A conversation with the artist Kipras Dubauskas about his artistic research on islands in the River Neris, and the well-received corresponding exhibition ‘36 Chambers’ at the POST gallery in Kaunas in the autumn of 2019. However, there were no extensive reviews of the exhibition, so we decided to focus most of our conversation on it.

Aušra Trakšelytė: The project-artistic research ‘36 Chambers’, which was presented in an exhibition at the POST gallery in Kaunas in 2019 from 24 October to 10 November, was inspired by Count Konstantinas Tiškevičius’ 1857 expedition, afterwards described in his book ‘The Neris and its Banks’. You said that your expedition, which took place in the spring of 2019, started in exactly the same place, but you chose the islands, not the river, as the main object of your research. What were your motives for choosing them instead?

Kipras Dubauskas: I’d like to be clear about the starting point of the expedition. Tiškevičius started his journey at the source of the Neris in Belarus; while I began at the place in Vilnius where he stopped for a few days’ rest. In the 19th century, that place was called ‘the new pier’. Currently, the only remaining sign of it is a cliff on the left bank of the river.

Regarding the artistic research itself, during my studies, the city and its structures, the street culture, and the cultural layers of the underground, were the main point of my creative work. Later, when I went to live abroad, I became interested in psychogeography, in observing modern, urbanised cities (this couldn’t be said about Vilnius at the time), and the application of artistic strategies in non-institutional environments. On my return, I noticed the speed at which Vilnius was evolving. The city’s periphery and its unused empty spaces became the playground for our artistic practice. In 2013, my colleagues and I initiated the annual MINEO festival, during which we’d organise walks around southeast Vilnius. The alternative routes we traced would often cross private land, and hence the information we’d gather over time turned into an ‘archive of experiences’.

The tours would finish in Žemieji Paneriai, at a secret place near a bend in the Neris. That was the end of the trip. We built a small house there, and the place itself existed both as a creative studio and as a refuge. In order to transport the materials to renovate the house, we built rafts, which eventually became building materials themselves. The place was alive for six years, until it was completely destroyed last summer. That was a sign and an impulse to start searching for a new and less exposed location. And that’s how I discovered the islands.

To me, the islands as a topic for my new artistic research are a sort of ‘no man’s land’, because their territorial status is still undefined. Moreover, they are hard to reach. The river itself protects them from intruders. Some are large and well established, while others are still forming. Some of them are shrinking, some are already underwater, while others, conversely, are expanding.

I felt instinctively that this new direction would elaborate the problematics of my previous artistic investigation. So I carried out the river journey, a 170-kilometre trip on the water from Vilnius to Kaunas, during which I formed a chart of 50 islands. Later, I noticed an interesting fact: the first and last islands had a cultural context. The first one attracted public attention when the artist Saulius Paukštys tried to name it after John Lennon (the Žvėrynas district turned down this idea). The last point, the ‘Island of a Sacred Deed’ in Kaunas, saw a series of artistic acts initiated by Audrys Karalius. So it could be said that the islands only interest artists or scientists, while the citizens and municipalities do not recognise their potential.

The phenomenon of the expedition as a journey or trip that goes back to 18th and 19th-century Romanticism, and also to colonialism, is indeed interesting. I think your project is also somewhat romanticised, but at the same time, there’s a rudimentary degree of colonialisation. In other words, the islands, the ‘no man’s lands’, are admired, but at the same time sought to be utilised. A human stepping into a (new) territory impacts on its development. Surely the interests, methods and goals differ: just like the means of ‘self-perpetuation’. Could you comment on the relationship between humans and their environment, on the biological investigation and research of a particular place? Since, as you have just noted, the relationship between a human and a city, or the identity of a human in a city, the apocalyptic cityscapes, critical discourse on protesting and social identity were previously more prominent topics in your creative practice. But the artistic research project ‘36 Chambers’ focused on an aural and sensory landscape, on the rhythm of movement in a natural environment.

