I’ve lately been looking for art that in times of danger and worry invites us not to run and fear, but to stop and find refuge in an in-between state. What are the ways to survive? How to find peace without losing your vigilance? The artist and textile maker Morta Jonaitytė offers a shelter with her work, and at the same time seeks answers to these questions, as she mentioned, while feeling the tsunami growing in the background. Morta presents textile not as plain art, but as complex and story-telling media. The artist graduated in TxT (Text, Theory and Textile) studies from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in the Netherlands, lived in Iceland, and returned to Vilnius a few years ago, where she works in a studio in Užupis. She is currently preparing for a new exhibition in October this year. In this interview, we talked about her studies, the uniqueness of textiles, inspiration, her solo exhibition, and her future plans.

Agnė Sadauskaitė: You took a BA in Text and Textile (TxT) at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in the Netherlands. Why did you choose that course?

Morta Jonaitytė: I entered the academy because of the specific study model. All the students have to do a one-year foundation course (Basic Year) to try out different media, forget their expectations, and search and try to refine their field of interest and expression. The students on the course are divided into separate groups in which they spend the year together. In this way, very different people, with whom you share an intimate space, randomly come together.

The building of the Gerrit Rietveld Academy is like an aquarium. The glass facade and the interior without fixed walls reflect the internal ideology: the studies are built on open communication, sharing and discussion, and the whole academy resembles a common ecosystem. It helped me to find my direction as well. I realised that tactility, observing the world through the surface and moving through it, is important to me in creating, which is why I chose the TxT specialisation.

