At times I get stuck in my own reasoning. I don’t necessarily mean while answering a friend on the tram or explaining a point of frustration (although that also happens). I am talking about thoughts, verbal justifications in the process of making art. Sometimes one just needs to make a bunch of door handles out of wax. Or collect lamps with animals’ feet. But it happens that I’m in line to purchase the 12th one – a fine piece! – but turn around and put it back on the shelf, because, what on earth am I doing? It doesn’t make sense. If I can’t squeeze out a decent reason for my interest in lamps with feet, I shouldn’t collect them, right?

At moments like this, I often think about Eva Hesse. I open Google Chrome and click on the bookmarked link of transcripts from her correspondence with Sol Lewitt. Hesse and Lewitt met at the start of their careers in New York and were long-term friends. When she moved to Germany, Hesse started working in this old, industrial building, where she discovered lots of left-over material. Her paintings slowly turned into sculptures. She gathered rough shapes and wires, which somehow got to her, and started integrating them into the works. While experimenting with a great sense of ambition, the artist would often feel frustrated in the process of not knowing exactly what she was doing, whether it made sense, or in her own words, whether it would actually be ‘good’. Hesse shared these feelings with her friend and fellow artist abroad in letters, in which Lewitt would answer with a dazzling sentence:

‘Just stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder, wondering,

doubting, fearing, hurting, hoping for some easy way out, struggling,

grasping, confusing, itching, scratching, mumbling, bumbling,

grumbling, humbling, stumbling, numbling, rambling, gambling,

tumbling, scumbling, scrambling, hitching, hatching, bitching,

moaning, groaning, honing, boning, horse-shitting, hair-splitting,

nit-picking, piss-trickling, nose sticking, ass-gouging, eyeball-poking,

finger-pointing, alleyway-sneaking, long waiting, small stepping,

evil-eyeing, back-scratching, searching, perching, besmirching,

grinding, grinding, grinding away at yourself. Stop it and just

DO.’[1]

After the big do, he continues calling out the ‘real nonsense’ Hesse should aim for:

‘That sounds fine, wonderful — real nonsense. Do more. More

nonsensical, more crazy, more machines, more breasts, penises,

cunts, whatever — make them abound with nonsense. Try and tickle

something inside you, your ‘weird humor.’ You belong in the most

secret part of you. Don’t worry about cool, make your own uncool.

Make your own, your own world.’[2]

The advice Lewitt offers to the young, doubting Eva Hesse is not difficult to imagine. It seems to me to be something we have all possessed at specific moments in life. As a child, we often just do things. We rely on nonsense, since we are simply not ready in life to rationalise whether things make sense. For God’s sake, we don’t even know what making sense actually means. And so we are in a primal rush to create, to do whatever cool or uncool, to make our own world. According to Tallinn Art Hall, it is necessary for us all to keep the inner child playing in us, as it allows us to continue growing.[3] For the last show before the extensive renovation of their building, the curator Tamara Luuk invites a group of artists who in one way or another embody the notion of play.

First you learn the rules. I walk through the door and am immediately surrounded by pictographic images in red circles. A pair of lips pops up, and a flexible clock. Salvador, is that you? The plaques carry a combination of Estonian artists and international classics. From Dali to Sooster, Da Vinci to Köler. With Traffic Signs, Taave Tuutma inaugurates the exhibition by throwing me into the manual. The work is inspired by the language of traffic. In ordinary life, traffic signs are divided into regulatory, warning and guiding signs. Tuutma chooses the first, which touches conveniently on systematic structures in the art world. The domain, as well as each institution, exhibition, curator and artist on its own, has its set of convictions to follow. Unlike the road, where the signs follow each other in a line at the side, these ones surround me like a herd. This world is not a line, but an area. I see Kaarel Kurismaa’s Still-Life, which is nearly not still since it refers awkwardly a lot like a body to me, inhabiting the field of the exhibition text. Neither is Maria-Kristiina Ulas’ Young Dog in Artist’s Skin a line or one plane, through its multi-dimensional kinetic ways asking for touch.