I’ve tried to distance myself from any possible links with Romanticism, with the image of a hermit or an apostate. What interests me is the (geo)political context. A new kind of feudalism prevails in Lithuania today: from the transformations of public spaces, decided upon between certain politicians and construction companies, to the politics of Lithuanian agriculture, by which small-scale farmers are gradually being pushed out, and where excessive growth is currently being encouraged. I want to react to this, so I suppose the ‘taking over’ of the islands is a direct form of protest. These islands will become a platform for various different artistic campaigns in the near future.

What’s more, as an artist, I’m interested in food culture, in what we eat, what grows on its own, and what we cultivate here in Lithuania. I’m fascinated by the wild natural flora, the fruit trees, fruit bushes and root vegetables. The biological diversity I discovered on the islands was great. Some of the islands are in the city, so I am also interested in the use of wild plants in urban environments.

By consciously distancing myself from the city and approaching nature, I ask myself what can I discover as an artist, and then convey to the viewer by employing permaculture, guerrilla gardening principles?

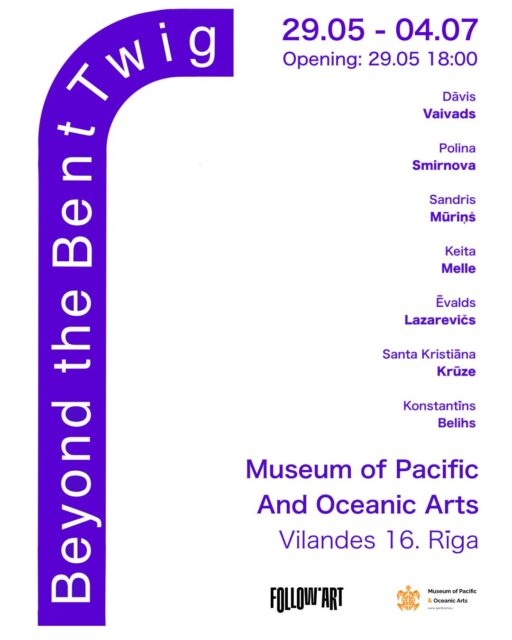

A photographic slide developed with water from the River Neris. Photograph by Simon Marie Sarah.

Both your research and the exhibition are full of references, metaphors and dotted lines … What are the main elements, the ‘structure’, of the exhibition? There were also some works by a couple of guest artists. On the basis of what criteria did you choose them?

The exhibition in Kaunas was an inaugural part of this long-term project. It should be noted that it was the first personal exhibition to which I brought very different elements, although they were characteristic of my creative practice. As you walked into the gallery, the first work you noticed was an advertising light box showing documentation of a performance that had taken place at Vilnius International Airport. In it you could see a man with a skier’s mask holding a piece of paper saying ‘PLATTING FOG’. You often see people with these pieces of paper with names written on them. In this case, the ‘name/message’ signified the impossibility of resistance or the complexity of the situation at that time. The skier’s mask was a direct link to EZLN, the armed Mexican farmers’ movement, which was one of the main examples of resistance in my project.

It was rather complicated to actually carry out this performance, since photography is forbidden at the airport. It’s a high-security zone, where masks aren’t allowed either, because of the risk of terrorism. In order to really show where we were, we had to pass through the baggage area, which was technically a breach of security … The documentation was done by the British photographer Nathan Taylor Marriot. So the masked person visible in the light box greeted every exhibition viewer.

An instrumental version of WU TANG CLAN’s debut album ‘36 Chambers’ could be heard as the audience moved on to the second hall, where there was a reading room. It functioned as a source of information, where you could learn about the contexts that tied together the whole exhibition. It was comprised of a book about Tiškevičius’ expedition (the versions published in 1993 and 2013), books by the archaeologist Vykintas Vaitkevičius commemorating the 150th anniversary of the expedition, the books by Joseph Beuys ‘Coyote’ and ‘Energy Plan For The Western Man’, literature on the Zapatista uprising, the book by Vladas Lašas ’10 Days Of Fasting’ (published in 1923 in Kaunas), maps of underground Vilnius, and literature on water tourism. Among the other books was ’36 Chambers. A Neris Notebook/Prelude’, a small print-run, created together with the Dutch artist Simon Marie Sarah, in which we described our adventures on the journey on the river Neris.