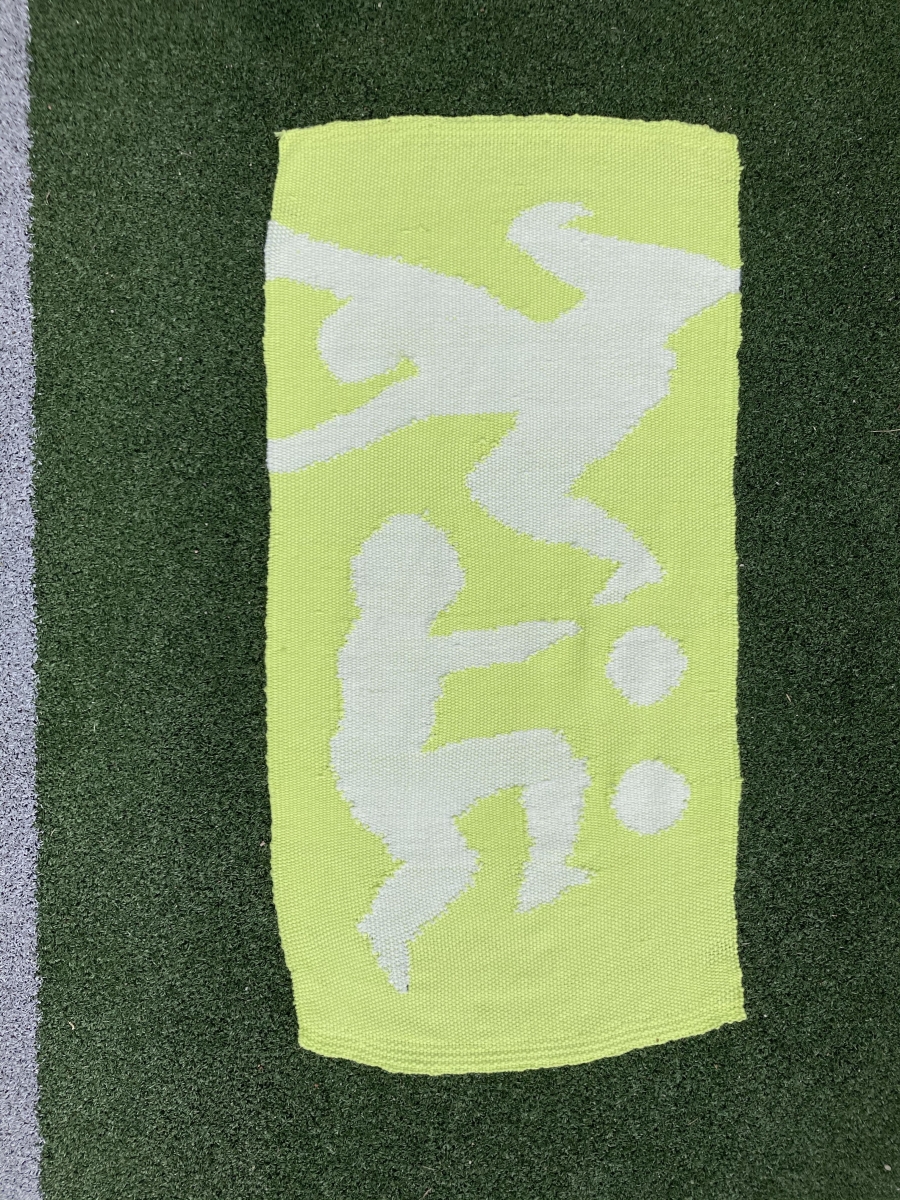

Ghost of a Ball. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė

AS: Were the works created in your Basic Year individual?

MJ: We were set many tasks, both individual and group projects, which had to be completed in a short time. However, the most important part was discussing projects with the class and the teachers. We used garbage, trash, or whatever was to hand. We were encouraged to think sustainably as well, to sort out both our thoughts and the materials we worked with.

When I started TxT, I had time for longer projects. I was able to dig deeper into topics both in conceptual and material solutions. Tessere, in Latin, is a word for both weaving and writing, and the studies are modelled by combining both fields: theoretical written lectures are complemented by practical experiments and technical research. While reading philosophical texts, we constantly analysed how textile terms create a symbolism that is recognisable to everyone. All the students searched for tactility in their own way: through food rituals, voice, performative scenes, clothes or technology. While I was studying textiles, I had wonderful classmates, we became a kind of tribe. Although we were different, we complemented each other and were very close.

AS: How did the combination of text and textiles work? Did the texts have to be related to the things you were weaving?

MJ: We had separate lessons in weaving and writing. We learned to articulate our thoughts by describing domestic experiences or more complex phenomena, which helped to contextualise textiles and give them spatiality. Weaving is a specific practice: sometimes you enter a trance mode, sometimes you meditate, sometimes many thoughts emerge that you want to write down; or, on the contrary, boredom sets in. At the same time, the loom is also a community space. When preparing a loom, you depend on the help of others, you spend a lot of time together, share your knowledge, your gossip, or your painful experiences. This probably gets woven into the works, but the text helps the viewer read what is between the threads … While studying, I got to know textiles as an extremely complex medium. After returning to Lithuania, I noticed that here it is still seen as somewhat flat, although it is slowly becoming fashionable in the context of contemporary art.

AS: What was most memorable in your studies?

MJ: I had various teachers who, being inspiring artists themselves, shared their insights and constantly encouraged me to observe and question the world and myself from different angles. At the same time, there was no hierarchical relationship between us, which encouraged trust and openness. Studying in a different context was a privilege that allowed for continuous improvement. Now I have friends from all over the world, I can get to know our cultural differences; we were constantly learning and trying to support each other. The fact that everyone spends a year together before choosing their main field helps to build up relationships for further collaboration.

