We live in the string theory and God particle age, when everything seems equally feasible, and yet somehow even more improbable. It is estimated that about 7 per cent of all people who ever lived are currently alive, but ironically researchers speak about a budding pandemic of loneliness.

The phenomenon called sonder, i.e. the sudden realisation that every random passer-by is living a life as vivid and complex as your own, coexists with ideas of extreme egocentrism. Everyone wants to understand each other until their opinions stop aligning. Different opinions should not necessarily mean conflict, provided that people are accepting of others’ separate realities.

Splintered Realities is the title of this year’s RIXC Art and Science Festival and exhibition, which aims to analyse how members of modern society tend to live in separate information bubbles, like echo chambers, each a master of their own reality. The exhibition at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre features artworks by international artists who explore the challenges of our contemporary condition: ubiquitous media, pandemic concerns, and social divides, which, affected moreover by an ongoing war, have landed us in a world of splintered realities.

Some philosophers claim that the invention of writing gave grounds to the precursors of modern warfare. Writing probably began at the same time that early civilisations broke out of hunter-gatherer societies as a mechanism to record the new idea of ‘property’, such as livestock, grain supplies or land, which is never enough. It allowed the earliest governments to enlist its people for military service by inviting them from the furthest corners of the country. Some go as far as to claim that ‘The total wars of our time have been the result of a series of intellectual mistakes …’ (Professor J.U. Nef). These days the field of modern information warfare usually stretches out through comment sections, public chat rooms, meme pages on social networks, audio interface of online video games, and many more platforms. The absurdity of ferocious online debates has even had new terms invented for it. Godwin’s Law is based on a saying coined by Mike Godwin that goes: ‘As a discussion on the Internet grows longer, the likelihood of a person/s being compared to Hitler or another Nazi increases.’

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

The video piece Radicalization Pipeline by Theo Triantafyllidis shows how blurred the line is between fact and fiction. Oddballs with Kekistan flags, furries, antifas and magical creatures form a ragtag bunch of misfits who seemingly aimlessly fight each other in the RPG-inspired battle royale field, a scene very reminiscent of the white supremacist rally that took place in Charlottesville in 2017, various alt-right and antifa clashes in recent years, and the 6 January attack on the US Capitol (real life events greatly influenced by niche online communities). Someone even joked on the Internet that: ‘Fox News did to our parents what they said videogames would do to us.’ But not only people get radicalised: technology itself is not immune to it. In 2016 it took less than 24 hours for Twitter users to corrupt an innocent AI chatbot called Tay. After it was launched, people started tweeting the bot with all sorts of offensive misogynistic, homophobic, racist and anti-Semitic remarks. And soon afterwards, Tay started repeating these sentiments back to users. AI currently only parrots our failings and our ignorant misconceptions. It is much more unnerving to think about a future when AI finally surpasses us in all fields of life, and judges us for our imperfect design.

The artists Laurent Mignonneau and Christa Sommerer bring the viewer face to face with their own vanity and self-admiration in the interactive computer-based installation Portrait on the Fly. This mirror, consisting of a swarm of flies, imaginatively propels its viewer forwards into a seemingly infinite progression of possible representations of the self that is ignited by the insatiable human fascination of seeing your own reflection, while simultaneously pulling them away because of the instinctive revulsion against insects. The selfie, a perceived symbol of contemporary narcissism, is aggressively pushing to expand its boundaries beyond pictures and drawings, once reaching the flies at the risk of entering the excreta zone.

Formerly the luxury of only a privileged few, portraiture is now readily available to everyone: we are almost force-fed this constant barrage of faces through social media feeding tubes. An individualist collective becomes numb to originality and jeopardises the idea of being your true self. More recently, BeReal, a French app that tried to start a trend in more honest and authentic social media engagement by encouraging users to share a photograph of themselves and their immediate surroundings given a randomly selected two-minute window every day, experienced the inevitable implosion on itself. Users started to retake pictures at more convenient times, asking others to hold the phone so that they could pose, thus destroying the entire concept of showing your real life. What was supposed to bring in a new, psychologically healthier social media became just another of the uninspiring ‘engineering your public persona’ apps.

