Angela Maasalu is a London-based Estonian artist whose solo exhibition ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’ was just on display at Tartu Art House.

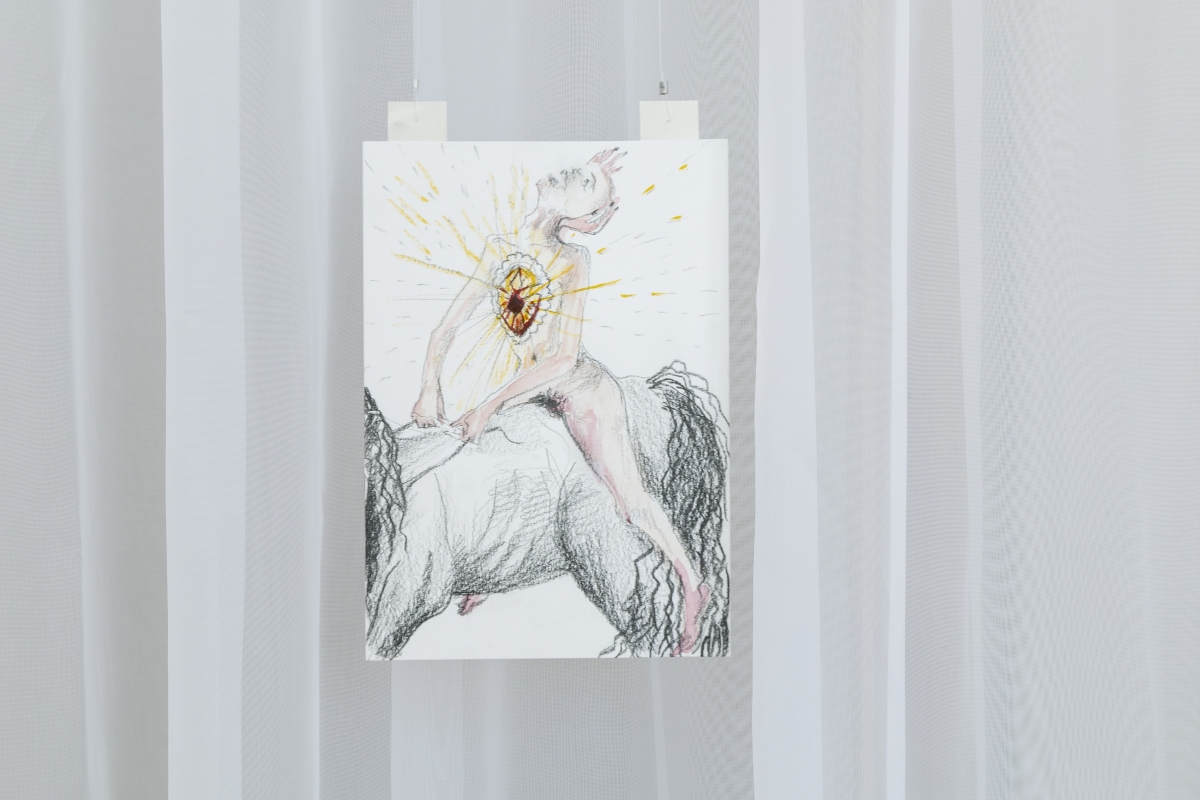

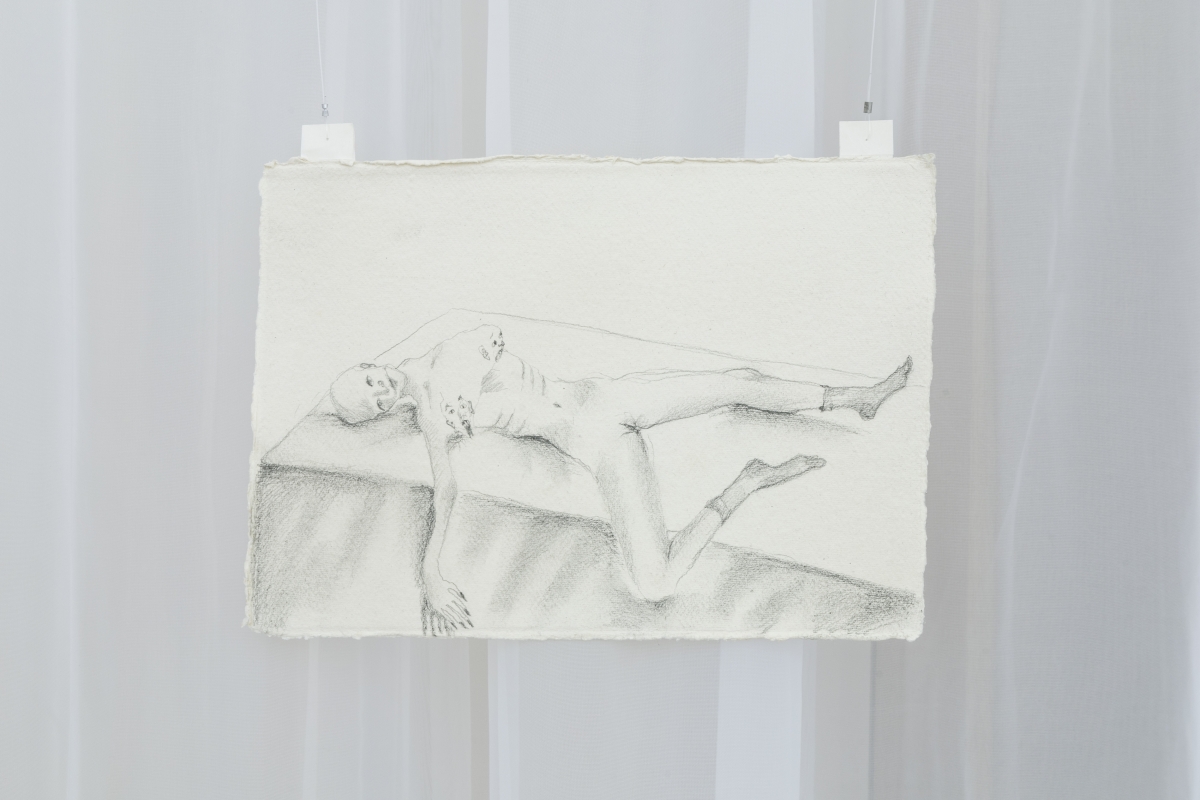

In the many chambers of Angela’s palace of fools live creatures that hide their faces behind masks; false tears trickling from the back of their heads, a fragile character stuck between the talons barely breathing, a woman floating, somewhere between melting and drowning, wading into the distance, a resigned body stretched out on a tennis court, a lion watching over sleepers, ghostly figures with a feverish glow, insubstantial contourless horizons, amphibian reptiles, monkeys, scorpions, and many others. Mutants that have stepped out of the canvas of life, and are now wandering around in the maze of the absurdity of the world. The characters in ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’ are perplexed by the surrounding world, apathetically gazing into the distant unknown. Contemplating individualistic behaviour, they feel trapped against the backdrop of decline. They are accompanied by the bitter smog of tragic misanthropes. Maasalu’s practice stems from autobiographical episodes, but she translates it into symbolic and poetic imagery in order to expand her personal experience to a more widely read and societal level.

After the hustle and bustle of the exhibition opening and Angela’s return to London, we sat down one night to reflect a bit more on her exhibition, and on her oeuvre in general.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

Maria Arusoo: How do you feel now that a few weeks have passed since the exhibition opening?

Angela Maasalu: Quite deflated, and very happy at the same time. I feel one gets this feeling of ‘now what?!?’ every time after the opening of a show or after finishing a project. Working on new paintings has helped.

MA: You studied in the Painting Department at the University of Tartu (2009-2012), and then in 2012-2015 you studied for your MA at the Estonian Academy of Art, after which you moved to London, where you are now based. How was your return to Tartu?

AM: Quite difficult, I must admit. While I was living there, I knew that I wanted to get out. I also dreamt of leaving Estonia quite early on, and, retrospectively, I think it was very important for my work to develop the way it has. But at the same time, having said that, there is also something very pleasant about doing what’s basically my biggest solo show to date in this particular place, like a nice summary of the past, say, twelve or thirteen years.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

MA: In your solo exhibition ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’ currently on display at the Tartu Art House you are showing twenty-seven paintings dating from 2020 to 2023. Can you give us an insight into the last three years? What themes and ideas were you interested in?

