The human-non-human relationship is a topic that has recently been given a lot of attention in the field of contemporary art. The global environmental crisis is leading us to think of new ways of relating to the world and nature. Since these are topics that are reflected in my own curatorial practice at Alt Lab, I invited the Irish artist Kira O’Reilly for a talk to learn more about her work.

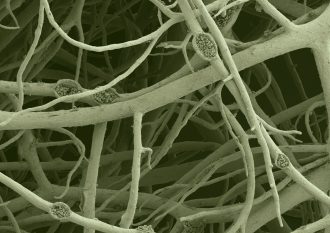

Kira lives and works in Finland, and she was part of an artist residency project in Vilnius, where we met. At the end of her stay, Kira was invited to make a Winogradsky column workshop in Alt Lab, a non-disciplinary laboratory for artistic-scientific research, located in the SODAS2123 culture complex. A Winogradsky column is a way to culture and explore micro-organism communities, which gives grounds to think about the environments and the ecosystems we are part of.

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja

Liucija Dervinytė: How do you see the current state of ecology, and how do you address it in your art practice?

Kira: One of the hardest things to acknowledge is chaos and the unknown: uncertainty. I think that is where artistic practices can be of most value, as ways of being with uncertainty, and to an extent trying to locate oneself and viewers within it.

The best I can do as an artist now is not to try and answer everything, but to acknowledge the multiplicity of voices in the making. I have reservations towards some artists working around ecological ideas, because I feel like we tend to rely on a very limited, though important, canon of books and reading to affirm and confirm ethical positions, without allowing us to work with ambivalence and uncertainty. For myself, I am trying to be a little careful there.

What I am finding with my own practice now is that I want to work with less predictable ways of making, more irrational, more chaotic. What I am not so interested in are didactic messages about ecology that would limit the kinds of work I make.

I find myself looking at Surrealist artists like Leonora Carrington and thinking about her work. For some years now, I have been interested in her short novel Hearing Trumpet, and I am trying to develop different projects inspired by the book. It is a book within a book that invites the unexpected and the unanticipated. It talks about the switching of poles (Earth’s geomagnetic pole reversals). So there is this huge climate event within the book, and with it the sense of the world becomes topsy-turvy and upside down. It also has remarkably interesting narratives around the occult, magical and strange metaphysical laws, and illogics that I think are interesting, curious and provocative. So those are the kind of territories that I find myself drifting towards.

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja

Liucija: Since you often work with other life forms, what ethical issues do you find and how do you address them within your practice?

Kira: The question of ethics has run through my practice since the 1990s when I first worked with another species. I performed a bloodletting piece with leeches. I was doing a series of works of bloodletting from my own body. At the time I was interested in working with old medical techniques of bloodletting. I made several versions of a performance called Bad Humours/Affected and each time I tried to keep leeches alive after the performance. They would live for different amounts of time, but inevitably they would die. So I learned very quickly that my initiation of that performance would always, despite my best efforts, involve the demise of these little slug blood-drinking creatures.

Later, I started learning the techniques of biotechnology, specifically cell culture. I was walking in the footsteps of the pioneering arts partnership The Tissue Culture and Art Project. And this project from the very get-go, from the late 1990s, had been very explicit about the ethical issues in their work and the relationship of working with other bodies, particularly mammalian bodies. So I was working within their discourse, but with a slightly different emphasis. They would talk about scavenging, which I thought was an interesting metaphor, because it invokes ideas about other species, like vultures living of the corpses of animals that have died in the wild. I thought it was a fascinating way to start framing an ethical approach.

I worked with biopsied skin taken from the bodies of pigs used in bio-scientific research. As is the case with animal models, they stand in for a generic human body, hence the pigs stood in for my body. My idea was to eventually work with my own body, but this did not work out in the end. This instrumentalisation of another’s body was part of the ethical relationship. I always found it problematic, and I realised that my approach to working with these ethical considerations is that it will always be uncomfortable. There is never a point of arrival of going ‘that is somehow acceptable’. There is always an acknowledgment of death or suffering and that the species, whatever that is, don’t give any kind of consent, there is no agreement, no approval of that.

Sometimes the word ‘collaboration’ is used when referring to artists working with other species; however, my work has never been particularly collaborative. It is always a very unequal power relationship, and that had been an explicit consideration in my work. That does not mean that those works had been done without consultation. There was another piece I made, Falling Asleep with a Pig with a living pig called Deliah. A very large part of developing that piece was conversations with the producers of Arts Catalyst who were exemplary in this kind of expertise. For example, an expert on animal welfare was involved, who became an advisor for the piece. The artwork was placed in the gallery, and the whole staging was always in consideration of what we felt from our human position to be her most immediate and important needs, and what would give her the least amount of stress.