Innocence Becomes Shark. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė & Gerrit Rietveld Academy

Innocence Becomes Shark. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė & Gerrit Rietveld Academy

Innocence Becomes Shark. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė & Gerrit Rietveld Academy

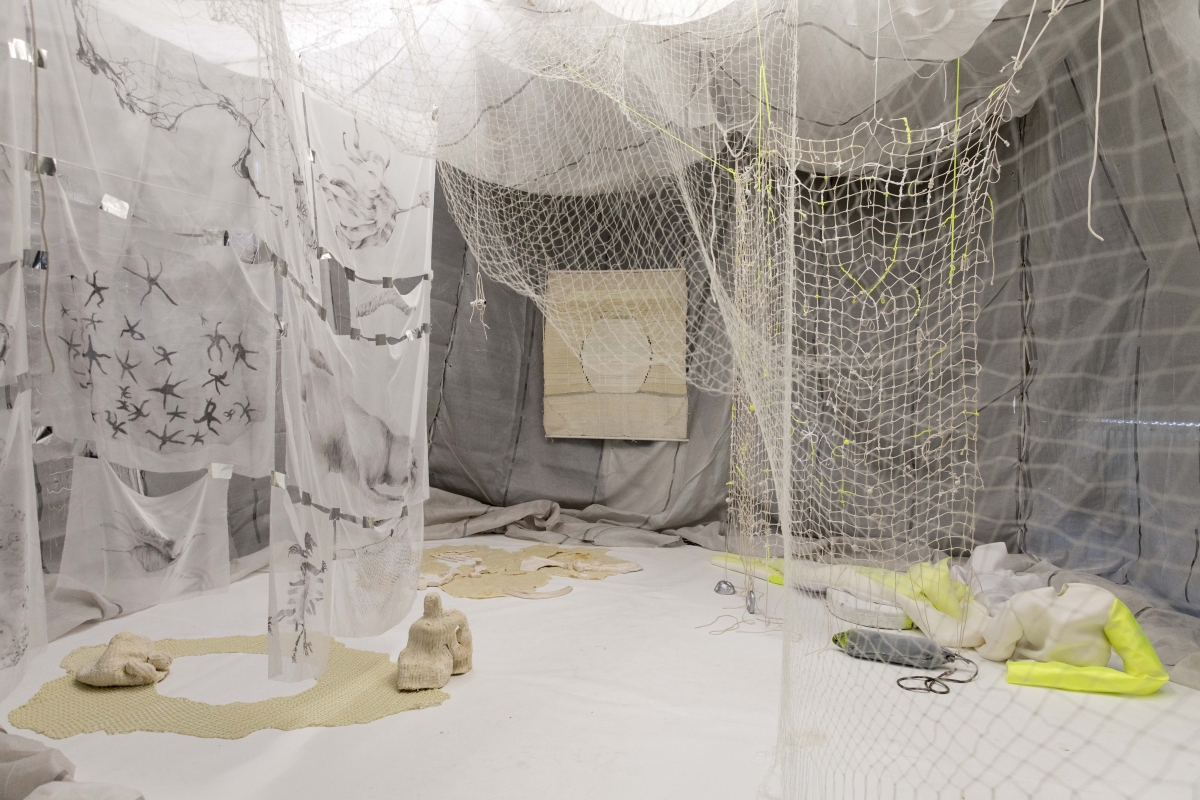

AS: Your final work at the university Innocence Becomes Sharks focused on an intermediate position between the sea and the shore, which in your work became a metaphor for the difference of the modern world, especially the topic of ecology. Tell us more about this.

MJ: With this piece, I explored the space between the sea and the shore. For me, it is a metaphor for the constantly changing world, which includes political, sociological and ecological phenomena. After a couple of years, the work takes on new contexts: the constantly moving coastal area reminds us of the world flooded by the pandemic; the brutal Russian occupation of Ukraine. We live between floods and low tides. My goal was to find ways to survive, to calm down, seeing how much drama is happening around me. I imagined that I was standing on the shore, watching the approaching tsunami; but then I turned my gaze to the unfolding beauty that helped me forget.

