Collision: an accidental impact between two bodies in motion. But also, in molecular physics, any phenomenon of interaction that leads to an exchange of energy between the interacting particles. A collision is a clash, but also an encounter: an event that activates energy, an occurrence, whether random or controlled, that can bring about a new order through dynamic motion. What happens, then, when it is art and science that “collide”? Confined to different fields only superficially, these two bodies have actually had many a happy occasion for collision over the centuries, perhaps even millennia. Contemporary artistic production now consciously ponders the forces unleashed by these clash-encounters, sometimes even voluntarily seeking out the impact that can ignite the fuse. After all, scientists and artists, despite seeming very distant, all begin with a vision: while the former will try anything to provide an answer to their question, the latter works on the question itself, leaving space for multiple and never conclusive answers. The artist feeds off the knowledge and methods of the scientist, at times distorting them. The scientist makes use of the artist’s imaginative capacity to chart unexpected pathways which may not always be feasible, but are necessary gateways for the broadening of the field.

Under this premise, Collisions seeks to create a platform for dialogue, asking three artists, Marta Frėjutė, Ona Juciūtė, and Simona Žemaitytė, to interact with the vast network of science museums in Naples, which have fundamental historical value in addition to their scientific significance. Following an exploration of the museums belonging to the Museum Centre of Natural and Physical Sciences at the Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (Museum of Anthropology, Museum of Physics, Royal Mineralogical Museum, Museum of Palaeontology, Museum of Zoology), the Anatomical Museum of the MUSA – University Museum of Sciences and Art at the Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, and the Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte, the artists then created original works that address topics arising from the research phase. One is the relationship between the invisibility of physical phenomena and the creation of objects to represent these phenomena, featuring a refined aesthetic and careful artisanship. This is true of several objects in the royal collection of the Museum of Physics that specialised craftsmen were called on to manufacture. They show the ability in Neapolitan craftsmanship to combine aesthetics and functionality, thanks to a profound knowledge of materials. Take, for example, the electroscope conceived by the physicist Macedonio Melloni and created by the Neapolitan builder Saverio Gargiulo in 1855, an artistically and scientifically remarkable work. Or the hydrostatic scale designed and built with different metals by Bonaventura Bandieri for the Bourbon Physics Laboratory, long considered the most accurate scale of those manufactured in Naples, a perfect synthesis of art and science. As the Laboratory’s director, Giacomo Maria Paci, taking it in hand in 1845, noted: “Bandieri figured out how to unite what art and science suggested to him to combine elegance with perfection and thus make his work worthy of this Royal Laboratory.”

This emphasis on the materiality of the object and its intrinsic value expanded into a reflection on the very concept of museum legacy; many of the instruments in the Museum of Physics, although perfectly functional, have been surpassed by technological devices over time. They thus become clues in a history that retraces the steps of scientific evolution, taking on new status beyond their initial one of pure functionality.