Play functions in a similar fashion, as it has its own play-sphere. In sport we call it the field, in video games the magic circle. This last term originates from the writings of Johan Huizinga. One of the key writers about play in culture describes the practice of play as moving in a playground which is clearly delineated. This can be either through material or symbolically, intentionally or by habit.[4] They are worlds within a world, and as Tuutma’s work suggests, each has its own course and history. Huizinga compares a playground with a stage, a screen, a court of law, a temple, and accordingly I would like to add, the exhibition space. So I continue and give in to the playground assembled by Luuk, and each practice court of the artists.

Raul Meel takes us into a world and a language modelled from one micro-shape, or more specifically, the inner contour of a razor blade. He purifies an utterly everyday object from a single inside perspective. Blue shapes stand firm against a bright yellow background. They free the potential of this razor’s contour, as their symmetrical or patterned form seduces me to enter another reality. I recognise monuments, work tools and the sensation of a visual illusion. In Childhood Illness, not one, but a multitude of small shapes construct a comprehensible whole. Words are puzzled together in a decisive way to turn into amoebas or cells, floating around in the frame. While talking about world-building through canvas, I direct myself to the cascade of cats by August Künnapu in the next room. The collection of depictions of these animals creates both a community and a public. To practise the practice of painting cats assumes a sense of purpose. It makes me wonder about the world around them. Or gives me a feeling of déjà vu, as if I have seen this before.

One work brings to light stereotypical codes of conduct as well as genuine human urges. In a five-minute video, I watch a black BMW arrive in a forest. What seems to be an anonymous place allows the characters, in suits, to step out of their structure and loosen up by a few minutes of freestyle dancing. Although the dancing itself doesn’t seem to have a routine, the action to shape a moment for relief seems to be well coordinated and planned. I immediately think of a tight business plan and a small gap between meetings. In Dutch, when two functional parts have a gap and there is some lee way, the space between them is called ‘speling’. It is related to the Dutch word spel, or ‘play’. EGO157 by Silja Saarepuu and Villu Pink touches on this small lee way surrounded by productivity as a moment for spontaneity and freedom, and create a small playground within real life.

At times, the real world and the play world not only follow on from each other, they might even overlap. In general, it is hard not to be mesmerised by the abstract shapes and structures in the paintings by Kaido Ole. They appeared at the start of his artistic practice, and have come back again in recent works. I see edges and beginnings, middles and textures. Even though the paintings appear light in their installation, with blended, not too flashy colours, and space between the frame and the picture, they are powerfully present. When I approach the wooden pallets, I feel them tipping over towards me, as if they want to lure me in, or want to add to my own shapes.

Not too far away, a sculpture looks at me straight in the eye. Kris Lemsalu’s Lazy Flower holds up a mirror and rushes me through a world of personas. Ceramic hands and feet surround it like those of a harlequin, which creates a story-like structure and non-structure at the same time. Something doesn’t fit in the logic of the real world. In this non-linear, dreamlike space, action-consequence and me-the other suddenly have a different relationship. Maybe it is because my reflection is hanging on a dark green crane. It is carried by it, sure, but still hanging. I am not fully grounded. When I find out later that the sculpture was inspired by a dream the artist had, the hovering between fantasy and the real world falls into place.

The magic circle is delineated, but it can never be fully sealed off from the reality around it. A contemporary artist, many would say hopefully, is not contained, conserved, pickled, or on water in their own ivory tower. The edge of their magic circle is porous and continuously lends and appropriates from the real world. This lending can generate a sense of public doubting and can become an artistic practice on its own. Here I look at Art Allmägi’s paradise at the end of the first hall. Two figures, Adam and Eve, no doubt, are in front of a gate. It is as if they are guarding the tree, which is surrounded by a bunch of half-eaten apples. Simultaneously, I notice Greek pillars and ornaments, which divest me of my assumptions of a biblical classic. The structure of the grass-carpets and their position with regard to the tree appear to be the start of a French garden. Allmägi is known for creating fictions by means of political and historical happenings, and in this case does no less by juxtaposing various aspects of art history, subtly, in peaceful scenery, and confronting me with the title Back to Paradise?.

