Dreams are the ultimate escape from the banalities of life. Sweet dreams emerge as the opposite of the bitter nightmares of reality. Time and time again, the unknowns in the equation of life are filled in by dreams, visions and forebodings. But not everyone sleeps with closed eyes. The group exhibition ‘Sweet Dreams Foundation’ at the Nida Art Colony explores the transitory state that our world seems to be stuck in. Nothing is more permanent than temporariness, so artists try to rise above the brutality of war by connecting with the unfolding present.

Rethinking the relationship between reality and other mental states (without rejecting the view that reality itself can also be a kind of state), exhibition spaces seem to be closest to the dreamworld. The musical background of the exhibition (I’m waiting 4 U by Dizzy Davis, featured in Marta Margnetti’s piece) elevates the spirit of this art show into an ethereal realm. Julee Cruise-like music floats through the room and allows visitors to experience the transitional state between wakefulness and sleep. Quite a few works in this exhibition are therapeutic attempts by artists to find a safe place. Daniela Palimariu displays glazed ceramic pieces from the series ‘Hiding Solutions’. We can assume that this sleek-looking object can contain metaphysical matter and deliver us from the evils of the real world. The need for a different reality is expressed in Dasha Chechushkova’s ‘Seeing Water in a Room Foretells Change’. Her underwater world creates a childlike wonder and feeling of solace, perhaps symbolising retreat back into the womb.

It is a common strategy in wildlife to scare away attacking predators by making yourself appear bigger. Dasha creates a very large shirt, as if illustrating the legend of the giantess Neringa in her piece Mara, the Spectre of a Fox. Unlike the huge garments created by the American artist Kate Hamilton, Dasha’s shirt is made out of many different fabrics, so this piece allows onlookers to daydream about locals making clothes for their protective giantess

Natasha Kushnir creates an entire dream shelter in her installation The Place of the Unknown. According to the artist, it is the space of the person who appeared or disappeared in the woods. In a sense, it is a modern rendering of the book Walden; or, Life in the Woods by the transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The author formulated his arguments for civil disobedience motivated in part by his disgust with slavery and the Mexican-American War. The personal declaration of independence, the rejection of the world and all its injustices, and the need for spiritual awakening, are as relatable as ever.

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

The group environment is a contrast with the absolute solitude of the forest. Mila Kostiana invites visitors to participate in a group effort embroidering dreams in her piece Roots. It creates a map of a collective dream dimension, similar to how Howard Phillips Lovecraft’s collection of short stories The Dream Cycle depicts a dreamworld that even has its own map. Dream cartography was also practised by the Australian aborigines, who also had a dream-telling tradition: every morning, people sat down and shared their dream experiences. If one did not remember their dream that morning, they had to share two more the next day. Why can the work of the unconscious not be treated in the same way as any other currency of cultural exchange? It is interesting to note how patterns coming from the subconscious connect the modern visitor to the exhibition with traditional folk embroidery traditions: we do not embroider robots or smartphones, but choose to express ourselves through archetypal motifs of suns, waves and flowers.

In dreams, not only do we undergo a variety of surreal scenarios, but we can also try out completely different identities, as if they were masks. No wonder ancient peoples believed that humans bear within them a kind of duplicate, a ghost-soul that is able to leave the body temporarily and wander about during sleep. On closer inspection, the wearable sculptures-masks by Yana Bachynska do not seem to be made for concealment, but actually draw extra attention to the one who dares to wear them. We may not necessarily see our conscious selves in these masks, but eventually every mask becomes an emblem of the true self we desire to be.

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

While dreaming, you can meet all kinds of magical creatures: some might elicit fear, others might comfort you. Dog with Bone (Finder), Dog with Trumpet (Observer), Birds (Whispers) and Dolphin (Acrobat) by Christian Raduta seem to be in a league of their own. Meanwhile, The Guardian Angel by Kseniia Shcherbakova appears to play with biblically accurate descriptions of angels which are considerably closer to the term ‘nightmare fuel’ than to Michelangelo’s cherubs. There is an irony in wishing that divine intervention could save a world plagued by the consequences of its own hubris and inaction. If something or someone scares us in our dreams, is it still us doing it to ourselves? How can our ego divide itself into beings who, out of themselves, produce entities of which we are not aware that they were inside us all this time? Our outward identity may differ from the person we truly are on the inside.

