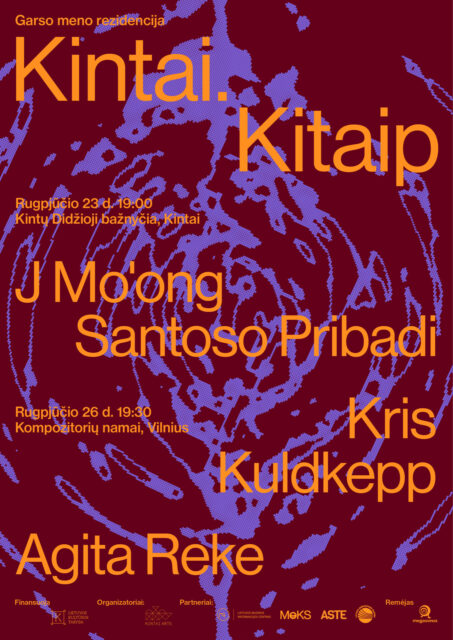

The exhibition ‘Form as Function’, curated by Paulius Petraitis, presents a group of Estonian artists, Paul Kuimet, Kristina Õllek and Ruudu Ulas, who approach photography as a form of dialogue between materiality and conceptual exploration. In these artists’ photographic practices, we encounter the concept of form as an active element, integral to the making of meaning. As we move through the gallery space, we are invited to re-imagine photography as a medium that allows us not only to see the world, but also to interact with it critically and materially, moving through the folds of the surface image, where thought and matter come together to form a concept, a shape, or a feeling.

The exhibition’s title alludes to the tensions between form and function which belong to the history of design and architecture, inevitably conditioning our physical and aesthetic experiences of the objects and spaces we inhabit. The famous phrase coined by the father of the skyscraper Louis H. Sullivan in 1896, ‘Form follows function’, refers to a tall modern office building, an architectural type he developed as a response to the new social conditions and significant economic growth in the USA. An inquiry into such visions behind architectural forms of modernity appears in Paul Kuimet’s 16mm film projection with optical sound Material Aspects (2020) (9 min 14 sec). The film situates the viewer in relation to a tabletop covered with photographs, archival material and books. We are told it belongs to an artist who works on some collages in the 21st century and meditates on the reproducibility of architectural and ideological forms across history. Perhaps the film itself can be approached as taking the form of a collage. Slowly cross-dissolving images and references from various sources open up the filmic surface as a passage, an infinite loop of looking through, which compares forms and ideologies that shape architecture from within, as in Sullivan’s vision of the office tower.

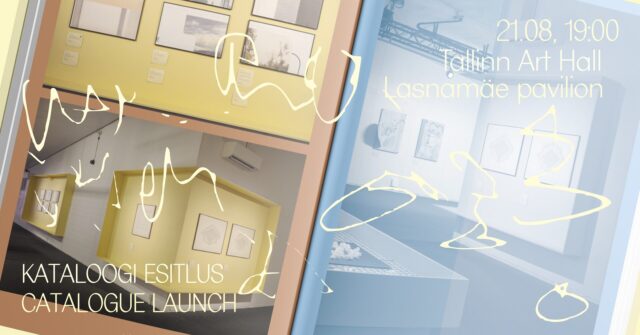

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Paul Kuimet

The film begins and ends with the first sketch for the Crystal Palace by Sir Joseph Paxton, who designed the building for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. This innovative and transparent modular construction made of glass panels and steel serves as the film’s visual and conceptual foundation for exploring the development of global capitalism and its trajectory towards ephemeral finance capitalism today. The opening image of the Crystal Palace slowly cross-dissolves, revealing a fractured iPhone screen, followed by other visual references of soaring glass towers in Lower Manhattan. The narrator tells us that the world is claimed to be more transparent than ever. Information is available at the fingertips, by touching a liquid crystal display: a surface where the world constantly rearranges itself through words and images. This illusion of immateriality and change refers to flows of capital that remain elusive but incorporate almost everything that makes up the material aspects of our lives. In addition, the 16mm film projection technology itself refers to early media of projection (the camera obscura and magic lantern), which, at the turn of the 18th century during the financial revolution, provided cognitive tools to shape the world as an object of speculation, becoming immaterial and subject to sudden change. The prototype of the Crystal Palace is an example of a nearly immaterialised building containing the World Fair inside. It is a vision of modernity that has been reproduced as corporate buildings and suburban shopping malls dotted around the world. This architectural vision of a glass building is also featured in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We (1920), which imagines the future of society inside a glass structure designed to assist with mass surveillance. Towards the end of Material Aspects, an architecture magazine from September 2001 is introduced as an editorial coincidence that has become a historical marker. In this issue, dedicated to skyscrapers, a totalitarian vision of Stalinist high-rises is also featured as echoes of historical crossroads referencing a premonition of Zamyatin’s novel. The film ends with an image of the ruins of the World Trade Center cross-dissolving into Paxton’s sketch of the design for the Crystal Palace, which closely resembles the naked structure of the destroyed Twin Towers. The voiceover reveals the material aspects of the film: synthetic polyester is the carrier of the image projected in front of me. I hear a click. Looking through the surface restarts.