Visitors are directed to this garden by Robin Nõgisto’s Hopscotch. I can’t help thinking of Carl André’s flat sculptures, tiles or bricks, just on the floor, where the sculpture is asked to become the space. However, Nõgisto doesn’t seem to share the minimalist’s interest in raw material. Starting from an outdoors children’s game, the artist adds an elusive world of pop culture symbols to fall together with the exhibition space. By that, he blends the hardwood floor with a spark of collaged fiction.

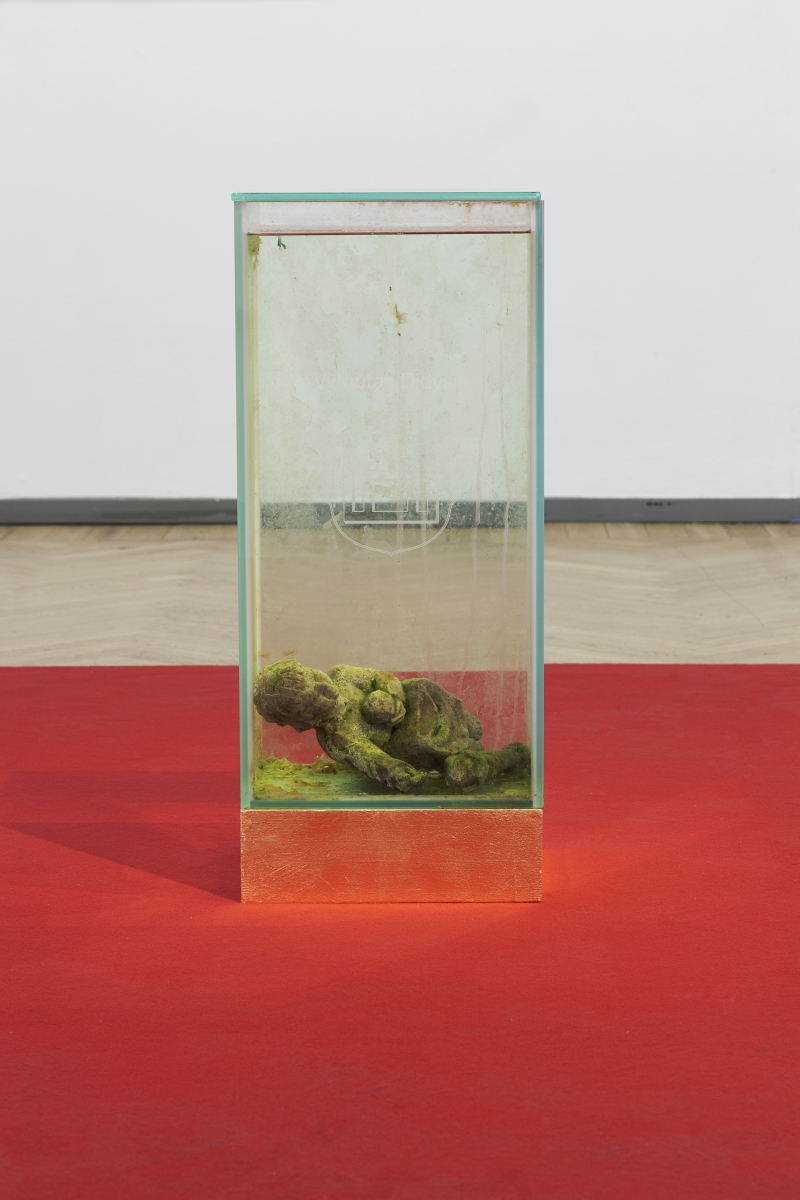

A little further on, I enter a red room. It feels rather holy. I notice the emblem Vytautas, and think about the salty, sparkling water. It seems clear that the parts of the installation are rather charged objects. I find out that the statue in the aquarium is a child figure of Witold the Great, who centuries ago was Grand Duke of Lithuania. The water was obtained from the Black Sea.[5] Starting from both facts and legends, this time in combination with a sacred sculpture from the Art Museum of Estonia, the two artists dive into speculative history, and create both a Chinese whisper and a lie. So they touch impressively on one of the most honourable creative parts of play, which is the element of make-believe.