Dreamers know that only outward improvements to life are not enough to bring real change. The most important is inner work. Intuition allows for creative risk-taking, and that can instigate a new open dialogue between the artist and the public. By witnessing the reverse of a creative process in Borys Kashapov’s Charm, spectators realise that this ephemeral piece of art proves that the real essence of things cannot always be pinned down. In today’s digital era, something that vanishes with time when exposed to the elements can actually be indestructible in other ways. The fact that every time you revisit the exhibition you can see an ever-changing artwork also stimulates the imagination. The opposition to constant mass communication, information wars, false advertising and various deflections is complete silence, blackout, null. The finale phase is a blank space, a tabula rasa, not feared or avoided, but accepted and foreshadowed.

A nightmare can expand into waking life. The short documentary film Dioroma by Zoya Laktionova shows something that does not exist any more. Mariupol, the tenth-largest city in Ukraine, was almost completely destroyed after the Russian siege. A female voice in the video from 2018 attempts to remain positive: ‘I’m sort of trying not to take in all the bad stuff happening right now […] And I think: Oh, no-no, that isn’t about me, that won’t happen to me.’ This hits especially close to home, because the images on the screen portray a world much like our current one: the shore of the Sea of Azov might as well be the shore of Baltic Sea, and the peaceful Ukrainian voices interviewed are not so different to our own countrymen. Stay awake. Someone has to do the night watch.

Exhibition opening. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

At the exhibition’s opening, the curator Lesia Kulchynska mentioned that it was an unplanned coincidence, but all the pieces in the exhibition were made from recycled materials, just like dreams, in a sense, are regarded as brain waste disposal. Wherever we look today we see recycled imagery: remakes, reboots, re-imaginings and covers are seemingly outshining the original products. We appear to live in a constant loop of cultural references, where the new is always just the revamped and revived old. But without getting into Francis Fukuyama’s End of History pessimism, we can acknowledge that what we witness now is not a particular cultural phenomenon, unique to just our current times, but rather a recurring exploration of the past after crossing the threshold of a certain era. Just like dreams and phantasms, the imagination is sometimes considered to be a by-product of the human mind trying to process all information and experiences in order to improve brain function and free up memory.