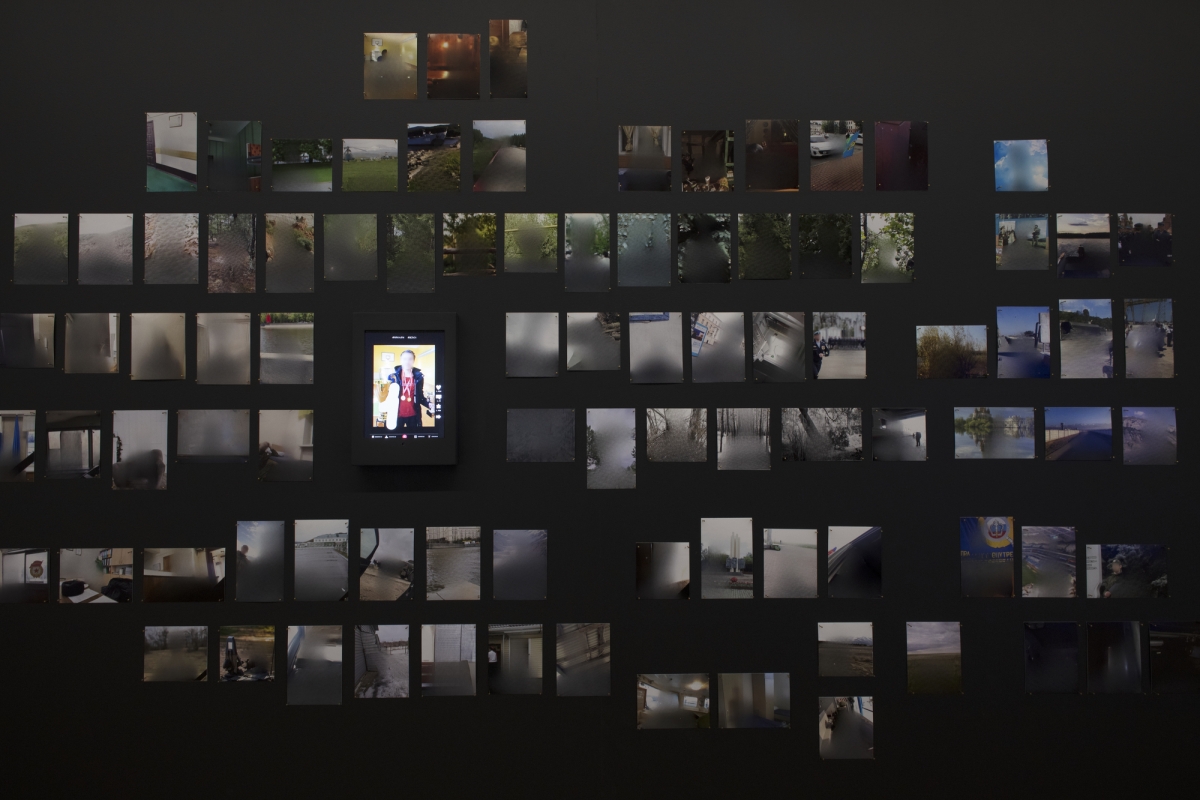

Net citizens have been cringing and collecting bizarre selfies from East European (and especially Russian) sites for years. A certain bombastic Slavic aesthetic is kitschy and ridiculous, yet you cannot take your eyes off it. In his installation Alternative Realities, Jurģis Peters shows perhaps much more modest, but significantly more threatening, found images of fallen soldiers in the Russian army. Many of them pose nonchalantly on duty, proudly showing their military uniforms and guns, completely ignorant of the geopolitical situation and basic human decency. Replicating the initial Russian government denial that its soldiers had seized government buildings and other strategic facilities in Crimea in 2014, the artist creates an alternative reality in which recently fallen Russian soldiers never even existed, a similar narrative the Russian government tries to perpetuate to hide the true size of its casualties. People exposed to disinformation start to lose touch with reality, then unconsciously inhabit a new realm based on lies. New generated images showing soldier-free scenes betray a process of dehumanisation summoned by the unsophisticated warfare strategies and accelerated by emerging technologies.

