Life is not all lovely thorns and singing vultures, says Morticia*, while cutting the rose blossoms off and arranging their naked stems in a crystalline vase with no water. Then she dips her fingers in between the thorns, and awes.

In the sixties, she was an exotic stranger flirting with death, caring for monstrous plants in the orangery of her castle. Flesh-eating flower named Cleopatra was a loyal companion she enjoyed feeding. The black hobble dress she wore was so narrow it impeded her stride, making her body flutter as she danced in the frightful parlor, where every soul was welcome.

Horrible dreams caused by poisonous plants were Morticia’s favourite, leaving a ghostly glow around the eyes. In the Middle Ages these dangerous flowers were vital ingredients in love potions, concoctions and magic salves. Thus, continuing the rituals of her ancestors, she generously treated her guests with these steamy mixtures. She was so sweet even a polar-bear skin rug named Bruno was soothed by her low and subtle voice. But she was instantly taken aback when one went astray and did something “pleasant.” She saw beauty in the grotesque, she was difficult for the ordinary to fathom, her smile was deadly and darkness suited her so well they became synonymous. But as her alien image flooded the mainstream, at the new millenium her exoticism turned to gas and we started looking for new spooky neighbors to be intrigued by.

Tzvetnik is an online art flower garden, founded in 2016, and managed by philosopher Natalya Serkova and artist Vitaly Bezpalov. It is a growing collection of photo documentations of art shows, interviews and texts.

Vitaly Bezpalov & Natalya Serkova

Aistė Marija Stankevičiūtė (AMS): I’d start the conversation from features. As soon as I open the Tzvetnik page, sharp visual codes catch my eye: objects that are more likely to be seen on the shady street than in a typical exhibition space; edgy sneakers worn for too long; wreckage from around the corner. You tend to show things unpolished, sometimes even emphasizing their uncleanliness. How do you choose exhibitions? The pieces seem so carefully selected I naturally want to ask: what curatorial rituals do you go through when choosing what to add to the collection?

Tzvetnik: There is a curious point to be made here. On one hand, it is difficult to argue with the viewpoint that the art we publish might adhere to a certain formal code (which your description corresponds to, among other things). On the other hand, we also publish projects that are difficult to fit into the visual frame that usually outlines ‘that art from tzvetnik’. And in between, it would be interesting to mention conceptual approaches, compared to formal ways of making art. Undoubtedly, conceptual approach influences the appearance of art, but this influence can manifest itself in very different ways, hence the difficulty in delineating the formal framework. From a conceptual, methodological point of view, we can distinguish the following points (each of them, to a greater or lesser extent, is reflected in the projects we select). First, this is art for which there is no longer a border beyond which the Internet ends (unlike post-internet art)—for these artists, the Internet is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. This is art that works with documentation as another of its features, rather than treating it as a disturbing but unavoidable shortcoming of its own display. This is art that welcomes all kinds of speculation, fakes, and generally different manipulative tools of mass culture making this all work for itself. Finally, this art exists in an infinitely lasting network (digital, conceptual, formal, narrative…) and includes this infinity in itself: anything can be part of it. If we feel that the above qualities are intrinsic to the project, we publish it, despite possible flaws and rough edges.

AMS: You mentioned art with no outline of where the Internet ends, it seems to me that, within the Internet itself, no matter where it takes place, there is a certain algorithm of how the images circulate. On social media platforms the exhibition photo-documentations are caught in the same net along with selfies, odd objects and fashion brands – one image determines how we see another popping-up after it. Epoxy sculptures scroll after five-headed cats, Balenciaga jackets, exhibition views and carefully post-processed skin. It seems only logical, that the rough edges of physical shows soften too, becoming as blurred as a cheek of an Instagram influencer. You must be receiving a huge stream of exhibition views, have you noticed any change of art objects themselves, after the popularisation of art archiving platforms online? What mutations are they going through? How much do you think the visual codes that artists choose are influenced by objects that look like art on social media?

Tzvetnik: It is easy to see that one of the important visual codes of this art is the desire to highlight the material involved in work. We are never talking about cutting corners or flirting with the mass-media induced blur effect, (again, unlike in case of post-internet art). On the contrary, it is as if the artists are protesting against this, presenting broken, warped objects in which the material is jutting out in all directions and defiantly asserts itself. In fact, to define this as a protest against media images would be the simplest solution. It seems that there is a deeper reason why artists are so insistent on breaking and reassembling objects, creating inhuman monsters and trying to bring inanimate matter to life through various manipulations. The reason is that our generation has lost its very sense of the inner logic of the world. You write about a scrawl in which five-headed cats follow fashionable jackets and exhibition views—this mix makes it increasingly difficult to grasp clear cause-and-effect connections. And artists refuse to do this, instead it’s as if they’re trying to offer new logic instead. It is no longer so much a question of reacting to certain visual codes or online methods of showing art, as of trying to reassemble this world, to create something qualitatively different. This impulse has not been present in art for more than half a century, which is the whole period of time that contemporary art is considered to belong to. In this sense, the art we are dealing with and discussing now, turns out to be truly post-contemporary art.

