On 9 February, Gustas Jagminas’ exhibition Poetic Testing Station 1 opened at the Vilnius city gallery Meno Niša. This is the painter’s eighth solo exhibition, in which he displays his painterly experiments with paint, plasticity, plots, and fields of meaning.

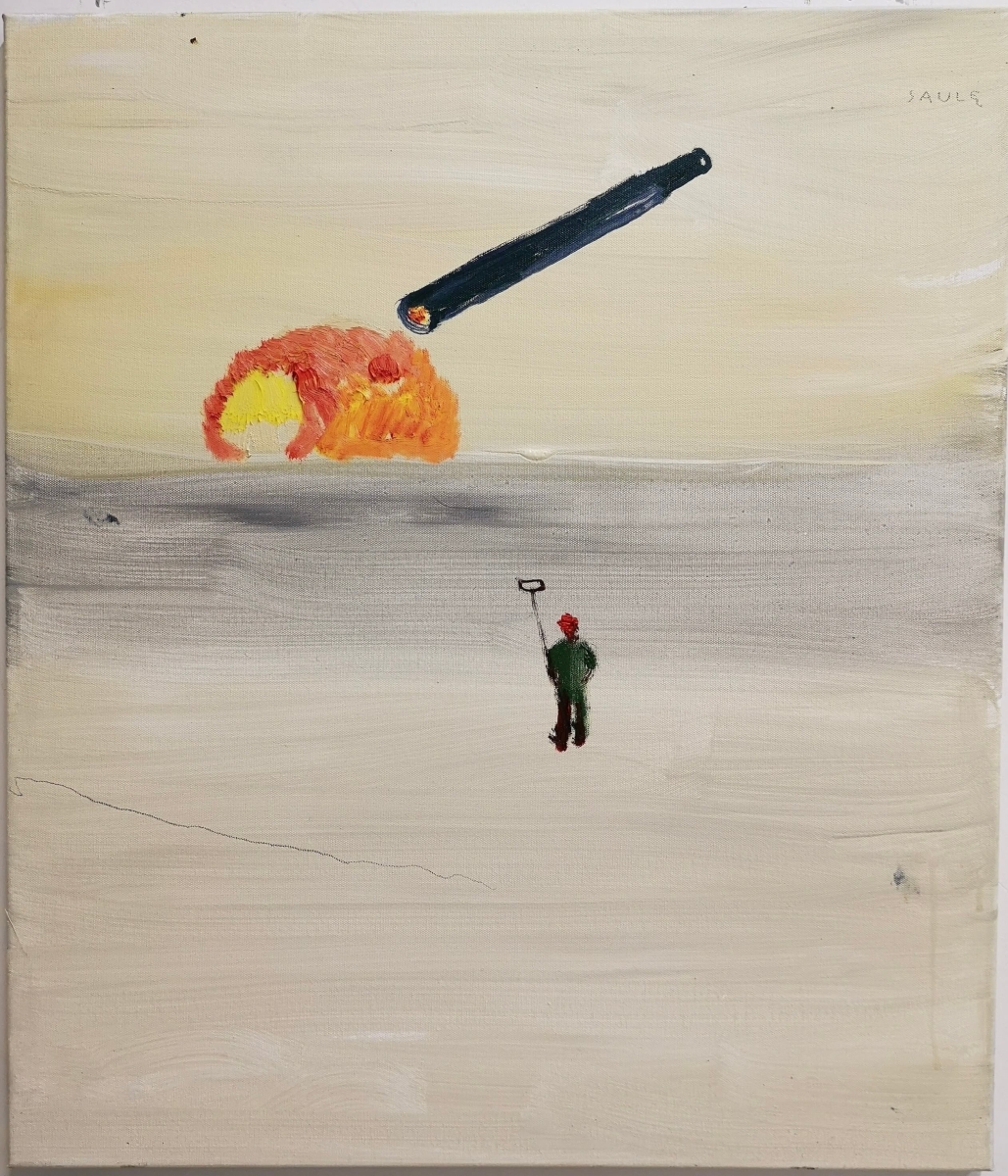

Rosana Lukauskaitė: In one of the paintings in the latest exhibition at the Vilnius city gallery Meno Niša gallery, a man appears to be taking a selfie against the backdrop of the end of the world. How has the mood and subject matter of your work been influenced by the past year, when the world has been ravaged by plague and war, and when apocalyptic moods have run rampant?