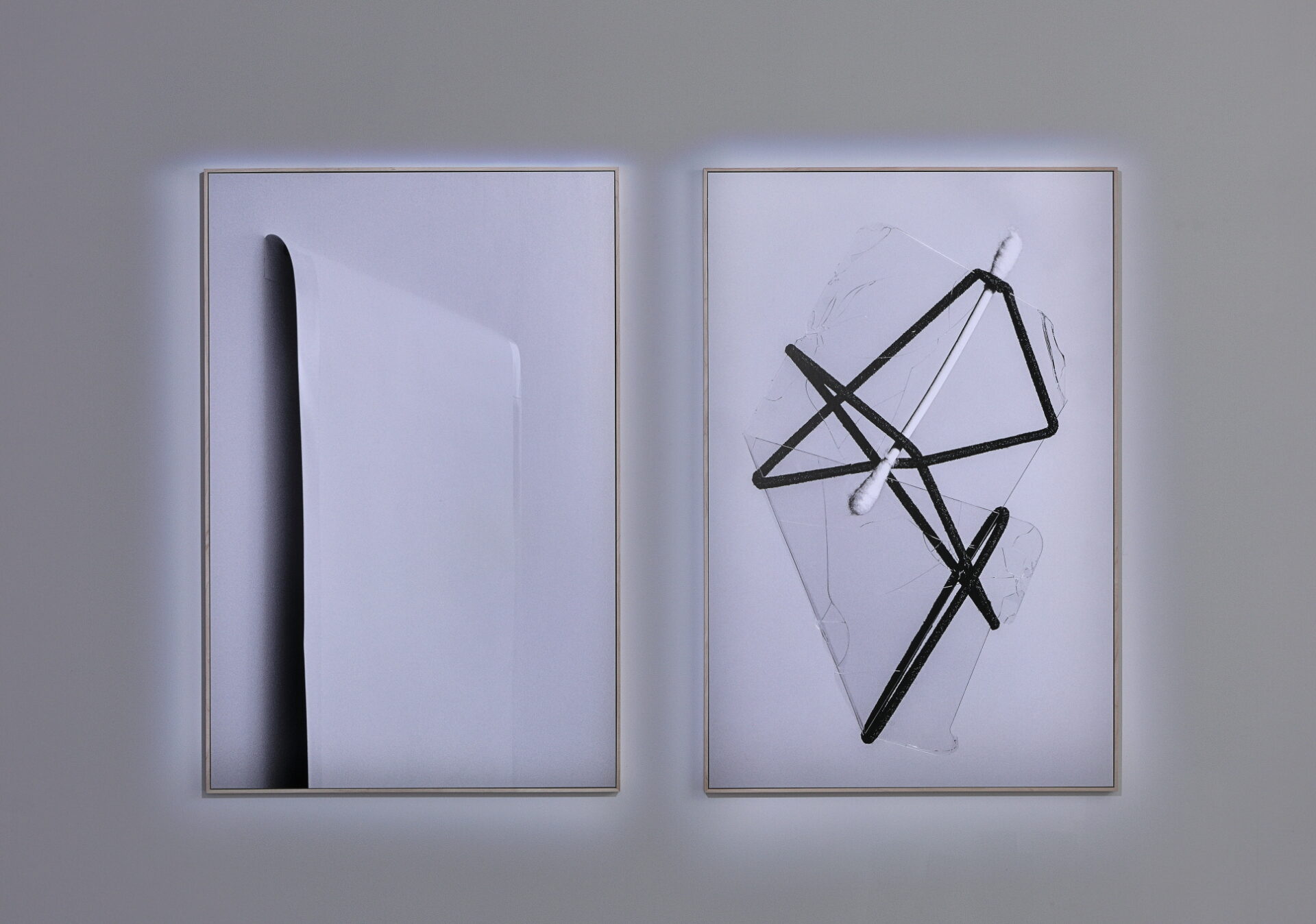

Leading to the projection room, Kuimet’s assemblage pieces What It Is to Be What You Are Not (2022) feature geometric shapes from the grid pattern based on the roof structure of the Crystal Palace. Epoxy resin holds the surface of colourful luminograms together with leaves collected from the palm houses of Tallinn Botanic Garden, which are placed next to the floating geometric shapes formed by light passing through a stencil. While playfully touching on the limits of representation, these herbariums hint at the structures and processes of abstraction. In contrast to these assemblages, the black and white photographs by Ruudu Ulas reframe photography as a site of surface tensions between objects, our bodies, and the spaces we inhabit. In the series Difficult Objects (2021, ongoing), domestic spaces and objects are explored at the intersection of the tangible and the psychological. Each photograph, Framework (2021), Fold (2019–2022) and Tension II (2021), plays with ambiguity and scale to confront and challenge the audience, inviting us to consider our place within the spaces we inhabit. Emerging tensions between oddly placed objects open up gaps where the imagination is activated, while attempting to interpret the connections between the shapes and our bodies. This series also translates something invisible but felt: contemporary living conditions that are marked by anxiety and the unknown in an increasingly unstable and rapidly changing world. Placed next to Ulas’ Framework, Kuimet’s short 16mm film projection Brooklyn Kitchen Still Life (2020) enters a silent dialogue with these difficult objects. The film is a meditation on the passage of time, light, and mundane objects placed in the kitchen, and their slowly moving shadows across surfaces turn the domestic space into a study of still life. Opposite the projection, Ulas’ site-responsive sculptural installation Material Resistance (2020–2024) fills the gallery space with an unfolding photographic image surface. Made entirely of large reused prints and wallpaper, the installation crowds the room and distorts it. Here, Ulas engages with a photograph as an experiential and experimental site, where touch activates the image and turns it into an interactive, material object. This installation engages with the materiality of the photographic surface, which also carries an image of its folds and fractures, thus further distorting our perception concerning its scale and volume in the gallery space.

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