The short experimental film All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace / Deeper Meditations #1-#6 by the Turkish artist Memo Akten contemplates the possibility of an imaginative exchange between artificial intelligence and the human consciousness. Is it possible that a positive symbiotic relationship between man and machines can counteract all the negatives of the digital era, the so-called Second Machine Age? Dall-E, Dream by Wombo and other user-friendly AI systems that can create realistic images and art from a description still use images on the Internet as the basis for their renderings, so for now it is just a cunning way to get round copyright laws. By using his own portrait as the basis for the seamless AI-generated loop, the artist protects himself by using one thing that is still our indisputable (?) property, our biometrics. According to the law, AI cannot be considered an author, hence consolidating the ideas in the essay ‘The Death of the Author’ by the French literary critic and theorist Roland Barthes. Is the death of the author the birth of machine absolutism?

We could imagine an exhibition where one part of the gallery exhibits the creations of a real artist, and another part shows works by an artificial intelligence substitute, using the artist’s style. Would there really be any recognisable difference between the two different forms of creation? And who could take the credit for this kind of exhibition, the artist, AI or the scientists who created the technology allowing it to happen? Perhaps the most deserving of accolades would be the public who agreed to play this copyright charade, since because AI is still in its developmental stage, audiences must willingly suspend their disbelief, and see machine learning, statistical models and algorithms as something more sophisticated.