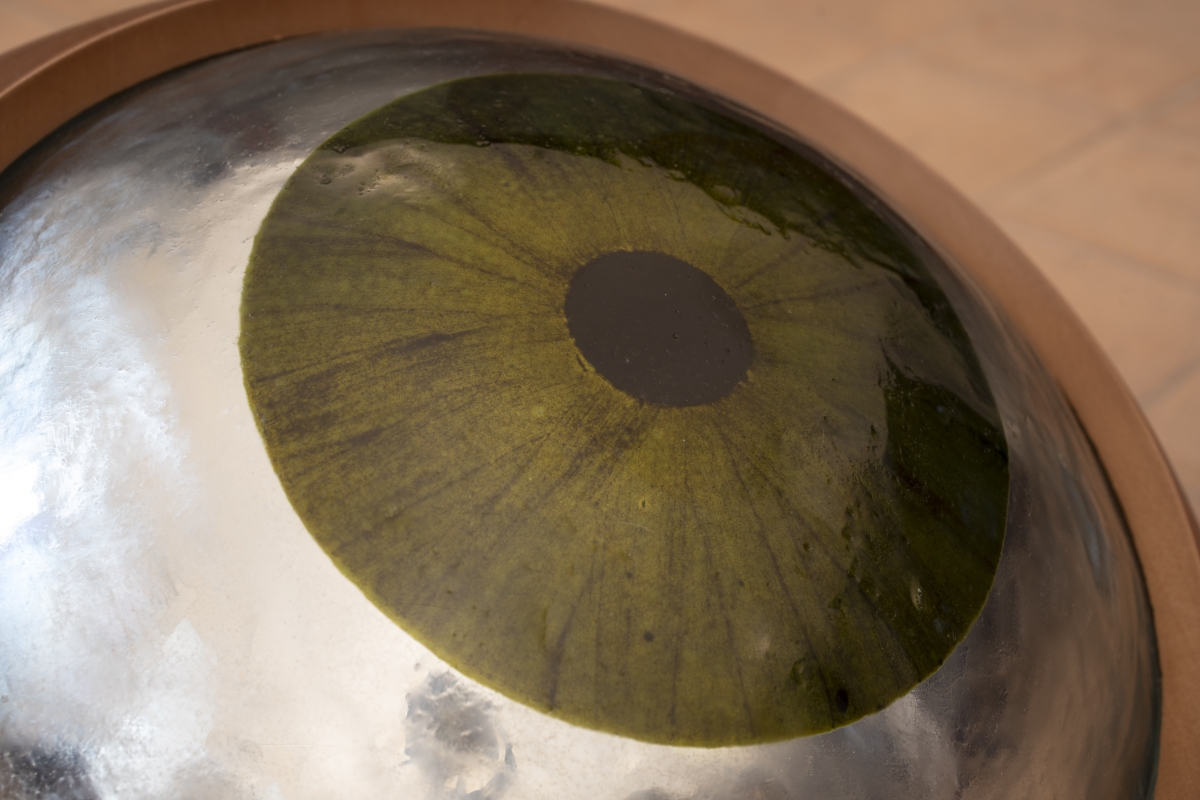

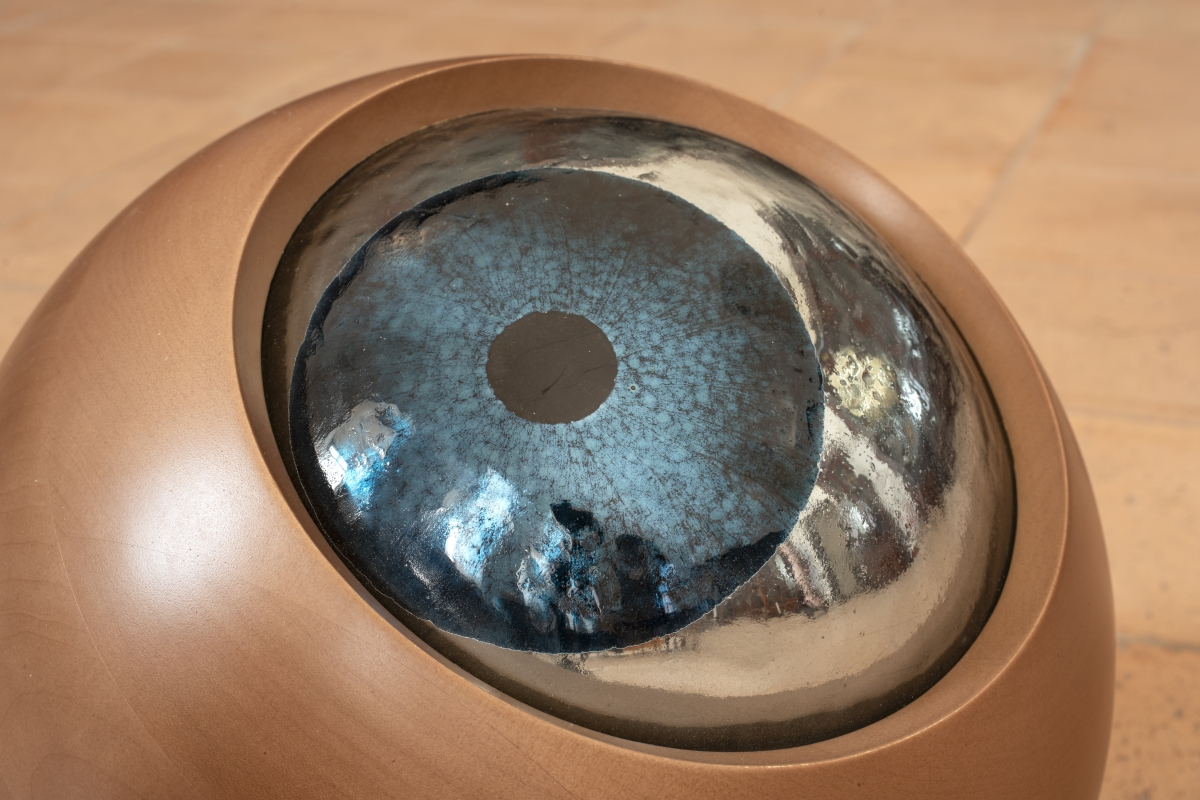

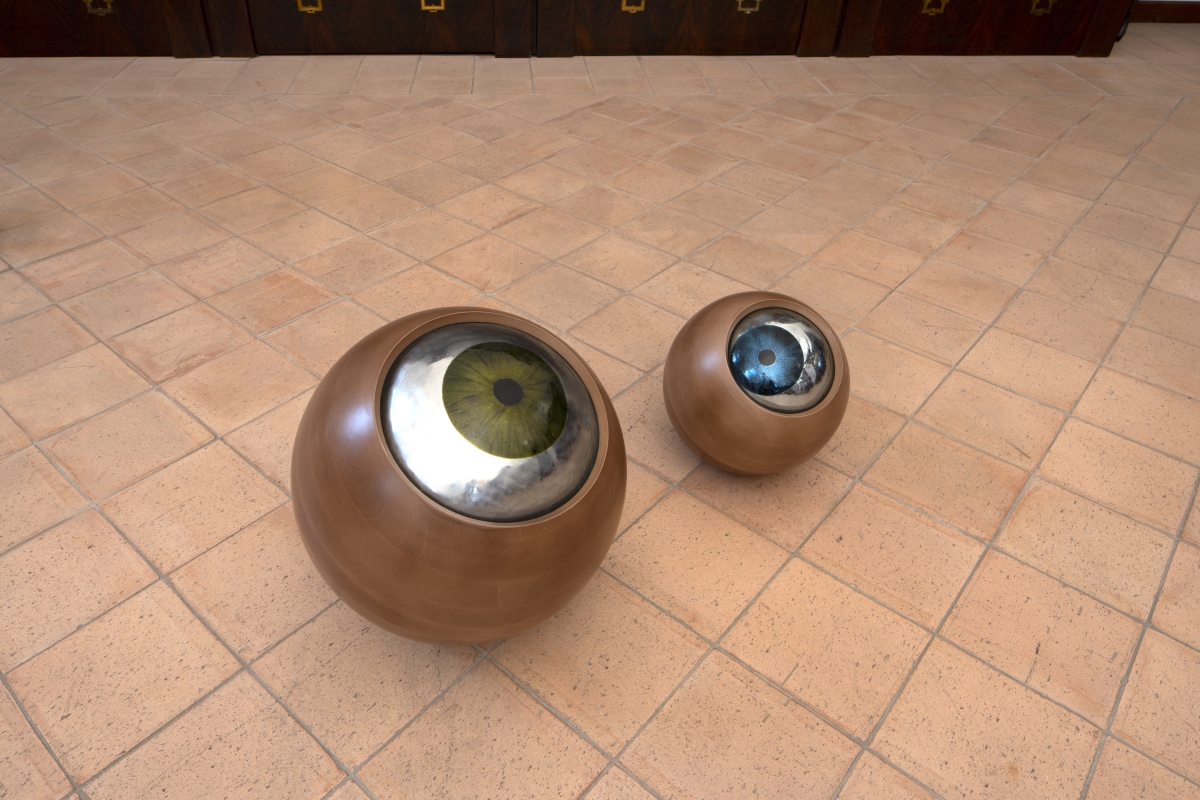

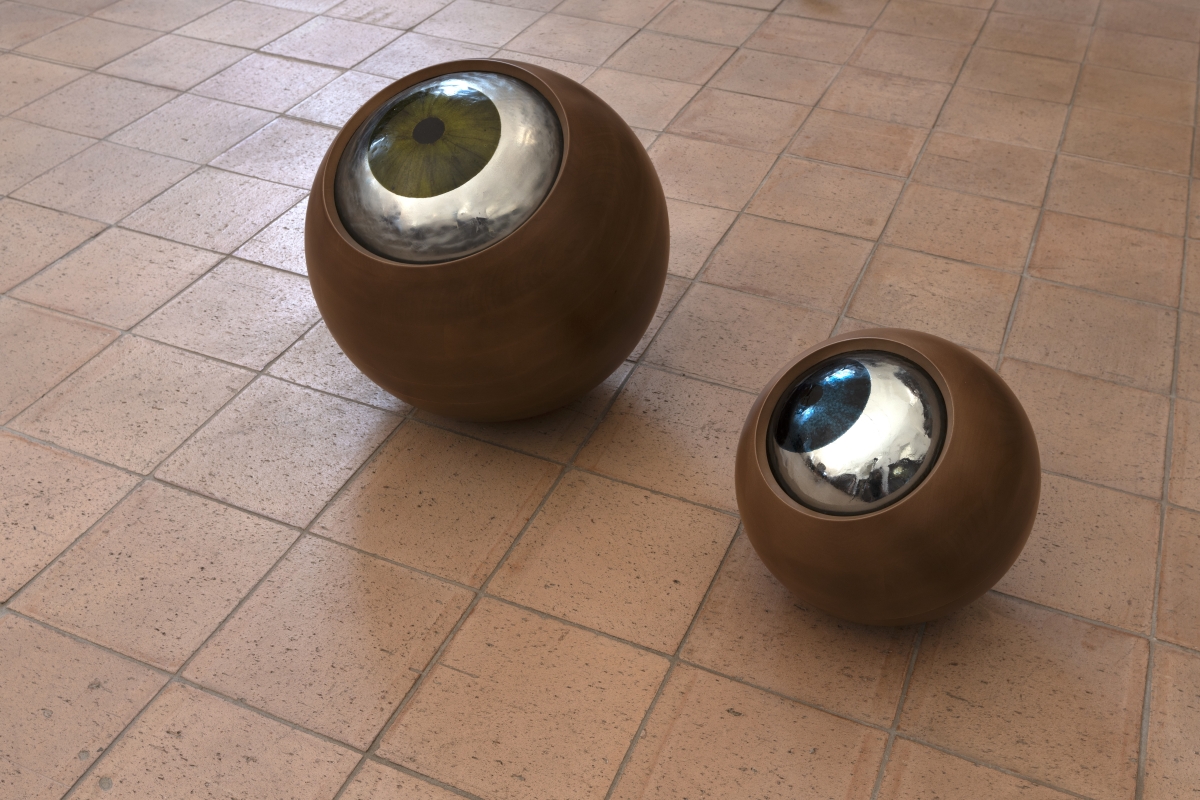

Optics, physical-chemical transformations, and geological phenomena are the focus of the works presented by the artists, who in some cases evoke the functionality of the scientific instruments, while maintaining an ambiguous form. This occurs in Marta Frėjutė’s sculptures, which are inspired by the representation of optical phenomena, from the seventeenth-century Torricelli Lens in the royal collection to the large Fresnel lens, also known as the “stepped” lens, built in Paris around the 1840s by the famous lens maker H. Lepaute and used by Melloni to demonstrate the calorific power of moonbeams. Because of its great refractive power, the Bourbons installed this type of lens in lighthouses on the coasts of the kingdom. The large lens is an attraction at the Museum of Physics: in fact, anyone mirrored in it appears deformed, hopelessly awkward, and “wrong”. The artist captures this disorienting sensation in her sculptures, which simulate two oversized eyeballs, with lenses applied to their surface that simultaneously reflect and absorb light. As an alienating presence in the Museum, mysterious as tools whose function is unknown, these sculptures deceive the viewer, revealing their profoundly elusive nature.

