. It also brings in the augmented reality as another aspect, through referencing the physical signs that help carry these.

I quite enjoy that the charging stations, the information desk as well as the sleeves of the iPads and the chargers have become an integral part of the exhibition. Was this part of the original idea, or did this rather grow out of practical decisions?

It was the plan from the beginning. I sometimes like things that are very literal. You get the iPads with the faces, and you can look through their eyes, or actually the mouth. And you can also get the app for your own phone from under the table.

The exhibition also has a website, trager.lt, people can subscribe to it, and this extends the experience beyond the gallery space. The live feed that appears on the iPads is coming from this website, which is a platform that is being built. On the page, you find a log, a conversation between anonymous people who respond to an artificial intelligence chatbot, while the pictures that people have taken with the iPads in the show, they are also all going to the website.

This platform started simultaneously with the show, and we are about to open it up to the public, so they are invited to write a question or answer a question. The idea is that the conversation can be either continued by a person or the machine, and you don’t really know which one it is which, or whom you are talking to. The project is still developing. It just reached a moment when it was opened to the broader public for the Private View, and during the next months, there will be other things that will appear in the city and other cities as well eventually. I want to have a large outlet for the show and spread a lot of content all over.

The display at CAC reminds me of an intricate system in the age of capitalism, working as a factory with automatised machines, perhaps with the product of dog food as seen blown up on the massive wallpapers. Were you trying to construct a semi-familiar system of production?

The exhibition is a lot about efficiency and this is present on all levels. Most of the production budget was spent on labour, while the materials present were mostly recycled. For instance, the ramp was built from recycled materials formerly used on film sets and then thrown away. The whole show is organised as a structure, and of course capitalism is present, the setting is there, but it is also about imagining a labourless world.

Do you believe that in the future automatisation can serve us or save us, free up our time, provide a better life and even a new, better society with new goals?

Well, I am not sure. I am just thinking of myself when I am going to the supermarket (there are only supermarkets in Lithuania, all small shops are being swallowed by these bigger players now). When I pay, I always prefer to go to the machine, the checkout point that is automated, but each time I wonder if this is causing some kind of bigger effect. This is definitely where the world is going.

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

There are many objects and salvaged machines in the gallery that were initially designed to serve and accommodate the human body (minibus seats, forklifts with seats etc), but in fact, they are and reconfigured to function efficiently without people. The show is full of faces and face-like marks, ghost figures in the augmented reality…

There is a sense of disappearance through which I am questioning things. We are at this moment when we can wonder if automation is a key that will solve all our problems.

At the same time you can also feel that it was a lot of human effort to produce everything, so of course, it was very labourful. The figures or ghosts present in the augmented reality are actually the people who were involved in the production and installation.

Do you think we are under too much pressure, and perhaps too accustomed to always chasing unrealisable dreams, desires and successes? Are we trained to always have a new desire in consumerist society?

We are a socially hyperactive society, hence we strive for triggers / ‘trägers’. Nowadays we see a new trend of living minimally, however, this can also be interpreted as a new desire. I think I like to work with the idea of desires to a certain degree.

You used to talk about the importance of deviance, the ‘red herring’, the odd one out that destabilises the meaning of the rest. Which element do you consider the red herring in this project?

I think the red herring is one of the great tools. If you think about film directors, they have their tools when building up a story. In this exhibition, I can’t really point out where this red herring is, however there is definitely a trail that you can follow, some kind of conscious effort to build up a way of navigating the show. Just to name a few strategies, the visitors come to the end of the trail by encountering a net or a wall, or they instinctively walk towards two walls with large wallpapers of dog food, in between which you have an entrance, but actually, this is not leading you to an entrance. If you like, you can think of the whole installation as a red herring. But I think nowadays I am a more interested in practical aspects, that have a lot of functionality, reach and communication. I enjoy efficiency and dealing with real economic numbers, such as the number of visitors.

