Valentinas Klimašauskas: Hello Goda,

Goda Palekaitė: Hi Valentinas,

VK: Having in mind that our conversation is happening during quarantine, what would you say to a Covid-19 denier?

GP: I’d rather not dismiss conspiracy theories. I haven’t met any Covid-19 deniers myself, however, your question makes me remember an exhibition I made last year together with Swedish performance artist Annika Lundgren. She told me a lot about the Flat Earth Society whose apologists deny that the Earth is spherical and believe that we are all victims of governmental interventions, contemporary science, globalisation and the war industry. While, according to them, their own reasoning stems from an old tradition, is based on complex research and is supported by scientists as well as a certain secret (yet widespread and active) society. They are constantly updating their research in order to verify their claims, including drawing maps of the flat Earth, publishing articles and so on. It is possible and even likely that the topic of Covid-19 will cause the exact same mistrust in the governments, science and media and that new organisations with their own logic and argumentation will be set up. In fact, such parallel realities are in close proximity to us, we are simply too blind to notice that not everybody thinks the same way as we do. For me, as an artist, it is important to continue discovering how else our world can be perceived.

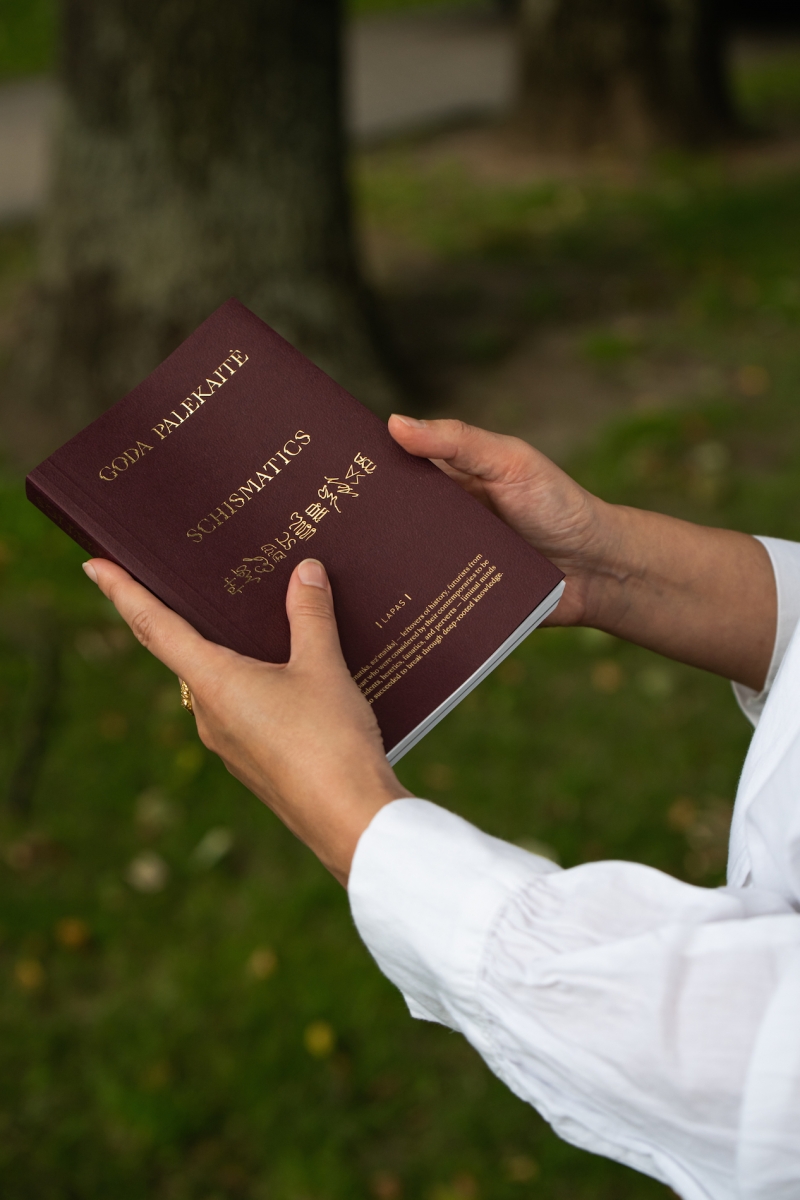

VK: Isn’t this topic relevant to your book Schismatics and who are the ‘schismatics’ to you?