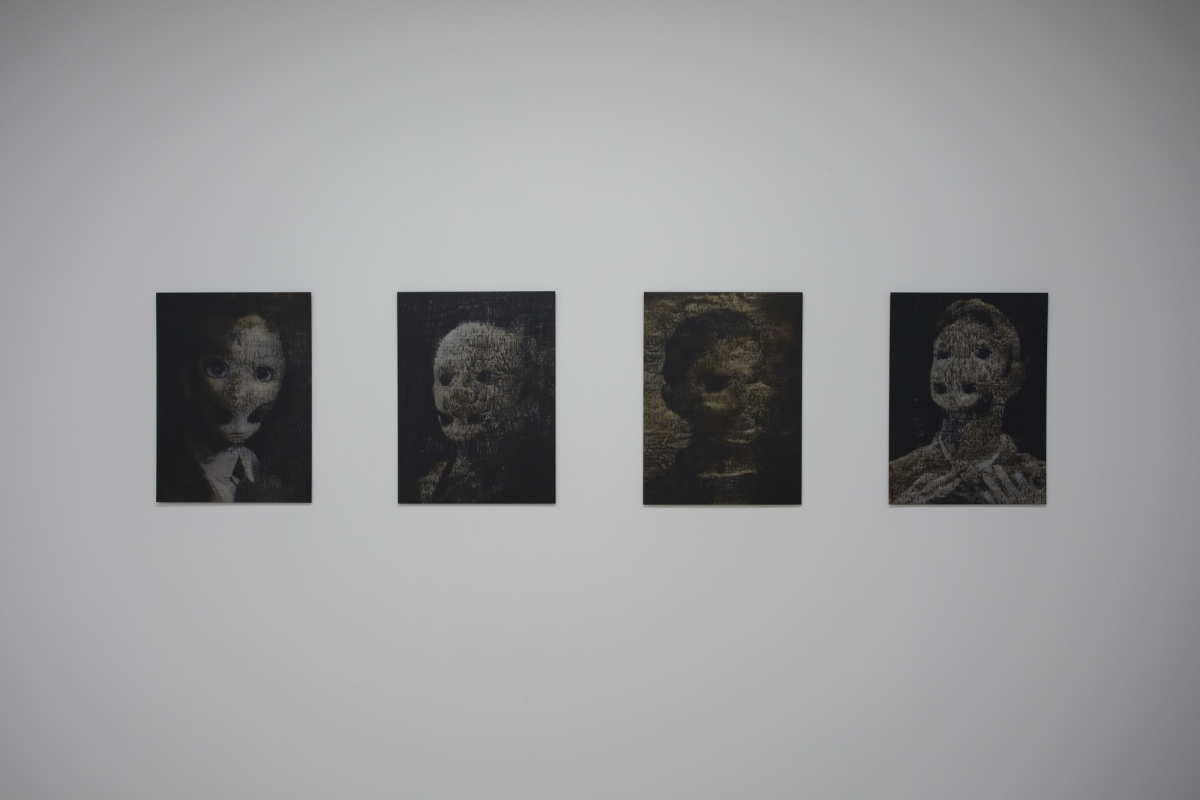

The digital drawing triptych Grey Gold, Black Lakes, White Latex by the Latvian artist Sabīne Šnē showcases intriguing ideas about technologies as extensions of the Earth. And although it is seemingly impossible to separate humanity’s evolution from technological advances, technology also often masks our fragility and our fear of extinction. The series Neural Decay by the German artist and neurographer Mario Klingemann contains unique prints generated by custom-trained generative adversarial networks. This is what artificial intelligence’s memory of the human race might look like once we are gone. But for now, we treat AI as a sort of oracle or fortune-telling tool: there’s a trend on social media to use text-to-image AI generators to answer questions like ‘Who rules the world?’, ‘What will the end of the world look like?’, etc. It demonstrates that we tend to put an aura of mysticism around something we do not fully understand. AI cannot know more than we do, yet we still seek to capture the wizard behind the curtain, knowing full well that it is just an incarnation of our own collective dreams and fears. Voltaire was not exaggerating when he said: ‘If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him’.