Then viewers would reach the ‘dark’ hall of the exhibition, where the guest artists were exhibited. The criteria according to which I chose them were related to the river. One of the works was a silent film by Milda Laužikaitė: the artist herself sails on a boat on the Neris, playing the trombone in order to wake up residents of Vilnius. Another guest artist who influenced or encouraged the project was Dominyk Bednarek, a boat builder, who contributed an anchor to my trip. I saw the anchor in his studio in Berlin; it had been turned into a candelabrum. So the anchor was exhibited, and the candles were made of pure beeswax. Beeswax, wood, hemp and linen were once Lithuania’s main export goods. These disappearing, or now practically non-existent, cultures are also mentioned in Tiškevičius’ book. I had not previously known some of the people I chose, but I thought their pieces would add to the exhibition and broaden it. For instance, the piece by the Norwegian artist Kristoffer Myskja ‘Smoking machine V.2’ was a mini-cigarette-destroying machine, which lit and smoked them one after another, until they completely ran out. To me, this piece is interesting, in terms of how it reveals shifting opinions, when you fill the machine with smuggled cigarettes instead of normal ones. I procured the former at a market in Kaunas (we used them for the exhibition). It’s no secret that one of the ways they are smuggled into Lithuania is ‘by water’.

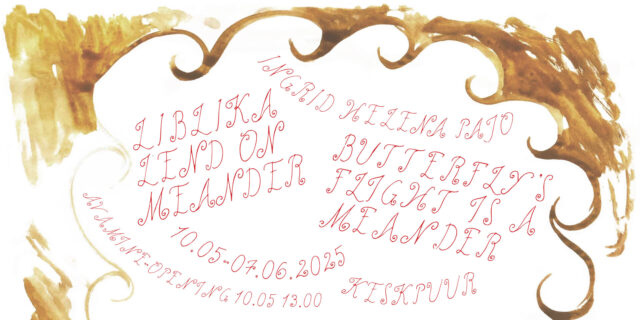

Ryna cave. Photograph by Petras Olšauskas.

The ‘cave’ or ‘intermediary’ space between two exhibition halls hosted two short 16mm films. One of them depicted the destruction of smuggled cigarettes. After some long three-way negotiations, and filling in documents between the Customs Criminal Service and the company carrying out the liquidation, we finally received a permit to film on their premises. During the filming, I acquired a special substrate, which was made from the strained remains of destroyed tobacco and soil. If tobacco isn’t burnt, it doesn’t emit anything harmful. Later, I transferred half a ton of this substance to one of the islands. In the future, I’m planning to investigate this compost material further, and see how it influences plant growth.

Digging the substrate. Photograph by Eitvydas Doškus.

The other short film was an interpretation of Joseph Beuys’s performance ‘I Like America and America Likes Me’ (1974). It shows someone in a mask who reaches a river via an underground drain, and then sails through it on a raft. At Čiobiškis, another raft full of medics reaches him. They carry the protagonist to an ambulance, and then to Ryna cave, where they light a beeswax candle, and where a providential occurrence happens. Then the medics return to the cave, and carry the main character, now unmasked, back to the river bank where the raft is left.

The gallery cave, formed from carpeting material, then led to the ‘bright’ space (the main hall), where I exhibited my sculptural object-raft, which had actually been used for the expedition to Kaunas. We hung a screen on the raft, and showed a series of slides which had been photographed with an old Vilija camera (the Vilija is another name for the River Neris). I developed these slides with Neris water taken from a place near a sewage outlet in Vilnius. The colours of my images didn’t match the reality; they resembled psychedelic tones, thanks to the contamination of the river.

