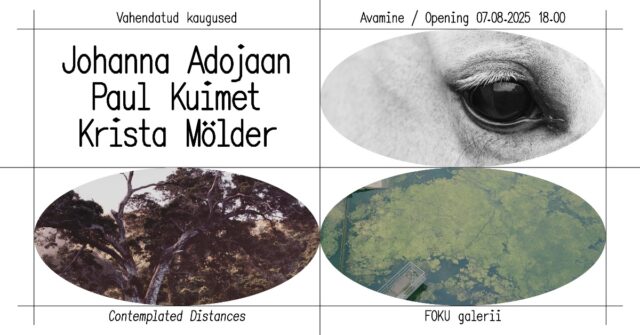

Past the ellipsis and ampersand, our journey across the question of this biennial fittingly ends with the question mark, whose roots furrow deep into the soil of our collective subconscious, feeding on the hesitations, aversions, complexes and misunderstandings.

Full transparency, it’s my favourite part. These performances pose concrete questions for the audience to grapple with, offering us puzzles that have as many solutions as there are sets of eyes gazing upon the pieces.

Dovydas Laurinaitis

-lalia / Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė

A huge crowd of people is gradually seeping into the foyer of the National Drama Theatre, at the centre of which is what looks like an empty pool with a golden statue inside. An expectant camera has been set up and no one dares to go in the middle.

The location is almost too charged in a way.

Why can’t we come closer? Who dictated this distance? Upon entering, I was only told to switch off my phone. I heard they will be playing with the hierarchy of the space by having the live action taking place in the foyer and a live-streamed version shown in one of the performance spaces. I bump into Dorota before the performance begins.

Remember to take the lift to the fifth floor.

I wonder what that’s about…

A hush sweeps across as a performer, seemingly possessed, enters the empty pool barefoot, wearing an all-green suit. She begins lip-syncing to a text about soil. I can’t say much of the text registers so instead, I let it wash over me, entranced by the sight of the grotesque physicality with which she’s delivering this speech.

In the end, the text was not important.

It’s a strong choice, generous offering and clear illustration of the way an experienced performer understands what it means to create an energetic space for the audience to inhabit. Despite our numbers, she easily manages to hold us in the palm of her hand.

Behind her, I begin to see a few people slipping away towards the staircase. Joining them, I take the lift to the fifth floor with two people, who I think are on a date. She’s asking him about what kind of notifications he gets on his phone.

As the doors of the lift open, I hesitate slightly at the sight of the black, windowless hallway with dim white lights guiding the way. Huge contrast from the brightness and airiness of the foyer. I rub my hand against the wall that looks like sound insulation, feeling rough stucco instead.

The second space has been set up as a movie theatre and on the screen is a live broadcast from the camera downstairs. Obviously, the work is exploring mediatisation, and the separations are clear and concise: between the action and the screen; the text and the recording; the recording and the lips.

It looks better on film. You can tell her movements know where the camera angles are.

The framing of the film makes the spectators downstairs into co-actors. I watch a cross-legged blonde woman speaking to her friend, unaware of the possessed performer inching her way closer, until an accidental collision of shoulder to shoe startles her, leaving an uncomfortable expression on her face.

The performer’s eyes look glazed over—what is she seeing? Perhaps hearing my thoughts, she picks up the camera and points it at her eyes. Looks like she is wearing coloured lenses. So she’s making ‘herself’ purposefully unavailable, reaffirming her position as a creature of mediatisation, a vessel for the voice of another. I wish there had been more of an entrance into this state of possession. How did it happen to her? How does it happen to others?

While highlighting this question of distances, the performance doesn’t provide any answers, comments or conclusions to these ideas. Did the artists decide on the relationship between the action and the film, or is it up to us? Is that a cop-out? What does the knowledge of the event downstairs do to our experience of the work?

I was expecting more from Dorota and Eglė.

I take the lift back down, now very conscious of the way this physical movement from privileged subject upstairs to self-aware object downstairs suspends me between two extremes and leaves me to figure it out for myself. It reminds me of being lost in a supermarket as a child.

Of course, there is the question of awareness and afterwards, I found out many people didn’t even know there was a second space upstairs.

Amazing… I’ll see the documentation, I guess.

Not long after returning to the foyer, I notice the text has completely disappeared into the atmosphere. Once it finishes, the performer seemingly sobers up, slightly confused at where she’s ended up, and exits.

Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Damascus, Copenhagen, Fetish Shop / Adam Christensen

Behind MO Museum, under a grey sky of falling rain, people gather on the descending levels of a three-sided pit. At the centre, a spiral indent in the concrete has been made into a stream, partially lined at its running edges by swathes of pink roses.

This location is very well chosen, it allows everyone to see what’s happening.

Adam walks in casually, wearing an extravagant, pink mesh nightgown with frilly green trimmings, barefoot with only underwear underneath. His curly, almost-black hair always partially obscures his face. He talks to the audience surrounding him about the performance he is about to do (distracting us from the fact it’s started already?).