AM: I feel the theme for the show grew really naturally out of what I’ve been working on in the last few years. It’s been about moving forward, from perhaps more insular and diary-like perspectives to looking at how it all connects with the bigger picture. I think 2020 was also a perfect time to develop my practice, as I had more time to spend in the studio than I ever had before, so it started from there.

I’d say it’s about how we’re trying our best to function in society. When pretty much absolutely everything is the monetised celebration of individualism, our focus on personal growth and trying to look after ourselves and promising each other ‘next year will be our year’ etc, just doesn’t actually add up, and stuff is continuously generally more f****d, no matter how hard we try. Also, since the pandemic, like every time you open the news, there’s another WTF moment, like you can’t make this shit up. Then there is climate change, the cost of living crisis, the war. It’s an exhausting and bleak backdrop for any hopes and dreams. The fool with a heart of glass is trying to navigate it all as well as they can. It’s also about me, as well as being about everybody else. And the overall story is not all negative at all. I’d like to think there’s a lot of self-irony and humour in my work as well.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

MA: Clowns and jesters are subversive figures that are sources for potential (productive) humour and are sort of chameleons, moving and morphing between different contexts. Circus elements, masks and jokers have been present in your oeuvre for a while. Can you remember where it all started, and what meaning these images carry for you today?

AM: It started with an interest in the Pierrot as a character from pantomime. Him longing for the love of Columbine, who left him for Harlequin, making him this sad figure that many cultural movements later found amenable, the foe of idealism, a fellow sufferer, etc, and many authors and artists have used this theme. So I found it an interesting motif, which for me also represented various things. It could be pathetic, as well as evoking empathy, and in many ways I could identify with Pierrot.

MA: Literature and film have greatly influenced the current exhibition. You were reading Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism when you started working on the show; there is a direct reference to Werner Herzog’s 1976 film A Heart of Glass; and you have also mentioned Federico Fellini’s La strada. Can you elaborate on these references?

AM: Reading Berlant when I received the invitation to do the show at Tartu Art House was a pure coincidence, in a way, but it worked out perfectly, as I had already thought somewhat about these topics in my work, and then it just very naturally created the basis theme for the show. I guess it takes me back to one of your questions as well: moving forward to think about societal problems in general, and just not from my insular personal perspectives.

Werner Herzog’s A Heart of Glass is an incredible film. The sort of surreal madness of it is really disturbing in the best way possible, and then realising how relatable it all is with its references to the downfall of modern society.

I saw La Strada as a kid, and I remember feeling such intense emotions after it. I somehow immediately realised how the roles of Gelsomina, Zampanò ‘the strongman’, and Il Matto ‘the fool’ seemed to represent ways of living, or certain characters as a whole. It’s very literary and quite poetic, like Il Matto trying to persuade Gelsomina to appreciate her value and purpose in life, etc (but then she also goes and suggests marriage to the other brute [!], recognisable problematic patterns in life …). You basically hate Zampanò throughout the whole movie, but in the end you can’t help feeling compassion for him for suffering his own pain, hence the cruelty, and so on.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

MA: Your titles are really evocative: Bleeding Ears and Crocodile Tears, Colder than the Witch’s Tit, A Fool Crying over his Dead Monkey, Becoming a Lizard Human, etc, providing a rather strong narrative. How much do you want to preface your works through these titles?

AM: I think the titles often have a weird twist (deliberately), which can open them up to various interpretations. But sometimes it can also be super-direct. The paintings I end up liking the most are actually the ones where the title sort of shapes it from the beginning, like the work starts with words or text, then various layers emerge from that.

MA: In the exhibition ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’ you have created an amazing design for the space. Can you please tell us a bit more about the dramaturgy of the space, and how you want the space to contribute to the display of your works, and to provoke new ways of looking?

AM: I immediately knew I couldn’t just have paintings on walls and that’s it. Otherwise, I don’t think the theme would have come through at all. My work was once called ‘too theatrical’ by someone, but I almost want to embrace it now. The curtains are supposed to create the atmosphere of being a bit lost in a maze, you can sort of see where you’re heading, but not quite, just as things in life tend to go. And also represent a certain anxiety. I like those individual ‘chambers’ for the works, and how you can never really see the whole picture, so the story sort of unravels itself slowly, and so on. I’m very pleased with how the curtains turned out, actually!