In another room, dominated by shadows of sculptural objects, we encounter Kristina Õllek’s research-based and process-driven practice, which leaks through the boundaries of photography as a medium of representation. Õllek works with grown sea salt, cyanobacteria and green fluorescent pigments to destabilise the frame and the primary image surface, shaping it into a sculptural form, which speaks to slow ecological violence. These objects, suspended in space, appear as fossils of our time, where synthetic and organic materials interact and activate a discourse around marine ecology. Together with marine scientists, Õllek studies geological and chemical changes in the Baltic Sea, which is one of the most polluted and human-affected seas in the world. Complex relationships between the oxygen we breathe and the hypoxic states of the sea, ‘dead zones’, are coded across the works as the shapes and colours of the cyanobacteria. They are etched in glass and the wooden frame covered with silicon, holding an abstract image of a wet and toxic green surface as seen in Surface Accumulation No. 1 and No. 2 (2022). Õllek approaches the photographic surface as a sedimentation of geological time and organic and synthetic matter to activate an imaginary dive into the past and the future of the sea. Large 19-litre bottles filled with water from the Baltic Sea are placed on top of limestone, indicating that the plastic container is a symbol of our time and can already be considered a fossil excavated from the future. The sediment preserved in the deposits of the Silurian period’s Borealis limestone found in Estonia consists of fossilised shells of organisms that lived in the shallow tropical sea several hundred million years ago. The preservation of sea creatures in marine sedimentary rocks turns them into images as traces, which provide information on life that once existed. As the title of one of the sculptural pieces indicates, Silurian Waters Getting Updates on Current Waters (Trilobite) (2023), information about the past, the present and the future of the sea is exchanged between minerals, synthetic and organic matter, chemical reactions, and organisms directly impacted by changes in the ecosystem. In Õllek’s works, this information accumulates on the surface, which is shaped by growing sea salt crystals.

In the exhibition, we move through many different surfaces that open photographic practice as a form of dialogue between materiality and conceptual inquiry. ‘Form as Function’ surpasses the conventional understanding of form and function in the architecture or design sense. Rather, thinking through, with and about the concept of form, this exhibition treats the medium of photography as a material engagement with the world undergoing the process of abstraction. The photographic image here is approached as conditioning the exploration of materiality and touch, without which sense-making of the world would cease.

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Paul Kuimet

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Paul Kuimet

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Paul Kuimet

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Paul Kuimet

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga

‘Form as Function’, exhibition view, Prospektas Gallery, Vilnius, 2024. Photo: Arturas Valiauga