In other more recent works, I have worked on ticks. It is interesting when in Finland and many other countries you mention ticks and people react with horror and complete hatred, including all of the marvelous people we have who are curators and theorists working around posthumanities. Sometimes posthumanities can appear very romantic and loved-up and all about empathy for other species. But as soon as you mention ticks, there is hostility and hatred. A tick is a particularly important vehicle of provocation without even intending to be. It highlights where people’s triggers are because it is perceived as a threat. Ticks sometimes carry a cargo of pathogens that can have very serious consequences for humans. And as soon as our lives and our well-being are threatened, there is a complete abandonment of ethical responses which are overridden by disgust, fear and loathing. The only exceptions I found were scientists who work with ticks and often have a genuine interest.

It is very difficult for me to think of ethics as something that could create an ultimate reconciliation of well-being for all actors. I do not think it always does. So ethics must be something that is contingent, crucial and critical, but also specific to a time and place. But I say that with an awareness that sometimes we need to have a clear understanding of ethical practices to protect. And ethical practices need to withstand many years. Ethics is also about relations, and that includes human relations and scale.

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja

Liucija: How do you see the future: do you think of it coming on some positive note? Or not so much? People are talking about a fresh start, while others say this might be the end for society. So where do you stand? How do you imagine the future of all these complex relationships will look like? And where does art stand in shaping how we imagine the future, helping us to move in some sort of direction?

Kira: All of your questions are amazing, they are so huge, but wonderful, provocative questions. I will start by acknowledging what you have said. I am not sure if there are more wars now. When I look back on my limited knowledge of history, I suppose it is so often about wars. We do not write about the times of peace. But I feel that my awareness of wars is hugely emphasised and cultivated and is so specific and personal to those who are doing the telling. Like many of the narratives I am following on social media. There is an acute daily granularity of things. It is an interesting way of experiencing war, both rewarding and excruciating.

But in terms of the futures, I find again that I am in a place of uncertainty, and not wanting to set things up too much. One of the things I am reminded of is how I can be absolutely astonished. There is a huge capacity and potential for that. Through astonishment, I connect to ideas and possibilities, and processes that have not been realised or presented previously. Be that ethical, philosophical, societal or technological approaches. There is an enormous possibility for astonishment. And I feel like one of the things I have to do is to leave space for that. For foundational paradigm shifts. We are certainly in a time where at least I feel extraordinary instability. An instability that I have experienced only as a very young person, in the early 1970s. Living in Ireland, in the middle of nowhere, where I was growing up, there was always a sense of nuclear possibility. And now that sense of instability is hugely exacerbated. But I think with that comes a possibility.

In terms of whether there is a place for art within all of that, I would say absolutely. Artists do a number of things, they do innovate. I know that is a problematic word because it is often hijacked by neoliberal agendas. But what I mean is for there to be a genuine sense of possibility, almost standing on the cusp of something, where something is unformed, but to sense incipience. Incipience being what is nascent, what has been forming but has not come to a realised concept. And I think that is often where artists can occupy, spend time with that cusp of something moving from incipience and the unknown into something beginning to form. I think there is a tremendous possibility because artists work with imagination. And that is the territory of possibility. The imaginary is the sense of what has literally not come into being but can and would.

I feel like in many ways I speak in a very old-fashioned way about what it is to be an artist. In an almost naïve way. But I think it is very important that artists feel encouraged, even artists working on a very tiny scale. So that we feel that we contribute somehow. I feel working in any sphere of our lives really, whether it is making artwork or in the daily wonderful mundanity of our lives, there is often this sense of creative problem-solving. Including in our immediate family or our relationships in the communities. So that is probably all I have to say about futures right now. But I like thinking about futures in terms of plural as well. There are many possible futures. The future is so specific to where you are, what kind of society you are in, and what kind of geographical and cultural location as well. Let us see.

Kira O’Reilly is an Irish-born Finland-based artist working across visual art and performance, live art and science, art and technology interfaces, as well as writing. Through her interdisciplinary practice, she considers speculative reconfigurations around The Body. Since graduating from the University of Wales Institute, Cardiff in 1998, she has been giving presentations, teaching and exhibiting her art widely throughout the UK, Europe, Australia, China and Mexico.

Liucija Dervinytė is a visual artist, curator, cultural manager, and co-founder of the Ideas Block cultural organisation and the Arttice platform for cultural networking. She gained a BA in textiles at The University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and is currently enrolled on an MA programme at Vilnius Academy of Art. In her artistic research, she examines a dualistic culture-nature world-view and its implications on the sustainable development of society, along with ways of shaping this complex relationship through art.

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja

‘Winogradsky Column Workshop – Making the Invisible World Of Microorganisms Visible’ with Kira O’Reilly at SODAS 2123. Photo: Gerda Krutaja