The installation space was divided into horizontal and vertical elements. The main vertical was the lighthouse, which supports the surrounding horizon like a backbone. I tied a lot of nets, for which I have received some criticism, as nets are a symbol of fishing, or anti-ecology. For me, though, they act as protection, holding and connecting wandering bodies, and also like pixels, dividing space and helping to see the details. I was interested in the different characters typical of the coastal area: a seal that washed ashore and then returned to the water after growing fins; an octopus that looks like an alien but is admired for its intelligence; women from Jeju Island in South Korea who dive without any aids, blending in with their surroundings, and in this way supporting their families. It was important to me that this work should not be a decoration, but an enchanting and interesting space into which you simply enter and exist, and forget reality. And even though that tsunami is approaching, you still manage to survive in its background.

I realised it was working when a woman asked if she could breastfeed inside the installation, and sat next to the seal skeleton. In that way, she went from being a viewer observing the environment vertically to being a horizontal one that involves the environment.

AS: In your thesis, you wrote about the desire to provide a space for joyful discoveries, a calm respite from the chaotic world, while still aiming to maintain vigilance and attentiveness. And now you mentioned the approaching tsunami: people usually panic or hide during such a disaster. Meanwhile, you try to stop this panic with your work: we know that a tsunami is approaching, but we are invited to escape from reality, at least for a while. How did the desire arise to provide a shelter with your work, rather than invite to a protest?

MJ: This is my escapist tactic. When watching the world, the news is often filled with helplessness. I no longer know what is true, and the flow of information is difficult to regulate. I think there are practical actions that each of us must do or not do in order to manage to live together and postpone the apocalypse; and at the same time there are abstract ideas on how to survive and calm down in the present. Sustainability is emphasised strongly in art and design, but it is equally important to achieve emotional harmony in order to function. The search for peace is my personal need, but I feel it is relevant for everyone. Maybe I have more capacity to operate in the emotional realm. It’s easier for me to create from abstraction, from intermediate states.

Morta Jonynaitė, ‘Skersiniai’, exhibition view, Verpėjos, 2021, photo: Lukas Mykolaitis

Morta Jonynaitė, ‘Skersiniai’, exhibition view, Verpėjos, 2021, photo: Morta Jonynaitė

AS: Last year, your first solo exhibition ‘Skersiniai’ opened: in the summer of 2021, visitors who came to the gallery in Marcinkonys railway station could become entangled in the webs you made. You created the works while participating in the ‘Verpėjos’ artistic residency. What motifs reflecting life in Dzūkija did you weave into the works?

MJ: Dzūkija and the residence were a kind of mini-world, a mythological reality, into which I briefly entered. I got to know the locals and the newcomers who came there to live. I realised that the saying ‘Were it not for the mushrooms and berries, the girls of Dzūkija would go unclothed’ is not a joke, but a saying that reflects the reality and the poverty. It is easy to romanticise this land. There is definitely something magical about it, but after staying for a while you also see the problems. Walking through the forests, I was surprised at how many clearings there are, and how life is supported by mycelium and spiders spinning their webs. This is a border area of Lithuania, at that time the refugee crisis was just beginning, which was felt by the locals. Despite all that, there are important people, like Onute Grigaitė and Laura Garbštienė, who, while living in their villages, like hyphae, weave a community network.

AS: How did the exhibition go in Marcinkonys railway station? Did the unusual space pose any challenges?

MJ: This railway station is the final stop, the trains go no further; therefore, the exhibitions are visited more by casual passers-by. It is an architecturally intense space, and my work is usually soft and barely visible, but that contrast was perhaps just what was needed. It was important for me to create a space where visitors, entangled in networks, would stop and take a look, and where the stories of the place and the visitors could be woven together.

AS: Artistic residencies usually have a set time-frame, during which artistic output is expected. Do you like this kind of timed approach to the creative process?

MJ: Before going on the residency, I already had a goal. I knew what I wanted to research, and that I would present the results in an exhibition. Such a complete escape to a new space was necessary; it was a luxury for me, when I could devote myself fully to creativity. The time limit partly helps to stay on the ball. I honestly thought that I would wander more in the woods, but I walked the least of all the months in that year. Nevertheless, the energy of the place was very inspiring; it was good to live there.