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

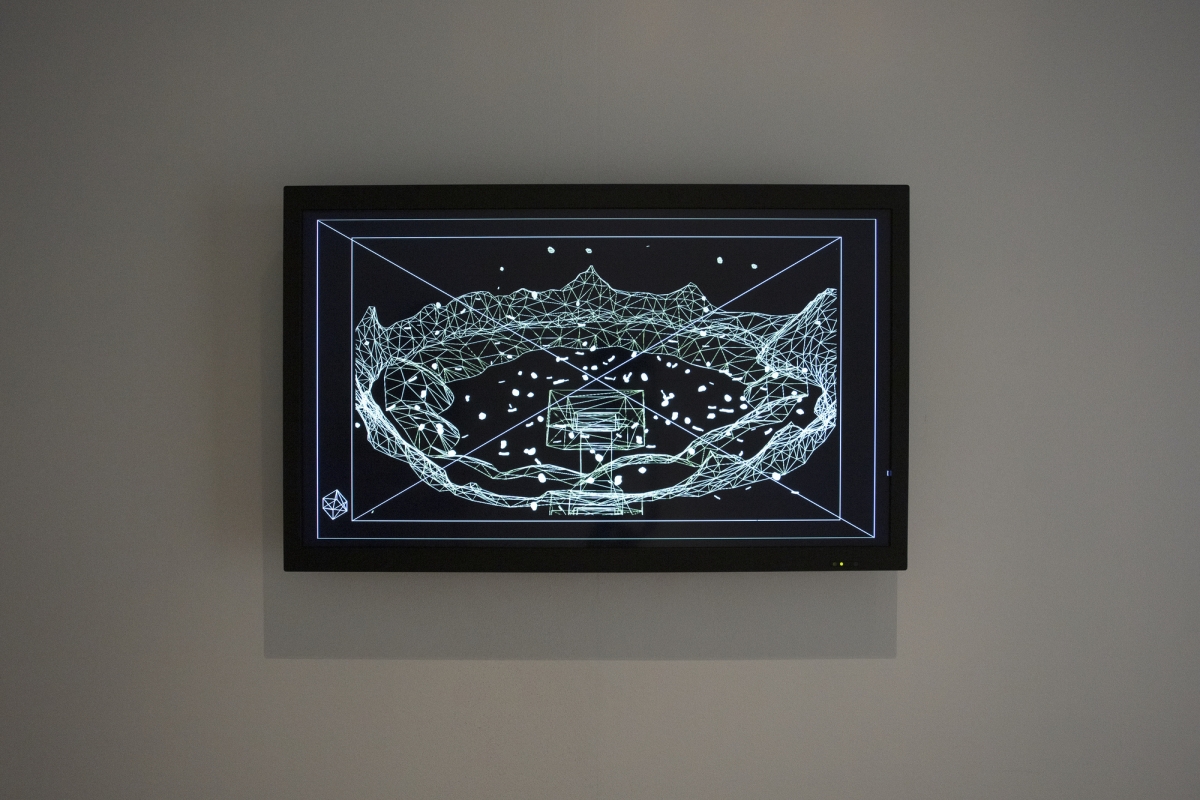

The interactive AI simulation program finalforest.exe by the Indian artist Sahej Rahal listens closely and reacts to the outside world. We see a creature wandering about a virtual habitat. One can even interact with it through a microphone. Audio feedback then interferes with the movements of the strange beast, and it emits a burst of molten black petro-structures. This personification of environmental guilt, presented in a playful way, awakens a subconscious mythical thinking that intensifies the fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the impact of climate change and associated concerns for the future. How should humanity justify its carbon footprint? Are there any appropriate justifications?

While PBJ’s Bug Out Bag by the USA-based artist Allison Stewart shows what is inside the escape bags of various people around the world, the Latvian artist Alvis Misjuns provides a different kind of virtual escape. The sculpture and WebVR multiuser experience Piece on Web offers a shelter from scammy online ads, clickbaity articles, duplicitous influencers, and annoying trolls. An unusual twist in this new-found refuge is that every participant is provided with an avatar of an inanimate object, for example, a twig, rock, leaf or something else common to a desert. To morph into a giant bug and scare your well-meaning family is not enough: modern problems require modern solutions. The answer to intrusive corporate metaverse campaigns can be choosing to be off-the-grid, reduced to a disembodied rock in the wasteland with no means of communication with the outside world. It seems like a perfect illustration of the term coined by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant ‘thing-in-itself’ (an object as it is, independent of observation).

The video piece 489 Years by Hayoun Kwon recreates the personal memories of a soldier visiting the Korean Demilitarised Zone between North Korea and South Korea. Ironically, demilitarised zones are usually much more prepared for war than for peace. According to specialists, there are 2.3 landmines for every square metre of land in Korea, and it will take 489 years to remove all the mines in Korea, including those in unidentified places. The narrator goes 30 years back in time, but for this place that is stuck in time, exact dates are probably irrelevant. The most vivid memory of the storyteller is perhaps an image of the rare flower and the mine: nature’s beauty coexisting with the innate ugliness of human nature. A similar motif of liminal spaces is also analysed in the installation AION by Jacob Kirkegaard and the virtual reality game Void by Debbie Ding / DBBD.SG. Growth and decay, so normal in nature, bewilder us in urban environments. They immediately remind us of our own mortality and our futile attempts at leaving a mark on the world.

‘Go touch some grass’ is a popular online insult, and an alternative way of telling someone to literally ‘go outside’, implying they are spending too much time on the Internet and losing touch with reality, thus affecting their well-being, judgement and quality of life in general. Grass, as a symbol of simplicity and togetherness, is well liked by many poets, and transcends time. Walt Whitman’s famous, and controversial at the time of its publication, collection of poems Leaves of Grass contains the poem ‘Eidolons’, pertaining to many similar themes touched on in this exhibition. The poem ends with these lines: ‘The noiseless myriads, / The infinite oceans where the rivers empty, / The separate countless free identities, like eyesight, / The true realities, eidolons.’ It observes a world beyond our immediate perception and our mind’s comprehension. We cannot claim that our reality is the only righteous one, superior to the experiences of others, because our vision is incomplete and imperfect. Whitman is also not necessarily saying that science is the wrong tool to assess the megaverse and all its glory, just that it only gives us part of the picture. The missing pieces can be filled in by artists, who are constantly issuing eidolons, representations of various ideas.

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere

RIXC Art Science Festival exhibition ‘Splintered Realities’ at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Kristine Madjere