The newly rediscovered Latvian collection at Malmö Art Museum (Malmö Konstmuseum) contains 47 artworks that reflect the cultural identity and national romanticism of the time. It was donated to the museum in 1939, and was on permanent display until 1958. The exhibition ‘The Latvian Collection’ presents the original works, alongside eight new commissions by contemporary artists who have researched and expanded the collection. These new works explore themes of nationalism, nation-state building, and the fragility of smaller nations, while addressing the challenges of envisioning alternative organisational structures for nation-states in the face of contemporary geopolitical events. The newly commissioned pieces serve as extensions and interpretations of the original Latvian collection, and offer insights into its 2022 reception for future audiences. Curated by Inga Lāce and Lotte Løvholm, this exhibition ran from 2 December 2022 to 16 April 2023.

As visitors enter the exhibition, they were immediately greeted by the sculpture Metal Angel by the Lithuanian artist Anastasia Sosunova. This piece offers a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the ongoing ‘angelification’ of Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, where an estimated 300 angel statues have been placed in public spaces since 2004. These celestial figures have gradually transformed into a prevalent diplomatic offering from Lithuania, despite their tenuous connection to the nation’s inherent cultural symbolism. This intriguing parallel to the Latvian collection housed in Malmö Art Museum highlights the role of art as a diplomatic tool in crafting national narratives. As a result, the artificially constructed stories return to haunt us, manifesting as opposites of the angels they are meant to represent.

Anastasia Sosunova, “Metal Angel” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

The original works in the collection are presented in a refreshing and informative way, thanks to the innovative design by the exhibition architect Līva Kreislere. Particularly fascinating is the opportunity for viewers to examine the reverse sides of the canvases, revealing artists’ notes, dates, and other details that provide additional context. This unique display approach stimulates curiosity and a desire to delve deeper into the stories behind these works and the lives of their creators. The exhibition wall is thoughtfully designed to include a small window that piques the interest of visitors, revealing tantalising glimpses of the new commissions on display. This subtle design element not only draws visitors further into the exhibition, but also fosters a sense of anticipation and excitement.