MA: Figurative painting with hints of symbolism is on the rise again, and your work reflects that as well. How did you find your style as a painter?

AM: I guess Tartu University Art Department really created the basis for figure painting. For a short while afterwards, I wanted to distance myself from figurative painting and do something different, but somehow it didn’t work out. In a way, I find abstract painting a lot harder than figurative: there’s so much awful abstract art out there, even more so than figurative, I’d say. How to make it work and have a similar sort of inner life is tricky. I do like a lot of abstract painters though (one is mentioned above). But the exact visual language, I’m not sure. I’m a classic dumb artist unable to say much that is wise and interesting about my work.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

MA: You have been living in London for the past ten years. How do you compare the UK and Baltic art scenes?

AM: It’s over ten years I’ve been here now. It’s very hard to compare. Also, I follow the Baltic art scene far less. Sometimes it seems to me it’s more vibrant and experimental than the UK, and vice versa. When it comes to painting though, I love the scene here; but again, I don’t know much about the rest of the Baltic besides Estonia, where I feel that figurative painting like mine is a rarity.

The UK art scene has so much more money, both in private galleries and in institutions. Seeing the commercial art world from this side has also been fascinating.

It’s much easier to get your work out there in the Baltic, in a way, though, it seems. Big fish, small pond; small fish, big pond; yada yada problems.

MA: Who are you following, and who do you find interesting, on the UK and the Baltic art scenes, either among contemporary or historic artists?

AM: In terms of painters, in Estonia, my all-time fave is Peeter Mudist. On the UK scene, I’m a sucker for Francis Bacon. I’ve stated several times that there can never be a better painter, though I don’t always stand by this by all means. Of contemporary living artists whose work I follow and like, I can’t draw UK/Baltic lines, as it’s much broader: Hamishi Farah, Naudline Pierre (obsessed!), Albert Oehlen, Peter Doig, Oscar Murillo, Tal R.

Angela Maasalu, ‘A Fool with a Heart of Glass’, exhibition view, Tartu Art House, 2023. Photo: Anu Vahtra

MA: You are interested in psychoanalysis and dreams, and it shows in your paintings. Can you elaborate on that interest a bit?

AM: I wish I was actually more knowledgeable about it, ha ha. Then I would, yes. I see my Jungian analyst twice a week, and our conversations feed into my work.

MA: You are also an avid reader. Can you name three books and authors that have influenced you the most?

AM: Thomas Bernhard (everything), Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, Margaret Atwood’s Cats Eye.

MA: In your works you reflect on many of the problems of modern life, such as the constant lack of time, anxiety, and mental health issues. How do you see the world today and our future on Earth? Ha ha, a simple little question …

AM: Ha ha, a tiny question … Something needs to radically shift and change in general. Not sure how … Despite how negative I seem to be, I don’t think it’s all that hopeless. Or if it is then f**k it. It is what it is … it doesn’t sadden or depress me.

MA: What are you working on now?

AM: Oh, I’ve started lots of things! It’s all shifting a bit in terms of the visuals, though. I think about colour and form more than a theme: that’ll come later anyway as I’m working on something. Kind of trying to be even more intuitive and less intentional, I guess.

Artist Angela Maasalu and curator Maria Arusoo. Photo by Jürgen Vainola

***

Angela Maasalu’s paintings focus on personal and intimate themes. She is interested in contradictory human experiences, recognising simultaneously happiness and sadness, and the drama and comedy of life. She often uses autobiographical elements to tell stories, combining them with symbolic and poetic imagery in order to expand her personal experience to a more widely understood level. Her work is metaphorical, fairy tale-like, and relies on narrative beyond the image.

Angela Maasalu lives and works in London. She studied painting and art history at the University of Tartu (BA, 2012), and painting at the Estonian Academy of Art (MA, 2015), and at UAL Central St Martins in the UK (2013–2014). In 2017 and 2019, Maasalu was nominated for the AkzoNobel Art Prize (formerly the Sadolin Art Prize). She has had solo exhibitions in Tallinn, London, and Irákleios in Greece.