Gustas Jagminas: Generalizations about how one or another period has influenced my work can be made a year or several years later. In this case, two years later, I noticed more color and light in my work. I tried to portray the moods of the time I lived through in a less obvious way, without avoiding the surreal. The subjects of my paintings seem sinister only at first glance. For example, the painting you mentioned is called Looking at the Sun and it shows a man holding up a device that perhaps controls a binocular or telescope pointing at the sun, although the first impression might be that it is a depiction of an atomic explosion. I have deliberately left ambiguity in many of the works. As in the title painting of the exhibition, Poetic Testing Station 1, two figures are crawling into the rockets. Of course, this could be a reflection of the brutal war in Ukraine, but it is also possible to see here a strange testing ground or a rehearsal of some kind of performative flight with dummy rockets into space, without even ascending… because space is here, it’s everywhere, and we are in it. After all, similar dummy rockets stood absurdly in the playground of almost every block of apartments in my childhood.

RL: Your paintings (and their titles) are not lacking in irony. You have said that “it’s usually some kind of problem that leads to creativity.” What role does reflection on societal problems play in your creative process? Can an artist make a difference, or is it up to the artist to draw attention to the issues and laugh with the viewer?

GJ: I don’t know if an artist can make a difference, but they can reflect on the problems of society. You are always a citizen as well as an artist, and you can act in more than just the creative sphere. Even just reflecting on contemporary issues can be meaningful.

RL: Your work is dominated by abstractions and landscapes that flow into each other. I have read that you find subjects for your paintings during walks. Already ancient philosophers treated walking as a way to generate new ideas. Is the spirit of the flâneur (observant stroller) close to you?

GJ: Walking is very important to me, and I try to walk a good distance every day. My second solo show was called Idlings and it was about just that. When you walk, the plots of the paintings start to come together, but it doesn’t necessarily come from what you see – it just comes from thoughts. Often, even if you’re walking along very ordinary routes and you don’t see anything very new or inspiring, the very act of walking, the rhythm, the pulse of life, stirs you up inside and gives you ideas that you might not have had while sitting in the studio.

RL: So you are inspired by the natural world and its elements. How does this influence manifest itself in your abstract paintings?

GJ: When I paint, the painting usually starts with sky and earth components. Very rarely in a painting do I abandon that. Then there is some kind of action going on between the sky and the earth. The landscape itself as a leitmotif is very important to me. Usually, the painting starts from some kind of state of mind that creates what is happening in the landscape. In my case, the landscapes are not very urbanized, on the contrary, I prefer wastelands. I’m very fond of chaotically overgrown Lithuanian shrubbery. In my latest exhibition, there is maybe only one such work, but I have a series of them. In the summer, it is very important for me to paint from life in nature – I carry a sketchbook, choose a motif, and work there. Usually, I avoid showing such works in exhibitions, but they are very important to me because when you have a live relationship with real images of nature, the content of the paintings is easier to form when you go back to the studio later.

RL: In an interview, you considered that “maybe only painting will remain. Maybe I’ll just paint painting, the content of which is painting.” In the context of contemporary art saturated with performativity, installations, and the constant input of media, painting seems to be experiencing existential questions that encourage it to constantly reinvent itself. How do you maintain creative purity and loyalty to the easel, canvas, and paint?

RL: In an interview, you considered that “maybe only painting will remain. Maybe I’ll just paint painting, the content of which is painting.” In the context of contemporary art saturated with performativity, installations, and the constant input of media, painting seems to be experiencing existential questions that encourage it to constantly reinvent itself. How do you maintain creative purity and loyalty to the easel, canvas, and paint?

GJ: It’s not difficult because it’s a choice. In preparing for this latest exhibition, I realized that I don’t really enjoy exhibiting – all the hustle and bustle and being seen is very tiring. But you have to do exhibitions to see your work from the side and to get encouragement or criticism. Most of all, though, I just want to paint. Painting is like a very specific language. It can convey certain things that would otherwise be impossible to communicate. When you have been using this language for years, you want to continue and “read” the works of other colleagues. Here I am echoing a thought by the painter Arūnas Vaitkūnas, which is very deeply etched in my memory. And the myth of the death of painting is itself long dead. It was floating around in Lithuania some twenty years ago. Now it is as if there is a kind of renaissance of painting. It seems to me that painting will always be around, as long as there is a human being, but maybe the forms, the means, and the paints will change. There are already computer programs that compose music more harmoniously than a human being, and there have even been experiments where, if you invite an audience to a philharmonic hall, they are played this music without being told who the author is, or they are tricked into believing that it is some unknown Beethoven sonata, and then they are played the music of the real composer. The strange thing is that the audience usually prefers the first composition. However, this does not negate the music itself, because it is first and foremost a way of communicating, of feeling each other. Just as it is interesting to play a game of chess, it is also interesting to create something. I don’t think that painting is lacking attention now. It’s true that the circle of people who can “read” painting may have shrunk, but they are still there, and you can always talk to your colleagues. It is even said that there are two schools of painting in our small Lithuania: Vilnius and Kaunas, and these schools even have some differences! I think that painting has been and will be around.