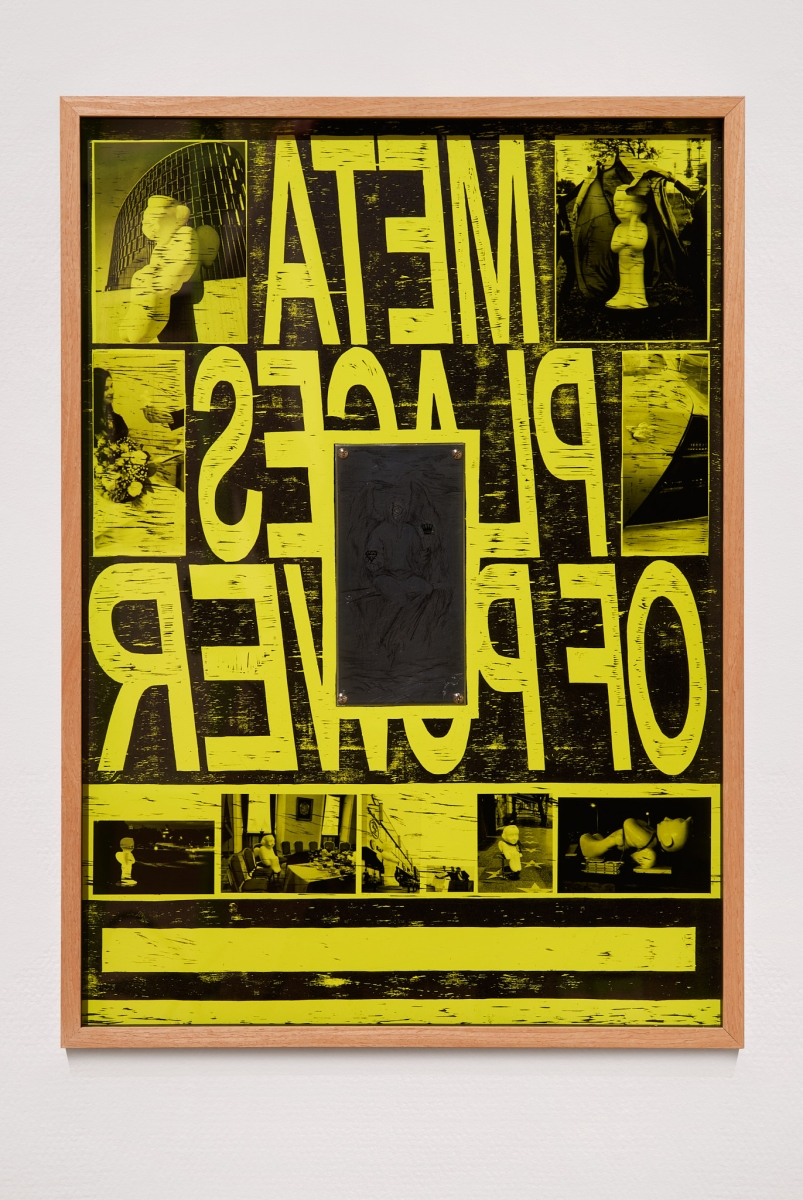

Anastasia Sosunova delves deeper into the theme of public angel sculptures in Vilnius with her collaged print Meta Icon. Drawing on the compositional logic of an icon, the piece underscores the concept of iconography as imagery imbued with agency. The prevalence of photographs featuring Vilnius’ angels, taken by tourists and locals, is evidenced by the numerous images Sosunova sourced from the Internet for her work. This phenomenon perpetuates a distorted representation of the city and its true cultural potential, favouring an ‘Instagram-friendly’ aesthetic over the authentic grittiness that would ultimately prove more genuine and sustainable in the long run. By highlighting this disconnect, Sosunova’s art invites viewers to question the impact of such insincere visual narratives on our perception of urban spaces and cultural identities.