He begins playing a voice recording of himself talking about having to do the performance he’s currently doing (meta) and precedes behind the people standing on the open side of the pit to draw something on the pavement. Despite the space offering many vantage points I try to carefully move through, I can only somewhat guess it’s a face; I resign to not seeing it fully and make a note to check it out at the end.

What follows is a medley of cigarettes, groans, minor accordion chords, readings and more voice recordings. In moving with and through these elements, his casual treatment of the space feels like an invitation to relax, respond and get lost in thought.

Maybe my reproach for the performances is that so many of them are really text-based, linking the performer to the writer, which I find to be a bit annoying. But in this, the text is truly independent while still meshing together with the performance.

When playing the accordion, his body collapses into it, as if trying to fuse. In between two alternating chords, his piercing, melodic groans leave a trail of goosebumps on my wet skin. I cannot make out what he’s saying, but it’s almost as if he’s asking for help. His singing reminds me a bit of Nina Simone, filled with raw and unmeasured emotion.

The mournful atmosphere created by this melody makes me feel like I’m at a cemetery burying someone on a rainy day… Who though?

When reading from bunched-up yellow pages, his accent punctuates the text in an endearingly sarcastic way. His speech is blunt yet animated, dramatic yet matter-of-fact. Someone is emerging from the stories—‘Emily’.

Second mother… mother’s lover… you really did love roses, pink ones… I miss you, especially today…

Another song and then he goes to read again, this time from the laptop of the sound guy’s desk, in one of the pit’s corners. This should’ve been printed and read from the same yellow pages. You can play with spontaneity but with thematic consistency; the specific choices of material carefully construct a world this gesture undermines.

Sometimes artists are so disorganised, doing whatever they want in the moment.

Last song. He suddenly finishes, grabs a bunch of the pink flowers and leaves, disappearing into the distance as another voice recording plays. I’m touched by how much he can reveal while always keeping something for himself.

On my way out, I see a bunch of pink roses left by a charcoal portrait of a woman on the pavement.

Damascus, Copenhagen, Fetish Shop. Adam Christensen. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Damascus, Copenhagen, Fetish Shop. Adam Christensen. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Damascus, Copenhagen, Fetish Shop. Adam Christensen. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

The Cat Practice / Pontus Pettersson

By the fountain of the National Opera and Ballet Theatre, seven performers, comfortably dressed in tracksuits and loose clothing, begin in a huddle with a collective sung ‘aah’ before breaking apart and dispersing in all directions across the various steps, edges and platforms.

The audience, scattered across this architecture, uses their bodies to create a negative space in the ‘centre’ meant to resemble a stage, even though it’s clear that’s not what the performers want or need. I wonder if it’s out of habit or due to a lack of guidance. How much instruction is enough and how much, too much?

Embodying the behaviour and personality of cats (but not the literal physicality), the performers begin this exercise in ‘becoming’.

Sometimes they are doing cat poses and cat attitude, and other times, their movement is very choreographic.

They are getting distracted and spooked, running and hiding, playing with strangers and rubbing against the stone and concrete to leave their scent.

One of the performers comes and kneels next to me. I pat her head. Small response. I wait, then try scratching behind the neck and ears. After a few seconds, she moves on. I think she didn’t like that so much.

Some cats are friendlier, allowing people to stroke them for a while. Is this ‘becoming’ a facilitator for intimacy? I suddenly remember that anti-piracy ad from the 2000s (‘you wouldn’t steal a car…’). You wouldn’t stroke a human, but they’re a cat, so it’s acceptable (?).

A participatory performance like this relies completely on the audience, without whose input, it becomes one-note. I’m aware of how quiet it is. The performers are working hard—finding newness through repetition and exploring the limits of motifs. The audience, not so much.

When I read the description, I thought ‘No, I’m not going’.

The performative contradiction of using cats to facilitate intimacy is that cats are not known for being needy, usually waiting for others to approach them first, which in this context, requires an act of bravery. The kind of generous invitation and encouragement needed to counterbalance the self-consciousness of the audience doesn’t lend itself to the natural qualities of cats, meaning there’s only so much the performers can do without the action becoming cartoonish.

I’m happy it’s about engaging the body for once, no text. I think I like it, but I don’t find it brilliant.

There’s still this negative space of an assumed stage in the middle. I walk onto it out of annoyance to break it. I feel people watching me. But slowly, slowly, slowly the crowd becomes a bit more entangled. I hear a few brave tsk-tsk-tsk’s.

Maybe it needs to last a little longer…

In time though, the negative space reforms. I’m not going to do it. I did it once already. Let’s see if someone else will… before I can finish the thought, I have walked into the middle again. However, this time, I notice a grey-haired woman, smoking and leaning on an umbrella, follow me.

She takes her sandals off, offering them for the cats to play with, her bare feet on the wet concrete. The cat who didn’t like the scratch before tries to catch my moving foot (she’s very good at it) and for a moment, we’re almost dancing. I spend some time offering my umbrella for her to play with. Eventually, she gets bored and moves on.

The grey-haired woman (still smoking; is it the same cigarette?) and I exchange a knowing look and smile. We’ve understood this lock needs our key but we’re waiting for others to fully realise.