RL: Continuing on the theme of technology and computer algorithms that you mentioned, I would like to ask you how you feel about the images created by artificial intelligence, which are forcing you to reconsider questions of authenticity and authorship.

GJ: What I find interesting and surprising is not the results or the authorship of such creations, but the technological progress and how far it has come. As in the case of music, it is not the compositions themselves that are more surprising, but the possibilities of information technology. I think that this is a completely different field, which is adjacent to art but will never replace human creativity. Linguistic algorithms that can learn from the Internet can do a pretty good job of composing poetry, too. I think that there will be more and more of these cases, and perhaps they will contribute to technological development. There are already mechanical machines that paint. Their software also “creates”, but it will not replace the things that humans create.

RL: Your paintings are full of images of power lines, poles, and transformers. What do these networks of voltages and currents mean to you? What is most electrifying in your creative life?

GJ: Often, while walking in the typical Lithuanian landscape (I am often in Dzūkija, in the town of Daugai), I come across electricity poles in the hilly fields, as if in the wild land, untouched by reclamation. It is like a sign of civilization. While there, you can even hear the poles making a buzzing sound. In these images, I am not talking about electricity per se, but about man-made, completely uninteresting, and banal installations, which, like archetypes, have a strong impact on the landscape. A similar sense of landscape can be found in the photographs of Remigijus Pačesa and the paintings of Algimantas Kuras. Crosses are also signs of this kind of influence, and when they appear in the landscape, they immediately create tension. And in my creative life, the most electrifying thing is life itself.

RL: You mentioned R. Pačėsa and A. Kuras, and in one of your paintings, you painted a window with a view similar to a Rothko painting. What other artists inspire you? Maybe the ones that had the biggest influence on you as a young artist are still close to you today?

GJ: The Lithuanian painters have been my biggest influences, and the things that inspire me are usually things in painting that I don’t practice myself. For example, Paul Klee has been very interesting to me for the last two years, and I never get bored of him, although his painting is radically different from mine. I often flip through his album. And because he was an extremely prolific artist, who left a lot of work, I follow several Facebook pages dedicated to him on the Internet, where every day I see something new and surprising. I am inspired by Klee’s musical works and by his freedom to construct deep, felt, and crafted paintings out of seemingly simple, childish details. And of those artists who were important in their formative years and remain so today… I would have to name a dozen Lithuanian painters.

RL: You have mentioned reading as an important part of your daily routine. What book or books are currently on your bedside table? Are the works you read later reflected in your work in any way?

RL: You have mentioned reading as an important part of your daily routine. What book or books are currently on your bedside table? Are the works you read later reflected in your work in any way?

GJ: I’m currently reading The Story of the End of the World by Matas Maldeikis. It may be a very resounding title, but it is a very serious book about the geopolitical situation in the world today. And because the author is Lithuanian, a lot of attention is paid to how it affects Lithuania. The other book is Sigitas Geda’s Green Parchments. Diaries. I usually read more than one book at a time. If I want to think about the problems of the world, I choose more historical, anthropological content, but there is always fiction alongside it. The literature I read doesn’t usually translate directly into paintings, but it gives rise to all kinds of inner impulses that become the impetus to paint one painting or another.

RL: Poetic Testing Station 1 is your eighth solo exhibition. Is Poetic Testing Station 2 also in the future? What series are you working on now?

GJ: I’m not sure about Poetic Testing Station 2 because I form a series based on new searches in painting, and what happens to me at that moment is very important both in my personal life and in relation to what is happening around me. I’m not thinking about another solo show right now because I’ve had quite a few lately and I’m feeling tired. Sometimes I envy such painters as the Lithuanian painting classic Antanas Samuolis, who held very few personal exhibitions during their lifetime. Now it has become customary to hold personal exhibitions every year for artists to remind others of themselves, show what they have created, and present a kind of report. It seems to me that it is not necessary. In recent years, I have had to hold personal exhibitions more often, whereas before I held them only every two or three years.

Photography: Meno Niša gallery