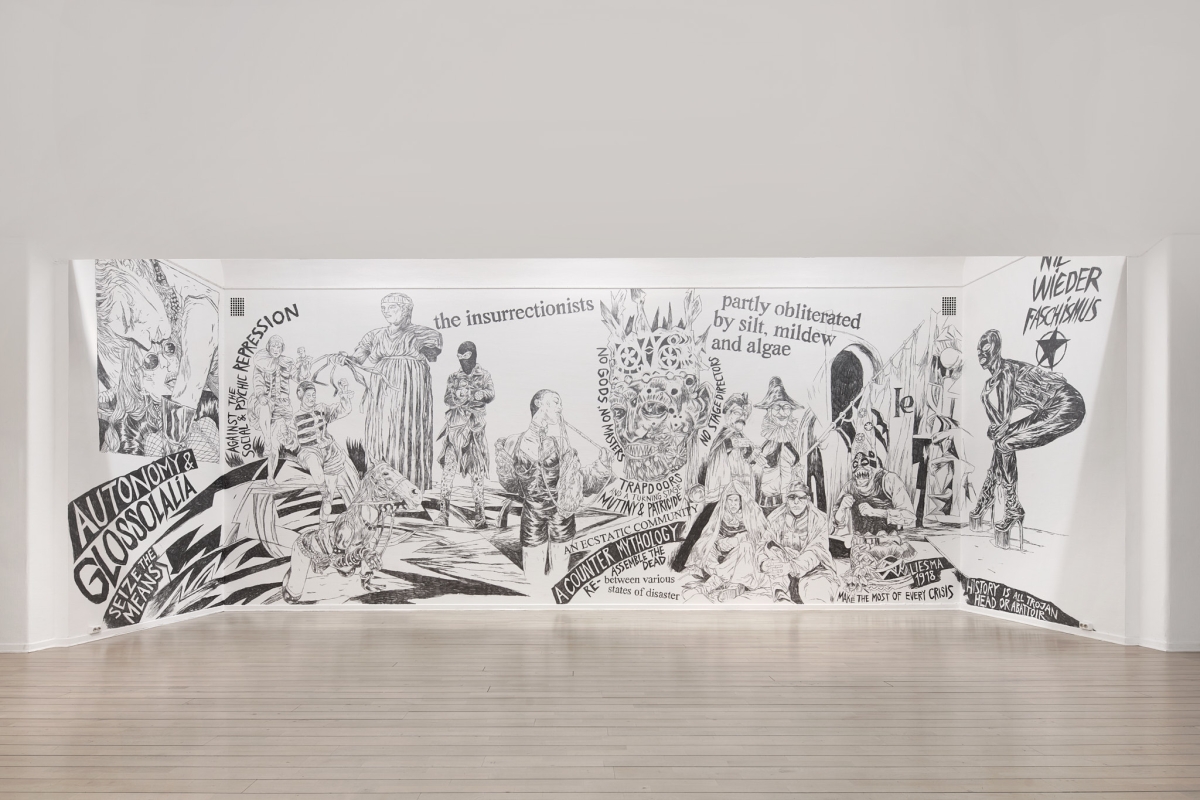

Makda Embaie’s sound piece If Joy was the Door, What would be the Room? takes its inspiration from Jānis Tīdemanis’ lively painting Carnival, and explores the concept of community building as an alternative to nation-state building. By focusing on the power of joy and human connections, Embaie’s work encourages us to consider the potential of grassroots movements in shaping society and fostering unity. Similarly, Asbjørn Skou’s monumental graphite drawing on the wall entitled Othertongue (sketch for an anarchist cabaret) serves as a diagram-like visualisation of the alternate futures and histories of anarchist movements that emerged in the tumultuous early 20th century on Latvian territory. Both Embaie’s and Skou’s works offer intriguing perspectives on the various ways in which individuals and communities can come together to resist and reshape dominant political narratives. Together, these two distinct artistic approaches encourage a more holistic understanding of nation-state building, exploring both the communal aspects and the political undercurrents that have contributed to the formation of modern Latvia. These works invite visitors to engage in a thoughtful examination of the various forces at play in the development of national identity and the ongoing process of self-definition.

Makda Embaie “If Joy Was the Door, What Would Be the Room?” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Lada Nakonechna, “Personal Relevant Collection” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

The Ukrainian artist Lada Nakonechna, in her thought-provoking installation Personal Relevant Collection, explores the unintentional universality of the works featured in the Latvian collection. She demonstrates that the personal expressions of the exhibited artists, despite their ostensibly unique cultural contexts, possess a certain resonance that transcends national boundaries, and could be reinterpreted to represent other nation-states as well. The Estonian artist Jaanus Samma’s wool rug entitled Brooch draws its inspiration from Jānis Kuga’s painting Sketch for stage design of Pūt, Vējiņi! (Blow, Wind!). The intricate figures adorning the rug represent characters from the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg (Kalev’s Son), a seminal work of Estonian literature that weaves together myth, folklore and history to tell the story of a legendary hero. Samma’s Brooch rug serves as a visually captivating and culturally rich exploration of the interplay between art, national identity and shared narratives. By combining elements from both the Latvian and Estonian artistic traditions, Samma’s work not only pays homage to the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, but also highlights the connections that bind these two nations together. In her installation A Snake is a Way: Unraveled Eternity is still Forever, Ieva Kraule-Kūna weaves a poignant tale of resilience and rebirth. Set in the aftermath of an unspecified cataclysm that has devastated the world, the narrative follows a mother and her child as they embark on a journey to rebuild their lives amid the ruins of a shattered civilisation. It also invites viewers to reflect on the cyclical nature of history and the potential for renewal that can emerge from even the most catastrophic events. Although each piece is unique in its artistic approach and subject matter, they collectively illuminate the complexity of human experience, transcending cultural and national boundaries to reveal the threads that connect us all.