Ona Juciūtė’s sculptures also play at disguising themselves with museum artefacts. They appear to be wooden objects, but have actually undergone a process of material transformation, turning them from wood into mineral, making them fossils that are thousands, even millions of years old. During this time, through a well-defined process of “replacement and infiltration” (concepts akin to the artist’s very actions in the Museum), the wood’s molecular structure changes irrevocably, although its exterior form is intact. The artist collected objects with these properties, buying them on different online platforms. Many of them were sold as chakra healing tools, based on beliefs mixing the scientific and the spiritual, by virtue of their connection with the Earth’s energy and associations with rootedness, stability, resolve, determination. These objects interrelate with small bases made of chewing gum casts: amorphous structures that recall, in an ironic way, fossils of our present time and that, like the shapes in petrified wood, have undergone a profound alteration. Similarly, textile fragments shaped by heat insist on the meaning of trace, taking unexpected forms that materialize sources of energy.

Finally, Simona Žemaitytė directed her attention to geological phenomena, specifically the area of the Campi Flegrei, which sees its volcano awaken from time to time and sometimes causes concern, as it did last year. Several instruments in the Museum of Physics attempt to capture and measure this uncontrollable phenomenon, showing how even the efforts of human intelligence must in some cases bend to the unpredictable forces of nature. Žemaitytė’s perspective then slips into the creases of this extraordinary landscape, between the craters of Monte Nuovo, Lago d’Averno, and Solfatara, using various image-capturing tools (thermal camera, kaleidoscopic and micro lenses), showing how life unfolds in proximity to the volcano and alternating micro and macro views. The outcome is a series of visual and in-motion notes that provide an unexpected view of this enthralling, mysterious, and potentially dangerous scenario.

In this collection of objects and observations, the material and immaterial dimensions chase each other, overlap, and intermingle, to show not only how physical phenomena manifest themselves through instruments born from human minds and hands, but also how art in turn can become a vehicle for the revelation of an idea. It is here, perhaps, that the collision between art and science becomes a communion of purpose: the investigation of reality and of its expressions that can constantly generate new perspectives leading to ideally endless experimentation.

Text by Alessandra Troncone

Collisions

Artists: Marta Frėjutė, Ona Juciūtė and Simona Žemaitytė

Curated by: Alessandra Troncone

Museo di Fisica, Via Mezzocannone 8 – Naples (IT)

May 10 – June 30, 2024

Collisions, installation view, 2024. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, A Great Variety of Habits, 2024, sun bleached textile. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Collisions, installation view, 2024. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, A Great Variety of Habits, 2024, sun bleached textile. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Zona rosa, 2024, thermal video with sound, 10’11”. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Marta Frėjūtė, Untitled, 2024, wood, glass, mixed media. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Collisions, installation view, 2024. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, A Great Variety of Habits, 2024, sun bleached textile. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, A Great Variety of Habits, 2024, sun bleached textile. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Ona Juciūtė, Replacement and Infiltration, 2024, petrified wood, acrylic resin. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Close – too close, 2024, video with sound, 12′. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Close – too close, 2024, video with sound, 12′. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Close – too close, 2024, video with sound, 12′. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Close – too close, 2024, video with sound, 12′. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Zona rosa, 2024, thermal video with sound, 10’11”. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Zona rosa, 2024, thermal video with sound, 10’11”. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Zona rosa, 2024, thermal video with sound, 10’11”. Photo: Maurizio Esposito

Simona Žemaitytė, Zona rosa, 2024, thermal video with sound, 10’11”. Photo: Maurizio Esposito