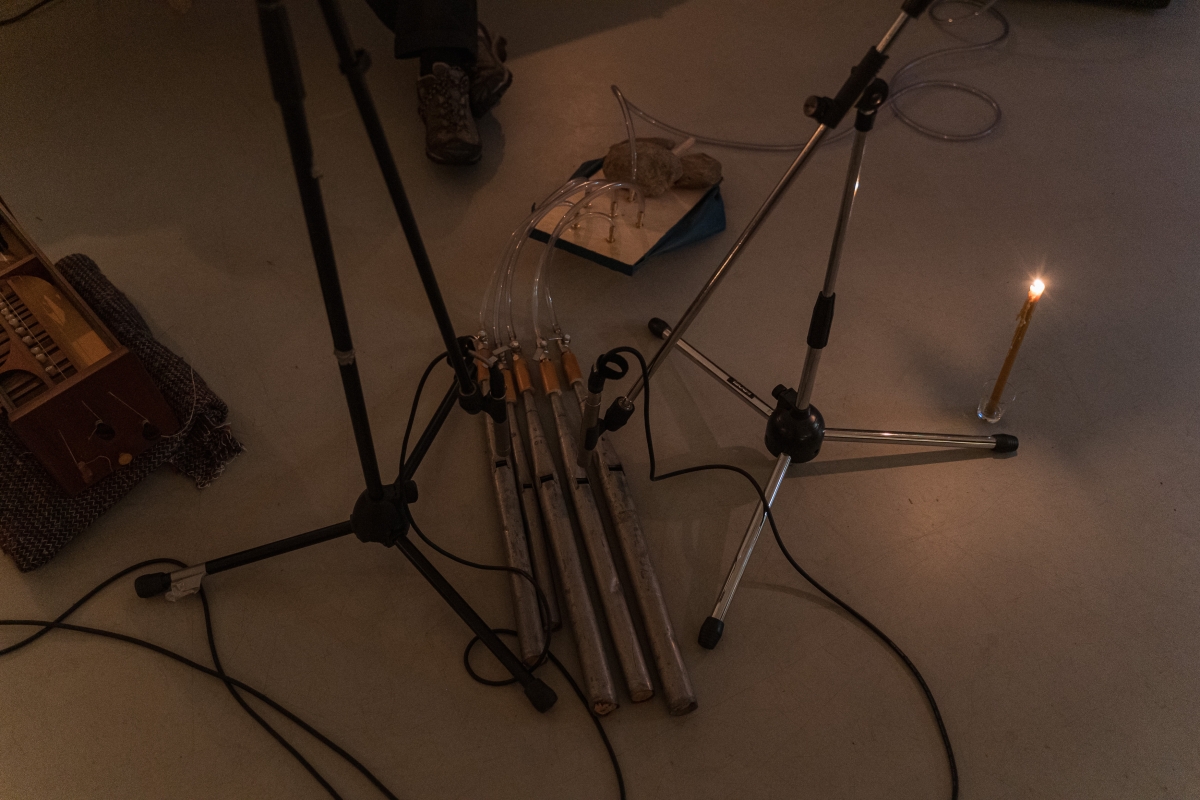

The opening of the exhibition ‘Sweet Dreams Foundation’ was accompanied by night service by 4444friends (Tatiana Chaikovskaya, Valentin Duduk, Anna Karanevskaya, Ilya Malafei), the ongoing and location changing performance ‘Wayward’ by Titilayo Adebayo, and sound performances by Sholto Dobie and viixii, which were visceral and moving. Titilayo uses movement as a tool for healing, heightening self-awareness, and finding the inner child. Their piece illustrates the saying ‘Not all those who wander are lost.’

Anastasia Sosunova’s site-specific sculpture My own Private Ghost Town (made in collaboration with Anton Shramkov) is a composition of pine boxes covered with sculpted concrete in the form of a modular bird house bastion. For the intended residents (swifts, starlings, bats, spiders, and their kin), this human-built housing is first of all the issue of trust; for others, like barn swallows and house martins, birds that now rarely use natural sites, it is just second nature. A reversal has occurred: people no longer adapt to nature, nature adapts to people. It is terrifying to see us humans impacting the physical environment to such an extent, although we still have hopes for a symbiotic coexistence with nature. Human altruism towards animals often comes from (environmental) guilt, a feeling that, not surprisingly, has a significant evolutionary purpose. Can we create something out of lack? A home out of feeling alienated? We are homesick for a place we have never even visited, and are always trying to recreate the world that was before us, hoping to undo the damage we have done, but ghosts still haunt us.

When you wake up, the dream does not immediately leave you. Just like after visiting an exhibition or seeing a performance, the further development of the works is left to the viewer. The horror and the bliss are equalised, the cry of a seagull flying over the Curonian Lagoon does not wake you up, but rather pulls you deeper into sleep, five more minutes, you reach hibernation without a predetermined end, an endless conversation between other sleeping consciousnesses ensues, no one notices that you are missing for months and months, maybe even a lifetime, but perhaps the strangest dreams are the ones you dream while still awake.

The group exhibition ‘Sweet Dreams Foundation’ is on at the Nida Art Colony (E.A. Jonušo St 3) until 16 October.

Photo reportage from the exhibition ‘Sweet Dreams Foundation’ at the Nida Art Colony

Anastasia Sosunova’s site-specific sculpture My own Private Ghost Town (made in collaboration with Anton Shramkov). Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition opening. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition opening. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Chicago Boys concert. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Exhibition view. Photo: Andrej Vasilenko