By the end, the audience has begun to defrost, with people trying increasingly provocative ways to engage the cats, like throwing objects to them. It does make me wonder how the participation of a more courageous audience would develop and expand the work. On the other hand, maybe that’s why we need this performance here.

The audience are scaredy cats!

The Cat Practice. Pontus Pettersson. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

The Cat Practice. Pontus Pettersson. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

The Cat Practice. Pontus Pettersson. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

False Falling / Keithy Kuuspu

Inside one of the cleared-out halls of the former sewing factory, Lelija, various wooden and metal structures create a rich yet bare scenography the audience envelops from all sides. There is a pool table, manual cement spinner, wheelbarrow, monkey bars, tyres, scaffolding… A sense of crude materials awaiting refinement. Agonisingly sterile lights invade the eyes trying to take in this warped playground.

The light is really strong, it’s painful.

Six performers gradually enter, all wearing black dresses with their hair in ponytails. Performative neutrality strikes again. They gaze upon us with obscure intent. After claiming ‘their’ spot in the space, they become preoccupied with a zone, movement or object in circular and seemingly meaningless gestures, as if solving an unanswerable question.

A performer takes her position at the square pool table in front of me, which I assume has been contactmiked by the wires running underneath it. Whispers, clangs, feet on wood, phone notifications, echoes, shuffling.

She picks up the pool stick and places a white ball in front of a triangle of nine others. Every movement is slow, considered, cautious. When she hits the ball, it flies off the table, triggering flashes of lightning and claps of thunder that shake the tense and quiet space.

This action repeats throughout, each time ‘resetting’ their established mode of interrelation, changing the performers’ position or pattern in the system. A series of ruptures.

As the performance goes on, I notice more and more people leaving. This work does require tremendous patience from an audience. It’s enigmatic, subtle, opaque. Nowhere to hide in the round though so no such thing as a quiet exit. Maybe a bit of a competitive atmosphere is emerging; who’s going to last? Who will give up next?

We wanted to leave but kept saying ’10 more minutes’, ‘5 more minutes’…

This work could appear pretentious in its inaccessibility, but I just see it as not easily digestible. It puts you to work to get something out of it, requiring endurance from both the performers and the audience. It’s a good way to test your limits with durational performance. This is definitely one of the more hardcore offerings.

Still watching these creatures playing with their inexplicable systems and structures, not understanding quite how they work or what they’re getting out of it, I begin feeling like an alien who stumbled across a documentary on humans while browsing through some interplanetary streaming service.

The more you watch, the more you understand.

No matter how much they try to rebel against or break the systems they’re within, the systems just reform in some mutated way and they have no choice but to participate. Sound familiar?

Even though I understand they’re playing with anticipation and momentum, my patience is also being tested. How to channel this perspective and feeling they’re offering us into interactions with our hierarchies and systems? Aren’t we already tired and aware of the meaningless actions that preoccupy our modern existence? What should we do with this information?

There is no end. I stop fighting and accept my new reality. It’s very hypnotising if you allow yourself to get lost in it. Less than half of the original audience remains.

I realise that without me noticing, everything in the scenography is as it was in the beginning—the balls on the table are once again in a triangle, the scaffolding rebuilt, the wheelbarrow full. The performer goes to hit the ball. She goes to… but doesn’t.

Everyone comes together to bow.

The woman in front of me releases an audible sigh of relief.

These people are like heroes, I don’t know how they do it.

False Falling. Keithy Kuuspu. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

False Falling. Keithy Kuuspu. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

False Falling. Keithy Kuuspu. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

…&?

In trying to reach some conclusions about the biennial, I keep running into a wall. Even after some weeks, my experience of the separate performances hasn’t quite crystallised into a coherent whole. The theme of the first edition was the city, which upon reflection doesn’t feel comprehensive enough as arguably any work in public space will be about the dynamics of the city, in however minute of a way.

The programmed performances explored capitalism, gender, climate change, rest, interdependence, mediatisation, digitality, intimacy, history… While the city is a stage for these things to dance upon, is it enough to simply point out the stage exists?

Performance art can intervene in public space and life, bringing awareness to the performances already happening around us, exposing their fragility and at times non-sensical nature. I wish the biennial had been bolder in subverting and examining the contexts it occupied.

Many of the works were indoors, physically disconnected from wider public life. In these spaces, I often felt part of a theatre audience, looking at something dangling in the distance. As my mentor Season Butler once said, the central conceit of performance is ‘I can look at you and you can look at me’. So by establishing these distances and encouraging a very well-behaved, static audience, the performance becomes a spectacle, something to be enjoyed but forgotten.

To me, there should always be something confrontational about a performance; not violently so, more like meeting a stranger’s eyes through a café window. The friction between thresholds.

It’s difficult to predict whether the foundations the biennial built lend themselves to further development. When we all disperse, entertained but not profoundly impacted, will we emphatically call for the next one?

I, for one, really hope so. Even though the two weeks were a whirlwind, the collective excitement and curiosity showed there is a place for this biennial in the landscape of Vilnius.

As for what will remain, only time will tell.

It was a grandiose ambition.