The video installation Collection by Ieva Epnere presents a unique reinterpretation of the Latvian collection’s narrative by employing a series of choreographed scenes set against the backdrop of the sea. Symbolically, individuals are shown holding blank canvases, which share the same dimensions as the works in the collection, suggesting the potential for new interpretations and connections to be made. The audio component of the installation features voices enunciating the names of Latvian artists and the titles of their works. This chorus of voices intermingles with the sound of the sea’s waves, reflecting the myriad cultural endeavours that strive to create connections and foster understanding. However, despite these efforts, a layer of misunderstanding inevitably persists, adding an element of complexity and tension to the piece. Epnere’s use of the sea as a central motif evokes notions of fluidity, change and the passage of time, all of which are intrinsic to the process of interpreting and reinterpreting the Latvian collection. The ebb and flow of the tide symbolise the constant evolution of our understanding of the works and the cultural context in which they were created, as well as the shifting dynamics of artistic expression and reception.

Ieva Epnere, “Collection” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

The video installation Collection also incorporates an element of danger and tension, as the spectator may experience apprehension concerning the safety of the artists’ avatars and their paintings. With the sea as the backdrop, it presents the possibility that the waves could engulf them at any moment. This sense of peril adds another layer of complexity to the piece, emphasising the vulnerability and fragility of art, its creators, and their legacies. This fear of loss alludes to the challenges faced by the Latvian artistic community throughout history, as it struggled to preserve and transmit its cultural heritage in turbulent times. The ever-present threat of the sea swallowing the avatars serves as a metaphor for the potential disappearance of these artistic expressions and the erasure of their significance in the face of adversity. By incorporating this element of danger, Epnere challenges viewers to reflect on their own role in preserving and celebrating the Latvian collection and the wider artistic heritage. It serves as a reminder of the responsibility each individual bears in safeguarding the creative expressions of the past, and ensuring their continued relevance and appreciation for future generations.

Perhaps the most emotionally charged, incredibly nuanced piece analysing a very complicated, haunting and tragic period in Latvian (and European) history is the installation Trenches by Susanna Jablonski and Santiago Mostyn. It features two curving, suspended textile sculptures portraying idyllic scenes from postcards exchanged in Liepaja at the time when the mass extermination of the city’s Jewish population occurred. It serves as a striking reminder of the contrast between the seemingly serene visuals on the postcards and the unspeakable horrors that unfolded concurrently in the very same locations. The film Umdrehen (Turn Around, or Reverse, in English) contrasts audio from the 1981 testimony of a German naval officer, Reinhard Wiener, who partially documented the mass killing of the Jewish inhabitants of Liepaja in the summer of 1941, with footage captured by Jablonski and Mostyn at the massacre site in 2021. By incorporating Wiener’s testimony and their own footage from the massacre site, the artists reveal compellingly the lingering echoes of pain and loss in the physical landscape. This sensitive treatment of a delicate subject is reminiscent of James Benning’s documentary Landscape Suicide which opts not to focus on the killers themselves but rather incorporates the director’s signature contemplations of the landscape. Similar to Benning’s documentary, Jablonski and Mostyn’s installation offers an alternative perspective on the atrocities committed during this dark chapter of Latvian history. Instead of placing the emphasis on the perpetrators, the artists focus on the land itself, inviting the viewers to reflect on the role of the environment as both witness and silent accomplice. Through this evocative approach, Trenches not only serves as a testament to the lasting impact of such tragic events on the human psyche, but also as a call to engage with the past in order to understand and heal from its consequences. In doing so, the installation transcends the boundaries of art and history, creating a deeply resonant experience that invites introspection, empathy, and ultimately, hope.

Susanna Jablonski and Santiago Mostyn, “Trenches” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

The film not only delves into the historical context but also addresses the universal themes of the perceived pseudo objectivity of camera media and the actual subjectivity of physical reality. Wiener’s statement ‘I want to stress that I couldn’t see clearly what was happening around me while I was filming because I was looking through the lens and therefore could only view part of the scene’ highlights the limitations of camera media in capturing the full extent of events. The installation features the actual type of camera used by Wiener, a Cine Kodak Eight Model 60 camera, which moves automatically as if operated by invisible hands. This inclusion serves as a commentary on voyeurism and depersonalised guilt, as the camera’s limited perspective and mechanical nature can contribute to detachment from the horrors being documented. By incorporating the camera as an element in the installation, Jablonski and Mostyn invite viewers to consider the complexities of documenting and perceiving reality. They encourage an exploration of the interplay between the observer and the observed, as well as the role of technology in mediating our understanding of historical events. The artists subtly question the reliability of recorded media, and urge the audience to confront the biases and limitations inherent in such documentation. Furthermore, the film’s focus on the camera’s subjectivity underscores the importance of revisiting and reevaluating historical accounts to gain a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the past. It serves as a reminder that our perception of history is often filtered through the lenses of those who documented it, and that a more empathetic and critical approach is necessary to truly grasp the magnitude of the events and their impact on humanity.