Meme, unknown author

AMS: The notion of post-contemporary sounds intriguing – it makes contemporary art look so yesterday. It’s interesting to think about art “after today” as if that “today” is already over and we’re somehow observing what has already come after it. Could you break down this term for me and the readers?

Tzvetnik: As we understand it, the term post-contemporary as applied to art relates to several different aspects. One of them, of course, has to do with the proverbial here and now. Contemporary art has been trying to grasp this moment of now for 60 years, and all its conceptual and formal preconditions stemmed from this aspiration. It tried to decipher this moment, to explain something to the audience, to the community, to art history. It has often sought to make predictions or supposedly influence our future through roundtable discussions in museums, and in part because of this it has been firmly attached to the moment of the eternal present—that eternal capitalist present which lasts forever and promises no deliverance. And if contemporary art deciphered the present, then it must itself demand its own complete conceptual deciphering. Unexplained contemporary art is not yet art. It never burst into the thick of things and always maintained a critical distance from the world, a distance necessary for measured observation and note-taking. This slightly (or maybe not slightly at all) arrogant observation became a sort of a pad that let through not everything, but only things that were undeniably valuable for the utterance. Finally, another point concerned the relationship between art and exhibition space—no matter how much contemporary art criticized the white cube, it always needed it—to produce that very distance, a visual opposition to the world of non-art, to highlight the sifted material, to self-verify, to recognize itself as art. Contemporary art was and remains an elitist machine for the production of articulated meanings and colossal surplus value, and each part of the mechanism of such a machine must occupy its own, clearly assigned place.

Now let us look at what is happening to art today. Instead of articulate statements, we are offered a chaos of images, meanings, signs and words. Instead of the expected distance of art in relation to the world, it almost completely merges with the garbage of digital and physical spaces, spreading out in all directions across those very spaces. Instead of a white cube, there is often only a background on which the outlines of the work appear, just as the outlines of objects appear in a lit (not always well-lit) room. Play, mockery, infantilization, travesty, and buffoonery. All of this without the postmodern smirk of art, which only played games but never became a game in and of itself. The most confusing thing here is that the artists do all this with full seriousness and a responsible attitude to what is going on around them. The old ways of producing meanings are simply no longer satisfactory to any of us; they are insufficient, hierarchical and rigid. An important point here is the fundamental permeability of the structures that the new art is constructing today. These are mobile, omnivorous, porous structures that deny strict screening and distance. Exactly the same definitions have been given to capitalist structures for quite some time now, and it seems important to us that art today openly appropriates the dominant capitalist logic rather than attempting to criticize it through sophisticated reflection. This openness and honesty contains much more pure, explosive energy than the tired contemporary art of the post-contemporary world.

We want to emphasize the aforementioned permeability of structures. Meanings seep through these structures, but escape somewhere else without getting stuck in the grids. Thanks to this, the new art is no longer hostage to this eternal present, it can turn towards a new or old metaphysics, an individual mystical experience, a medieval mooch or a speculative future. Contemporary art also seeps through these structures—the distinction is not so obvious, the boundaries of distinction are fluid. But the distinction still needs to be made. People have been trying to use the notion of post-contemporary art since the late XXth century, but this notion has never really taken hold, probably because the logic of the production and reception of art has remained the same. Let’s see if the changes now taking place are sufficiently obvious and if the time has come for post-contemporary art to enter the scene according to its internal logic and external necessity, and not only at the whim of the professional community.