Our guideline, however, to function and move around in possible, fictional worlds of play, is our commitment and openness to its new elements and rules. Much of this is to be found in the faces of Kolja by Edith Karlson, both a portrait and a self-portrait, and the open arms and deep, piercing eyes of Jass Kaselaan’s Ilja.

But the opening up takes time, and does not always come easily. As Alice Kask is often able to capture the depth of human waters with a sense of weightlessness, I can see doubt in the eyes of the person in the painting. But he keeps staring into the performances streamed in the work by Mark Raidpere. Did that figure open the doors to the video piece? Anyway, he seems hypnotised by the Song of Times. This extremely intimate corner of the exhibition, showing the vulnerability between real and fictional worlds, offers us a different, less straightforward relationship with play.

By accepting doubt and spontaneity, we can go back to that inner child the exhibition text offered us. Most exemplary of this part of us is the artist Marko Mäetamm opening up his process. I feel a spontaneous and silly smile creeping up while I read: ‘Your love is a cake but I am a steak oh give me a break I made a mistake.’ I must say, I am most intrigued by this artist’s sincere opening up to improvisation and imagination. While listening to old Delta blues, Mäetamm says, I quote: ‘Avoiding even the slightest self-censorship and so-called filters, or any fear of making a fool of myself or whatever’.[6] He went on a road of free associations and started creating via automatic pilot. The pilot here is not a machine, clueless about his own doings and solely programmed, but a human being, embracing finger to toe, guilt to regret, mumbling to bumbling. Talking about his piece Love Poems, he finally states: ‘In fact, I cannot explain it rationally.’[7] Just like the inner child, however, he doesn’t have to.

If I give in to the magic circles and courts, I can find little people, Painting, On Earth, At Countryside, and in the exhibition hall. I can find a colourful world on the other side of the Art Hall’s wooden floor. Some worlds’ trees, objects, colours and players might be too literal for me, but overall I am allowed to choose. I find Camille Laurelli’s army of tiny men. Are they cheering or protesting? Could it be both? Is it one group, or is there a duel going on? If I give in, I can actually answer these questions in any way. Tallinn Art Hall in fact asks me to, all of us. While for the last time inserting fiction in the space (and under it!), they not only shushhh us that they’ll Be Right Back. They actually address the visitors themselves, with a soft voice, to Just Keep Playing.

The exhibition ‘We’ll Be Right Back, Just Keep Playing’ is on view until 29 May 2022 at Tallinn Art Hall.

Photography: Paul Kuimet

[1] Letters of Note (2016). DO. Via https://lettersofnote.com/2015/07/06/do/

[2] Letters of Note (2016). DO. Via https://lettersofnote.com/2015/07/06/do/

[3] Tallinn Art Hall (2022). We’ll Be Right Back, Just Keep Playing. Via https://www.kunstihoone.ee/en/programme/we-ll-be-right-back-you-just-keep-playing/

[4] Huizinga, Johan (1955). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

[5] Tallinn Art Hall (2022). We’ll Be Right Back, Just Keep Playing. Dénes Farkas ja Neeme Külm Witold the Great, p. 117.

[6] Tallinn Art Hall (2022). We’ll Be Right Back, Just Keep Playing. Marko Mäetamm Love Poems, p. 119.

[7] Tallinn Art Hall (2022). We’ll Be Right Back, Just Keep Playing. Marko Mäetamm Love Poems, p. 119.