It feels like you are very interested in ‘could be structures and solutions in society’. You call yourself a ‘manager of circumstances in the economy of coincidences’ and used to describe your practice in relation to pataphysics. Is pataphysics a structure, that helps to evade definition or fixed outcomes, while it also opens up new could be structures, chance encounters and perhaps even solutions to old and new problems?

Pataphysics has a very strong tradition, which means a lot in certain contexts. It is obviously very meaningful, and I have benefited a lot from this tradition, and it still has a very rich and expanding world. In a way, it is a privilege that I got by chance and circumstance access to this knowledge. But I am more interested in subverting it and bringing it somewhere else, and you can’t do that by just neglecting the tradition, and by only looking at it critically on its own without a discourse. Bottom line, I see it as a lifetime hobby.

You are the founder of the Institute of Pataphysics in Vilnius, I also know that at least one of the curators of the exhibition Audrius Pocius is also part of the Institute. How is the Institute doing as a network nowadays?

It has a very solid structure. A few years ago the Institute decided to manifest itself through a visionary artist placement programme, which is run by the Institute of Pataphysics, as a kind of useful-useless institute. The Institute is also very helpful when approaching companies or other power structures with a portfolio that can demonstrate a ‘scientific approach toward creativity’. It also has a few other projects that are following the tradition of pataphysics. Currently, we are in conversation with the College of Pataphysics in Paris, and we are about to publish (or not to publish) a book on cacti linguistics titled Latis Linguistics Of A Scientific Vocabulary.

Presentation by Robertas Narkus, Autarkia ‘kick-off’ event, 2016. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Front view, Autarkia, 2017. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

After living in Amsterdam for three years and finishing your studies at the Sandberg Institute, you moved back to Vilnius last September. At the same time as preparing for this major solo presentation at CAC Vilnius, you also found the energy to set up Autarkia, a new artist-run space, described as an artist day care centre, a club of interests, an office space for putative experiences and imaginary solutions, a bistro of experimental gastronomy, a gallery and project development hotel in Vilnius. As far as I know this is only artist run organisation in Vilnius. How is it going? And is it indeed self-sufficient?

The three years in Amsterdam was an extremely useful and important period; many things changed for me during this time, such as patterns of working. But moving back to Lithuania felt reasonable after three years. Somehow doing things in Lithuania have more importance: it feels like you can effect more, even though sometimes you are operating on a smaller scale, the collaborations are more intense compared to Amsterdam. Although I must say I have a good network of friends and collaborators there too.

Autarkia has a purpose in the cultural field on Vilnius, it feels like it filled a particular vacuum. Setting up the place is rooted in the visionary artist placement programme by the Institute of Pataphysics I was talking about earlier. There were two projects within this. One of them was dealing with a virtual reality company that later on developed into the part of the show at the CAC that we see as augmented reality. And we were also interested in expanding to another direction: we worked with genetic engineers to help develop a technique and create a glowing plant as an artwork. We created a hydroponic system that was called Autarkia, because it was supposed to be a self-sustainable system that can house the glowing plants. It was a big undertaking that involved many people, engineers, philosophers, writers, scientists etc. Last autumn, that also coincided with us moving back to Vilnius, and with starting to prepare for this solo show at CAC, I was looking for a space to present the plant project. We found this canteen that just closed down, and decided that it would be the perfect place, and it all started to from there. After operating for about six months now, it feels like Autarkia is fulfilling its promises, for example, we managed to give place to a large variety of exciting projects that couldn’t fit anywhere else. We have already ‘inhaled’ a lot of things, meaning that we are gathering more and more people who regularly visit Autarkia. There is quite a lot of support and enthusiasm from various audiences, from different segments of society. I don’t know how long it will go, put the project started with the perspective that it will run at least for ten years, so it is not a short runner.

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Robertas Narkus, ‘Träger’, exhibition view, CAC, Vilnius, 2017

Photography: Robertas Narkus