GP: It is very relevant. I employ the old fashioned religious term ‘schismatics’ for my own use. To me, it signifies historical characters who were ignored and left out from the official historical narratives, the ones who envisioned alternative realities. The majority of them were deemed as conspiracy theorists, mad people or perverts, for example, Sappho, the first female poet known to us today, was stigmatised while her artistic work was destroyed because she was a woman, a homosexual and a poet. Or Emanuel Swedenborg, the accomplished scientist who started seeing visions of heaven and hell so vividly and in such detail that he could describe them in a scientific manner. On the one hand, while writing Schismatics I was eager to collect historical pieces into a character’s portrait without glorifying any factual information – instead trying to highlight my personal relationship to him or her, our shared dreams, desires and inner transitions. On the other hand, schismatics have helped me realise how far the thoughts can be traced, and so to finally abandon the illusion of authentic creativity – they’ve helped me see that my own thoughts stem from them people of whom I know so little, of whom recently I haven’t heard at all, and some of whose existences I even doubt.

VK: Back to the topic of quarantine, isn’t this period especially inspiring for the act of writing? Couldn’t this quarantine be that L’Écriture du désastre of Maurice Blanchot – an additional incentive to focus, even to create new ways of writing in the face of our rather frightening world?

GP: Hasn’t it been long proven that disasters tend to inspire artists, writers and thinkers? I’ve been investigating an unpopular writer from the beginning of the 20th century, Essad Bey, an Azerbaijani Jew who later converted to Islam. He grew up in Baku and, before fleeing to the West with his father, observed how the Bolsheviks were destroying the city and how citizens of different ethnicities were slaughtering each other. I cannot proof that this was the case, but in my interpretation, Essad decided to become a writer as he was watching books being publicly burned – particularly in that moment when the books and their words turned into something else entirely.

Another exciting character was M. Blanchot’s good acquaintance (however, they never became friends) French anthropologist and writer Michel Leiris, who’d had a great influence on Blanchot. In 1931 Leiris was selected to take part in the Dakar-Djibouti mission, the greatest colonial scientific expedition of the time. While travelling through Africa as a colonialist he began to see the “disaster of colonialism”; one could say in this he was ahead of his time. He published his chaotic, nightmarish, psychosis and anxiety driven writings, intermixed together with his field notes as a book L’Afrique Fantôme, which was later to become one of the most important works both in surrealist literature and in the postcolonial discourse.

Both examples seem slightly more dramatic than our quarantine at home. (Smiling). However, I am curious to observe the history of our contemporary apocalyptic thought, which is, in fact, as old as the history of humanity itself. Inspired by the first quarantine, last summer I, together with my artist colleague Sina Seifee, released an online dictionary of apocalypse, it can be found here: https://dictionaryofapocalypse.com/

VK: Having considered the signs and font of your new book, I’d like to ask: What is your relationship with language, with letters and signs? Perhaps you would know how certain intentions turn into writings, or where thoughts come from?

GP: That’s an interesting question: where do thoughts come from? (Smiling). And why do they sometimes explode like fireworks while at other times are dead silent or emerge as some utter nonsense? I once had a professor who’d say that thinking and thinking-contemplating are two very different things: if you are thinking, it doesn’t mean that you are contemplating that which you are thinking of. Interestingly enough, in English, as well as in German, the difference between these two concepts isn’t as clear as e.g. in Lithuanian with two distinct words galvoti and mąstyti. Does that mean that the Germanic language speakers can’t understand this thought while we do? My relationship with language takes up a very important place in all of my creative work, not only in my texts – perhaps that’s why Schismatics is concluded by Monika Lipšic’s riddle about language. Letters to me are like jewellery, miniatures of language. I do not usually dwell on them for too long because the unstoppable stream of language keeps carrying you further along, and so you are left to observe that which you are yourself saying or writing as though out of nowhere, never before having thought about it. While the jewellery of Schismatics was carried out by a very sensitive designer Vilmantas Žumbys – he created personalised fonts for each of the characters. It was incredibly pleasant to work with him – our differences were only complementing to one another, which rarely happens in life.

Goda Palekaitė, ‘Liminal Minds: Michel Leiris’, installation view from the solo exhibition at Konstepidemin gallery, Gothenburg, 2019

VK: Since we are talking about writing, about the importance of discovering new spaces, perhaps you could tell me more about L’Écriture Feminine in the context of Schismatics?