AS: In your work, one can feel a slow and conscious presence, reflections on the fashion industry, and at the same time a search for alternatives to consumption and a fast life.

MJ: I would like to distinguish between the fashion industry, which is constantly being demonised and belittled, and clothing as a medium close to every person. Designers face a lot of challenges: they have to take into account how much pollution they generate and how it affects bodies; and at the same time clothes can convey their story in a very direct way, creating a personal connection. It is more difficult for them than for artists whose activities are considered more elite; and yet no one asks whether another painting is needed. At the same time, both spheres are closely related. What you wear is part of the artistic process: you create character, clothes might become a form of expression. What I wear is important to me as well, it can give me more strength and self-confidence. It was interesting to read the recently published book What Artists Wear by Charlie Porter, in which the author studied the relationships between different artists and clothes, and their influence over their work.

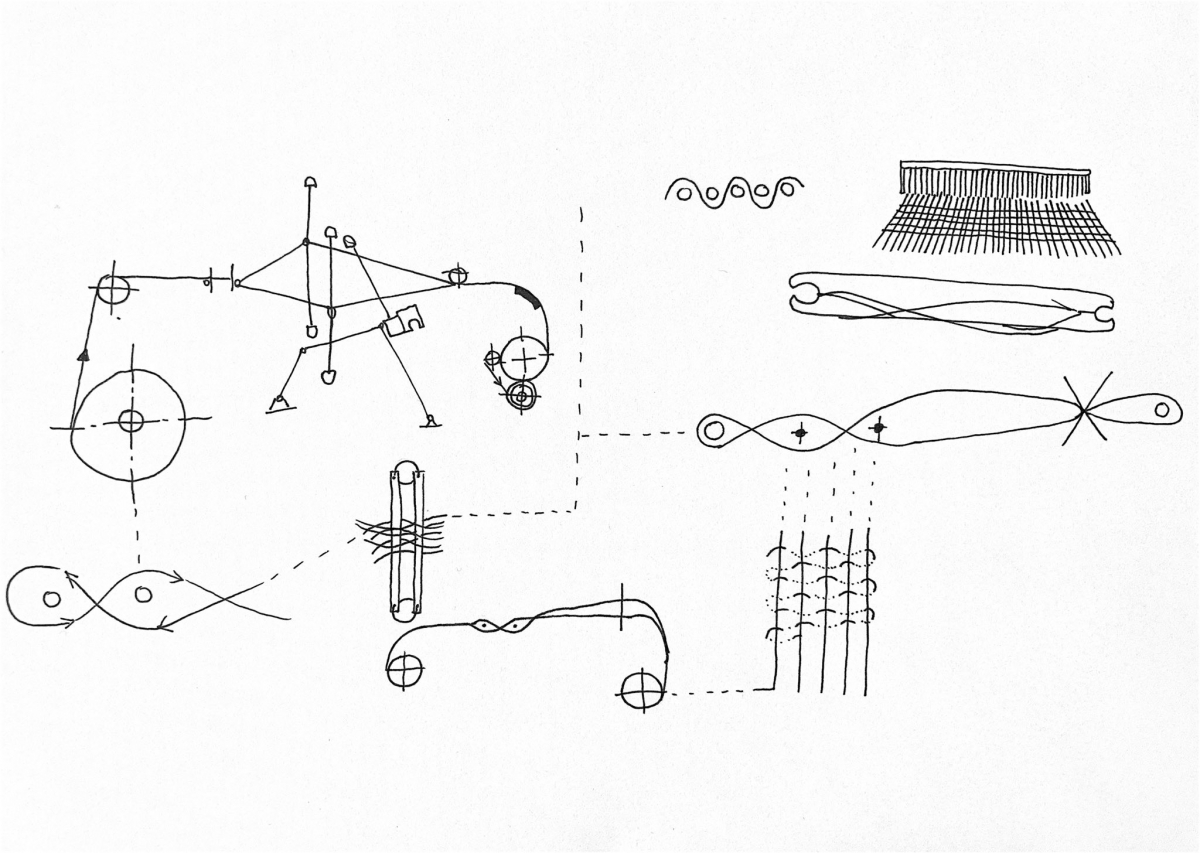

Weaving language, scheme by Morta Jonynaitė

AS: Your interest in fashion is also seen in your podcast ‘Capwalk’. Tell us more about it.