A photographic slide developed with water from the River Neris. Photograph by Simon Marie Sarah.

In this part of the exhibition, the map that Count Tiškevičius made during his expedition was exhibited on the wall. Initially, plan was to exhibit the handmade original; but Vilnius University Library’s Rare Books Department didn’t have enough space to restore an object of such dimensions. Fortunately, I managed to get a high resolution life-size copy. Interestingly enough, the count’s map was drawn during the actual expedition, since artists were involved in the process. I used this kind of map-making technique for my project as well.

I set up my audio piece in a room behind a wall: a reversed recording of the ‘mythological’ Šilėnai spring. It flows in the opposite direction to most others, that is, from west to east. The audio recording filled the space with cosmic sounds.

The last piece in the exhibition was a double slide projection. In one of them, you could see a couple on a boat, waving to the viewer. They were the only other people we met on the whole expedition using water as a means of transport. Another picture showed a recognisable character from the film, posing near a huge hemp bush on one of the Neris islands.

I wanted the exhibition to encompass all the spaces, not only those devoted to the exhibition, but also the lobby, the balcony and the ‘invisible’ spaces. I consciously sought to replicate the movement of a river in this exhibition.

Let’s return to the ‘intermediary’ part of the exhibition, the passage from a ‘dark’ to a ‘light’ space, which resembled a cave, and so became a link with Ryna cave at Čiobiškis. That was the mid-point of the expedition, where you carried out your (re)interpretation of Beuys’ performance. The artist and political activist Joseph Beuys used a lot of symbols and folklore motifs, and, I think, wasn’t an accidental choice. By the way, if I’m not mistaken, the video ‘Suspension of Disbelief’ (2013) is a link to another performance by the same artist (How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 1965). What is the relationship between you (or your creative practice) and Beuys?

By the way, Beuys participated in processes establishing Germany’s Green Party! The cave as an intermediary space was indicative of the real treasures of nature: there are only two types of cave like that in Lithuania, and both are close to the River Neris. Ryna cave was chosen geographically as the mid-point, and metaphorically as passing from one existential state to another. The artistic act here was done to ‘recharge’, to renew processes at the cellular level of our bodies, and to recover strength before the second stage of the journey. From this point onwards, I proceeded on my own, without the Dutch artist Simon Marie Sarah.

The performance at Ryna cave was directly related to the one by Beuys. For example, as he was doing his performance, the artist peed on a copy of the Wall Street Journal, while I used Ūkininko patarėjas (The Farmer’s Adviser), which is published by Agrokoncernas. And the material for my costume was made of 100% ecological hemp fibre, while Beuys used felt … His personality interests me, as it was created according to certain mythical principles. And you noticed correctly: for the ‘Suspension of Disbelief’ video, there was a hare prop, casted from aluminum I found in Ghent, which was also a reference to Beuys’ work. At some point, the artist planted thousands of oak trees, so he is an example of how an artistic practice can formulate tangible responses that affect the next generations. These topics have recently attracted a lot of attention. In my opinion, Beuys’ creative legacy conveys accurately today’s tidings. I personally planted an oak in Vingis Park in Vilnius.

Rynos urvas. Kipro Dubausko nuotrauka

Kipras Dubauskas (b. 1988, Vilnius) graduated from the Department of Sculpture at Vilnius Academy of Art in 2010, and gained his MA in installation at KASK (Belgium, 2013). His creative work has been presented in the group exhibitions ‘Waiting for Another Coming’ (2018, Warsaw), ‘Some Pieces from a Cracked Sidewalk (through an intent gaze)’ (2017, Gdansk, Poland), at the 12th Baltic Triennial (2015), and ‘Words aren’t the Thing’ (2015) at CAC in Vilnius. Dubauskas is the founder of the analogue cinema laboratory collective Spongé.