GP: I like imagining female writers as my intellectual ancestors. One of them is the aforementioned Sappho, who, by the way, used to sing her poetry accompanied by a lyre and who most likely was illiterate. Then after the ancient Greek era my genealogical tree languishes for over a millennium until the tradition of Christian female mystics gets distilled. I am currently investigating their lives. In academic studies these women have finally come to be perceived as the proto-feminists: Teresa of Avila, Hildegard of Bingen, Saint Thecla, Catherine of Siena, Wilgefortis, the so-called bearded saint (the girl became famous for growing a thick beard overnight after refusing marriage). Their open, exalted and very much eroticised encounters with Jesus enabled them a kind of autonomy and liberation from the oppression of men and the Church. L’Écriture feminine is a term coined by French feminist theorist Hélène Cixous, and to me it is best translated into feminine (hand)writing. French feminists (Cixous, Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray…) think about the body through the discourse and claim that language and history have always been gendered – there is no gender neutral language. Historically speaking, feminine writing would never be equated to that of men, and so it would always have to find a way to leak through the cracks, to permeate, to thwart the prevailing discourse. That’s why we can talk not only about the feminine way of writing, but also about a particular sense of time – the fragmented, cyclical one, existing as an opposition to the linear, logical masculine time flow. Surely, there is no either or – masculine or feminine. I understand L’Écriture feminine rather as a metaphor than as thinking determined by one’s biological sex. In my opinion, for instance, you, Valentinas, know L’Écriture feminine perfectly well. (Smiling).

VK: Is there a way, in your opinion, if that is at all necessary, for us to get rid of various sexisms from our language, to decolonise it? Where should we start – from our relationships or our language?

GP: Perhaps I lack some of that proactive optimism, since I am not entirely sure that political correctness has big success in changing the conservative mentality. In the countries that are founded upon legal premises, where people know which words ought not to be used, what female-to-male ratio should be kept in the workplace or even artists of which ethnicities are the most “correct” to be represented at exhibitions, I tend to observe the exact same intolerance, close-mindedness and conservatism as in our post-soviet states. Although their language seems to have been decolonised, it appears to me that the roots of discrimination are yet elsewhere… I’m not saying that we shouldn’t work on that, since, as it was said by Mikhail Bakunin, revolution is a feast without beginning and without end, and there are no ready-made theories that could save the world. When I am considering decolonisation in the broader sense of the word, I notice a lack of discourse which would connect the dots and juxtapose different forms of oppression, for instance, sexism, racism, homophobia, capitalism, and which would reveal how comparable different mechanisms of oppression are.

Goda Palekaitė, installation view from the solo exhibition ‘Architecture of Heaven’ (curated by Pauline Hatzigeorgiou), Centre Tour à Plomb, Brussels, 2020

VK: At the end of our conversation I’d like to talk about your Ph.D. research at Hasselt University and PXL-MAD School of Arts in Belgium. You are investigating speculative and creative methodologies for historical counter writing – such as fictioning, spatial practices, forgeries and the like – through your own artistic practice and your own texts. Could you talk a little more about your current research?

GP: I am extremely glad about this new doctoral position because it proposes no intentions of transforming my artistic practice into an academic one – instead it wants to hear an artist’s voice within a scientific context. My creative work is my doctoral work. Right now I am preparing for two new research projects which are about to take place this year, if, surely, the vaccine will get materialised into regained opportunities to work, travel and socialise with people. One of them is linked to a character from Schismatics, a 12-year-old girl named Mary Anning who found the first skeleton of a dinosaur back in the beginning of the 19th century in Southern England. She later became a palaeontologist and influenced Darwin’s theory of evolution. It just so happens to be that county Dorset in the South of England has one of the oldest geological strata, having barely changed for over 200 million years. That’s where she lived, and I will be going there to explore the region myself. In talking with scientists from different fields I will try to discover narratives of the early “historians of the Earth” as well as possible links between such narratives and the contemporary theories of the Anthropocene, or, in fact, its critique. The so-called new age of the Anthropocene in which we live is neither new nor surprising in any way – scientists, thinkers, political activists and communities have been talking about the harsh influence on human activity onto our planet for the last couple of hundred years. However, these people would always get silenced and ignored by the ever-new mechanisms of exploitation of the Earth’s resources – these would get coupled with legal and statistical mechanisms, while the nature would get transformed into capital or into some sort of anthropomorphic subject. Therefore, I am interested in grasping the complexity of this problem through the practices of rewriting, archiving, forging and the like. The project is called Anthropomorphic Trouble, and is carried out together with artist Adrijana Gvozdenović and curated by interdisciplinary art and research institution Arts Catalyst in the UK. If all goes well in 2021 we’ll set out on a journey following dinosaurs’ footsteps which would eventually finalise as an exhibition in London.

Photo: Gintarė Grigėnaitė

Goda Palekaitė, from a research project by the Caspian Sea, 2017

Goda Palekaitė, from a research project by the Caspian Sea, 2017

Goda Palekaitė, from a research project in Palestine, 2018

Goda Palekaitė, screenshot from the video ‘Biographic Disobedience’, 2020