MJ: I have been interested in fashion since I was a teenager. I dreamt of being a designer. In order to get closer to that world, I worked as a model for some time. I thought I would study fashion design, but I discovered textiles, which explores garments much more closely. I am still looking for interesting designers with a unique vision, who offer an alternative to the banality of the industry. I think it is important to share such artists’ creations, because it can change our habits and attitudes towards clothes as consumers. I hosted shows at Palanga Street Radio, a community radio station. I received a very warm welcome there. I am grateful to them for the opportunity. I hope there were listeners who heard something meaningful.

AS: Creative life is sometimes inseparable from personal experience, so let us talk a bit about it. After finishing school in Vilnius, you decided to spend some time in Iceland. What impressions did you bring back from there?

MJ: After leaving a Catholic school, I knew that before studying I wanted freedom and escape for a while. In Iceland, I got what I wanted from nature, and that strong wind that blows through the brain. Life there was very intense. I experienced all the seasons, from total darkness to endless daytime. I participated in film festivals and concerts, and danced a lot. Various art events were held, where many people gathered. I was impressed by the Icelandic community: they are like one big family, and always support each other.

AS: How did you make the decision to return to Vilnius from the Netherlands?

MJ: I finished my studies when lockdown started, so I had only two choices: to return immediately, or to stay. For a long time, I maintained a long-distance relationship, so it was not difficult to make a decision. I wanted to return to my loved one in Lithuania. Living abroad is not easy, you need to put a lot of effort into it in order to adapt, both in domestic situations and creative practice. Everything is simple and clear in Lithuania: I know how different structures and groups work, so I can easily get involved in existing processes, or create my own operating model. It is also easier to combine personal practice and work here.

AS: What do your days and creative routines consist of?

MJ: For the last three months I have been working in film production, in the costume department. The days are long and precisely planned, but filled with various experiences. People on set become a temporary family, sharing their stories, laughter and struggles. I looked after the costumes of the actors in the crowd scenes, and since it was a foreign production, different types of actors were needed, including many foreigners living in Lithuania. I was curious about what they do, how they feel about living here, and I tried to form a connection with them. Now, after being in the company of so many people, I have reoriented myself to the stage of solitude, and being in my studio. This is my comfort zone and tranquility, where I shape the day by myself. I am happy to be able to create every day.

AS: Tell us about your creative inspiration. Is it people, books or processes, or perhaps a combination of these?

MJ: Stories inspire me most. I look for a balance between reality and fiction. I watch a lot of films, and then even more interviews with directors and actors. It is especially interesting how creators present themselves in public, films or Q&A. For example, I constantly follow the life of Robert Pattinson and his new roles. Having the image of a girls’ favourite, he keeps trying to hide this with independent film directors, to recreate the reality that has already become a constant in everyone’s consciousness. I’ve lately been immersed in Elena Ferrante’s books. She creates a deep, multi-layered world with such simple sentences. In the same way, I collect everyday stories. When I worked on the movie set, I carefully collected stories from everyone who came to be dressed.

AS: What creative adventures await you in the future?

MJ: This October my personal exhibition will open at Galera in Užupis. I am excited to attend the FITE (International Festival of Extraordinary Textiles) textile biennale in France this autumn as well. Now I have earned the creative luxury to prepare for autumn shows.

Preparing the warp. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė

Roni and Ronny. Photo: Morta Jonynaitė