The video piece masterfully evokes a range of emotions, prompting viewers to empathise not only with the victims but also with the witnessing cameraman. Through its exploration of the complexities of human experience, the film captures the cameraman’s trauma, powerlessness, and, intriguingly, his innocence. This nuanced portrayal of the individual behind the lens invites the audience to consider the moral and emotional toll that documenting such harrowing events can have on a person. By humanising the cameraman and highlighting his emotional struggle, the artists encourage viewers to reflect on the psychological impact of bearing witness to atrocities. The film demonstrates that the pain and suffering of the victims extend beyond their immediate experience, affecting those who document and observe these events as well. This expanded perspective fosters a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of human experiences and the shared burden of collective trauma. Moreover, the portrayal of the cameraman’s innocence, despite his proximity to the events, raises urgent questions about the nature of guilt, complicity and responsibility. The film challenges the audience to consider the complexities of moral judgment and the extent to which individuals can be held accountable for their actions or inaction in the face of such atrocities. By capturing these multifaceted emotions, the video piece serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of empathy and compassion when engaging with historical events. Through its exploration of the human experience in all its complexity, the film encourages viewers to recognise and honour the diverse perspectives and emotions that shape our understanding of the past, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and empathetic approach to history.

Asbjørn Skou, “Othertongue (sketch for an anarchist cabaret)” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Ieva Kraule-Kūna, “A Snake Is a Way: Unraveled Eternity Is Still Forever” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

The emotional toll of engaging with dark and harrowing historical events is often underestimated, as is demonstrated by the tragic story of the Chinese American journalist and author Iris Chang. Known for her best-selling book The Rape of Nanking, Chang later researched the brutal Bataan Death March, which led to a diagnosis of reactive psychosis and ultimately her death by suicide. This highlights the importance of recognising and addressing the psychological consequences of confronting difficult history. As is demonstrated by the majority of new commissions (which now also belong to the Latvian collection owned by Malmö Art Museum), their creators have successfully navigated the challenge of presenting complex narratives in a sensitive and inspirational manner, while acknowledging the emotional and psychological intricacies involved. These works explore the impact of historical trauma on artists and audiences, encouraging viewers to approach history with empathy, understanding, and respect for the challenges faced by those dedicated to preserving and sharing the stories of the past.

The curator Lotte Løvholm mentioned that working with this collection was like a healing process for her because of her own Latvian heritage. As a testament to the power of art as a means of healing, understanding and reconciliation, the exhibition not only provides a platform for exploring complex and sometimes painful histories, but also fosters a deeper connection between individuals, communities and the past. In doing so, it becomes a space where healing can be achieved on multiple levels, promoting a greater appreciation of the human experience and the enduring resilience of the human spirit. It will undoubtedly be fascinating to observe how the exhibition is received by the Latvian public when it is displayed in Riga, as plans are currently under way for this. Such an exhibition in the heart of Latvia is bound to evoke a wide range of new and diverse interpretations, sparking thoughtful dialogue and further enriching the discourse surrounding the collection and its cultural significance.

Exhibition “The Latvian Collection” at the Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Exhibition “The Latvian Collection” at the Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Asbjørn Skou, “Othertongue (sketch for an anarchist cabaret)” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Asbjørn Skou, “Othertongue (sketch for an anarchist cabaret)” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Exhibition “The Latvian Collection” at the Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Jaanus Samma “Brooch” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Lada Nakonechna, “Personal Relevant Collection” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Anastasia Sosunova, “Meta Icon” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc

Makda Embaie “If Joy Was the Door, What Would Be the Room?” 2022, Malmö Art Museum, 2023. Photo: graysc