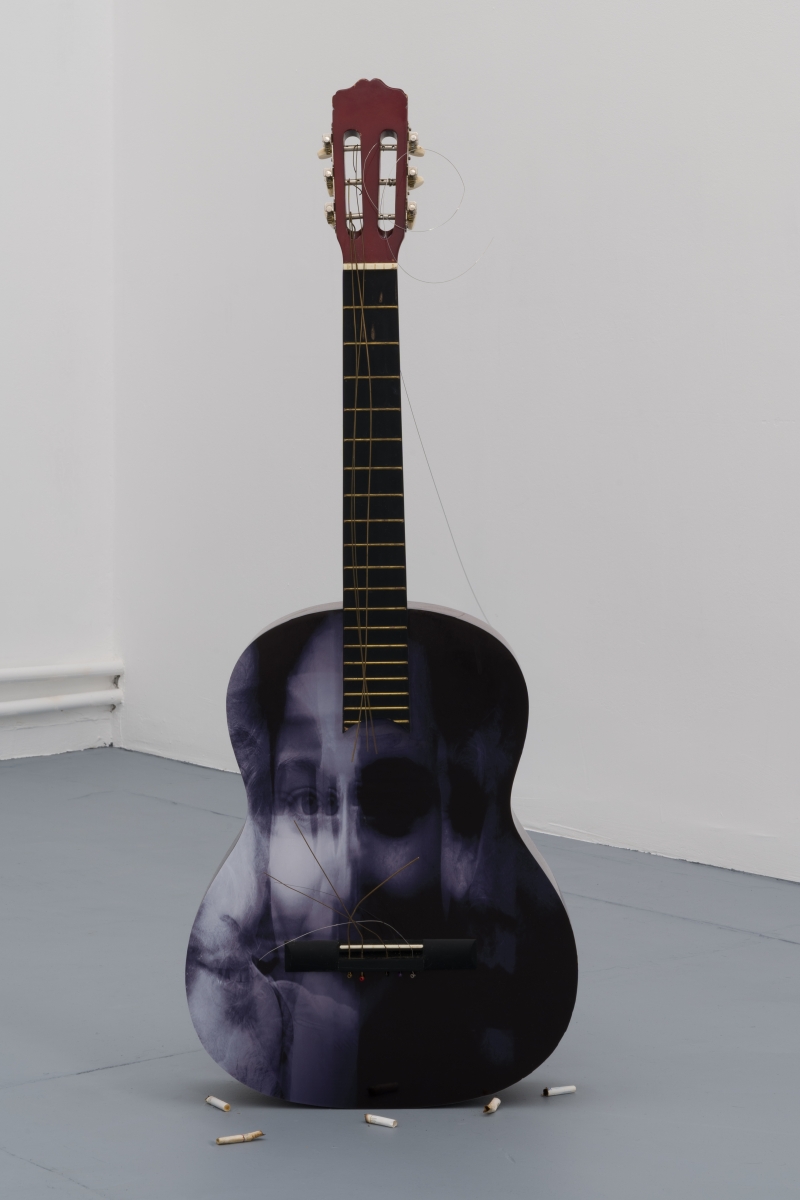

Vitaly Bezpalov, The Arch, 2021, fake photos, 1998-2005 drawings, drawings by Ilya Smirnov, newspaper clippings, bandages, medical masks, salami on wood, 250 x 120 x 10 cm, detail / Quintessence II at Plague Space, Krasnodar, installation view

AMS: Could post-contemporary art be called the art of the future? How does this future find its place among today’s things?

Tzvetnik: Paradoxically, this art is precisely the art of the present, but there is an important point here. If we resort to Christian discourse, contemporary art is the art of St. Augustine, one of the major figures of Western Christianity. For Augustine there was nothing but the moment of the present, the very here and now in which we all find ourselves today. Live that moment in the fullest, most responsible way possible (to God or to anyone else, that’s a secondary question for us) and you’ll be fine. Augustine cannot jump into the future simply because there is no future for him, only the everlasting now. Post-contemporary art is the art of Apostle Paul, who, by the way, being an apostle and having managed to get into the New Testament, had not even seen Christ in person—just as nothing prevents us today from discussing objects of art seeing them only from a monitor screen. For Apostle Paul, the moment of the present was just as important, only it was important precisely because it was a direct gateway into the future. The future (the Second Coming, according to Paul) can happen at any moment, it is already here, it just has to happen, and our present is separated from that future by a membrane so thin that it is impossible to grasp. This speculative, paradoxical juxtaposition of times seems to us to be the next step that art takes today. Post-contemporary art is one hundred percent the art of the present, but of the present which future has already arrived.

AMS:I really like your choice to explain art processes through such sacred figures. It would be interesting to know if there are any other creative forces, distant from artists and exhibition views, that intrigue you? Artists seem to be the main characters in both the text and the special sections of your page, I wonder, are there any other, hidden occurrences?

Tzvetnik: Art reveals itself to be blobs on the surface of the world, and it has always been interesting for us to observe not only the inner life of these blobs, but everything that shapes them, gives them look and meaning. Art is beautiful in its ability to have something to do with everything, and everything can potentially have something to do with art. In this sense, although we are professionally engaged in art, our lives are not limited to a particular area of specialization. Diverse and unexpected things can enter the orbit of our interest, from the design of rocket launchers to the history of the medieval plague or modern marketing technology. Today our interest is delineated by film theory and the specifics of horror movies, the history of mystical doctrines and contemporary metaphysics, political philosophy and communication theory, and an attempt to make sense of what goes on in the mind of a growing cat (a painful topic). Perhaps the most valuable thing that art can give you is the ability to think more broadly than usual, to look around vigorously, to remain a child and rejoice when a ladybug sits on your hand, but at that very moment to discuss the structure of the universe and to realize that you are working, not just taking a break from your usual routine. We are building TZVETNIK in order to have as many such moments in our lives as possible.

*Morticia, Addams Family.

This text is part of the Artnews.lt magazine issue on exhibition views and their distribution online, curated by Jogintė Bučinskaitė.